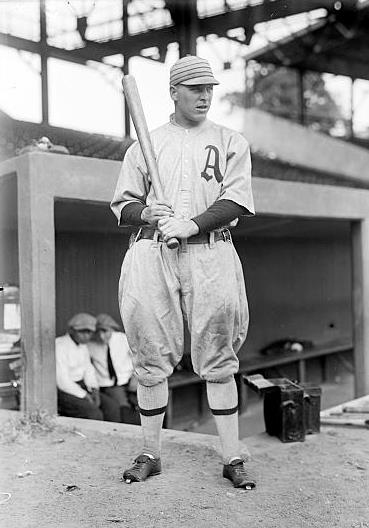

Jimmy Walsh

Jimmy Walsh was among the last natives of Ireland to play in the major leagues. He appeared in 541 games from 1912 to 1917, batting .232 with six homers. He was a member of two American League pennant winners with the Philadelphia Athletics, including the 1913 World Series winners, and he joined the Boston Red Sox for their championship in 1916. After serving in the Navy for a year during World War I, Walsh then resumed his pro career. He continued to play in the minors through 1931, when he was well into his forties. He had a lifetime minor-league batting average of .316. When Connie Mack named his All-Irish team, Walsh was one of the outfielders.

According to many current baseball references, James Charles Walsh was born on September 22, 1885 in Killala, County Mayo, Ireland.1 Walsh’s World War I draft registration showed September 22, 1888, as did the October 11, 1913 issue of Sporting Life. His grave marker also shows 1888. However, his great-nephew has compiled a reliable genealogy, including a birth certificate from Ireland that gives the birthdate as August 24, 1887 — and the place as Rathroe, in County Tipperary.2

The genealogy shows that Jimmy was the ninth of 11 children (seven boys and four girls) born to David Walsh and Mary Hughes. At least three of the older siblings were born in Killala, but Jimmy and his two younger sisters were born in Rathroe. While in Ireland, David Walsh was a farmer, or perhaps a schoolteacher. He left for America with a few of the older children in early 1895. They arrived at Ellis Island on March 4 aboard the ship Aurania. Mary and the rest of the family joined them on another voyage of the Aurania, which docked at Ellis Island on April 2.

The Walshes settled in Syracuse, New York, where David found work as a laborer. They lived in the city’s Irish neighborhood, Tipperary Hill, and worshiped at St. Patrick’s Church there. Jimmy would spend most of his life in Syracuse, and other members of his family would become prominent in central New York politics. His nephew, William F. Walsh (1912-2011), served two terms as mayor of Syracuse from1961 to 1969. Bill Walsh then became a United States Congressman from New York’s 33rd District for three terms from 1973 to 1979.3 Mayor Walsh’s son, James T. Walsh, also represented central New York in the U.S. Congress for ten terms from 1989 through 2009.

Author Sean Peter Kirst described Jimmy Walsh as a “Syracuse sandlot legend.”4 According to a 1916 article in the Geneva Daily Times, a paper from a town in the Finger Lakes region southwest of Syracuse, “Jimmy Walsh is one of the most popular ball players who ever played in this section of the country. He began his career with the old Elmira State League. He and his brother Tommy both played one season with the Geneva team.”5

This differs from a 1911 account in the Syracuse Journal, which said, “Walsh started his professional baseball career in 1906 as a pitcher for Fulton in the Empire League. In 1907 he played with Seneca Falls of the same league. He started as a pitcher, but later, when they were shy an outfielder, he went out in the garden for awhile. By the time the man whose shoes he was filling got ready to get back in the game, Jimmy made such a decided hit with the manager in his new position that he decided to keep him there, and he has played in the outfield ever since.”6

Although there was an Elmira State League, Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide for 1907 shows that Fulton, Geneva, and Seneca Falls were all indeed in the Empire League. The Walsh brothers are not visible in the 1906 Geneva team photo, and the book did not carry a picture of the Fulton club. However, the Seneca Falls team photo includes a player named “Welch” bearing a clear resemblance to Jimmy, and later newspaper stories make it clear that this was an alias. This could have been brother Tommy, “who remained on the staff during the entire season and did very creditable work.”7

In 1932, a book called The History of Central New York described a game from Walsh’s year in Seneca Falls, which is also in the Finger Lakes area. “Probably the greatest game ever played in Auburn was an Empire League duel at the Y.M.C.A. park between Auburn and Seneca Falls. Romer pitched for Auburn. After battling fifteen innings without a score, Seneca Falls scored a home run by Jimmy Walsh. … In Auburn’s half, Romer got a base on balls and ‘Tacks’ DeLavé, a first baseman, hit a home run, winning for Auburn 2-1.”8

Walsh also appears to have played in one game for Syracuse of the New York State League (Class B) in 1907, going 1-for-3. There were two other interesting things about that year: he attended Niagara University, and he too played under the name of Welch. The local papers in central New York and Sporting Life all referred to him that way, including when the Toronto Maple Leafs (then in the Class A Eastern League) signed him late in the season.

“In 1908 Toronto took him along on the spring training trip, but he failed to beat out some of the older and more experienced men and was released. He caught on with Albany and played part of the season with that club. He finished up with Syracuse. ‘Sandy’ Griffin, then manager of the Stars, didn’t think Jimmy had the making of a good ball player and released him during the winter”9 In 94 games, according to Spalding’s Official Base Ball Record, Jimmy batted just .202 in 302 at-bats.10

“Walsh played with [the] Northampton [Massachusetts] team of the Connecticut [State] League in 1909 and at the close of the season was drafted by Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics.”11 His batting had improved to .290 in 96 games. “Jimmy Walsh was among the string of youngsters taken to Atlanta by the Athletics in the spring of 1910. He gave signs of promise, but appeared to need further seasoning, so was farmed out to the Baltimore club for that purpose.”12 The Orioles were then in the Eastern League.

That May, Sporting Life wrote, “When Connie Mack let Jimmy Walsh get away from him, he lost a live one. The lad is knocking the boards off the fence at Baltimore.”13 Walsh also gained a reputation as a good fielder. For example, Sporting Life wrote about the game of July 28, 1910. “All his catches were marvelous, and it was in a sun field at that.”14 Further praise included, “He is a clever boy in the game. He has a scrappy combative disposition without being a loud talker, and he works to win. His fielding is clean and pretty, and his stick work is both timely and of the slugging variety. On the bases he is fast and at all times he does the right thing.”15

Walsh hit a moderate .268 in 140 games with Jack Dunn’s Orioles in 1910, and followed up by hitting .265 the following year. Even so, “his work in the outfield for Baltimore has attracted the attention of at least four big league clubs, and, according to an unofficial report, he will leave the Orioles at the end of the season. . .the chances are that he will go with Detroit.”16

However, in 1912 he remained with Baltimore, which had joined the International League. He hit .354 in 117 games, and Connie Mack finally wanted him in Philadelphia. On August 24, Baltimore sent Walsh and Eddie Murphy to Philadelphia for Claud Derrick, Bris Lord and cash. Sporting Life later quoted Eddie Collins as saying, “Mack only parted with Lord and Derrick because it was necessary to push the deal for Jimmy Walsh and Eddie Murphy through.”17 However, Jack Dunn – with the International League pennant out of reach – was also looking to avoid losing one of his players for the draft price of $2500. It was “a paltry sum,” as Sporting Life remarked, and Mack made an “enticing inducement.”18

Connie Mack and Jack Dunn were good friends who had a long history of making deals together. It’s also worth noting, though, that according to the Baltimore Sun, Mack was alleged to have a financial interest in the Orioles too.19 The Sun’s sporting editor, Cabell Fitzgerald, recanted his view after being shown papers in the club office proving Dunn’s ownership.20 Yet sportswriter Ralph Davis of the Pittsburgh Press still thought otherwise and put it bluntly. Referring to the sale of pitcher Lefty Russell in 1910, Davis said, “It was simply a case of Mack transferring a player from one hand to the other, for, while it might be hard to prove, inasmuch as the Baltimore stock is held in Jack Dunn’s name, nevertheless, the fact remains that the real owner of the Baltimore franchise is Cornelius McGillicuddy, otherwise known as Connie Mack.”21

Walsh got into 31 games with the A’s, hitting .252 with no homers and 15 RBIs. At that time there was already another “Jimmy” Walsh playing big-league ball in Philadelphia, but infielder-outfielder Michael Timothy Walsh – a.k.a. “Runt” – was with the Phillies in the National League. They faced each other in the inter-league postseason series between the Phils and A’s that October.

Walsh made the A’s to start the 1913 season. When Amos Strunk was not available to play center field, Jimmy filled in, and though Strunk’s absence was felt, Sporting Life said that Walsh “played better than a creditable game in centre.”22 Although he got 355 at-bats in 97 games that year, Walsh did not play in the World Series against the New York Giants. Mack used Rube Oldring in left field, Strunk in center, and Eddie Murphy in right for all five games. As sportswriter Hugh Fullerton noted ahead of the Series, “Jimmy Walsh, who is likely to play only in the games that Marquard pitches, is the weakest batsman in the entire outfield squad of the two teams.”23 Marquard started Game One and relieved in Game Four, but what’s more intriguing is that he was a lefty, and current baseball references show Walsh as a lefty swinger. A 1915 article noted that Walsh would substitute for Strunk “when a southpaw appears on the slab.”24 Several text references show Walsh as a righty batter, in addition to a photo.25

Walsh’s batting was unimposing at the top level, as Ty Cobb observed in a January 1914 article. “Walsh was known as a ‘sucker’ on a curve ball at first, but under Mack he got so he could hit curves better than fast ones, although he is not a great batter yet.”26 However, he was speedy (a curious aspect of this was his very small feet: he wore a size 5 baseball shoe).27 Being fast, he took part in crafty little maneuvers of the dead ball era – such as the double squeeze play, in which runners from third and second base score on a bunt. The A’s, in particular shortstop Jack Barry, revived and refined this play (although Hal Chase also did it successfully in 1907). Some accounts hold that Walsh came in from second twice in one game against the Washington Senators, with Eddie Collins bunting. The only instance I have verified came on September 1, 1913, when Barry (in one of his eight successful double squeezes that year) brought him in against Washington’s Walter Johnson.28

After the season, Walsh went to the New York Yankees to fulfill a deal made during the summer, when Yankees manager Frank Chance released Claud Derrick to Baltimore.29 According to the Hartford Courant, “Mack wanted to keep him [Walsh] but had to fulfill his word.”30 Yankees owner Frank Farrell also sent $4,000 to close the deal.31 New York had actually had its pick of Walsh, Tom “Pete” Daley, or Danny Murphy. The Yankees wound up trading Walsh back to Philly for Daley the following June.

Walsh came to terms with the Yankees that January after overtures from Baltimore of the Federal League (he had been highly popular there while a member of the Orioles).32 On April 29, his first big-league homer – a solo shot into the left-field bleachers – was the game’s only run in a win over the Red Sox. The New York Times wrote, “Jimmy Walsh poked a hole in the gray fog at the Polo Grounds yesterday. . .and won the game for the Yanks.”33

Walsh batted just .191 in 43 games for New York, though, as a charley horse nagged him. So he was sent back to Philly. It worked out well for him, as the A’s won the AL pennant. The previous December, Our Navy, the U.S. Navy magazine, had written, “Consider the case of poor Jimmy Walsh. If the Athletics trade him to the Yanks he’ll die of old age before he has another chance to play in the World Series.”34

Jimmy hit three more homers over the rest of the regular season, giving him a career-high four. Ahead of the World Series, there was talk that he might sub for first baseman Stuffy McInnis, whose hand had been injured by a pitch late in the year. Sportswriter Hal Sheridan said, “Walsh has ‘outfielder’ written all over him, however,” and that was where he stayed.35 He was 2-for-6 in three games as the “Miracle Braves” of Boston swept the World Series. Life went on for the White Elephants, though – the day after the Series ended, Walsh served as Bullet Joe Bush’s best man, and he was one of several men from the team who then went on a national barnstorming tour.36

The Athletics plunged to the AL cellar in 1915, finishing 43-109. Mack had begun to dismantle his team and raise cash by selling Eddie Collins to the Chicago White Sox the previous December. Jack Barry went to the Red Sox on July 2, and Eddie Murphy went to the White Sox on July 15. As a result, Walsh got into 117 games, but he hit just .206, with one homer and 20 RBIs.

As the 1916 season opened, Sporting Life wrote, “There ought to be plenty of fun on the Athletic team this year. In the outfield there is Jimmy Walsh, a natural comedian.”37 The Mackmen again needed all the levity they could get, for on the field they limped to the worst winning percentage ever in the modern era at 36-117. Walsh wasn’t around for the end of it, though – he enjoyed another turn of fortune when the A’s traded him to the Boston Red Sox for Raymond Haley. Walsh got into one game in the World Series, going 0-for-3, but was nonetheless part of another champion team.

As the 1916 season opened, Sporting Life wrote, “There ought to be plenty of fun on the Athletic team this year. In the outfield there is Jimmy Walsh, a natural comedian.”37 The Mackmen again needed all the levity they could get, for on the field they limped to the worst winning percentage ever in the modern era at 36-117. Walsh wasn’t around for the end of it, though – he enjoyed another turn of fortune when the A’s traded him to the Boston Red Sox for Raymond Haley. Walsh got into one game in the World Series, going 0-for-3, but was nonetheless part of another champion team.

In his final big-league season, 1917, Walsh continued to back up Tillie Walker, Duffy Lewis, and Harry Hooper in the outfield – Babe Ruth had not yet begun his transition from the mound. Hot stove league chatter in January 1918 said, “The chances are that Jimmy Walsh. . .will return to the Athletics before the opening of next season.”38 Later that month, he joined the Syracuse Fire Department as a ladder man (he had previously been a volunteer fireman in his hometown during the 1911-12 offseason).39

With World War I ongoing, Walsh also tried to enlist as a yeoman in Boston, joining Ernie Shore, Jack Barry, and Mike McNally. However, he “was informed that no more men were being taken into that branch of service,” and he was placed in Class One of the Army draft.40 As it turned out, though, he was able to enlist in the Navy at the end of January. He became a machinist’s mate at the Boston Navy Yard and was “available for Jack Barry’s middy ball nine.”41

Meanwhile, Dublin-born Jimmy Archer played in 42 games for three teams in 1918, while Paddy O’Connor from County Kerry came back for one appearance with the Yankees. In the following century, just two native Hibernians made it to the majors. Pitcher Joe Cleary gave up seven earned runs in one-third of an inning in his only outing in 1945, and then it took until 2018 before Belfast-born pitcher P.J. Conlon arrived.

In March 1919, the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League signed Walsh for their outfield. He only spent one season in the PCL, though, as Seattle sold his contract that December. He spent just about all of the next ten years in the International League, with Akron, Newark, Baltimore, Jersey City, Toronto, and Buffalo. The only time he was away from the IL was 1927, when he spent a stretch with Indianapolis in the American Association.

Walsh kept in shape by playing handball and was considered the top man in Syracuse in that sport.42 He consistently hit well over .300 in the 1920s, including back-to-back IL batting titles in 1925 (.357) and 1926 (.388) for the Buffalo Bisons. He also hit 22 homers in 1925, by far the most in his pro career, and followed up with 17 the next year (Buffalo’s Offermann Stadium was a known hitter’s park). The 1926 season also featured a 31-game hitting streak. In 1928 and 1929, Walsh was still a regular for Jersey City, and he was still capable of hitting .324 and .292. Jimmy and fellow Syracuse player Bill Kelly remained devoted customers of the Kren Baseball Bat Company in their hometown. Sean Kirst wrote, “They’d spend long hours at the plant, trying bats and hanging around the yard.”43

Other highlights of this decade included back-to-back IL championships with Baltimore in 1922-23. Walsh was also manager of Newark in 1921, but the Bears finished at 72-92. Another experience as skipper came with Jersey City in 1924, but with his team in the cellar, he resigned that June.44 He took a couple of weeks off at his home in Syracuse and then rejoined the Skeeters as a player only.

In 1930, Walsh stepped down to Class A, with Hartford of the Eastern League, where he also served as third base coach. In the middle of the year, he accepted another managing job, with Fairmont (West Virginia) of the Class C Middle Atlantic League. He remained a .300 hitter at those levels and also did a good job as skipper. The Sporting News wrote, “Walsh, playing regularly in the outfield, was a God-send to the club.” The Black Diamonds nearly won the season’s second half but fell short because they had to play a tripleheader on the final day.45 After returning to Fairmont in 1931, Walsh put up a .336 mark in 68 games. In late July, however, he and six other players quit over “wage difficulties.”46 He did not return, and his pro career ended.

Walsh remained connected with the game, though, playing for and managing a Syracuse semi-pro team called the Marksons that faced other central New York squads.47 He also umpired in the NY-Penn League in 1935.48 In the late 1930s (probably starting in 1938), he served as a coach with his hometown Syracuse Chiefs in the IL. In August 1939, he showed that his fiery side was still active by “invading the umpires’ dressing-room and taking a swing at Umpire [Chester] Swanson.”49 He was suspended for the balance of the season and all of 1940 as well.50

Walsh remained visible on the Syracuse baseball scene during World War II. In August 1945, the Auburn Citizen-Advertiser wrote about a doubleheader featuring Jimmy’s Syracuse Athletics, who played in the Southern Tier Baseball League. The Athletics boasted a number of big-leaguers; the starting pitchers that day were Jim Konstanty and Walt Brown, who got into 19 games with the 1947 St. Louis Browns. The lineup included Tony Lupien at first, Huck Geary at short, and Chet Ross in the outfield.51

In 1951, Walsh told Jack Durkin of the Syracuse Herald-Journal an anecdote featuring Ty Cobb and Connie Mack. One day, when the Georgia Peach was in a rundown, Jimmy had come in from the outfield to assist. “When the inning was over and I came into our dugout, Connie called me to come and sit beside him. ‘Jimmy,’ he began, ‘it was thoughtful of you to come in from your position. . .but goodness gracious, it’s dangerous enough to risk our infielders against Cobb!’”52 After Walsh died, his nephew Mayor Walsh told a slightly different version of the story, noting that his uncle told many gems – and had the highest respect for Mr. Mack.

Jimmy Walsh was never married. In 1920, he was living in his mother’s home with his brother Thomas and younger sister Bridget (who was known as Della). Jimmy and Della were very close. As of 1930, he was living with Della, her husband Francis Hullar, and their small children. After the Hullars were divorced, Walsh took very good care of her and the children. In 2011, his niece Anna McKenna (then 83) reminisced fondly.

“Uncle Jim was really a father to us as my father had some problems. He had a home built and invited my mother, her husband and us three children to move in with him. He was a real father to us, a sweet, caring, quiet man. He helped my brother, sister and me to go to college. When I was very young, he took me to movies dressed in a white fur rabbit coat! He bought a Stutz Bearcat convertible and drove his sisters around the city. He was a gentle, loving, quiet man. He bought his sisters raccoon fur coats. He was actually shy around people but he had a good sense of humor. He left me his diamond ring which was given to him when he returned after a big season with the Athletics. He was not my father but he was the best father anyone could have!”

Walsh’s regular job was foreman for the Syracuse City Department of Public Works. He retired three years before dying of a heart attack on July 3, 1962, while at the first tee on the Westvale Golf Course in Syracuse.53 He had enjoyed this pastime since at least 1916.54 Anna McKenna said, “I went to a Jesuit college and the Jesuits found out that he was very good at golf. They invited him to play with them on the weekends and he loved it! He died playing golf with them.” While he was still alive, in 1958, Walsh had been inducted into the International League Hall of Fame. Posthumously, he entered the Buffalo Bisons Hall of Fame (1990) and the Syracuse Baseball Hall of Fame (2002).

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Jeff Blair, great-nephew of Jimmy Walsh, for information from his genealogy and to Anna McKenna for her memories (e-mail, August 12, 2011). Thanks also to SABR members Nancy Griffith, Bill Nowlin, and Dennis Pajot.

Originally published on August 30, 2011. Updated May 8, 2018.

Sources

“Jimmy Walsh Dies, Was Pro Ball Player.” Syracuse Post-Standard, July 4, 1962.

www.la84foundation.org (Sporting Life online)

www.fultonhistory.com (various New York state newspapers online)

http://www.syracusehalloffame.com/pages/inductees/1997/jimmy_walsh.html

Notes

1 Baseball references have misspelled this place name as Kallila.

2 E-mail from Jeffrey Blair to Rory Costello, May 13, 2011.

3 Weiner, Mark. “William F. Walsh, former Syracuse mayor and congressman, dies at age 98.” Syracuse Post-Standard, January 8, 2011.

4 Kirst, Sean Peter. The Ashes of Lou Gehrig and Other Baseball Essays. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2003: 119.

5 “Red Sox Buy Jimmy Walsh.” Geneva (New York) Daily Times, August 31, 1916.

6 “Another Syracusan Looming Up as Possible Star in Big Leagues.” Syracuse Journal, June 8, 1911: 6.

7 Chadwick, Henry (editor). Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, 1907. New York, NY: American Sports Publishing Company, 1907: 364.

8 Melone, Harry R.. History of Central New York. Indianapolis, Indiana: Historical Publishing Co., 1932: 192. Art Romer and Edwin “Tacks” DeLavé both went on to play several years in the minors, mainly at Class B. DeLavé was a teammate of Walsh’s at Northampton in 1909. This pitcher/multi-position player, who was also known as “Bug,” was a wrestler as well.

9 “Another Syracusan Looming Up as Possible Star in Big Leagues”

10 Spalding’s Official Base Ball Record, 1909. New York, NY: American Sports Publishing Company, 1908: 174.

11 Ibid.

12 “Big Baseball Deal Involving the Athletics.” Reading Eagle, August 22, 1912: 16.

13 “Philly Pride.” Sporting Life, May 21, 1910: 5.

14 Sporting Life, August 6, 1910: 13.

15 “Baltimore Now Going Well.” Sporting Life, June 11, 1910: 13.

16 “Another Syracusan Looming Up as Possible Star in Big Leagues”

17 “American League News In Nut-Shell.” Sporting Life, February 1, 1913: 11.

18 “Baltimore Makes a Player Deal.” Sporting Life, August 31, 1912: 15.

19 “Lefty Is Dunn’s Prize.” Baltimore Sun, June 24, 1910: 10.

20 “Jack Dunn Baltimore Club Owner.” Sporting Life, August 20, 1910: 13.

21 Davis, Ralph S. “Series Will Be Played.” Pittsburgh Press, September 4, 1910: Sports-2.

22 “Philadelphia Points.” Sporting Life, May 24, 1913: 8.

23 Fullerton, Hugh S. “Fullerton Finds Giants 12 Per Cent Improved.” New York Times, September 26, 1913.

24 “Mack’s New View.” Sporting Life, January 23, 1915: 6.

25 “Athletics Have Lucky Infield.” Trenton Evening True American, July 24, 1913. “Chance Gives Walsh to Mack for Daley.” New York Sun, June 14, 1914. “Big Minor Preparing for Action – Tribe to Play Tigers.” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, January 15, 1922: 39. “Walsh May Join Bisons.” Reading Eagle, December 28, 1924.

26 Cobb, Ty. “Busting ’Em.” Troy Northern Budget, January 18, 1914: 20.

27 Weiss, Bill and Marshall Wright. “1923 Baltimore Orioles.” (http://www.minorleaguebaseball.com/milb/history/top100.jsp?idx=19)

28 “The Athletic Team’s Invention.” Sporting Life, October 4, 1913: 18. “Star Pitchers Lose.” Baltimore Sun, September 2, 1913.

29 “Yankees to Secure a Player from Mack.” Pittsburgh Press, October 25, 1913: 1. “Boston May Send Speaker to Yankees.” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, November 3, 1913: 10.

30 “Jimmy Walsh Now Belongs to Yankees.” Hartford Courant, December 11, 1913.

31 “New Player for Chance’s Lineup.” Spokane Daily Chronicle. December 10, 1913: 18.

32 “News Items Gathered From All Quarters.” Sporting Life, January 17, 1914: 2. “Feds after Jim Walsh.” Baltimore Sun, January 13, 1914.

33 “Walsh’s Home Run Wins for Yankees.” New York Times, April 30, 1914.

34 “Chips from the Block of Sport.” Our Navy. December 1913: 31.

35 Sheridan, Hal. “Old Injury May Keep McInnis Out of Game.” United Press, October 8, 1914.

36 “Local Jottings.” Sporting Life, October 24, 1914: 11.

37 Isaminger, James C. “In the National Spotlight.” Sporting Life, April 22, 1916: 8.

38 “Sport Chatter.” St. Petersburg (Florida) Independent, January 7, 1918: 10.

39 Baltimore Sun, January 23 and February 22, 1912.

40 “Jimmy Walsh Put in Class 1 of the Draft.” Providence Evening Tribune, January 21, 1918: 6.

41 “Sport Chatter.” St. Petersburg Independent, March 20, 1918: 9.

42 “Jimmy Walsh Gives Out Tip on Orioles.” Binghamton Press, February 17, 1922.

43 Kirst, op. cit., loc. cit.

44 “Jimmy Walsh Resigns as Manager of Skeeters.” Rochester Evening Journal, June 21, 1924.

45 Crane, Forrest B. “Fairmont Wants Walsh Back.” The Sporting News, January 8, 1931: 6.

46 “Players, Manager Quit Fairmont Ball Club.” Washington (Pennsylvania) Morning Observer, July 28, 1931: 10. “Cyran Is Manager of Fairmont.” Jeannette (Pennsylvania) Daily News-Dispatch, July 29, 1931.

47 “Jimmy Walsh’s Team Invades Auburn Sunday.” Auburn (New York) Citizen-Advertiser, May 26, 1934: 7.

48 “Walsh a Farrell Umpire.” Auburn Citizen-Advertiser, May 1, 1935: 6.

49 McNeil, Marc T. “Casual Close-Ups.” Montreal Gazette, August 5, 1939.

50 Carroll, Dink. “Playing the Field.” Montreal Gazette, July 23, 1942.

51 “Rain Chases Players from Field, No Game.” Auburn Citizen-Advertiser, August 1, 1945: 8.

52 Baseball Digest, July 1951: 30.

53 “Jimmy Walsh Dies, Was Pro Ball Player.” Syracuse Post-Standard, July 4, 1962. “Jimmy Walsh Dies, Ex-Major-Leaguer.” Associated Press, July 5, 1962.

54 Sporting Life, November 18, 1916: 3.

Full Name

James Charles Walsh

Born

August 24, 1887 at Rathroe, Tipperary (Ireland)

Died

July 3, 1962 at Syracuse, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.