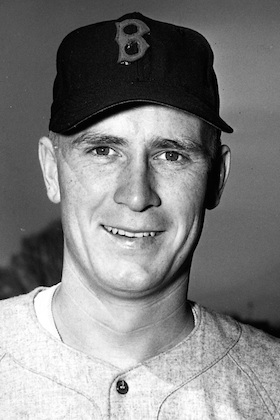

Jim Wilson

Pitcher Jim Wilson was a right-hander who played 16 years in professional baseball, including 257 games in major-league ball over the course of 12 seasons — despite being near death after having his skull fractured by a line drive off the bat of Hank Greenberg. He went on to become the first Executive Director of the Major League Scouting Bureau.

Pitcher Jim Wilson was a right-hander who played 16 years in professional baseball, including 257 games in major-league ball over the course of 12 seasons — despite being near death after having his skull fractured by a line drive off the bat of Hank Greenberg. He went on to become the first Executive Director of the Major League Scouting Bureau.

James Alger Wilson was born in San Diego on February 20, 1922, the sixth child of city policeman George Wilson and his wife, Mary (Rinde) Wilson. Mary’s father, Christopher, came to America from Norway, and George’s mother came from Northern Ireland. George himself was born in Nebraska and Mary in Minnesota. Their oldest, Owen, took up work in a lumber yard by the time of the 1930 census. George Wilson already had more than 20 years on the beat by then.

George Wilson had retired and the family had done some traveling, but they moved to Springfield, Massachusetts, when an opportunity opened up for older brother Rickey Wilson. Jim attended Classical High School 1936-1938, and pitched on the baseball team run by coach Bob Berry. In 1937, at age 15, he threw a four-hitter against Technical High but lost the game because the other pitcher threw a no-hitter. The other pitcher was Vic Raschi.1

The family moved back to the Pacific Coast and Jim finished high school at Seaside, Oregon. He also played some semipro ball in Oregon. He was pitching for a town team in Seaside when Red Sox scout Ernie Johnson first spotted him.2

Jim Wilson started college for one semester at the University of Oregon, but transferred back to San Diego to go to San Diego State.3 He played for them in 1940 and 1941, though more first base and outfield than pitching due to a sore arm. Despite the age difference, Jim and his older brother Rickey (10 years his elder) both played on the same Coronado Ferry semipro softball team in the summer of 1941. Jim had already earned his first letter in college baseball.

He took off 1942 from baseball and spent most of the year working on the ferry boat that ran between San Diego and Coronado. The rest that gave his arm was salutary.4 On September 25, he married Dorothy Ann Herz, whom he had met at San Diego State.

Rickey had become basketball coach at Hoover High, Ted Williams‘s alma mater. The San Diego Union informed readers in April 1943 that Jim had been “an all-around athlete at San Diego State, played second base and pitched for the ball club, and was signed for a professional whirl by Ernie Johnson, coast scout of the Bosox.”5 Wilson received a signing bonus of $1,000, which he said was “contingent on me staying with Louisville all that season of 1943.”6

Wilson became a sizable presence: 6-feet-1 and 200 pounds. His first work as a pro was with the Louisville Colonels in 1943. Having just turned 21 earlier in the year, he had a rough start, with a record of 0-5 in 28 appearances. He’d earned his bonus, though. “I stayed all right, but I didn’t win a game, lost five, and had an earned run average of 5.68 in 57 innings. I guess they must have seen something in me.”7

In 1944, however, he quickly turned everything around, starting the season in spectacular fashion. With the Colonels again, at Parkway Field he started the April 19 opening day game against visiting Columbus and had a no-hitter going through 8 1/3 innings while holding onto a slim 1-0 lead. On a 1-2 count, Redbirds batter Jim Mallory singled. Then things fell apart and a single, a walk, an out, and a single cost him the game. By season’s end, though, he showed more of what Ernie Johnson and Colonels managers Bill Burwell and Nemo Leibold had seen in him. He finished with a 19-8 record and a 2.77 ERA. Wilson’s 19 wins tied him with Earl Caldwell of Milwaukee; his 147 strikeouts led the American Association.

His middle name had been bestowed on him by his mother not because of any reverence for Horatio Alger, but in honor of a schoolteacher from her own past. Nonetheless, his 1944 season was said to have taken him “from zero to hero.”8

Though Louisville had finished in third place in the AA, they won both rounds of the playoffs, four games to two and then four games to none. Playing against the International League champion Baltimore Orioles in the “Little World Series,” Wilson was given the ball in the first game and won, 5-3. After winning his first four playoff games, he started but was crushed, and quickly relieved, as Baltimore won the fifth game, 10-0. The Orioles won the sixth game, and the series, the following day.

The Red Sox had contended for the pennant in 1944, right up there through August until several players left for military service almost all at once. The bottom dropped out. This made them all the more hopeful that Wilson and fellow pitcher Mel Deutsch could come through for them in 1945. Wilson was said to have “blinding speed, but is prone to wildness.”9 It was also noted that he’d played outfield for several games and hit .261 overall, with one homer and 18 RBIs.

In the offseason, Wilson returned to Springfield where he worked in a defense job at the Smith & Wesson plant and played some basketball with the company industrial league team.10

Pitcher Dave “Boo” Ferriss was the big news in 1945. He started his major-league career throwing 22 consecutive scoreless innings and four of his first six starts were shutouts. He won his first eight decisions and wound up a 21-game winner. That would have overshadowed anybody.

Wilson’s debut was disappointing. In a start at Yankee Stadium on April 18, he lasted two-plus innings, walking the first two batters in both innings, and gave up three runs; seven of the 11 men he faced got on base. He bore the 6-2 loss. After two scoreless relief stints, he started again on May 2 and walked the first batter again, but then settled down and pitched a four-hit shutout against Washington. He was 2-for-3 in the game himself and started the winning rally.

Then Wilson lost four starts in a row, by scores of 2-1, 2-0, 3-2, and 5-0. He drew even in wins and losses with four wins in succession, one of them a five-hit shutout against the Tigers, and even won the July 28 game despite twice having walked three batters in a row. (He walked seven in all, but only allowed three hits in a complete-game 6-2 win. In the ninth, he retired the side on three pitches.)

Wilson’s last appearance of the season came on August 8, when he pitched 9 1/3 innings to a no-decision. The Red Sox later scored four runs in the top of the 12th to beat the Tigers.

But his season was over. He had been struck in the head by a line drive off the bat of Hank Greenberg that was hit so hard that “it lifted the Red Sox pitcher right off the ground, spin him around and then dropped him flat on his face.”11 He was knocked unconscious and taken to Henry Ford Hospital; he suffered a fractured skull, the skull split over his right ear. He was operated on but pronounced in good condition the following day. The brain surgeon, Dr. Frederic Schreiber, said the ball had struck “with such force that the imprint of the ball was left in the skull and made a half inch depression.”12 He removed pieces of bone and had to sew up an artery in the head. He said that Wilson would never play baseball again; the Boston Globe front-page headline read: “Pitcher Wilson’s Skull Fractured; Baseball Career Ends.” At least one later story says that quick thinking by Detroit manager Steve O’Neill, to keep Wilson prone on the ground, may have “aided in saving Wilson’s life.”13

Wilson was discharged from the hospital on August 24. He completely recovered by the wintertime and was visited on the West Coast by Ernie Johnson, who told the Sox in January that he was ready to play.

He pitched some in spring training but his first appearance of 1946 came in relief on April 23, the eighth game of the season. The Senators scored four runs in the top of the 11th inning, and Wilson came on, getting the final two outs while surrendering a two-run homer to Jerry Priddy in the process. It was his only appearance for Boston in 1946; the team had everything they need to win the pennant by 12 games over second-place Detroit and he was optioned to Louisville on May 8. Wilson pitched the rest of the year at Louisville and had a good year, a 3.02 earned run average with a 10-6 record, striking out 126 batters in 158 innings.

He pitched all of 1947 for Louisville as well, but didn’t see as much action (4-4 in 12 games), his season cut short by another line drive that shattered his left shin in four places off the bat of Toledo’s Chuck Stevens. On November 17, he was one of six players sent to the St. Louis Browns (along with $310,000 in cash), in exchange for Jack Kramer and Vern Stephens.

Wilson opened the 1948 season with St. Louis, but only faced 18 batters over four relief appearances in late April and May before being released to Toledo. He had given up four earned runs in 2 2/3 innings. He was lucky to have pitched at all. In mid-April, he cut the ring finger on his pitching hand while parking his trailer in Texarkana and in initial reports “the physicians say the injured finger may have to be amputated.”14 The finger was saved, but it was said that year “he never could get started.”15

With Toledo, he was 7-13 (4.01). His contract was sold to the Cleveland Indians in October, then selected in the Rule 5 draft by the Philadelphia Athletics on November 10. The following May, after appearing in two games for the A’s (with a 14.40 ERA), he was returned to the Indians. One story said that the Athletics had drafted him by mistake, that they had intended to draft Bob Wilson but “through a filing error put in a claim for Pitcher Jim Wilson instead.”16

In August the Indians traded him to the Detroit Tigers. Despite all the transactions, he did get in some work. He was 7-11 with a 3.94 ERA for Baltimore and Buffalo combined (Triple-A clubs for the Browns and Tigers, respectively.) In fact, in his first start for Buffalo, on August 17, he threw a 5-0 rain-shortened no-hitter against Jersey City.

Before the 1950 season began, Detroit sent him to Seattle. He pitched the full season in the Pacific Coast League (making a better salary than he previously had in the majors) and had a superb season. Paul Richards, who had been Wilson’s manager in Buffalo, was now Seattle’s manager. Wilson started by losing five games in a row, and then — thanks to his “slip ball” or what was sometimes called a “dry spitter” — went on a spree, winning 15 straight (he didn’t lose once in May or June, and not until July 21), embracing a 40-inning scoreless streak.17 He led the league in wins (24-11, 2.95) and in strikeouts with 228. No one else on the team won more than 13; the Rainiers finished in sixth place. Needless to say, there were many teams interested in him, but a deal had to be done before he was taken in the minor-league draft. Wilson himself said he wanted to stay in Seattle.18 On September 30, the Boston Braves got his contract with a package of cash plus a couple of players to be named later (Mickey Haefner and Emil Verban).19 For the next four years, Wilson pitched for the Braves.

The first two of those years were in Boston, and in 1953 and 1954–after the franchise relocated to Milwaukee—it was for the Milwaukee Braves. He was mostly used as a starter. All in all, he was 31-32 (4.32), with his best year being the 8-2 (3.52) season in 1954. He started off 1951 with a sore arm that saw him have only one start until mid-July, and predictably saw him dubbed “the $50,000 fizzle” by the ever-acerbic Clif Keane of the Boston Globe.20 He was 7-7 (5.40) at year’s end, by no means the kind of year the Braves had been hoping for. In the winters, Wilson worked as recreation director at San Diego’s Presidio Playground, and he worked hard at home in preparing for the coming year. He was 12-14 (4.23) for the seventh-place Braves in 1952. After the team moved to Milwaukee, he was 4-9 that first year—1953—with a 4.34 ERA. He was placed on waivers and no one claimed him for the $10,000 price.

But 1954 proved to be a big year. Though he was used infrequently at first (only 8 2/3 innings through June 1), a back problem for one of the starters opened a slot. He threw a four-hit shutout in his first start of the season on June 6, and then pitched a no-hitter on June 12, 1954, against Robin Roberts and the Phillies, winning 2-0. He credited his slider as working effectively during the game, and Del Crandall for calling the pitches. There was none of the superstition about acknowledging it. “I knew it all the time and we even talked about it on the bench. I never thought it would be a no-hitter until the last man was out, but don’t let anybody tell you he doesn’t know he’s got a no-hitter going. Pitchers usually know how many hits have been made against them. Every one hurts and you don’t forget it too easily.”21 The Phillies tried to hex him by constantly calling out to him from the bench that he had a no-hitter going. The only batter to reach base was Smoky Burgess, who walked twice.

When Harvey Haddix was hurt, Wilson was named to the National League All-Star squad in 1954, but did not pitch in the game. After the season, the Philadelphia Sports Writers Association named him “America’s Most Courageous Athlete.”22

Just before the 1955 season got underway, he was purchased by the Baltimore Orioles (Paul Richards had become O’s manager) on April 13. And, back in the American League, he was sent to the All-Star Game again, though primarily because each team had to have one representative and he was Baltimore’s. Wilson had developed as a pitcher, rather than relying as fully on his fastball as he had. In 1951, he’d developed a sore arm early on, and once it healed he’d realized he’d lost some speed, so he developed a better curve and changeup and even started throwing a knuckleball.23

Working in the A.L. again, he said the strike zone was quite a bit shorter, maybe four inches off the top and several at the bottom of the zone.24 His struggles that year (12-18, 3.44) were due in large part to a lack of run support and maybe some bad luck. After losing a 2-1, 13-inning complete game on May 31 in Cleveland, he lost three more games in June by scores of 2-0, 3-1, and 1-0. His next two wins may have come only because he threw shutouts.

In 1956 he started the season with the Orioles and was 4-2 in the early going before he was part of a six-player trade that sent him to the Chicago White Sox. Wilson was the key man in the deal from Chicago’s perspective; their biggest need had been for another starting pitcher. At one point, he lost eight in a row and he was 9-12 the rest of the way for the White Sox (and for the third year in a row named to the All-Star team), but then had a very strong 1957 season (his five shutouts led the league) with a 15-8 record and a 3.48 ERA. On April 21, he had a no-hitter going through 8 1/3 innings before it was broken up. Wilson’s last season in the majors was 1958, a 9-9 season with a respectable 4.10 ERA. He finished his major-league career as a pitcher with a 4.01 ERA and a won/loss record of 86-89.

He had acquitted himself well at bat, hitting for a career .181 average. When not having line drives carom off him, he fielded well, too, with a career .988 fielding percentage.

A couple of weeks after he announced his retirement in September, Jim Wilson was hired as an area scout by Baltimore for 1959 and worked for them through 1963, covering California south of Fresno, Utah, Arizona, and southern Nevada. After five years, he accepted a position as West Coast scouting supervisor for the Houston Colt .45s from 1964 through 1971 (Paul Richards was the GM at the time of his hire). Wilson’s most notable signings for the Orioles were Jim Palmer and Andy Etchebarren. For Houston, Larry Dierker was his most notable. In the case of the Orioles signings, he shared credit with other scouts.

Wilson then was named Director of Scouting and Player Development for the Milwaukee Brewers in 1972, and was elevated the next year to Vice President, Baseball Operations.

He was VP and General Manager of the Brewers when, on August 5, 1974, it was announced that he would become the first Executive Director of the Major League Scouting Bureau. Brewers owner Bud Selig hadn’t wanted to see him leave, and reportedly promised him a lifetime job if he would stay in Milwaukee. A good summary of the Bureau, its background, and its mission as it launched is provided in the October 12, 1974, Sporting News.25

The bureau initially represented 17 ball clubs, and his staff was to comprise 35-40 fulltime scouts and the same number of part-time scouts, essentially to blanket the United States. Most clubs were expected to keep their own special assignment scouts and cross-checkers. The reports of the scouting bureau would be available to participating clubs in time for the 1975 free agent draft.

As one writer put it more than 10 years later, Wilson was “in effect, baseball’s No. 1 talent scout.”26 The office was based in Newport Beach, California. Wilson himself said, “Our scouting bureau had been a controversial subject all right — hey, some people even call it socialism — but I think the ball clubs have come to realize that it’s the only way to go now. All the pro sports are doing it.”27

A longtime pipe smoker, Wilson died of lung cancer at home in Newport Beach on September 2, 1986.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Wilson’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Thanks to John Gabcik for getting this biography underway.

Notes

1 Mike Vickers, “Jim Wilson Hard Luck Pitcher,” Boston Herald, December 25, 1949: 25.

2 Tommy Fitzgerald, “Alger Tale — From Zero to Hero,” The Sporting News, December 7, 1944: 3.

3 “Face Padre Rookies,” San Diego Union, March 14, 1941: 25.

4 Tommy Fitzgerald.

5 Monroe McConnell, “The Score Board,” San Diego Union, April 15, 1943: 25.

6 John C. Hoffman, “Wilson Winner Because He Wouldn’t Quit,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1956: 6.

7 Ibid.

8 Tommy Fitzgerald.

9 Howell Stevens, “Bosox Basing Box Hopes on Colonel Aces,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1944: 14.

10 Associated Press, “Ex-Classical Tosser Wins First Major Game,” Springfield Republican, May 3, 1945: 5.

11 Jack Malaney, “Sale of Tobin Shocks Boston,” The Sporting News, August 16, 1945: 14.

12 Roger Birtwell, “Pitcher Wilson’s Skull Fractured; Baseball Career Ends,” Boston Globe, August 9, 1945: 1. By sheer coincidence, Birtwell noted, Wilson had taken out an accident insurance policy earlier that very same day. His wife arrived in Detroit to visit him two days later and suffered a nervous breakdown at the hospital.

13 Jim Britt, “As ‘Mike’ Sees It,” Boston Herald, May 7, 1948: 54.

14 “Barber Chair,” San Diego Union, April 16, 1948: 26.

15 Mike Vickers.

16 Mitch Angus, “O’Neill Offered Padre Position,” San Diego Union, November 18, 1948: 25-26.

17 Royal Brougham, “‘Dry Spitter’ Helps Wilson Splash Whitewash on Coast,” The Sporting News, July 26, 1950: 16.

18 Eugene H. Russell, “Valuable Property,” Seattle Times, August 25, 1950: 23.

19 Roger Birtwell, “Braves Buy Jim Wilson; Called Best in Minors,” Boston Globe, October 1, 1950: C45.

20 Clif Keane, “”Holmes Ready to Pitch Wilson,” Boston Globe, June 22, 1951: 13.

21 John C. Hoffman, “Jim Not Superstitious, Knew That He Had No-Hitter Going,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1956: 5. A good account of the game by Red Thisted can be found on page 13 of the June 23, 1954 Sporting News.

22 Art Morrow, “Philly Scribes Hail Wilson as Most Courageous in ’54,” The Sporting News, February 9, 1955: 23.

23 John C. Hoffman, “Wilson Winner Because He Wouldn’t Quit.”

24 John C. Hoffman, “Strike Zone Controversy Flares Anew,” The Sporting News, August 3, 1955: 1.

25 Lowell Reidenbaugh, “Brown Hails Central Scouting as Plus for All,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1974: 17-18.

26 Garry Brown, “Jim Wilson: From Classical High to Baseball’s No. 1 Scout,” Springfield Union, June 2, 1985: 62.

27 Ibid.

Full Name

James Alger Wilson

Born

February 20, 1922 at San Diego, CA (USA)

Died

September 2, 1986 at Newport Beach, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.