Jimmy Manning

A competent multi-position defender, a swift and daring baserunner, and a natural team leader, Jimmy Manning1 should have enjoyed a lengthy 19th century major league career. However, a soft bat – Manning was one of the game’s early switch-hitters but under-productive from either side against top-flight pitching – confined him to a five-season turn in the big leagues.

A competent multi-position defender, a swift and daring baserunner, and a natural team leader, Jimmy Manning1 should have enjoyed a lengthy 19th century major league career. However, a soft bat – Manning was one of the game’s early switch-hitters but under-productive from either side against top-flight pitching – confined him to a five-season turn in the big leagues.

The considerable acclaim accorded Manning in his day stemmed mostly from his accomplishments as a team captain, playing manager, and, eventually, franchise owner in several minor league venues, most notably Kansas City. He returned to the majors in 1901 as field manager and majority owner of the Washington Senators of the fledgling American League. But Manning left the game shortly thereafter, and spent the remainder of his life making and losing several fortunes in the business world prior to his death in 1929. His life story follows.

James H. Manning2 was born on January 31, 1862, in Fall River, Massachusetts, a bustling mill town situated about 50 miles south of Boston. He was the oldest of eight children born to Thomas F. Manning (1841-1905) and his wife Catherine (née Whalon, 1842-1922), both Irish Catholic immigrants.3 In time, Tom Manning advanced from common laborer to railroad company employee to retail merchant. He doubled as a Fall River policeman and was an active participant in the affairs of St. Patrick’s Church, as was his wife.4 Their parents’ upward mobility and steadfast life style provided the Manning offspring the benefit of growing up in a stable and relatively comfortable household.

Jimmy graduated from Fall River High School and later matriculated to the Massachusetts School of Pharmacy in Boston. For much of his playing career, Manning would return home to work off-season jobs at local pharmacies, including one operated by younger brother Frank. But like many other athletically inclined Fall River youths, Jimmy gravitated toward baseball. He began playing as a teenage shortstop for local nines and soon graduated to the fast Fall River city league, the spawning ground of Charlie Buffinton, Frank Fennelly, Tom Gunning, Andy Cusick, and other 19th century major leaguers.

In 1883, the 5-foot-7, 157-pound Manning and his companion Gunning made their professional debuts with the Springfield (Illinois) club of the newly-formed minor Northwestern League.5 From the outset, the two presented a sharp departure from the stereotypical hard-drinking Irishmen personified by Chicago White Stockings star King Kelly and/or the rule-bending Celtic hooligans (John McGraw and company) who rose to stardom with the Baltimore Orioles in the ensuing decade. Both Manning and Gunning were serious, highly intelligent, and well-educated men,6 fiercely competitive but clean-playing on the ball field and polished, sober gentlemen off it. Shortstop-third baseman Manning and catcher-outfielder Gunning made favorable impressions while playing for a middling (37-47, .440) fifth-place club and were reserved by Springfield for the 1884 season.7 But the postseason liquidation of the Springfield franchise left the pair free to seek employment closer to home, and they soon signed with the Boston Beaneaters of the National League.8

Manning and Gunning began the 1884 season on the roster of the Boston Reserves, a farm team that the Beaneaters placed in the independent Massachusetts State Association. Jimmy drew attention in preseason practice games against the parent club. “Manning showed up again in good style and promises to be a valuable man at bat and in the field,” reported the Boston Globe in its account of an early April thrashing administered by the varsity to the Reserves.9 Thereafter, a spectacular start against MSA opposition – Manning hit .421 in the Reserves’ first 11 games10 – earned him a quick promotion to the big club.

On May 15, 1884, he made his major league debut playing center field for Boston in an 11-9 victory over the Detroit Wolverines.11 That afternoon Manning registered a single in four at-bats and “took a very pretty fly” on defense in support of staff ace Charlie Buffinton, another of his Fall River friends.12 Proving a useful utility man for Boston skipper John Morrill, the righty-throwing Manning saw action all over the diamond, making 21 combined appearances at second, third, and short, while playing 73 games in the outfield for the second-place (73-38, .658) Beaneaters. He also posted a modest .241 batting average with 52 runs scored and 35 RBIs in 89 games, and garnered a spot on the club’s reserved list for the 1885 season.13

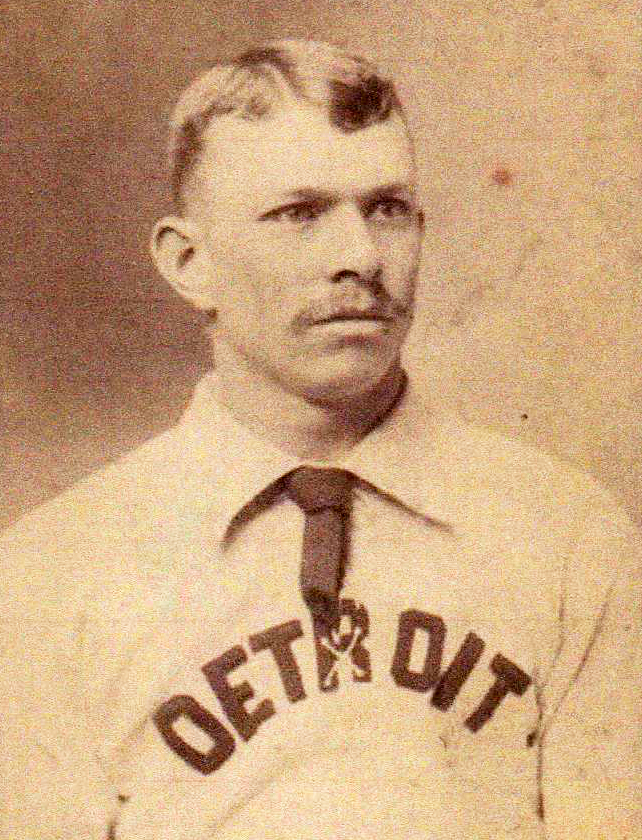

Manning’s performance regressed the following year. Playing primarily in the outfield, he saw action in 84 Boston games but batted a mere .206. In early September, he was sold to Detroit for $500.14 Promptly installed at shortstop, he batted, .269 with Detroit, and was signed for the 1886 season. The mid-winter acquisition of the famed “Big Four” of the defunct Buffalo Bisons – Dan Brouthers, Deacon White, Hardy Richardson, and Jack Rowe – changed the landscape in Detroit. With the hard-hitting Rowe penciled in as the Wolverines’ everyday shortstop, Manning was used elsewhere. Assigned to duty in left field, disaster struck during a May 31 game against the New York Giants when Manning and shortstop Rowe collided “like two locomotives” while pursuing a tenth-inning pop fly.15 The resultant compound fracture to his right wrist sidelined Manning for almost three months.16 Although disappointed with the enforced idleness, he was philosophical. “My injury was the result of one of those accidents which are liable to happen at any time. Nobody was at fault,” he said.17

While he waited out the recovery process, the fact that Detroit kept him on salary throughout doubtless eased his distress.18 He finally returned to the lineup in late August but was essentially a non-factor in the Wolverines’ surge to a second-place (87-36, .707) finish in final National League standings. Limited to 26 game appearances, he batted an anemic 18-for-97 (.186) for the year. Still, Detroit re-signed him for the upcoming season without any cut in pay from the $1,900 salary that he had received since 1885.19

In 1887, the Wolverines were National League pennant winners and postseason World Series champions. Unhappily for Jimmy Manning, he was not around Detroit long enough to enjoy the triumphs. He began the campaign as for-sale material, with the asking price $500.20 But an early season injury to Hardy Richardson necessitated a reprieve. Once again stationed in left field, he promptly played himself off the roster, hitting poorly (10-for-52, .192) and fielding worse (including six errors in 29 innings played as an emergency shortstop). Upon Richardson’s recovery, Manning was released.

In 1887, the Wolverines were National League pennant winners and postseason World Series champions. Unhappily for Jimmy Manning, he was not around Detroit long enough to enjoy the triumphs. He began the campaign as for-sale material, with the asking price $500.20 But an early season injury to Hardy Richardson necessitated a reprieve. Once again stationed in left field, he promptly played himself off the roster, hitting poorly (10-for-52, .192) and fielding worse (including six errors in 29 innings played as an emergency shortstop). Upon Richardson’s recovery, Manning was released.

A lack of interest by other major league clubs reduced Manning to seeking minor league employment. In time he landed a berth with the Kansas City Cowboys of the Western League.21 It was in that rapidly growing Missouri municipality that Manning’s baseball career entered its second phase. Fueled to some degree by the anomalous one-season-only rule change by which a base on balls was deemed a base hit, Manning’s batting average skyrocketed. In 81 games for the middle-of-the-pack Cowboys, he hit an astronomical .433 with 43 extra-base hits among 165 overall, 133 runs scored, and 24 stolen bases, while posting professional career highs in home runs (12) and slugging average (.638).

The Western League folded after the season,22 but the Kansas City Cowboys stayed alive, landing a spot in the major league American Association as a replacement club for the disbanded New York Mets. Manning, however, did not remain with the Cowboys. Instead, he took charge of the Kansas City Blues as playing manager in the newly formed Class A Western Association.23 At the plate, Manning demonstrated that his offensive outburst of the previous season had not been a fluke. Limited by injuries to 116 games, he batted a solid .289, with 32 extra-base hits, and led the Western Association in runs scored (123) and stolen bases (101). He also demonstrated leadership, navigating the Blues (76-42, .644) to the WA pennant.24 A low-key field boss, he was popular with his charges, who presented him with a gold-headed ebony cane at season’s end. Praise for his stewardship was reflected in a wire service dispatch which declared: “Everybody speaks highly of Manning and he is pronounced one of the best managers and captains in the country.”25 Jimmy then capped the year off by signing on for A.G. Spalding’s world-circling exhibition game tour.26

While Manning was preparing for his globetrotting adventure, the financial backers of the American Association franchise in Kansas City and those of the Western Association’s Kansas City team consolidated their operations into a single ball club.27 Thus, when Manning returned from the Spalding tour, he found himself once again a major leaguer. He spent the 1889 season splitting time between second base and left field for the new Kansas City Cowboys. Regrettably, he also reverted to early-career form as a batsman, unable to sustain his gaudy minor league stats of the previous two seasons. In 132 games for the Cowboys, he batted a meek .204, although he did contribute 68 RBIs and steal 58 bases.

Meanwhile, trouble for Organized Baseball – in the form of a restive players union organized by visionary New York Giants shortstop John Montgomery Ward – had been brewing throughout the season. Ownership-player strife culminated in the unveiling of a new major league in early November. Taking the field for the 1890 season would be the union’s eight-club Players League. Having played alongside Ward during the Spalding tour, Manning was an admirer of the rebel circuit’s progenitor and publicly declared himself a Brotherhood man.28 The trouble was that the talent-heavy Players League had little need of a light-hitting utility man; none of its clubs sought Manning’s services. He had another problem: his resident major league club, the Kansas City Cowboys, had been liquidated. Bereft of a contract offer from a National League, American Association, or Players League team, Manning defaulted to signing with the latest incarnation of minor league baseball in Kansas City, the KC Blues of a revived Western Association.29

Although only 28 years old, Jimmy Manning’s major league playing career was now behind him. Over the course of five seasons, his principal shortcoming had been the weak hitting reflected in a .215 batting average. His 298 base hits included 72 for extra bases with eight homers. In 364 games played, he scored 188 runs and drove in 149 more. He had also played tolerable defense at six different infield and outfield positions when judged by the barehanded standards of the 1880s.

Although he was a reluctant returnee to Kansas City, things turned out well in the end for him. When the Blues faltered early under the direction of manager Charlie Hackett, Manning was placed in command.30 Invigorated by its new field leader, the club sprinted to the top of Western Association standings and clinched the league pennant by a game with a final day victory over the Milwaukee Brewers.31 Playing a capable second base (a .932 FA in 644 chances), Manning also chipped in on offense with a .273 batting average and 125 runs scored.32 At season’s end, appreciative teammates bestowed a handsome tea service on their playing manager. The local press was effusive in its praise as well – the Kansas City Times declaring, “Jimmy Manning deserves all the complimentary things that have been said of him.”33

Perhaps more important, the success propelled Manning into baseball’s executive ranks. As the season drew to a close, Blues ownership conferred $500 in stock upon him plus an appointment as club secretary. He was also designated Kansas City’s club representative at upcoming Western Association meetings.34 He returned to the Kansas City helm in 1891 and more press plaudits soon followed. In June, a widely published wire service dispatch proclaimed that “in Jim Manning, the Kansas Citys have a hustling, active, ambitious, enthusiastic captain, and one of the most intelligent and gentlemanly players in the profession.”35 Again playing second base full-time, he batted a solid .299, and led the WA in runs scored (138) and stolen bases (59).36 But in the pennant chase, it was Kansas City’s turn to come up one game short, finishing a close second to the league champion Sioux City (Iowa) Cornhuskers.

At the close of the 1891 season, the American Association followed the Players League into oblivion, and the rest of professional baseball was in turmoil. When the Western Association also abandoned play over the winter, Kansas City and several other erstwhile WA clubs obtained membership in a newly formulated version of the Western League. Manning was appointed playing manager of the Kansas City nine, again called the Cowboys, and turned in another first-rate playing performance. Some 66 games into the schedule, he was batting .303 with 30 stolen bases, and was the league leader in runs scored (76) and base hits (83). But on July 17, the Western League collapsed, throwing Manning and the other WL players out of work. A week later, he accepted the position of playing manager for the Birmingham (Alabama) Barons of the Class B Southern League.37 And as he had two seasons before, he proceeded to pilot a then mid-pack ball club to a league championship.

Over time, Manning carefully husbanded his baseball salary and off-season income earned as a pharmacist. At that time, he was also free of finance-draining family responsibilities. Thus, he built a tidy investment nest egg – and with that money, he entered the ranks of baseball club owners, purchasing a fledgling Southern League franchise in Savannah.38 Assuming his customary role of player-manager, Manning guided his new club to a competitive (53-38, .582) fourth-place finish before the league season ended in mid-August. He also pocketed a reported $6,000 profit on club operations.39 That winter, Manning unloaded the Savannah franchise to a local investor, and reset his sights on a larger, more familiar venue: Kansas City.40

Yet another iteration of the Western League had folded in July 1893, but under the leadership of a dynamic new president, Cincinnati sportswriter/editor Ban Johnson, the circuit tried again in 1894. Assuming triple duty – second baseman/manager/club owner – for the circuit’s Kansas City Blues was Jimmy Manning. In 91 games, he hit .326, with 43 extra-base hits, 107 runs scored, and 41 stolen bases for a third-place (68-58, .540) KC club. In a game-wide season of overheated offense, Manning’s numbers were not particularly remarkable. The same could not be said, however, about off-field events, particularly a mid-July sojourn to Sioux City. Late one evening, intruders crept into the hotel room shared by Manning and club treasurer Frank Dennis, chloroformed the two sleeping men, and made off with over $500, including cash receipts from the road trip.41 The robbers were never identified, and Manning eventually replenished the $400+ in stolen club revenue out of his own pocket. The estimated $10,000 to $13,000 profit that accrued to him from club proprietorship, however, likely softened the blow.42

Long a bachelor, Manning took a bride in January 1895, marrying 18-year-old Mamie (Mary) Dennis, the sister of club treasurer Frank Dennis, at St. Patrick’s Church in Kansas City.43 He enjoyed showing off his new wife, reputedly “the most beautiful woman associated with organized baseball,” and was given to introducing her in public as “the Vice-President.”44 The Kansas City Star, meanwhile, extolled the groom, describing Manning as “one of the foremost men of Kansas City. He has been the successful head of a prosperous advertising business employing a number of hands [and] has done a great deal for the town.”45

Once an extended honeymoon trip east was concluded, Manning set about getting his club ready for the 1895 season, his final one as a regular member of the lineup. The season’s results were much the same as the year before: a third-place (73-52, .584) finish in Western League standings for the Kansas City Blues, and a standout performance by its now 33-year-old playing manager: a .359 BA, with 44 extra-base hits, 145 runs scored, and 39 stolen bases. Manning also made an estimated $15,000-$17,000 as club owner.46 Near the campaign’s end, sports pages were awash in rumors that he was to be engaged as manager of the New York Giants.47 But much to the disappointment of Giants boss Andrew Freedman, Manning declined the post, citing his business ties to Kansas City.48

Apart from a two-game stint as emergency first baseman in 1897, Manning thereafter stayed out of uniform and focused on management. A hard-nosed competitor on the diamond, he operated his ball club as a clear-eyed capitalist. His business model revolved around the low-cost acquisition of untested playing talent, careful development of prospects; and the profitable sale of his best players to major league clubs. As a result of their frequently shifting rosters, the fortunes of his later Kansas City clubs fluctuated dramatically. In 1897, for example, the skill-depleted Blues finished seventh in Class A Western League standings. The next season, Kansas City was the WL pennant winner. For a time, Manning also operated the St. Joseph (Missouri) Saints of the now-Class B Western Association as a farm club for the Blues.49 All the while, he also served as a staunch ally of Western League president Johnson, particularly when it came to foiling the self-interested schemes of John T. Brush, principal owner of the WL’s Indianapolis Indians (and the National League Cincinnati Reds, as well).

Manning’s Kansas City Blues remained a league member when the circuit’s name was changed to the American League for the 1900 season. But the Missouri metropolis was not in Ban Johnson’s plans when he declared the American League a major circuit that fall. Rather, he recruited Manning for the AL’s new Washington franchise.50 When negotiations closed, Manning was majority owner of the Washington Senators, having acquired a 54 percent interest in the franchise for a reported $14,000.51 He then stocked the Senators roster with the crème of Kansas City’s playing talent.52

His arrival in Washington was greeted warily by natives mistrustful of outside club ownership. As expressed by veteran local baseball promoter Mike Scanlon, “There must be Washington people interested and their money invested [in the new team]. Base ball has been dead in Washington for several years past on account of alien ownership, and while I know Jimmy Manning personally to be a first-class manager, he does not belong to this city.”53 The situation worsened when the Senators got off to a slow start, which soon led to hard feelings between Manning and AL president Johnson. In Manning’s mind, Johnson had reneged on a tacit understanding that the league would finance the player acquisitions needed to upgrade the Senators’ talent level.54 Shortly after Washington completed a sixth-place (61-72 .459) season, Manning divested himself of interest in the Senators, selling his stock in the club to minority franchise investor Fred Postal.55

Manning did not remain unconnected to the game for long. After his departure from Washington, he and just-retired Boston Beaneaters star Kid Nichols assumed control of a new Kansas City franchise in a successor version of the Western League.56 With Manning serving as club president and Nichols as field manager, the Kansas City Blues (82-54, .603) captured the circuit crown by an eyelash over the Omaha Indians (84-56, .600). With that final triumph, Manning severed his connection to the club and to baseball.57 Although his name would occasionally be mentioned thereafter when an executive post in baseball became open, he moved on, devoting his energies entirely to business ventures.

By late 1903, Manning was president, principal stockholder, and ace traveling salesman of the Cerberite Powder Manufacturing Company, producer of explosives used in lead and zinc mining.58 In February 1908, at 46 he became a first-time father when wife Mamie gave birth to a son.59 Alfred Thomas Manning would be the couple’s only child. By then, the infant’s father had moved on to the insurance industry, selling policies for Midland Life Insurance Company.60 As later revealed in a Kansas City Press profile, Manning’s post-baseball financial situation proved volatile. He “made and lost three good sized fortunes” before moving to Houston and finding stability in real estate.61 He spent his final years as a Texas land appraiser for the Midland Pacific rail line.

On October 22, 1929, James H. “Jimmy” Manning died from complications of diabetes in Edinburg, Texas.62 He was 67. Following funeral services conducted in Houston, the deceased’s remains were brought home to his birthplace and interred in the Manning family plot in North End Burial Ground, Fall River. Survivors included his widow Mamie, son Alfred, brother Frank, and five sisters. A half-continent away, a fond remembrance published in the Kansas City Star was captioned: “Jimmy Manning, Kansas City’s Peerless Leader of the ’90s.”63

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

Sources for the biographical info supplied above include the Manning file at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; the Manning profiles published in the New York Clipper, September 27, 1884, and Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Vol.1, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011); US Census data and Manning family posts accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise specified, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 Modern reference works like Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet identify our subject as Jim Manning, a name that occasionally appeared in late-19th century newsprint. But he was far more often known to teammates, baseball fans, and the sports press of his day as Jimmy (sometimes spelled Jimmie), the appellation that will be used herein.

2 Wikipedia and recent posts on Ancestry.com give Manning’s middle name as Henry. But no original source for this middle name could be found, and the writer is skeptical. Although popular among mid-19th century American WASPs, Henry was not a name favored by Irish Catholics, resonating of a despotic English monarch and the founder of the Anglican Church. Hugh, or even Howard, seem far more likely middle name candidates.

3 Jimmy’s younger siblings were Julia (born 1864), Elizabeth (1868), Mary Jane (1870), Catherine (1874), Emma (1876), Thomas F. (Frank, 1878), and Jennie (1880).

4 Per “Thomas F. Manning Dead,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Globe, March 14, 1905: 5.

5 As reported in “Base Ball Notes,” (Springfield) Illinois State Register, April 1, 1883: 4, and “Personnel,” (Springfield) Illinois State Journal, April 2, 1883: 8. Ed O’Neil, a Fall River infielder, also joined the Springfield club.

6 His studies somewhat impeded by the baseball season, Manning received his pharmacy school diploma in June 1888. After attending Boston College, Gunning graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School in 1891, specialized in pathology, and later served as longtime medical examiner for Bristol County, Massachusetts.

7 Per “Sports and Sporting People,” Illinois State Journal, September 29, 1883: 5.

8 See “Base Ball,” Illinois State Journal, December 7, 1883: 7.

9 “Base Ball: Regulars 28; Reserves 2,” Boston Globe, April 8, 1884: 5. See also, “Base-Ball,” Boston Advertiser, April 8, 1884: 8: Manning “does good work.”

10 Per Boston Reserves season stats published in the Boston Journal, October 1, 1884: 3. Tom Gunning got off to a slower start and was not promoted to the Red Stockings until late July.

11 As reflected in next-day box scores published in the Boston Globe, Boston Journal, and elsewhere. Modern day reference works mistakenly give Manning’s major league debut date as May 16, 1884. Efforts to correct the error were ongoing as this bio was being composed.

12 Per “A Narrow Escape,” Boston Journal, May 16, 1884: 3.

13 See e.g., “The Reserve List,” Cleveland Leader, October 19, 1884: 3; “The Reserve Men,” Canton (Ohio) Repository, October 17, 1884: 1.

14 As reported in “Sporting News,” Detroit Free Press, September 10, 1885: 6. See also, “Short Stops,” Illinois State Journal, September 20, 1885: 5.

15 Per “Base Ball,” Detroit Free Press, June 1, 1886: 8.

16 Manning’s recovery was prolonged when the physician who first attended him botched the repair job and Manning’s wrist had to be re-set some time thereafter, as reported in “The Injured Fielder,” Detroit Free Press, July 20, 1886: 8.

17 “A Letter from Jim Manning,” Detroit Free Press, June 14, 1886: 5.

18 Per “Base Ball,” Washington (DC) Critic, September 4, 1886: 2.

19 See “Sporting Splinters,” Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, March 12, 1887: 2. Manning had first signed for $1,900 per season in 1885 with Boston, per the Cleveland Leader, February 12, 1885: 6.

20 As reported in “Diamond Dust,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, May 9, 1887: 3. See also, “Base Ball Notes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 5, 1887: 5.

21 As reported in “Manning and Knowlton Signed,” Kansas City Star, May 7, 1887: 1.

22 In 1888, the name Western League was adopted by a new five-club independent minor league circuit having no connection to the previous organization of the same name. This new Western League played only a handful of games before disbanding in June 1888.

23 See “Ball Notes,” Boston Herald, October 14, 1887: 5; “Base Ball Notes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 11, 1887: 5.

24 The (73-40, .646) Des Moines Prohibitionists actually posted a marginally higher winning percentage than Kansas City, but played five fewer games and ended up one-half game behind the Blues in final season WA standings.

25 As published in the Milwaukee Journal, October 26, 1888: 1; Boston Herald, October 22, 1888: 8; and elsewhere.

26 As reported in “Spalding Signs Manning,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, October 26, 1888: 5; “Base Ball,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 26, 1888: 2; and newspapers nationwide.

27 See “Consolidation at Kansas City,” St. Louis Republic, October 24, 1888: 2.

28 See e.g., Freeman, “Kansas City Briefs,” Sporting Life, November 13, 1889: 2; “Chips from the Diamond,” Kansas City Times, November 24, 1889: 10.

29 Per “Flashes from the Diamond,” Omaha Bee, March 2, 1890: 17. See also, “On the Professional Diamond,” New York Herald, May 4, 1890: 24.

30 See “Manning at the Helm,” Kansas City Times, June 3, 1890: 2.

31 Per “A Victory Ends the Season,” Kansas City Times, September 30, 1890: 2.

32 Per final Western Association stats published in the Kansas City Star, October 6, 1890: 3. Baseball-Reference provides no stats for Manning’s 1890 season.

33 See again, “Victory Ends the Season,” Kansas City Times, September 30, 1890: 2, which calculated the Manning managerial log at a scintillating 66-23 (.741).

34 As reported in “Ball Club,” Kalamazoo (Michigan) Gazette, October 4, 1890: 6; “Sporting News,” (Lincoln) Nebraska State Journal, October 1, 1890: 2; “Manning Chosen Secretary,” Kansas City Times, September 20, 1890: 2.

35 See e.g., Base Ball Notes,” Columbus (Nebraska) Journal, June 17, 1891: 5, and (Canton, South Dakota) Farmer Leader, June 11, 1891: 6.

36 Per “The Sporting Arena,” Knoxville (Tennessee) Journal, December 21, 1891: 3. Baseball-Reference puts the Manning stolen base total at 58.

37 See “Kansas City Disbands,” Columbus Dispatch, July 28, 1892: 3; “James H. Manning,” Birmingham (Alabama) News, July 25, 1892: 6; “The Blues Scattering,” Kansas City Star, July 25, 1892: 3.

38 At first, Manning only publicly assumed the position of manager of the Savannah club. See e.g., “Base Ball’s Bright Outlook,” Savannah Morning News, November 2, 1892: 6. Manning’s ownership of the franchise came to light later. See “Base Ball’s Outlook,” Savannah Morning News, November 22, 1893: 4. See also, Joseph Lloyd, “Lloyd’s Gossip,” Augusta (Georgia) Chronicle, April 23, 1899: 8.

39 According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, September 16, 1893: 3.

40 Per “Base Ball a Sure Thing,” Savannah Morning News, January 23, 1894: 4. The terms of the Manning sale of the Savannah club to one Jeff D. Miller were not revealed.

41 As reported in “Robbed in Sioux City,” Kansas City Star, July 23, 1894: 3; “Drugged and Robbed,” Topeka (Kansas) State Journal, July 23, 1894: 3; and elsewhere.

42 See “Baseball,” Milwaukee Journal, September 26, 1894: 8: Manning’s profit: $10,000; “Home Runs,” Boston Herald, October 12, 1894: 2: $12,000 profit; “World of Sports,” Waterbury (Connecticut) Evening Democrat, October 12, 1894: 5: $13,000 profit.

43 Per “Quietly Married,” Kansas City Times, January 9, 1895: 4. See also, “Manager Manning to Marry,” Kansas City Journal, January 4, 1895: 8: “‘Jimmy’ Manning to Marry,” Algona (Iowa) Courier, January 11, 1895: 6.

44 Greg Sullivan, “Fall River Wonders: Spindle City’s Jim Manning Brought Major League Baseball to Washington, D.C.,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Herald News, posted on-line October 24, 2019, quoting Falls River historian Phillip T. Silvia.

45 Kansas City Star, January 9, 1895: 4, which added “Mr. Manning has stored his mind with rich things and has shed radiance on business and social relations. It is natural that such a man should fall a victim to the charms of Kansas City womanhood.”

46 According to “In the Field of Sport,” Omaha World-Herald, October 6, 1895: 10; “Base Ball Notes,” Grand Rapids (Michigan) Press, October 4, 1895: 1

47 See e.g., “New York Wants Manning,” Kansas City Star, September 27, 1895: 1; “Gossip of the Bostons,” Boston Journal, September 24, 1895: 3.

48 See “Manning Declined New York’s Offer,” Kansas City Star, October 13, 1895: 6. At the time, the mercurial Freedman had only had control of the Giants for about ten months and his often-disagreeable temperament had not yet been widely exposed.

49 As noted in “St. Joseph Jottings,” Sporting Life, December 4, 1897: 4.

50 See Sandy Griswold, “Sports of the Week,” Omaha World-Herald, November 11, 1900: 18; “Washington End of Circuit Is Fixed,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 11, 1900: 15; “Kansas City to Drop Out,” Omaha Bee, November 1, 1900: 6.

51 As subsequently revealed in “Syndicate Baseball Now,” Washington (DC) Evening Times, November 4, 1901: 2.

52 At least eight frontline Washington Senators players were graduates of the Kansas City Blues.

53 “Alien Ownership,” Washington (DC) Evening Star, November 14, 1900: 9.

54 At Johnson’s direction, coal magnate Charles B. Somers, owner of the AL Cleveland club, had quietly underwritten the operations of several competing clubs, and Manning was disappointed when the Senators were not similarly made beneficiaries of such largesse. See “Light on the Manning Deal,” Kansas City Times, November 4, 1901: 3.

55 As reported in “Loftus Succeeds Manning,” Washington (DC) Post, November 2, 1901: 8; “Sports in General,” Washington Evening Star, November 2, 1901: 10; “Retirement of Manning,” November 1, 1901: 3; and elsewhere. Manning netted about $1,000 over his original investment in the sale of his Washington stock.

56 As reported in the Omaha Bee and Omaha World-Herald, December 8, 1901, and elsewhere. Nichols had pitched for player-manager Manning on the 1889 Kansas City Blues of the Western Association.

57 The severance of Manning’s connection to the Kansas City club was reported in “Magnate Assembly,” Colorado Springs (Colorado) Gazette, January 19, 1903: 3; “Base Ball Notes,” Washington Evening Star, February 25, 1903: 9; and elsewhere.

58 As noted in “Manning May Manage Washington Ball Club,” Washington Times, January 5, 1904: 8; “Jimmy Manning Has Job Manufacturing Explosives,” Wilmington (Delaware) Evening Journal, December 23, 1903: 8.

59 As documented in State of Missouri birth records accessed on-line via Ancestry.com.

60 Per the Kansas City Star, September 1, 1909: 7.

61 Kansas City Press, September 13, 1912: 1.

62 As reflected in the death certificate for Manning promulgated by the State of Texas.

63 Kansas City Star, October 23, 1929: 22.

Full Name

James H. Manning

Born

January 31, 1862 at Fall River, MA (USA)

Died

October 22, 1929 at Edinburg, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.