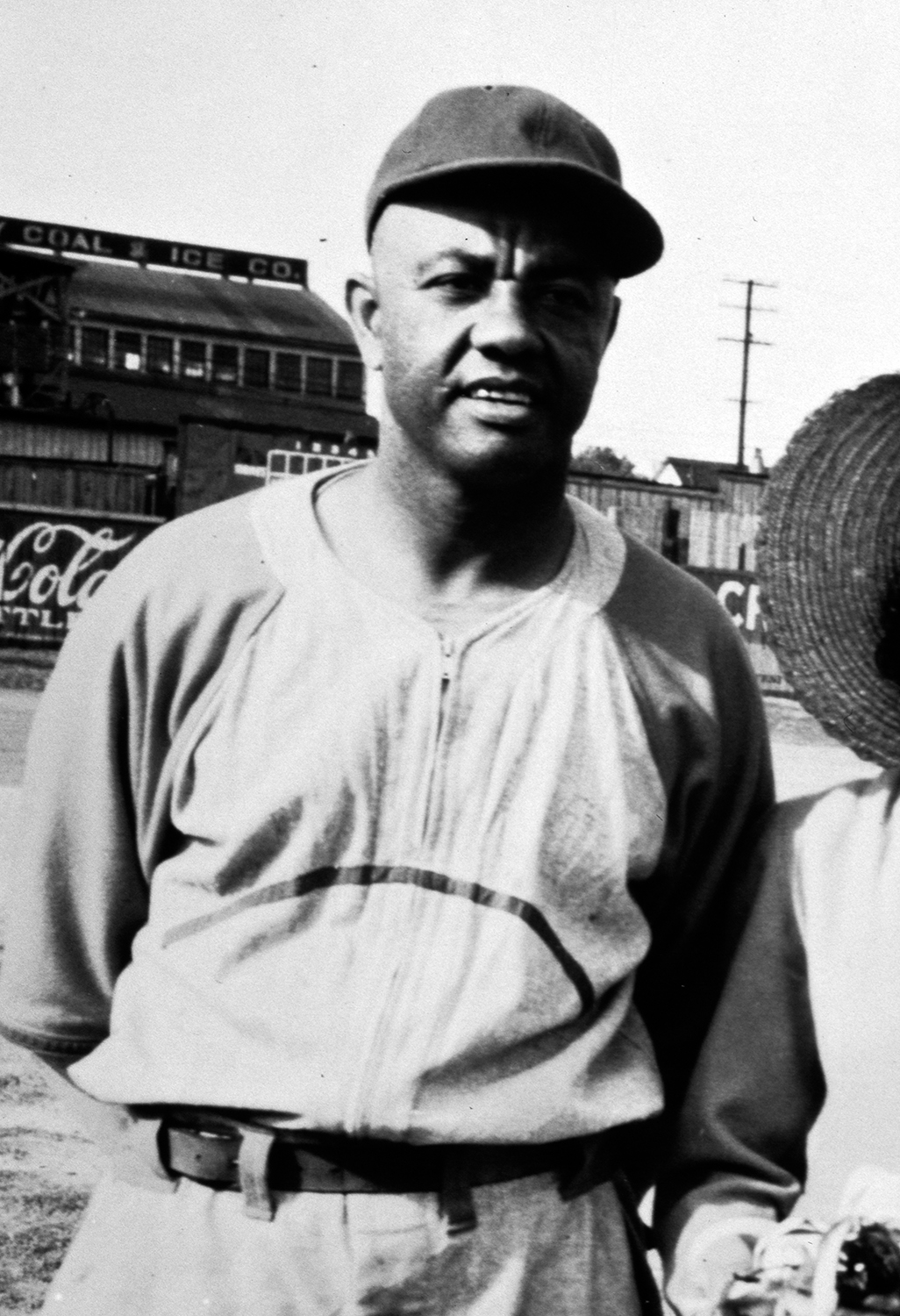

Ted ‘Double Duty’ Radcliffe

“‘Double Duty’ Radcliffe—he was a good one. Pitched and catch. He was a legend.” — Red Moore1

Theodore Roosevelt Radcliffe sported one of the most iconic nicknames in the history of baseball: Double Duty. Few are so evocative of a player’s place in the game. Two jobs at the same time. Two for the price of one. Pitcher. Catcher. And not too bad a manager, either. So, Triple Duty?2

Theodore Roosevelt Radcliffe sported one of the most iconic nicknames in the history of baseball: Double Duty. Few are so evocative of a player’s place in the game. Two jobs at the same time. Two for the price of one. Pitcher. Catcher. And not too bad a manager, either. So, Triple Duty?2

Legend has it that Ted Radcliffe’s moniker came from acclaimed columnist Damon Runyon after Runyon witnessed a doubleheader at Yankee Stadium where Radcliffe caught Satchel Paige’s 4-0 shutout in Game One and then pitched his own 6-0 shutout in Game Two.3 Radcliffe himself recounted this to his biographer Kyle McNary and later in a SABR oral history audio recording.4

Evidence for this is not so certain. No references to Radcliffe, or Negro League baseball at all, have surfaced so far in any of Runyon’s New York American columns during the 1932 season when “Double Duty” first appeared in print. In fact, the Philadelphia Tribune and Pittsburgh Courier offer the earliest sightings in their May editions, implying that the doubleheader in which Radcliffe caught and pitched may have already taken place. Further, the purported doubleheader itself of the Crawfords playing against either the New York Black Yankees or the New York Cubans or Monroe Monarchs has not yet been found. Nor were any Negro League games played in Yankee Stadium the year the doubleheader supposedly happened (which is part of the legend). Radcliffe was known to be loquacious and, at times, a self-promoter. Perhaps tying the origins of the nickname to the famous Runyon helped burnish his credentials. “Double Duty” was a common term in those days and Radcliffe (previously referred to in the press as Ted or Rad) was not the only player in Negro League ball who played multiple roles. Limited rosters required versatility and players of Radcliffe’s talent stepped up and performed more than capably. None of this is to discount or dispute Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe’s skill and renown. It is merely to say that as is the case with many myths, its repetition has given birth to a narrative that has not yet been proven.5

There is much to be thankful for when it comes to hearing Ted Radcliffe’s story in his own words, both through the authorship of his biography with McNary as well as what John Holway and Brent Kelley captured in their oral histories of Radcliffe. His recollections offer great insight into his career as a player, manager, and ambassador of the game.

“I was born in Mobile, Alabama on July seventh, 1902. My daddy named me Theodore Roosevelt Radcliffe. … I weighed nine pounds when I was born. My daddy was a contractor for the shipyard company. He built the houses where the people that made ships lived. … What did my mom do? What’s she gonna do with the 10 of us — five boys and five girls.”6

In the player file that the Hall of Fame asked retired ballplayers to complete, Radcliffe identified his parents as James and Mary. He wrote that he attended Booker T. Washington Elementary School in Mobile for seven years but did not attend high school.

Mobile famously produced an array of major-league talent over the years: Hank Aaron, Billy Williams, Willie McCovey, and Cleon Jones, to name a few. And Satchel Paige. “Me and Satchel was born five blocks apart in Mobile.”7 Like his peers, Radcliffe’s early years were a mix of work and play. “I helped him [my dad]—I was a good carpenter. When I got older and he didn’t want to give me but a dollar a day I came up to Chicago.”8

Meanwhile, “me, Satchel, and Bobby Robinson started playing around together on the lot with a rag ball when we was eight or nine years old. … I don’t remember when I first started to pitch and catch. I think I first started pitching in 1912 when I was ten years old. I always had a good arm. I started catching Satchel and all those big boys when I was 15. … That’s right, I was Satchel’s first catcher and caught him more than any catcher who ever lived.”9

Radcliffe recounted that his first foray into any form of organized ball was with his younger brother Alex Radcliff10, who had his own successful career in the Negro Leagues. Both played for the Mobile Black Bears along with Paige, for whom Radcliffe caught. “That was the best young battery I’ve ever seen,” [Ted] Radcliffe remembered being told.11 Players weren’t paid though, according to Radcliffe. Spurred by what little income he made working for his dad, “in 1919, when I was 17, me and my brother Alex, hoboed up to Chicago. Wasn’t nothing doing around Mobile, so we got tired of it. My oldest brother who lived in Chicago kept telling us to come up, so we did. … All my family came up to Chicago right after us and we lived at 3511 Wentworth—four blocks from the old White Sox Park where the Chicago American Giants played [South Side Park].” 12

Radcliffe attended Wendell Phillips High School on Chicago’s Southside. Living so close to the park, Radcliffe tells the story of getting into games before tickets went on sale and then, “when they started to warm up, we’d get a glove and go out in the outfield and start shagging balls. Sometimes when I was young, they’d ask me to pitch batting practice, and my reward would be a Coca-Cola or lemonade or something.13

Once in Chicago, Radcliffe’s origin story in professional ball took shape. “I started playing with a little team they called the Illinois Giants in 1920. A White guy from Spring Valley named Murphy had the team. There was a playground down there at 33rd and Wentworth where I’d go and play every day. Murphy came there one afternoon to bring his team there in the spring, and I pitched against his team and struck out so many of them.”14

Murphy invited Radcliffe to join the team and because he was only 18, he ran home and asked his father for permission to begin his career in baseball. Radcliffe’s start with the Illinois semipro all-Black team spanned his late teens and early twenties from 1920 into 1927. The team played throughout Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, the Dakotas, and Wyoming, traveling on a bus driven by the owner. In 1927, Radcliffe also played some for Robert Gilkerson’s Union Giants, another traveling semipro team. It was with the Union Giants that Radcliffe met Clarence “Pops” Coleman, who both pitched and caught and who taught Radcliffe the skills to become a catcher.15 Radcliffe’s apprenticeship with the two teams precipitated Bingo DeMoss’s invitation to join the Detroit Stars both as a pitcher and to catch Rube Currie and “Steel Arm” Davis and others in the Stars rotation. However, Radcliffe did not pitch much, if at all; instead, he “caught nearly every day and soon gained a reputation as one of the best throwing catchers in years.”16 With the Stars, Radcliffe also showed that he could hit, both with power and to all fields. Appearing in 65 games, he hit .260 and slugged .413 with eight home runs and 41 RBIs.

In his second Negro League season, Radcliffe was tempted by better offers from the Homestead Grays, the Chicago American Giants, and his old team, Gilkerson’s Union Giants. In fact, he jumped to the latter squad, which called upon him to pitch throughout its barnstorming season across the upper Midwest. Detroit Stars manager DeMoss later invited Radcliffe back for the Stars’ postseason play against both Black and White teams.17

The following spring, Detroit traded Radcliffe, leading to what was truly his breakout year as pitcher, catcher, and hitter. “In 1930, I was traded to the St. Louis Stars for three players: Clarence Palm, a catcher; Roosevelt Davis, a pitcher; and Pop Turner, a third baseman. I went to St. Louis, and we won the championship [over Detroit] by 16 games. I think I pitched in 38 games and caught in 90 and I played some outfield.”18

St. Louis was stocked with an all-star lineup including Ted Trent, George Giles, Dewey Creacy, Willie Wells, Mule Suttles, and Cool Papa Bell. As first-half winners of the NNL, the Stars took on second-half winners Detroit in the championship series. Radcliffe pitched in Game One, giving up five runs in three innings, but was bailed out by St. Louis’s hitting and Ted Trent’s five scoreless frames in relief. Radcliffe mopped up in Game Four, a 5-4 loss to Detroit, and took the loss in Game Five, giving up two runs in the bottom of the eighth in a 7-5 Detroit victory. St. Louis persisted, winning Games Six and Seven to take the series.19

As fulfilling as a title was for Radcliffe, his mantra became, “If they didn’t pay me, I would go.”20 St. Louis didn’t and so he went, early in the 1931 season, to the Homestead Grays, arguably one of the greatest teams ever, Black or White. “The 1931 team of the Homestead Grays—we had George Scales on second, Oscar Charleston on first, Jake Stephens at short, Boojum Wilson on third, we had Vic Harris … Billy Evans … Ted Page … Josh Gibson and me catching … Bill Foster, Smokey Joe Williams, Lefty Williams … that was the best team I ever been on. The 1931 Homestead Grays.”21

However, Grays owner Cumberland Posey had his own money problems. The crosstown rival Pittsburgh Crawfords poached many of the Grays’ better players, including Charleston, Page, Gibson, and Radcliffe, for the 1932 season.22 Crawfords owner Gus Greenlee had already acquired Satchel Paige from the Cleveland Cubs the year before. The Crawfords excelled in 1932 and a January 28, 1933, article in the Pittsburgh Courier highlighted the Craws’ 1932 pitching exploits, led by hurlers Paige, Bell, and Radcliffe. “Ted Radcliffe lived up to his nickname, ‘Double Duty’ by serving effectively as a twirler and a catcher. ‘Double Duty’ turned in 19 victories out of a total of 27 contests.”23

What kind of pitcher was Radcliffe? At 5-feet-11 and 215 pounds in his prime, Radcliffe had the usual repertoire of pitches, but his claim to fame was the other stuff. Said outfielder Jimmie Crutchfield, “Anything they name it, Duty could throw it. You had to watch Double Duty all the time. He could throw those illegal pitches, then argue he wasn’t throwing ’em.” Radcliffe’s own story merits telling. “They called me the emery champ. I was the best at throwing it. I could make my emery ball break any kind of way I want. Got that piece of emery cloth in the chewing gum and slice the ball like that. Then I’d take my finger and open up the seam a little and make it break four feet down.”24

The years from 1933 to 1937 were nomadic ones for Radcliffe, not because his two-way talents were a hard sell, but rather because he, like many of his peers in the early 1930s, followed the money and looked for opportunities to showcase and be paid for his talents. He began the 1933 season at spring training with the reconstituted Detroit Stars, but then moved, first to the Grays, and then the Columbus Blue Birds and New York Black Yankees.25 At that time, the Grays were playing lackluster opposition in a mostly independent schedule, which bothered Radcliffe’s competitive spirit. So, as he later reminisced, “I went with the Columbus Blue Birds. … I played with them for just two weeks because they were just starting out. The owner didn’t have no money so then I went to the New York Black Yankees.”26 His composite statistics for the year were mixed, but his play paid the bills.

Like many of his fellow Negro League standouts in the mid-1930s, Radcliffe succumbed to the lure of semipro ball in the Dakotas, a time when otherwise unassuming towns like Bismarck and Jamestown upped the ante to attract pro talent to their barnstorming squads. Abe Saperstein, wrote McNary, “one of the country’s largest bookers of baseball games, was the pipeline to Negro League players.”27 Many Black ballplayers who made their way to the Dakotas, Radcliffe included, had Saperstein to thank.

Radcliffe himself was first drawn to Jamestown in 1934.28 The team included Barney Brown and according to Radcliffe, “[he] told me about playing for Jamestown, North Dakota. He recommended me and I got Bill Perkins and Steel Arm Davis to come up with me.”29 Radcliffe ended up managing the team, leading the way with a 17-3 record and a .355 batting average.

The 1934 season also included barnstorming against a big-league all-star team including Jimmie Foxx, Luke Appling, Rube Walberg, George Uhle, and others. This was one of many competitions against White competitors in which Radcliffe took part throughout his career. These head-to-head contests included play with Satchel Paige’s All-Stars against Bob Feller’s squads that took place in the postseason in the early to mid-1940s.30

The following year, Radcliffe moved to the Bismarck squad. He was part of a stellar starting rotation of Paige, Hilton Smith, Barney Morris, and later, Chet Brewer, caught by Quincy Trouppe. Neil Churchill, Bismarck’s owner, made an early play for Radcliffe, but he could not join them right away. Radcliffe explained, “At the beginning of the year, Satchel did almost all the pitching for Bismarck ’cause I was having trouble getting my release from the Brooklyn Eagles. See, I had signed a contract with both teams. Abe Manley owned the Brooklyn Eagles, and he made me the manager to keep me there.31 … We had a lot of great players on the Eagles, but Churchill gave me more money than Manley so I ducked out one night and went to Bismarck. I managed Bismarck the rest of the season.”32

Any team worth its salt wants to show how good it is, and Churchill arranged at the height of the 1935 season for his team to play in the inaugural National Semi-pro Championship Tournament in Wichita, Kansas. The integrated squad, led by Paige’s pitching exploits and Radcliffe’s tandem pitching and catching, went 7-0. They defeated the Halliburton Cementers of Duncan, Oklahoma in the final game, 5-2, a complete game by Paige.33

1936 found Radcliffe playing and managing in Arkansas for the Claybrook Tigers. Once again, money talked. With the team named for him, owner John C. Claybrook “came to Chicago and told me he would give me what I was making at Bismarck plus 20 percent of the gate. I couldn’t turn that down.” Later, Radcliffe had the chance to play for a Negro National League all-star team in the Denver Post Tournament but demurred. Instead, he traveled to Mexico to play for Jorge Pasquel, a prosperous multi-industry magnate with a love for baseball. “He offered me $1000 a month and I had to take it. You’d have taken the money, wouldn’t you?”34

Radcliffe began the 1937 season for the Cincinnati Tigers and appeared in his first East-West All-Star game. According to McNary, “Double Duty was approached at the game by Dr. W.S. Martin [co-owner with his brothers] of the Memphis Red Sox and switched teams.”35 Radcliffe told the story: “I went to the Memphis Red Sox, and I stayed with them from 1937 to 1942. … When I went there, they had players making $100 a month, but I wouldn’t have no ballplayers making less than $250 and the owners didn’t like that. But I won three championships in six years, so they had to do what I said to do.”36

Radcliffe’s Memphis years as player and then player-manager spanned most of the period from mid-1937 to 1942, with the occasional side trip that was emblematic of many a Negro League career. The 1938 Red Sox team, including Neil Robinson and Lefty Wilson, were first half champions and defeated the Atlanta Black Crackers for the NAL crown. The 1939 team finished sixth and though Radcliffe did not pitch much, he did use himself occasionally as a reliever.

Along with many of his peers, Radcliffe jumped to Mexico in 1940 and was subsequently among the players outlawed by the NNL’s executives. Radcliffe joined the Mexican League’s winning squad, Veracruz, along with Josh Gibson, Leon Day, Ray Dandridge, Roy Partlow, and Martín Dihigo. They were attracted by the money offered by the owners of the six-team circuit to Negro League ballplayers. According to McNary, “Because Negro Leaguers knew they could get away with jumping to Mexico, some, like Double Duty, did so several times in their careers.”37 Radcliffe himself suggested, “I played in Mexico six years and went down to South America one year.”38

After a full 1940 season in Mexico, Radcliffe returned stateside and led the 1941 Red Sox to a third-place finish at 23-23-2. Radcliffe started the 1942 season with Memphis but then moved on to the Birmingham Black Barons – run by his friend Abe Saperstein – and eventually to the Chicago American Giants. He explained, “People say I jumped to so many teams to get the most money but in the Negro Leagues the owners got together and asked me to go to different teams because I was a drawing card. They were trying to build their teams up.”39

1943 was a different story. Radcliffe was player-manager of the American Giants for the entire season, leading them to the second-half championship of the Negro American League and playoffs against first-half winners Birmingham. The Black Barons prevailed and then signed Radcliffe to catch in the World Series against Homestead. “Their regular catcher hurt his hand, so they asked me to catch for ’em. … The Grays didn’t kick about it, though, ’cause they knew I’d help bring in bigger crowds.”40 Birmingham lost the Series to the Grays but for the 1944 season sought to retain the nucleus of their postseason roster, which included trading for Radcliffe from Chicago for two players and cash.41

Some records suggest that Radcliffe briefly served in the military,42 receiving an early discharge due to asthma, but Radcliffe himself indicated no military service on the player file he completed for the Hall of Fame in 1972.43 Birmingham again lost to the Grays in the 1944 World Series, but Radcliffe had a serviceable season at the age of 41.

Radcliffe started 1945 with Birmingham, but with owner Abe Saperstein gone, his incentive lessened, and he moved to Kansas City.44 As a sign of changing times, Radcliffe noted, “Our shortstop in ’45 was Jackie Robinson. We were roomies.” Not long afterwards, Robinson was recruited by the Brooklyn Dodgers and signed with their top farm team, the Montreal Royals.45 True to form, Radcliffe found other pastures that season, signed by his longtime friend Saperstein to manage the baseball equivalent of the Harlem Globetrotters, a team he would lead off and on for the next several years.46

The Saperstein-Radcliffe connection was a strong one. Radcliffe reflected in later years that “Saperstein was my man, he was my man. He was the greatest friend to the colored athlete of anybody I know today. He’s the great man in the history of Negroes, for helping Negroes. … I was connected with him twenty-eight years.”47

In 1946, he moved again, initially to the Cleveland Buckeyes to rejoin a former teammate, Quincy Trouppe. However, it did not take long for Radcliffe to respond to a request for his services.

“Cum Posey called me and asked me to come to the Grays. He said he had some young pitchers and he needed me to polish ’em up. He always said I was the smartest catcher he’d ever seen. Cum Posey gave me the most money I ever made in the US. In 1946 I was an old man – $850 a month.”48

Radcliffe ended up not catching much, given Josh Gibson’s rebound year from health issues. He pitched some and probably served as much as a coach and mentor as anything. The Grays failed to win the NNL that year, falling to the Newark Eagles. Radcliffe, as was often the case, joined in postseason play with Satchel Paige’s All-Stars against an array of big-league opponents.

1947 marked the beginning of the end for the Negro Leagues, what with Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby leading the way to the AL/NL major leagues. Radcliffe played initially with Homestead, and then went to Mexico, tempted one more time by the pay. Fittingly, the following year, Radcliffe himself helped break the color barrier in two baseball leagues. Wrote McNary, “In April of 1948, Double Duty was signed by the Rochester Aces and became the first black player in the Southern Minnesota [League’s] half century history.”49 Later that summer, Radcliffe joined the South Bend Studebaker factory team and became the first Black player in the Michigan-Indiana League, a semipro team considered by some to be of Triple-A caliber50. The Aces did not play well, but Radcliffe helped lead the Studebakers to the finals, only to lose to Lafayette. He ended his stint with Studebaker batting .312 and leading the team in homers and RBIs.51

In 1950, at the age of 48, Radcliffe ended his Negro League career as player-manager of the Chicago American Giants. The Negro Leagues were slowly being eclipsed in the eyes of African Americans, given the initial, albeit limited, influx of Black players into the National and American Leagues. As a consequence, the quality of play and level of attendance at Negro League games began to decline in parallel.

Alongside Radcliffe’s play stateside and in Mexico, Cuba was an occasional winter stop for him. Cuban baseball chronicler Jorge Figueredo cites action with the 1938-1939 Habana team, where Radcliffe played alongside Martín Dihigo, Luis E. Tiant, and his brother Alex. He pitched in 19 games with a 5-8 record as Habana finished second to Josh Gibson’s Santa Clara team. He then played with the 1939-1940 Almendares side that finished first, hurling in 12 games, seven complete, with a 7-3 record. He also pitched with Habana that winter, appearing in four games.52

The California Winter League was another facet of Radcliffe’s career in baseball. McNeil tracked Radcliffe playing with his brother Alex on the 1938-1939 Detroit Stars entry in the CWL, finishing a distant fourth to the Philadelphia Royal Giants. His Baltimore Elite Giants played head-to-head against Pirrone’s All-Stars in 1943-1944, winning the series 7-5-1. And Radcliffe was with the Birmingham Black Barons in 1945-1946 as part of that club’s West Coast stint.53

Radcliffe appeared in six East-West All-Star Games, three each as a pitcher and catcher.54 He debuted at the August 8, 1937, game for the Cincinnati Tigers, helped by the absence of many players who had opted to go to the Dominican Republic that year. Radcliffe caught the entire game and was lifted for a pinch-hitter in the bottom of the ninth. The East prevailed, 7-2.55 In 1938, Radcliffe tossed four scoreless innings and closed out the game in a 5-4 West victory.56 It was the first of three consecutive pitching appearances in a Memphis Red Sox uniform. The 1939 Comiskey Park game (the first of two) again saw him finish the game with three scoreless innings, for which he garnered the win in a 4-2 West victory.57 Radcliffe was among many not eligible for the 1940 game because of their choice to play south of the border.

In 1941, he was back, but produced a lackluster two-thirds of an inning in the fourth, in relief of Hilton Smith. Radcliffe gave up six runs, but only two were earned because of the errant play behind him. Another pair scored on Buck Leonard’s two-run homer.58 Appearing for the Chicago American Giants in 1943, Radcliffe went 0-for-3 as the West’s starting catcher in a 2-1 West win.59

Radcliffe’s final appearance came at the August 13, 1944, game as a Black Baron – and it was perhaps his finest. His two-run shot in the fifth inning cemented a West lead that they would not relinquish, taking the game 7-4. The Hall of Fame later asked players to submit responses to the question, “What do you consider your outstanding achievement in baseball?” In his own hand, Radcliffe wrote, “hitting a home run [in the] 1944 East-West game with two men on base [actually only one runner was aboard, Archie Ware on second] that won the game for the West.”60 Radcliffe’s blow made him the only player to give up a homer as a pitcher and hit one in East-West ASG history.61

Radcliffe’s last chapter in organized ball was a memorable one. After the season started, he signed on as manager of the Elmwood Giants of the Man-Dak league in 1951 and soon stepped in to pitch and hit. The team did not recover enough from its poor start before his arrival to win the League. However, it performed so well that Radcliffe was brought back as player-manager in 1952, although he stepped away before the end of the season. And then? “I went up to Canada the next two years and played a few tournament games, mostly pinch-hitting, but that was it. 36 years is long enough for anyone.”62

Radcliffe later told historian Holway why he played so long. “I never had a sore arm in my life. I never was prone to injuries. … You see, by me being big and rugged, I never was out much with injuries. I was pretty hefty, see. I weighed 210, 215. With all that padding and stuff on [as a catcher], they couldn’t buffalo me. … You know if I played for thirty-two years, I had to take care of myself.”63

Radcliffe married his second wife, Alberta, on June 6, 1950. After Ted retired, they lived in the projects on Chicago’s Southside, not far from Comiskey Park. Some sources attribute three children to them; however, neither Radcliffe’s Hall of Fame player profile form (completed in his own hand) nor his funeral program list either children of his own or any stepchildren. (Radcliffe’s first marriage, to Ann, lasted from 1932 to 1940.)

As Radcliffe’s New York Times obituary recounted, “In 1990, [he and Alberta] were robbed and beaten, an event that brought Radcliffe’s financial plight to the attention of the Baseball Assistance Team (BAT) which assists elderly players without means. With BAT’s assistance, he moved into a church-run home.”64

The change helped. According to McNary, life was “sweeter in the last decade [for Radcliffe]. Autograph shows and a greater awareness of black baseball has [sic] given Duty and his peers the recognition they have long deserved.”65 He ran a bar for a time on the Southside. But baseball remained important to him and in addition to attending White Sox games, he found other ways to stay connected. He reminisced, “After I retired, Abe Saperstein got me a job scouting with the Cleveland Indians in 1962. He told the owner, ‘I got a man who knows more about baseball than any man around.’” Later, Radcliffe reflected, “The Cubs had scouts that didn’t know half as much as me and they only wanted to give me $600 a month. I didn’t need that shit so I quit.”66

Radcliffe was always a straight shooter. While in Cuba one winter, after his squad beat a team of American League all-stars, he was asked why he was not in the big leagues. He responded, “You have to ask the two Grand Dragons of the Ku Klux … J. Edgar Hoover and Judge Landis.”67

As for the game’s ultimate honor, in his later years he expressed his view that “The Hall of Fame’s nothing but politics anyhow.”68 Radcliffe died in Chicago on August 11, 2005, at the remarkable age of 103. He was buried in Oak Woods Cemetery in Cook County, and is grave marker includes two illustrations: a pitcher and a catcher with a baseball in between. “Negro League Baseball Star,” the marker reads – a humble accolade for a true baseball icon and ambassador.69 Historian Steven R. Greenes calls Radcliffe a super utility player, transcending the one-dimensional label of pitcher, catcher, or hitter. Is he worthy of the Hall? Historian Riley offered the following eulogy:

“There may have been better pitchers, better catchers, better hitters, and there may have been a more colorful player, but there has never been another single player imbued with the diverse talents he manifested during his baseball career.”70

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Donna L. Halper and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Bill Johnson.

Photo credit: SABR-Rucker Archive.

Notes

1 Brent Kelley, Voices from the Negro Leagues: Conversations with 52 Baseball Standouts, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company (1998): 53.

2 James Riley thought this was apt. James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of The Negro Baseball Leagues, New York: Carroll & Graf (1994): 650.

3 Kyle P. McNary, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, 36 Years of Pitching and Catching in Baseball’s Negro Leagues, Minneapolis: McNary Publishing (1994):71.

4 SABR Oral History Audio Recording. https://sabr.org/interview/ted-double-duty-radcliffe-2002/. Clip 1 – 8:10 mark.

5 The nickname’s origin story cites Runyon as the author and involves a Crawfords doubleheader sweep pitched by Satchel Paige winning 6-0 and Radcliffe winning 4-0 at Yankee Stadium against one of three opponents: the New York Black Yankees or the New York Cubans or the Monroe Monarchs. Although Runyon may have written about it elsewhere, none of his daily New York American columns from March 25 to October 31, 1932, mention Radcliffe. The only doubleheader located so far that Paige and Radcliffe tossed together that year was July 8 at Greenlee Field in Pittsburgh against the Black Yankees, with Paige famously pitching a 6-0 no-hitter in the night cap after Radcliffe lost 9-7 in the first game. According to Seamheads, as best known to date, there were no Negro League games at Yankee Stadium in 1932; the Park did not host a Negro League game until 1934. New York Black teams played instead at Dyckman Oval or Dexter Park. It is very important to note that the moniker Double Duty first surfaces (based on research to date) in the May 19, 1932, Philadelphia Tribune. Two days later, the May 21, 1932, Pittsburgh Courier calls Radcliffe Doubleday (not Double Duty). Then, in its edition of June 4, 1932, Chester L. Washington picks up the Double Duty name. Soon after, the press regularly called Radcliffe Double Duty. With the May dates in mind, the Crawfords did play the Black Yankees early in the season, but the games were in Pittsburgh and not until June 5 (captured in the June 11, 1932 New York Age) did Pittsburgh play the Black Yankees in New York at Dyckman Oval, where Runyon may have watched the doubleheader that the teams split (New York won 4-1 and then lost to Paige in the nightcap 14-6). The Crawfords inaugurated Greenlee Field in Pittsburgh on April 29 and 30, splitting the two games against New York. The two teams were to have played a doubleheader at Dyckman Oval in New York on May 1, but it was rained out, as was the planned make-up the following Sunday on May 8. The Crawfords and Cubans did play a doubleheader on June 14 in Pittsburgh with the second game most closely resembling the game Radcliffe described in his oral interview captured on SABR’s website, in which Radcliffe tossed a 7-0 complete game. However, the first game was a 3-1 win for the Cubans, and this doubleheader took place after mentions of Double Duty started appearing in the papers. Finally, Pittsburgh did play Monroe in at least two series in 1932, first in a two-game spring training setting while the Crawfords trained in Hot Springs, Arkansas. The games were on March 25 and 27 in Monroe with the teams spitting the series. Then, in September 1932, the teams played a “world series” in Pittsburgh and Monroe with the Crawfords winning 5-1-1. None of the games were in New York. All of this is to state that definitive evidence remains lacking to substantiate the legend surrounding Ted Radcliffe’s moniker.

6 McNary: 10-11.

7 McNary: 11.

8 McNary: 10.

9 McNary: 11-12.

10 Ted and Alec (or Alex) have had their names variously spelled as Radcliffe or Radcliff. Alec more commonly seemed to use the latter.

11 McNary: 12.

12 McNary: 13-14. Reportedly, Radcliffe was offered a contract to play for a team in Mobile as a teenager, but his father refused to approve the arrangement.

13 John B. Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues, Revised Edition, New York: Da Capo (1992): 174.

14 Holway: 174.

15 McNary: 28.

16 McNary: 35.

17 Per Seamheads, he appeared in one game (as a pitcher) with the Chicago American Giants. He appeared in 32 games with Detroit (31 as catcher, one as right fielder).

18 McNary: 47.

19 John Holway, The Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues: The Other Half of Baseball History, Fern Park, Florida: Hastings House (2001): 261-263.

20 Holway, Voices: 176.

21 Kelley: 11.

22 Riley: 649.

23 Chester Washington, “Sez Ches, And Now—The Craws’ Pitchers’ Records,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 28, 1933: 13.

24 Bill Brashler, Legends of the Negro Leagues: The Story of “Double Duty” Radcliffe, A Player Worth the Price of Two Admissions. 1995; this clipping from the book is included in Radcliffe’s player file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

25 The Pittsburgh Courier tracks Radcliffe’s nomadic journey that year, citing the resuscitation of the Detroit franchise in the new Negro National League to which Radcliffe was probably recruited given his previous ties, then to Columbus, Homestead, and finally New York. See the March 25, May 6, and August 12, 1932, editions of the Courier.

26 McNary: 76.

27 McNary: 79-80.

28 This was a year after the exploits of the Bismarck Churchills had shown a light on baseball up north, winning the state championship against Jamestown with a team stocked with Negro League ballplayers.

29 McNary: 88.

30 Holway: 180. Purportedly, Radcliffe hit .403 and went 3-0 in 22 games captured in the box scores against White competition.

31 The records do not show Radcliffe as the Eagles’ manager.

32 McNary: 100.

33 McNary: 116-120.

34 McNary: 131.

35 McNary: 140.

36 McNary: 140.

37 McNary: 156-158.

38 McNary: 202.

39 McNary: 161, 164. In fact, as the box scores indicated, Radcliffe moved back and forth that year, playing for both the Black Barons and American Giants, managing the latter team. He also made an appearance with the St. Paul Gophers.

40 McNary: 169.

41 McNary: 174.

42 Encyclopedia.com cites Radcliffe serving in the military during the war but released due to asthma. Radcliffe himself does not include this in his wartime timeline. Radcliffe, Theodore Roosevelt (“Ted”) | Encyclopedia.com; last accessed on September 8, 2023.

43 Radcliffe Baseball Hall of Fame Player File.

44 Riley: 649.

45 McNary: 182-183.

46 McNary: 187-188

47 Holway, Voices: 182.

48 McNary: 192-193.

49 McNary: 204-205.

50 McNary: 208.

51 McNary: 216.

52 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company (2003):, 226, 230.

53 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company (2002): 191, 211-215, 224.

54 Riley: 650.

55 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press (2001): 96.

56 Lester: 110.

57 Lester: 125.

58 Lester: 153-156.

59 Lester: 199.

60 Radcliffe Baseball Hall of Fame Player File.

61 Lester: 212-216, 492.

62 McNary: 235.

63 Holway: 185.

64 Richard Goldstein, “Ted Radcliffe, Star of the Negro Leagues, Is Dead at 103,” New York Times, August 12, 2005: 122.

65 McNary: 243.

66 McNary: 245.

67 Kelley: 10.

68 McNary: 245.

69 Theodore Roosevelt Radcliffe in the U.S., Find a Grave® Index, 1600s-Current.

70 Riley: 650.

Full Name

Theodore Roosevelt Radcliffe

Born

July 7, 1902 at Mobile, AL (USA)

Died

August 11, 2005 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.