Hunky Shaw

Hunky Shaw’s major-league career consisted of one at-bat with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1908. Though barely a blip on the national radar, his accomplishments in the minor leagues of the Pacific Northwest made him a local legend. He won the Pacific Coast League batting title in 1910 and helped bring professional baseball to Yakima, Washington, in 1937. His peers remembered him as a “pugnacious leadoff batter who would do practically anything to get on base.”1

Hunky Shaw’s major-league career consisted of one at-bat with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1908. Though barely a blip on the national radar, his accomplishments in the minor leagues of the Pacific Northwest made him a local legend. He won the Pacific Coast League batting title in 1910 and helped bring professional baseball to Yakima, Washington, in 1937. His peers remembered him as a “pugnacious leadoff batter who would do practically anything to get on base.”1

Royal N. “Hunky” Shaw was born on September 29, 1884, in Yakima. He was the second of five children born to Andrew Jackson “A.J.” and Alice (Hawkins) Shaw, a pair of Oregon natives. A.J., along with his father and brothers, were some of the early pioneers who took up homesteads in central Washington’s Yakima Valley. The region’s ideal conditions for agriculture and its location on the Northern Pacific Railroad would spur Yakima’s growth in the early 20th century. “I was fortunate to live and grow up in the beautiful spot where the two forks to the Ahtanum Creek united,” Shaw once said. “I was a poor boy, barefooted, with a willow pole, a string line, and a bent pin for a hook and a grasshopper for a lure.”2 A.J. co-owned a funeral business called Shaw and Flint, also known as the Yakima Furniture Company and later Shaw and Sons. He also served stints as county sheriff and mayor.

Royal attended North Yakima High School, where he played halfback and captained the football team. His graduating class comprised 15 students – seven boys and eight girls.3 In 1903, the 18-year-old played left field for the Yakima Hop Pickers, a semipro team. He impressed enough that Blair Business College in Spokane offered him free tuition if he would play for the school’s baseball club.4 After graduating in the spring of 1904, Shaw left Yakima to join the Roseburg Shamrocks of the Oregon State League. That fall, he enrolled at the University of Washington to study pre-law.

Shaw, who was 5-foot-8 and 165 pounds, played halfback for the Huskies football team and third base for the baseball squad. The blond-haired youngster with a stocky build was given the moniker “Hunky” by Washington’s quarterback, Dode Brinker.5 In one gridiron contest between the Huskies and the University of Idaho, Shaw ran back a kickoff 105 yards for the game-winning touchdown.6

In January 1906, Shaw left the university to become a partner in the funeral parlor business with his father and brother.7 Though this may have been his intention, baseball was Hunky Shaw’s calling card. That spring he was the captain and third baseman for the North Yakima Tigers, an amateur club. By May, he had signed with the Tacoma Tigers of the Class-B Northwestern League. In 83 games with Tacoma, he batted .276.

Shaw returned to the Tacoma Tigers in 1907 and hit .278 with seven homers in 150 games. “Hunky Shaw, the scrappy third baseman, is not only a sweet hitter, but the fastest man in the league on his feet, and he can either drive the ball out on a line or lay it down in front of the plate,” reported the Seattle Daily Times.8 Despite playing in the remote Pacific Northwest, major-league teams had discovered the talented young third baseman. Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack offered Tacoma $1,000 for Shaw in June, but team president George Shreeder declined.9 On August 8, it was reported that the Pirates offered Tacoma $1,500 for Shaw’s services and wanted him to report at once.10 Shreeder again rebuffed the offer, opting to keep his speedster for a shot at the pennant. A few days later, he agreed to sell Shaw to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association for $1,000 with an agreement that Shaw would finish the year with Tacoma.11 In September, the Pirates got Shaw after all when the organization exercised its authority to draft him from St. Paul, getting him for $500 less than their original offer.

Shaw spent the winter honing his skills playing winter ball with a Southern California club called the San Diego Ralstons. He showed off his speed in a field day competition by winning a beat-out-a-bunt contest with a time of 3.02; he also circled the bases in 15 seconds.12 On February 28, 1908, Shaw signed a contract with the Pirates for the upcoming season.13 In March, he traveled east to the Pirates’ training camps, first in West Baden Springs, Indiana, and then Hot Springs, Arkansas.

The Pirates had an opening at third base, at least temporarily, heading into the 1908 season. Their returning third sacker, Alan Storke, was attending Harvard Law School during the offseason and received permission from the club to report in June. Shaw was considered a leading candidate to fill in. Some reporters were so impressed by Shaw’s nifty fielding early on they thought he might take Storke’s job on a permanent basis. “Shaw has been pulling off some sensational fielding stunts during every day of practice. He handles ground balls neatly, is quick and accurate in his throwing and can deliver the ball from any position,” wrote one scribe.14 However, Shaw’s bat failed to impress, and he was relegated to the bench to start the ’08 campaign. Tommy Leach, the Bucs’ former third baseman-turned-outfielder, returned to the hot corner.

After failing to see any action during the Pirates’ first 20 games, Shaw finally got his chance on May 16. Pittsburgh hosted the Philadelphia Phillies at Exposition Park in front of 3,050 spectators. The Phillies scored four runs in the first three frames off Pirates starter Sam Leever. When Leever’s spot in the order came up in the bottom of the third, player-manager Fred Clarke called on Shaw to pinch-hit. Facing Phillies righty Lew Moren in what would be his only major-league at-bat, Shaw struck out. He became the second player born in Washington state to appear in the majors; Jack Bliss, a catcher with the Cardinals who hailed from Vancouver, had debuted only six days earlier.

By June, Shaw had been farmed out to the McKeesport (Pennsylvania) Tubers in the Ohio-Pennsylvania League. In July, McKeesport sent Shaw back to Pittsburgh, who then sold him to the Jersey City Skeeters of the Class-A Eastern League for $500.15 In 59 games with Jersey City, he hit .236 with two home runs. He was repurchased by Pittsburgh in late August but did not appear in another game.

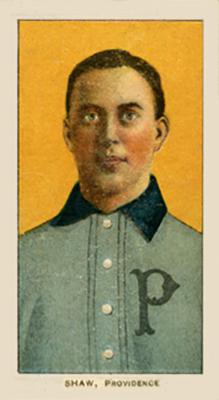

Shaw returned to Washington following the season and then spent another winter playing ball in the sunshine of Southern California. The Northwestern League’s Portland Colts attempted to acquire Shaw for the 1909 season, but no deal came to fruition. Instead, the Pirates released him to the Providence Grays of the Eastern League. For the Grays, managed by future Hall of Famer Hugh Duffy, Shaw played in 30 games and hit .250. He was then sent to the Worcester Busters of the Class-B New England League, playing under another future Cooperstown inductee, Jesse Burkett. Shaw fared much better, leading the league with a .321 average in 89 games while helping Worcester to the pennant.16 In September, he was drafted by the White Sox with a chance to return to the majors in 1910.

Shaw spent spring training with the White Sox before owner Charles Comiskey sold him to the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League for $750 in early April.17 Shaw played in 155 of the Seals’ 210 games, and his .281 batting average led the pitching-dominant league.18 When he received a contract from the Seals for the 1911 season, he returned it unsigned and replied that he could make more money working as an undertaker with the family business. He spent a month coaching baseball at Whitman College and then played first base for Walla Walla of the Blue Mountain League until he was suspended for deliberately spiking another player.19 Shaw and the Seals finally agreed to terms in May. The 26-year-old Shaw hit .252 in 120 games. One of his teammates was a young Buck Weaver.

On July 3, 1911, Shaw married Ruth Cason of Fresno in a unique “double wedding” in which Ruth’s mother also tied the knot.20 The union between Hunky and Ruth would ultimately end in divorce seven years later.

Shaw’s tenure with the Seals ended in September when he was suspended for “indifferent playing.”21 While specifics of this vague claim were not reported, the Seattle Daily Times later described a pair of incidents which may have contributed to Shaw’s eventual dismissal. In one extra-inning game against Portland, Shaw was at second base. Portland infielder Ivan Olson hid the ball in his jersey and then tagged Shaw out when he stepped off the base. The following day, Shaw was manning the keystone and Olson attempted a steal of third. The play was close, and Olson was ruled safe. Shaw spiked the ball into the ground in anger, which allowed Olson to score. Shaw was fined $50 for each play.22 Another scribe later wrote that Shaw was “one of the poorest hands at fielding ground balls that the coast league had ever seen,” including one contest against the White Sox in which three grounders rolled through his legs.23

After his suspension by the Seals, Shaw resurfaced with a semipro club in Richmond, California, and took an offseason job working in oil wells near San Francisco for two dollars a day.24 On December 17, the Seals traded Shaw to the Spokane Indians of the Northwestern League in exchange for 18-year-old Earl Sheely. Of interest, Sheely, whose 24-year professional baseball career included nine seasons in the majors, would not suit up for the Seals until 18 years later. Shaw, who clearly did not see eye-to-eye with the Seals’ brass, welcomed the change, as did the Spokane faithful, who were said to have welcomed the news of his acquisition with “keen pleasure.”25

Hunky spent a few weeks that winter in Yakima getting in shape by playing handball before reporting to Indians spring practice in Walla Walla. He opened the season as Spokane’s third baseman and spent time umpiring local youth league games. During a 40-minute pep talk to the youngsters, Shaw encouraged “clean sport, good habits, and no cigarette smoking.”26 When Shaw failed to produce adequately at the plate, hitting below .200, Spokane president Joe Cohn shipped him to the rival Seattle Giants.27 After the change in scenery, Shaw found his stroke. On June 17, he delivered a bases-loaded hit in the bottom of the 11th inning to defeat his former Spokane mates.28 Serving as Seattle’s leadoff man, the scrappy infielder was known for placing his arm into the path of an inside pitch to draw a base. Years later, some would claim he averaged one hit-by-pitch per game.29 Shaw’s arrival in Seattle coincided with the Giants’ rise in the standings to the eventual league pennant. In 610 at-bats, he hit .284 and stole 37 bases.30

Shaw re-signed with Seattle for the 1913 season. He manned the hot corner in a preseason exhibition against Rube Foster’s American Giants, the most successful Negro League team of that era. Foster’s men hit the ball so hard, “they had Hunky Shaw ducking to save his life,” wrote the Seattle Daily Times.31 As of early June, Shaw led Seattle with a .283 average.32 By September, his average had dipped to .257.33 After a fight with teammate Roy Brown, both players were released.

Shaw spent the offseason back in Richmond, California managing Standard Oil’s semipro club. He signed a contract with the Vancouver Beavers, his fourth Northwestern League team, for the 1914 campaign. The versatile veteran split time between the infield and outfield and hit .244 with one home run in 537 at-bats. Off the field, Shaw made headlines when he filed a lawsuit against the Recreation Park Association, owners of the San Francisco Seals. He sought $214.35 in lost wages from his suspension at the end of the 1911 season and contended that the Seals prevented him from signing with another PCL team by suspending rather than releasing him.34 The case was heard in Portland and resulted in a mistrial after jurors failed to agree on a verdict. Shaw filed a second suit against the Seals seeking $4,000 in damages. Another trial took place in the winter of 1915, and Shaw lost the case.

Vancouver traded Shaw to the Victoria Maple Leafs in exchange for pitcher Walter Smith prior to the 1915 season.35 Midway through the season he was released by Victoria and signed with his former team, the Seattle Giants. He hit .292 for the season in 510 at-bats. During his tenure with Victoria, Shaw demonstrated a fiery temper in a May 31 doubleheader at Seattle. In the first game, Shaw engaged in a verbal back-and-forth with fans in the bleachers. In the second game, he missed a foul ball and received more taunts from the Seattle fans. He responded by firing a ball into the left-field bleachers.36 Shaw was fined $5 and ejected on the spot and then fined another $25 by the league president. To make matters worse, he was sued for $1,000 by a man whose thumb was fractured by the projectile.37 The case went to court that fall, and Shaw was forced to pay the injured spectator $200.38

Shaw returned to the Giants in 1916, playing primarily outfield, and saw a fall in production with a batting average of only .243. After the season, he had a job working at a Seattle-area ice skating rink called The Arena. Other odd jobs he took during the course of his career included painter, plumber, carpenter, and dogcatcher.39 Shaw asked for and was granted his release from the Giants in 1917. He went back to work with Standard Oil in the Bay Area and continued to play for the company’s semipro outfit. His name appears in box scores of the Modesto Elks, another semipro club, in 1919.

In 1920, Shaw signed with the Class-B Yakima Indians of the Pacific International League, later known as the Western International League. In June, he jumped to the Edmonton Eskimos of the Class-D Western Canada League. “He has slowed down considerably since his major league days, but he is still a .300 hitter and should be a big help to the Esks,” wrote the Edmonton Journal.40 Despite losing a step, the 35-year-old managed 16 steals while batting .237 in 55 games.41

Shaw was hired to coach the University of Washington’s freshman baseball team in 1922 and then served as player-manager for Bellingham’s Knights of Columbus team that summer. The well-traveled Shaw proved he had not lost his tenacity in one contest versus the Elks in which he kicked an umpire in anger.42

In 1923, Shaw had short stints playing for the Fairbury Jeffersons and Beatrice Blues of the Class-D Nebraska State League. When another league team, the Hastings Cubs, had a managerial vacancy, Shaw asked for his release from Beatrice and got the job. In May 1924, he was hired as player-manager of the Emporia (Kansas) Traders, another Southwestern League outfit. He led the club out of the cellar but after the team hit a losing skid in early August, fans called for his dismissal, and the club obliged. As a player, Shaw produced numbers that defied his 39 years, hitting .302 in 121 games.

On November 5, 1924, Shaw married the former Clara Waltsberger. The following year he was a player-manager for the Miami Miners in the Class-D Arizona State League. In 1926, Shaw opened up a bicycle and sporting goods store in Yakima.

For the next decade Shaw worked for a pair of independent league teams, first as field manager for the Yakima Bears and then as business manager for the Yakima Indians. During that time, he and Clara welcomed their first and only child, a son named Kenneth.

In 1937, Shaw spearheaded Yakima’s entry into the newly formed, six-team Class-B Western International League. A committee which included Shaw chose the team name “Pippins” (for the apple variety – Yakima County is known for its apple orchards). Some 1,200 fans had submitted suggestions as part of a contest.43 Shaw served as both an executive and field manager in the Pippins inaugural season and then later as a scout. He was also elected the league’s vice president. Like many minor leagues, the WIL disbanded during World War II and resumed play in 1946. Shaw was part of an ownership group that purchased the Wenatchee Chiefs, another WIL franchise, in 1948. He sold his shares a few years later.

When not spending time at a ballpark, Shaw enjoyed hunting and fishing. He was such a skilled fisherman that some called him the “King of the Naches River.”44 He retired from the sporting goods business in 1953 but did not give up work completely. In 1955, at age 70, Shaw became business manager of the Yakima Bears, a charter member of the Class-B Northwest League.

Even at his advanced age, he continued to play in old-timers’ games. The Seattle Daily Times noted that Shaw, playing third base, “fielded a grounder with youthful ease, but bursitis has taken a little away from the throwing arm.”45 The following year, in a pinch-hitting appearance, Shaw was transported to home plate in a wheelbarrow and then promptly scorched a line drive single over third base.46 He continued to participate in old-timers’ games at late as 1961, when he was 76.

Hunky Shaw remained a fixture at baseball fields in central Washington well into his eighties. He died at age 85 on July 3, 1969 in Yakima and is buried at Terrace Heights Memorial Park in Yakima.

In 2013, the Yakima Valley Pippins, a collegiate wood bat baseball team, were founded. The following year, the team honored Shaw, the city’s first major-leaguer and man who helped bring professional baseball to town, by naming their team store after him.47

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Jeff Findley.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com, ancestry.com, and newspapers.com.

Notes

1 “Old-Time Sports Figure Dies at 85,” Spokane Chronicle, July 12, 1969: 10.

2 “Old-Time Sports Figure Dies at 85.”

3 “Commencment (sic) Exercises of North Yakima High School,” Yakima Herald, June 8, 1904: 6.

4 Yakima Herald, April 22, 1903: 10.

5 “Gained First Glory When He Defeated Idaho Eleven,” Idaho Statesman, June 29, 1913: 8.

6 “Spokane Fans Welcome Shaw,” Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington), December 29, 1911: 15.

7 “Local Notes,” Yakima Herald, January 31, 1906: 2.

8 “Gossip About the Players,” Seattle Daily Times, May 21, 1907: 13.

9 “This is Connie Mack, Who Wants ‘Hunky’ Shaw,” Seattle Daily Times, June 25, 1907: 11.

10 “Gossip About the Players,” Seattle Daily Times, August 8, 1907: 13.

11 “Gossip About the Players,” Seattle Daily Times, August 11, 1907: 16.

12 “Young Pitcher for the Tigers,” Tacoma Daily Ledger, December 6, 1907: 9.

13 “Contract Received from Third Baseman,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, February 29, 1908: 12.

14 “Pittsburgh Baseball Club at Last Reaches Hot Springs Training Camp,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, March 22, 1908: 13.

15 “Options,” Cincinnati Inquirer, August 23, 1908: 10.

16 “Shaw Goes to Big League,” Yakima Herald, September 15, 1909: 2.

17 “Report of Commission on Drake’s Case; Detroit’s Claims to the Player,” Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, August 11, 1910: 12.

18 “Seals Lead in Team Stickwork for 1910,” San Francisco Call, November 27, 1910: 50.

19 “Shaw Suspended by President Frazier,” East Oregonian, May 5, 1911: 1.

20 “Daughter and Her Parent Take Vows,” San Francisco Call, July 4, 1911: 2.

21 A.T. Baum, “Hunky Shaw is Suspended for Indifferent Playing,” San Francisco Examiner, September 25, 1911: 13.

22 “Some Yarns in Which Boys of Series Figure,” Seattle Daily Times, October 12, 1916: 20.

23 “Indians Played Football, Noted Historian Says,” Minneapolis Tribune, February 27, 1916: 64.

24 “Shaw Working in Oil Wells,” Spokesman-Review, January 6, 1912: 15.

25 “Spokane Fans Welcome Shaw.”

26 “Grade Leaguers Off Today for Eighth Annual Championship,” Spokesman-Review, April 13, 1912: 15.

27 “Indians Will Play Last Games of Season Here with Tacoma,” Spokesman-Review, September 12, 1912: 17.

28 “Hunky Shaw Hits in Pinch Winning Game for Seattle,” Seattle Daily Times, June 18, 1912: 16.

29 “Old-Time Sports Figure Dies at 85.”

30 “Harry Leek Real Leader League Heavy Hitters,” Victoria Daily Times, October 2, 1912: 6.

31 “Baseball Briefs,” Seattle Daily Times, April 7, 1913: 12.

32 “Sporting Chatter,” Seattle Star, June 2, 1913: 2.

33 “Hunky Shaw Signed by President Brown,” Daily Province (Vancouver, BC), February 24, 1914: 11.

34 “Base Ball Briefs,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), November 16, 1914: 13.

35 “Hughes Hugh in Sports,” Seattle Daily Times, March 17, 1915: 10.

36 “Shaw was Fined for Beaning Bleacherite,” Victoria Daily Times, June 1, 1915: 9.

37 “Hunky Shaw Sued for $1,000,” Seattle Daily Times, June 5, 1915: 7.

38 “Cost Hunky Shaw $200 to Hit Fan,” Tacoma Daily Ledger, November 5, 1915: 7.

39 “Old-Time Sports Figure Dies at 85.”

40 “Moose Jaw Robin Hoods Here for Four-Game Tilt,” Edmonton Journal, June 10, 1920: 20.

41 “Western Canada League Official Batting Averages,” Edmonton Journal, September 4, 1920: 18.

42 “’Hunky’ Shaw Battles with Umpire Ruth in Local Game; Elks Stop K.C. Win Streak, Bellingham Herald, July 3, 1922: 5.

43 “Gas Leak Dear and Dangerous,” Spokesman-Review, April 23, 1937: 34.

44 Sandy McDonald, “Sandy’s Slants,” Seattle Daily Times, October 11, 1942: 5.

45 Lenny Anderson, “Singleton Seeks No. 16 Tonight; Versatile Verble is Victory Star,” Seattle Daily Times, August 19, 1955: 22.

46 Lenny Anderson, “Sportfolio: Old-Timer’s Turn Back the Clock,” Seattle Daily Times, September 7, 1956: 27.

47 Todd Lyons, “Pippins Honor “Hunky” Shaw, Yakima’s Own ‘Moonlight’ Graham,” 1460ESPNYakima.com, May 28, 2014 (https://1460espnyakima.com/pippins-honor-hunky-shaw-yakimas-own-moonlight-graham/). The name is visible in Internet searches and at the tab at the top of the screen when visiting www.pippinsgear.com.

Full Name

Royal N. Shaw

Born

September 29, 1884 at Yakima, WA (USA)

Died

July 3, 1969 at Yakima, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.