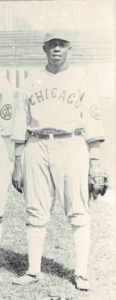

Jack Marshall

Jack “Boss” Marshall stood 5-feet-9 and weighed 167 pounds. He was a right-handed pitcher, both a starter and a reliever. Most of his seven seasons in the Negro National League were with the Chicago American Giants; he appeared on the rosters of the first two teams to win Negro National League pennants. He also played in the NNL for the Detroit Stars and the Kansas City Monarchs.

Jack “Boss” Marshall stood 5-feet-9 and weighed 167 pounds. He was a right-handed pitcher, both a starter and a reliever. Most of his seven seasons in the Negro National League were with the Chicago American Giants; he appeared on the rosters of the first two teams to win Negro National League pennants. He also played in the NNL for the Detroit Stars and the Kansas City Monarchs.

Marshall was born on May 11, 1895, in Carrollton, Missouri, to Sam and Lenora Marshall.1 Sam and Lenora both grew up in the area. According to the 1880 census, Lenora lived with her mother, Rachel, and a sister named Pearlie. Sam lived with his mother, Sarah, and his grandfather, Reuben, who was well-known in the White and Black communities. The local newspaper ran an obituary, rarely seen for Black community members at the time, noting that he had been enslaved by Killus Callaway in Howard County, Missouri.2 Sam and Lenora married on August 7, 1890, when Sam was 27 and Lenora was 22. Their first child, Leota, came in 1891, followed by Jack in 1895. About a week after Jack was born, Sam was working off a $2 fine in nearby Keytesville, Missouri, for drunkenness. In 1900 Sam and Lenora lived with her family with their two children. He worked as a day laborer, and she stayed at home. Sometime after that, Sam left the family, and no further conclusive records could be found about his life. By 1910, the household had moved to Kansas City, Missouri, and everyone lived in Kansas City for the rest of their lives. Marshall’s aunt Pearl was the breadwinner of the family, working as a masseuse throughout her life. His mother Lenora never remarried and occasionally worked as a laundress, maid, or cook to provide supplementary income for the household.

It is unclear exactly when Jack started playing baseball. By 1917, at age 22, he was pitching for Brown’s Tennessee Rats. When he registered for the World War I draft that June, he listed his trade as “minstrel troupe,” working for W.A. Brown in Holden, Missouri, where the Tennessee Rats were based. The group was a combination minstrel show and barnstorming team that toured the Midwest. The players put on comedic-style baseball games during the day, and then they performed shows with singers, musicians, and skits at night.3 One such example of the Rats’ itinerary involved a two-game weekend series against the Brandeis Department Store team. Their appearance on Sunday, July 29, was part of an “athletic carnival” that featured such things as “wrestling, base ball, tug of war, shadow wrestling, and other classy events.”4 Not everyone appreciated such antics, including a South Dakota newspaperman who called a portion of a 1916 game “a vaudeville performance by the visiting negro team that exasperated the Minnesotans, amused the crowds, but included little baseball.”5

On June 11, 1918, Marshall was drafted into the US Army in Kansas City, Missouri. He never left Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, where he worked in the Army Service School there. He was honorably discharged on December 18, 1918, making him available to play the next baseball season.

In 1919 Marshall joined the Chicago Union Giants for the season. That summer came to be called the Red Summer because of the many eruptions of racial violence throughout the United States. These race riots often occurred in industrial cities that had seen a large influx of Black migrants, who had trekked north looking for better work and social conditions than they found in the rural South. Much tension centered on employment and union membership, and strikes across the country contributed to this racial tension.

Like many other cities, Omaha, Nebraska, experienced labor unrest related to a national Teamsters’ Union strike. By the beginning of the summer, “local boilermakers, bricklayers, tailors, telegraphers, teamsters, and truck drivers had already walked off their jobs.”6 On June 21 the Central Labor Union in Omaha threatened to add an additional 30,000 striking workers to the already numerous crowds. In response, the police outlawed public gatherings. Strikebreakers, including “eight Negros from Kansas City,” required the protection of a hastily gathered 150 new police deputies.7 On June 25 the mayor called on the American Legion to do the jobs of the strikers, and they responded by promising that “anything savoring of anarchy in Douglas County shall be put down by the Legion.”8 Many concessions were made to mollify the strikers, and many had returned to work by June 27.9

On June 30, 1919, the Union Giants arrived in Omaha to play the Armours. a company team of White players from the Armour packing plant. During the first game of the doubleheader, a “45-minute riot” broke out. It started originally as a fight between Jimmy Collins and Turner, a first baseman for the Union Giants. When Collins slid into first base, Turner accused Collins of spiking him. Marshall then came in from right field to get involved in the dust-up. He punched Collins above his left eye, causing a wound that needed two stitches. This punch incited the fans, both Black and White, to join the fight, clearing the benches and the stands. Some gathered baseball bats and other impromptu weapons, adding tension to the situation. The police chief, named Eberstein, happened to be at the ball game with his son Russell. He pushed back the gathering mob, waving his gun at the crowd. He arrested Marshall. The fans continued to hurl venom, but the police chief’s action defused further threat of physical violence. More law officers arrived, taking Marshall to jail in handcuffs. The game then continued, and the second game was also played without incident. The Armours swept the doubleheader.10 The next day, Marshall was fined $25 for disturbing the peace and was released from custody.11

On August 3, 1919, the Chicago Union Giants were to play the White Eagles of Gary, Indiana.12 The week before, on July 27, a Black boy floated across an invisible line in the water that separated segregated beaches in Chicago. This began riots marked by murder, arson, and other acts of violence. Chicago Mayor William Hale Thompson requested that the state militia and National Guard be activated, resulting in nearly 10,000 troops pouring into the city; these troops did not leave until August 8.13 The Gary team canceled the game, citing a “considerable sentiment” against the White Eagles playing a Black team given the “seriousness of the Chicago race riot situation.”14 It is unclear whether the players for the Union Giants would have been in Chicago at the time of the riot, but it is unlikely. They played in Omaha on July 27, beating the Armours while Chicago exploded. Omaha had a race riot at the end of September, resulting in the attempted lynching of the mayor and the lynching of Will Brown, a 41-year-old Black packinghouse worker.15

In 1920 the Negro National League was formed by Rube Foster and other Midwestern team owners in Kansas City, Missouri. The league consisted of eight teams and played a 60-game schedule. Foster decided to distribute the star players to different teams. Then there would be some parity among the teams, and each club would have a “draw” so fans would flock to the gates and watch the game. Fans were not thrilled with their favorite players being assigned to other teams but learned to accept it. When it was time for spring training, Foster had several players, including Marshall, show up for tryouts in case the players he had told to report did not arrive at Schorling Park.16

Marshall impressed Foster. He was one of the new players added to the Chicago American Giants roster, joining the club as a pitcher. The team was considered the favorite to win the championship. Foster himself was sure his team would come out on top, stating that there was “no fear of the future of the Giants” and that “ultimate success is sure.”17 The team finished the season in first place with a 43-17-2 record in league play. In 17 games (13 starts), Jack Marshall amassed a 6-7 record in league games with nine complete games and a 3.41 ERA. One of his more impressive wins was a 13-inning, 1-0 shutout on June 3 against the visiting Cuban Stars West. Six days later, he shut out the St. Louis Stars, 6-0, on a three-hitter.

Foster saw enough from Marshall to bring him back for the 1921 season. Star players Bingo DeMoss, Dave Malarcher, and Cristóbal Torriente also returned. In January, Foster took his team to Palm Beach, Florida, where the players worked for the Royal Poinciana Hotel as porters, bellhops, and in other service jobs while playing as a company team for the resort.18 Other Negro League teams also brought players to resorts in the area. Hilldale made up the team for the Breakers Resort. These teams formed the Florida Hotel League, which played from January to early March, allowing the players to earn money while also providing preparation for the Negro National League season.19 After the last game in Florida, the American Giants barnstormed their way to Chicago for the start of the regular season.

The Chicago Defender thought Marshall was a likely candidate to pitch for the American Giants’ on Opening Day, May 7, but the nod went instead to teammate Dave Brown.20 For the 1921 NNL season, Marshall had a 6-4 won-lost record in 14 games (11 starts) with 9 complete games and a little over 91 innings pitched. On June 4 he shut out the Columbus Buckeyes in the first game of a doubleheader on three hits. Malarcher and Torriente scored the only runs for the American Giants in the pitchers’ duel.21 Rube Foster’s trust in his team was well-founded, and the American Giants repeated as Negro National League champions.

The 1922 season brought a change of scenery for Marshall, who was sent to the Detroit Stars. Foster overhauled his pitching staff, acquiring all new pitchers, save for Dave Brown.22 Marshall made his Stars debut on April 16, pitching in relief in a combined five-hit shutout of the Cowpers, a local White amateur team. The Detroit Free Press said that the addition of Marshall and other players had “greatly strengthened the Stars.”23 Marshall pitched respectably for the Stars, ending 1922 with a 6-5 record over 19 games (12 starts), 7 complete games and 112⅔ innings. He also made three appearances for the New York Lincoln Giants after the NNL season and pitched to an 0-1 record.

In 1923 Marshall returned to the Chicago American Giants. The pitching staff was considered “weak,” and it was said that Foster was using “a patchwork of journeymen (some of whom struggled with drinking problems) and ‘flash in the pan’ throwers.”24 Despite winning championships with these types of pitchers, the pitching staff in 1923 found it difficult to achieve success as none of them had the ability to overpower hitters.25 Marshall struggled mightily, appearing in 17 games and posting a 2-6 record.

Marshall looked to rebound in 1924. He went to spring training in Texas with the team, but ended up being left along with fellow pitchers Dicta Johnson, Harry Kenyon, and Fulton Strong.26 He then reported for training with his hometown Kansas City Monarchs.27 However, he pitched in only three games and had an 0-1 record despite posting a 3.45 ERA that was better than the league average (112 ERA+). His last appearance for the team came in a late-May doubleheader against the Indianapolis A.B.C.’s.28

At the beginning of 1925, Marshall was back with the Chicago American Giants, but his second stint with the team was short-lived. Once again, Rube Foster unconditionally released multiple players at the beginning of the season. Marshall was among the group, who also included veterans George “Tubby” Dixon, Tom Williams, and Dick Whitworth. The move was made in accordance with a new rule that “all players held in reserve or upon whose services options are held, must be placed on salaries by clubs holding them on May 1.”29 Marshall did not appear again in any box scores until 1928.

Jack Marshall was living in Kansas City, Missouri, according to a 1924 city directory. On November 15, 1927, he married Helen Hayes Gibbs in Jackson County, Missouri.

In 1928 Marshall returned to the Negro National League for a second stint with the Detroit Stars. Several other former Monarchs were members of the team. Marshall and Rube Currie, George Mitchell, and Grady Orange were said to be responsible for most of the Stars wins through mid-May.30 The recurring message of newspaper accounts of Marshall’s outings was that he was giving up a low number of hits in his outings. He had a career-best 10-5 record 142⅓ innings pitched. On July 28 Marshall gave up five hits and three runs in a 9-3 complete-game win against the St. Louis Stars, the team that went on to win the league championship.31

During Marshall’s second term with the Stars, the city’s underworld was dominated by the Purple Gang, otherwise known as the Sugar House Gang. The gangsters, primarily Jewish, were a known group of bootleggers who “supplied Al Capone with Old Log Cabin, his favorite whiskey.”32 The Purples were also involved in many other “sin industries,” including prostitution, which was rampant in Detroit in the late 1920s because there were so many more men than women living in the city. In 1926 there were 711 brothels operating in the open “within a one-mile radius of City Hall.”33 According to Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Jack Marshall had a brothel in the late 1920s, likely in 1928, the year he played for the Stars. These dealings meant that he would likely have had to have some “understanding” with the Purples. Even so, Radcliffe spoke of run-ins with the police: “[Jack] had a couple of good girls. He was what we called a ‘player.’ It was raided two or three times. I was in it one time, but the policeman recognized me and let me go.”34

Marshall returned once more to the Chicago American Giants in 1929. Showing he still had something left in the tank at age 34, he turned in a solid performance against the St. Louis Stars, one of the best teams in the league after winning the championship the previous year. In the third game of a five-game series, on September 14, he gave up 10 hits and four runs and helped himself at the plate with an RBI base hit in two at-bats. The American Giants won the game, 9-4, taking three of five games in the series.35 After a 4-6 season in 1929, Marshall finished his pitching career with a 34-36 record with 42 complete games and a 4.26 ERA in 108 appearances (77 starts).

In 1930 Marshall reported on the US Census that his occupation was “baseball club.” However, no records were found to show what team he may have played for. Even though he and Helen Gibbs had married in 1927, the couple seems to have parted ways. He was living with his mother, Lenora, Aunt Pearl, and a cousin named James Walker. Meanwhile, Helen was living with her family and working as a maid for a private family. Marshall listed himself as single while Gibbs indicated that she was divorced.

By 1934 Marshall and Helen Gibbs had reconciled and were living with his family at 2726 Woodland Ave. On May 5, 1936, Helen gave birth to daughter Mary Alice in Kansas City; she was the couple’s only child. By 1939, the Marshalls had bought a home at 1914 Montgall Avenue in Kansas City. According to the 1940 census, Marshall worked as a laborer on a sewer project. His World War II draft card from 1942 indicates that the couple may have had another falling-out, since his address is listed on it as 2012 Askew. His mother and aunt still lived on Woodland, so he had not returned to their residence. This new address may also have been related to his work for the WPA, the New Deal employment program.

Marshall eventually settled into a post-baseball career with the Kansas City Department of Public Works. By 1955 he had once more reconciled with Gibbs, and they moved their family into another house they purchased at 2534 Garfield Avenue in Kansas City. However, they later returned to the old neighborhood; at the time of their deaths they were living at 3310 Montgall, about two miles north of their first home. Jack died on his 66th birthday, May 11, 1961, in Wadsworth, Kansas, which is present day Leavenworth. He is buried in the Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Bill Nowlin and Frederick C. Bush for research assistance.

Sources

Unless noted, all statistics come from Seamheads.com, all genealogy information comes from Ancestry.com, and all directory information comes from the Heritage Quest database.

Notes

1 This seems to be the accurate birthdate based on the majority of records, including his military records. The exception that gets cited in other places is from his World War I draft registration card, which lists 1893.

2 Chariton Courier (Keytesville, Missouri), November 23, 1900: 3.

3 Donn Rogosin, Invisible Men: Life in Baseball’s Negro Leagues (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020), 55.

4 “Athletic Carnival When Tennessee Rats Come,” Omaha Daily Bee, July 27, 1917: 7.

5 “Tennessee Rats Win Game 6 to 3 Against Jasper, Minn., Here,” Sioux Falls (South Dakota) Argus-Leader, July 28, 1916: 3.

6 Michael L. Lawson, “Omaha, a City in Ferment: Summer of 1919,” Nebraska History 58 (1977), 395.

7 Lawson, 396.

8 Lawson, 396.

9 Lawson, 397.

10 “Free-for-All Riot Marks Armour Game,” Omaha World Herald, June 30, 1919.

11 “Jack Marshall,” Omaha World Herald, July 1, 1919.

12 “May Call Off Union Giant Game,” Munster (Indiana) Times, July 31, 1919: 5.

13 Karen Christianson, project director, “Mayor Requests State Militia, Chicago 1919: Confronting the Race Riots, https://exhibits.chicagocollections.org/1919/militia.

14 “May Call off Union Giant Game”’ “Gary Cancels Game with Union Giants,” Munster Times, August 2, 1919: 5.

15 Lawson, 415.

16 “‘Rube’ Assigns Players to Giants,” Chicago Defender, March 20, 1920: 9.

17 “Giants Mobilizing,” Chicago Defender, April 3, 1920: 9.

18 Layton Revel and Luis Munoz, “Forgotten Heroes: David ‘Gentleman Dave’ Malarcher,” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, 2014.

19 Paul Debono, The Chicago American Giants (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2007), 82-83.

20 “League Season Opens Saturday at Giants Park,” Chicago Defender, May 7, 1921: 11.

21 “American Giants Win,” Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1921: 18.

22 Debono, 88.

23 Detroit Free Press, April 17, 1922: 12. Information about the Cowpers is from Chris Rainey, “Fred Schemanske,” SABR BioProject.

24 Debono, 93-94.

25 Debono, 93-94.

26 Debono, 98.

27 “Monarchs to Start Training,” Kansas City (Missouri) Times, April 2, 1924: 14.

28 “Play Two Games Today: Rain Postponed Yesterday’s Monarch-Indianapolis Contest,” Kansas City Times, May 20, 1924: 14.

29 Debono, 103.

30 “Former Mates to Battle,” Kansas City Times, May 18, 1928: 17.

31 “Detroit Stars Win over St. Louis Nine,” Detroit Free Press, July 29, 1928: 27.

32 Richard Bak, Turkey Stearnes and the Detroit Stars (Detroit: Great Lakes Books, 1994), 130.

33 Bak, 131.

34 Bak, 131.

35 “St. Louis Stars Drop Three Games to American Giants; to Play Baltimore Black Sox,” Chicago Defender, September 14, 1929: 9.

Full Name

Jack Marshall

Born

May 11, 1893 at Carrollton, MO (USA)

Died

May 11, 1961 at Wadsworth, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.