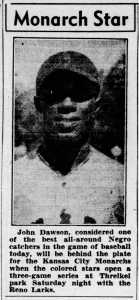

Johnnie Dawson

Johnnie Dawson’s life was bookended by unknowns. His early life was full of uncertainties and the end of his life passed without mention. Even his date of birth is up for debate. Most sources agree that Dawson was born on November 8, but the year varies from 1914 to 1915 to 1916. The birth year most frequently provided in official documents is 1915. Dawson’s name has appeared in newspapers and various records as John Dawson, Johnny Dawson, and Johnnie Dawson, so it seems best to let the man himself decide which is correct. Since Dawson signed his World War II draft card and a marriage license as Johnnie Dawson, that is how his name appears in this chapter.

Johnnie Dawson’s life was bookended by unknowns. His early life was full of uncertainties and the end of his life passed without mention. Even his date of birth is up for debate. Most sources agree that Dawson was born on November 8, but the year varies from 1914 to 1915 to 1916. The birth year most frequently provided in official documents is 1915. Dawson’s name has appeared in newspapers and various records as John Dawson, Johnny Dawson, and Johnnie Dawson, so it seems best to let the man himself decide which is correct. Since Dawson signed his World War II draft card and a marriage license as Johnnie Dawson, that is how his name appears in this chapter.

Johnnie Dawson was born on November 8, 1915, to John and Lucy (Carter) Dawson in Flournoy, Louisiana, a small farming community in Caddo Parish, about 12 miles west of downtown Shreveport. Today, Flournoy is little more than a forlorn interchange on Interstate 20, but it was once part of the sprawling 950-acre Flournoy Plantation, established in 1836 by Tennessee-born Dr. Alfred Flournoy.1 Dawson’s paternal grandfather, Ned Dawson, a mulatto born into slavery in Georgia in 1856, was living in Flournoy as early as 1870, if not before. Ned Dawson was a farmer and landowner. He and his wife, Kitty (Jones) Dawson, had at least 13 children, one of whom was John Dawson, born in Flournoy in 1878. In 1899 John Dawson married Johnnie’s mother, Lucy Carter. During the 1920s, the Dawson and Carter families of Caddo Parrish were active in local and state-level agricultural activities including winning prizes for their crops (Bermuda grass hay, cowpea hay, peanut hay, and squash) and farm products (hams) at the Louisiana State Fair.2 When the oil boom hit northwestern Louisiana in the early 1900s, some of Ned Dawson’s land was leased to drillers.3

None of these accomplishments, however, translated into a stable home life for young Johnnie Dawson. From the start, his family was fractured and scattered. After his parents married in 1899, the family nearly vanished from the record: It was missing from the 1900, 1910, and 1920 Censuses. The only evidence that the family still existed lies in the records of three of their children, all born in Flournoy: Tom Edward Dawson, 1905; Kemp Dawson, 1914; and Johnnie Dawson, born in 1915; these identities have been extracted from marriage and military records. There are no US Census records to indicate that all three siblings ever lived together in the same household.

What happened to Johnnie Dawson’s parents between 1899 and his birth in 1915 is a mystery. The difficulty in researching Dawson’s early years is due to the lack of reliable records and newspaper articles. The overt racial bias of Shreveport-area newspapers resulted in a paucity of items related to African American life. For example, the Caucasian, a Shreveport newspaper founded after the Civil War, had an editorial policy that supported disenfranchisement of Blacks and promoted White supremacy.4 When an article about Caddo Parish’s Black population did appear in print, it usually related to criminal or other unsavory allegations. The Caucasian set the tone for journalism in Caddo Parish for decades to come. During Johnnie Dawson’s years in baseball, Shreveport newspapers largely ignored his accomplishments, as well as those of other African Americans, on and off the playing field.

Shortly after Johnnie Dawson’s birth in 1915, his parents parted company. In 1917 his mother married Franklin “Frank” Niles, a widower with at least two children. Frank and Lucy Niles expanded the household with three children (Johnnie Dawson’s half-siblings): Benjamin “Bennie” Niles, Andrew Niles, and Mattie M. Niles. Frank Niles died on June 10, 1922, at age 38, leaving the widowed Lucy Carter Dawson Niles to raise many dependents on her own. The complexities and uncertainties in his mother’s life and household may explain why Johnnie Dawson and his two brothers spent their childhoods living on farms with various uncles, aunts, and cousins in rural Caddo Parish. By the early 1930s, however, Johnnie and Kemp Dawson were spending more time in Shreveport. The brothers had a little too much time on their hands as evidenced by their arrests as alleged “dangerous and suspicious character[s],” for which they were fined $5 apiece.5

Dawson’s move from rural Caddo Parish to the city of Shreveport set the stage for the start of his baseball career. When Dawson took up the game, African American baseball teams had been playing in Shreveport for nearly 40 years. The first mention of such contests appeared in an article about a tilt between “two colored teams” from Shreveport in 1898, but it is likely that other games took place prior to that date.6 Probably the first Negro organized baseball team in Shreveport was the 1923 Black Gassers of the Negro Texas League, whose games were played at Gasser Park.7

Between 1934 and 1938, Dawson played on at least four teams including the Shreveport All-Stars, Shreveport Tigers (also known as the West End Tigers and Colored Tigers), Shreveport Colored Giants (also known as the Negro Giants), and the Shreveport Black Sports. Based on newspaper accounts of his early career in Shreveport, Dawson was a catcher from day one of his career.

The earliest record of Dawson’s baseball career came at the end of the 1934 season when he played for the Shreveport All-Stars in a series with the Monroe Monarchs for the “state championship.”8 The outcome of the series did not appear in either the Shreveport or Monroe newspapers. It is worth noting that Winfield “Gus” Welch, a mediocre player who hit his stride as a manager, skippered the All-Stars.9 Between 1941 and 1948, he managed the Birmingham Black Barons, the West All Stars, and the New York Cubans. Dawson started and ended his career as a professional baseball player with Welch in Shreveport and ended his career with Welch in Birmingham. Welch had an eye for talent and recruited future Kansas City Monarch Frank “Dick” Bradley out of a Bossier Parish cotton patch in 1935.10 At least one of Dawson’s teammates on the 1934 Shreveport All-Stars also had a professional baseball career: John Matthew “Johnny” Markham, who pitched nine seasons in the Negro Leagues between 1930 and 1945, including hitches with the Kansas City Monarchs, Monroe Monarchs, and the Black Barons.

Dawson’s career began in earnest in 1935 when he took the field as a catcher for the Shreveport Tigers.11 He spent three seasons with the Tigers, also known as the Queensboro Tigers and West End Tigers.12 Dawson’s Tigers had a successful season and the reputation as the champion Negro team in Shreveport and of “the Ark-La-Tex.”13 As the season ended in September, the Tigers’ record was 35 wins against five losses.14 In their last series of the year, they faced a familiar opponent, the barnstorming Shreveport Acme Giants, with manager Winfield Welch and Johnny Markham on the mound. The 1935 series ended in a tie and the rivalry continued into the spring of 1936 when the Giants claimed the city crown by nipping Dawson and his Shreveport Tigers, 7-6.15 One of Dawson’s future Monarchs teammates played for the Acme Giants when they did battle against the Shreveport Tigers in 1935 and 1936 – Hall of Famer Buck O’Neil.

The 1936 season ended for Dawson and the Shreveport Tigers as it did in 1935, with a game against Welch’s Acme Giants. The only difference was that in 1936 the final tilt was rained out rather than ending in a tie. Dawson had a good year in 1936, hitting game-winning home runs in games against the Black Mule Riders of Magnolia, Louisiana, in June, generating pivotal RBIs, and catching a no-hitter for the Tigers.16 His “heavy hitting pulled the locals out of a tight spot” against the Little Rock Black Tigers in August.17 The Tigers claimed the 1936 “Ark-La-Tex crown for colored teams” and the gate receipts with a win over the Black Tigers at Dixie Park in Shreveport.18

Dawson’s best year in baseball was 1937. He started the season with the Shreveport Tigers of the Negro Texas League, but finished with the barnstorming Shreveport Colored Giants (formerly the Acme Giants), a “farm team” for the Kansas City Monarchs.19 Coming off a 51-win 1936 season, the Tigers opened the 1937 season in April with an exhibition game at Dixie Park against the Kansas City Monarchs. The Monarchs were no strangers to Shreveport fans. They had played exhibition games against the Black Sports, a Shreveport nine, as early as 1929.20 The Monarchs, who used Shreveport as a pit stop before heading to Texas and Mexico, defeated the Tigers by a 12-4 score.21

While Dawson was enjoying his best year in baseball, his family life was less settled. His two brothers, Tom and Kemp, left Shreveport for the West Coast and settled in Los Angeles. They were just two of the thousands of African Americans who left Louisiana during the 1930s and 1940s as part of the Great Migration that bypassed industrial cities of the North for sunnier climes in California.22 In fact, Dawson’s mother and nearly all of his extended family left Shreveport for Los Angeles before 1945. Kemp Dawson, like his younger brother, was also an athlete, but he chose boxing over baseball. That may have been a practical matter of form following function. Unlike Johnnie, Kemp Dawson’s massive physique was more suited for combat than catching; according to his World War II draft card from 1940, he was 6-feet tall and weighed 281 pounds. Kemp Dawson’s portly profile earned him the nickname The Blimp in Los Angeles-area amateur boxing circles, and his pugilistic career was not one for the record books.23 In one of his early bouts in 1937, “it wasn’t 30 seconds before tubby Dawson had been deposited on the canvas.”24 One of Kemp’s final appearances in the ring was a cruelly “laughable heavyweight bout” during which his boxing trunks “split in the fore” and “Dawson was led from the ring with a towel draped midship.”25

Meanwhile, back in Shreveport, Johnnie Dawson was enjoying more success behind the plate than his brother experienced between the ropes. All that Johnnie needed now was a change of uniform. In March the Tigers announced that Dawson would return to his backstopping duties for the 1937 season.26 Dawson’s tenure with the Tigers was brief. It ended with an exhibition game against the Kansas City Monarchs at Dixie Park in Shreveport on April 11, 1937.27 As of May 1937, the Shreveport Tigers became the Shreveport Negro Giants or Colored Giants, a traveling team managed by Sam Crawford that played most of its games on the road in the Midwest and the West.28 For one such game, the Colored Giants crossed bats with the Giant Collegians of Piney Woods, Mississippi, on a diamond in Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin, that was billed as an exhibition by “two darkie ball clubs.”29 Shreveport was touted as a “farm team of the Kansas City Monarchs,” with a lineup that included Johnnie Dawson “behind the plate … hitting well over .300.”30

Dawson continued to display his power at the plate as the Shreveport Colored Giants traveled westward to Montana, Washington, and British Columbia. In British Columbia he hammered a homer while going 3-for-5 in a losing effort against the Chilliwack Cherries.31 In Lewiston, Washington, one young fan who came to see the Colored Giants play was so enthused by the experience that he “insisted on blacking his face when he went in the box to pitch for his sandlot team.”32 The press remarked, “But the weather in Lewiston has been a bit hot, he perspired freely, and before the game had gone far it was difficult to determine whether he was Johnson of the Colored Giants or Walter Johnson the Great.”33 If Dawson and his teammates expected less racism in the North, they were mistaken. The following week when they played a game in Laurel, Montana, a local newspaper referred to the Colored Giants as “big [n-word] … mowing everything before them.”34 In Billings, the locals invited Dawson and his Shreveport teammates to a “Dutch lunch” but with the expectation that they would perform for their meal including “entertainment with song and dance novelties.”35

It is likely that Dawson did not enjoy his “Dutch lunch.” By the time he left Montana in late July, he was on the disabled list. When the Shreveport Colored Giants arrived in Wisconsin for a tilt with New London’s Knapstein Brews, the local newspaper touted Dawson as “a hustler,” but the injured Dawson was not in the lineup.36 His next appearance came on August 21, when he played left field during a Shreveport’s 4-2 victory over the Cambridge Danes in Cambridge, Wisconsin.37 Although the nature of Dawson’s injury is unknown, whatever was ailing him took a toll on his power. During the game against the Danes, Dawson went hitless in four at-bats.38 He returned to his catching duties by early September when Shreveport played in a series of games in Iowa to cap off the 1937 season. With Dawson behind the plate, the Colored Giants defeated local nines in Storm Lake and Cedar Rapids. Shreveport’s final road game of the year resulted in a win over the Muscatine Indees “on a diamond in Conesville, Iowa, by a score of 5 to 3.”39 The Muscatine newspaper erroneously referred to the Shreveport squad as the Acme Colored Giants.40 The contest in Conesville was the featured event for the community’s annual Watermelon Day.41

Although 1937 started with a bang and was Dawson’s most productive year, it ended with a whimper. The injury he suffered in Montana in July neutralized his prowess at the plate and, for a time, sidelined him defensively as well Although the precise nature of his injury is unknown, it hindered his effectiveness. Dawson’s 1940 US Army draft card provides some possible insights. According to the document, Dawson’s distinguishing physical characteristics included a “scar on the left side of the forehead,” and a broken “right forefinger.” In any event, the cumulative effects from his injuries contributed to his decline. James A. Riley’s assessment of Dawson as having “an average arm but below average in other phases of the game” was true as far as Dawson’s Negro League career was concerned.42 His best days on the diamond were already mostly behind him by the time he signed with the Kansas City Monarchs in 1938.

Dawson returned to the Shreveport Colored Giants in the spring of 1938 and was off to a good start. In the first game of the year, he banged out a double as Shreveport defeated the reigning Negro National League champions, the Homestead Grays, 6-2.43 The victory was bittersweet as it was the swan song for the Shreveport Colored Giants. Within a week, they disbanded and reconstituted themselves as the Shreveport Black Sports, members of the Negro Texas League.44 The “Sports” moniker was a clever play on a common abbreviation for Shreveport – “S’port.” The Black Sports dubbed Dawson as their starting receiver.45 However, just as he was set to take up his mitt with the Sports, the Monarchs came calling.

Dawson made his debut in the major Negro Leagues with the Monarchs as he joined the Monarchs’ cadre of catchers that included starters Harry Else and Frank Duncan. Dawson’s first game with the Monarchs took place in Chicago on July 31, 1938, when he replaced Else in the lineup during a 7-2 loss to the Chicago American Giants.46 The next day the Monarchs traveled to Davenport, Iowa, for an exhibition tilt against the Illinois and Iowa All Stars before a crowd of about 800.47 The Monarchs dethroned the All Stars, 6-1, giving Dawson his first taste of victory in a Monarchs uniform, albeit in a nonleague game.48 It was not a sterling debut for Dawson given that he went 1-for-4 at the plate and was charged with two passed balls behind it.49 Dawson had two more appearances as a Monarch in 1938, but neither effort did much to merit promotion to starting catcher. He replaced Else in the top of the ninth during the second game of a doubleheader against the Indianapolis ABCs.50 The Monarchs won both games and Dawson’s only “contribution” was one passed ball in one half-inning of work.51 His final appearance was a rare starting role with the Monarchs in a 12-9 victory over the Birmingham Black Barons.52 For this, the final league game of the Monarchs’ season, Dawson reunited with his former batterymate from the Shreveport All Stars, Johnny Markham, who relieved starter John “Big Train” Jackson.53 After the game, the Monarchs left Alabama without Dawson as they headed out on a barnstorming tour.54

Out of a job with the Monarchs and back home in Shreveport, Dawson landed right back where he had started the year – catching for the Shreveport Black Sports. Returning with him were three fellow former Monarchs and Louisiana natives: pitcher Frank Bradley, outfielder Willie “Bill” Simms, and second baseman Willie Horne.55 The reunion lasted just one game, a season-ending contest against the Galveston Bucs, the outcome of which did not appear in the Shreveport newspapers.

Dawson did not play for a Negro League team in 1939. He spent the bulk of the baseball season with the traveling edition of the New Orleans Crescent Stars, former members of the defunct first edition of the Negro Southern League. Once more Dawson found himself managed by Winfield Welch. In late April, the Crescent Stars kicked off their 1939 campaign by barnstorming with Satchel Paige’s All-Stars through towns in east Texas, all within a hundred miles of Shreveport.56 The Crescent Stars’ Texas campaign concluded in city of Tyler, hometown of Negro League catcher and 2006 Baseball Hall of Fame inductee Louis Santop.57

After parting company with Paige’s All-Stars in June, Welch, Dawson, and the Crescent Stars headed to Canada for a tour with “Ham Olive’s Bearded House of Davidites.”58 The two teams spent most of the summer of 1939 in Canada and the Northern US. For Dawson, the higher latitudes did much to improve his baseball attitudes, and he was lauded as “one of the smartest catchers seen here in many a day.”59 In the Crescent Stars’ 7-3 victory over the Davidites in Calgary, Dawson “made several almost impossible catches and time and again drew the applause of fans.”60 He rediscovered his batting prowess of early 1937 and produced a .315 batting average with 10 home runs.61 Perhaps Dawson’s return to form was inspired by the company of two very different individuals with whom he shared the summer of 1939. The first was the Crescent Stars’ pitcher, Johnny Blackwell, a student-athlete at Fisk University and likely the first collegian Dawson encountered as a teammate.62 The second was Helen Stephens, who toured with the Davidites as the “famous Missouri girl athlete” and the holder of 14 “world, Olympic and Canadian records.”63 Stephens was more than just a sideshow act; during her remarkable life, she broke sporting records and societal barriers for women. Among her many accomplishments were earning a Gold Medal in the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, playing professional women’s basketball, joining the US Marine Corps just after World War II, and charting a career for herself with the Defense Mapping Agency in St. Louis.64 That summer, Stephens, who was White, also performed track event exhibitions with Jesse Owens and the House of David aggregation as well as other Negro League teams such as the Pittsburgh Crawfords.65

Dawson capped off his 1939 season as a member of the South All-Stars in the Negro North-South game, held in early October at Pelican Stadium in New Orleans, though he did not play in the game.66 The South’s skipper, Winfield Welch, chose Larry “Iron Man” Brown of the Memphis Red Sox over Dawson to work behind the plate.67 Welch’s choice of catcher for the all-star tilt was of little significance, however, as the North All-Stars demolished the South All-Stars, 10-1.68 The following year, Dawson revisited this also-ran relationship when he crouched in Brown’s shadow for nearly the entire 1940 season with Memphis.

Although Dawson saw no action in the major Negro Leagues in 1939, he made up for it in 1940 when he played for two teams, the Chicago American Giants and the Memphis Red Sox. Something else that Dawson did twice in 1940 was to appear in census enumerations in two different cities. In April, a census taker counted Dawson as part of his mother’s household on Abbie Street in Shreveport. Two months later he was counted again, this time in Memphis, where he roomed with manager Ruben Jones and six of his Red Sox teammates, in a boarding house on Florida Street, just about a mile from Martin Park, the club’s home field. Dawson stated his occupation as a professional ball player on both occasions.

Dawson made his first appearance as a catcher for the Chicago American Giants during an exhibition junket through Arkansas and Tennessee.69 He jumped from the American Giants to the Memphis Red Sox by mid-May and remained with Memphis for the balance of the season. Dawson played in four league games for the Red Sox in place of starter Larry Brown, but he generated only a paltry .125 batting average. Conversely, Brown had a stellar year in 1940, with Cum Posey dubbing him as an “All American” catcher in the Pittsburgh Courier.70 Dawson did accomplish something of note that year; he earned his first nickname. In August, during a swing through the East Coast, a Red Bank, New Jersey, sportswriter tagged Dawson with the moniker Pepper Pot Dawson.71 The reporter gave no justification for naming Dawson after a type of an African-style soup that was popular in the Philadelphia area.72 Although baseball scribes assigned the nickname to describe the “peppery” play and banter of St. Louis Cardinal Johnny “Pepper” Martin, the name did not stick to Dawson.73 He finished the rest of his career without a catchy nickname, an unusual occurrence, especially in the Negro Leagues. One other thing that did not stick around was Dawson himself. Pepper Pot Dawson found himself in the soup about a week later when Memphis dropped him from its roster just before the team headed to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in September to face the Homestead Grays for the deceptively billed “Negro World Series.”74

In October 1940, Dawson registered for the US Army with his local draft board. He was unemployed, living with his mother, and described as standing 6-feet-1 and weighing 176 pounds, with a scar on his forehead and a broken finger. Sometime later, Dawson’s home address on his Army document was edited to read “920 E. Ninth Street Kansas City,” Missouri.

Despite Dawson’s inclusion in a photograph of the 1941 Memphis Red Sox, he did not play for Memphis in 1941.75 When he first donned his catcher’s mask that year, it was as a member of Satchel Paige’s traveling all-stars. In June Dawson caught both games of a doubleheader for Paige’s amalgamation in Cincinnati against the Ethiopian Clowns, reported to have been Paige’s first-ever appearance in the Queen City.76 After splitting the twin bill with the Clowns at Crosley Field, Dawson and Paige’s All-Stars headed to South Bend, Indiana, where they edged the local Studebaker Athletics, 1-0.77 Paige tossed his usual three innings of work and Dawson went hitless in three plate appearances.78 Dawson and Paige’s nine returned to Cincinnati for another go at the Clowns with similar results – another split decision.79

After his stint with Paige’s traveling show, Dawson was signed by the Monarchs once again, though he did not appear in any official league games that season. Joe Greene was crowned as the Monarchs’ starting catcher and Dawson was shunted off to the Monarchs’ B-team barnstorming franchise. He spent most of the summer of 1941 bouncing around the backroads of Oregon and Montana with the House of David nine, under the tutelage of player-manager Walter “Newt” Joseph.80 It was a long and grueling slog. After a 14-0 massacre of the Eugene Athletics in July, a local sportswriter noted, “The tiring [Monarchs], who traveled over 400 miles by car in Oregon’s worst heat wave in years,” still managed to pound out 18 hits, one of which was an RBI contributed by Johnnie Dawson.81 By the end of July, his road trip was over. Dawson had managed a few bright moments at bat – a double here, and a homer there – but it was becoming clear that the sun was setting on his career as a professional baseball player.

In the spring of 1942, the Unites States was at war when Dawson left his mother’s house in Shreveport to return to Kansas City for his final season in Negro League basebal1. Dawson wore number 14 on his uniform that year and was one of four catchers on the Monarchs roster. He was the third-string catcher behind starters Joe Greene and Frank Duncan.82 Dawson appeared in nine league games with the Monarchs in 1942, and his abysmal .100 batting average kept him in a supporting role. A rare highlight for Dawson occurred in April, during an extra-inning game against the Homestead Grays at Pelican Stadium in New Orleans, when he hit a walk-off single that sent Monarchs center fielder Willard Brown across the plate in the bottom of the 10th to clinch the game for Kansas City, 5-4.83 Such moments were rare for Dawson, and overall it was a season to forget. In a battle against the Birmingham Black Barons in June, his frustrations boiled over and resulted in his ejection from the game for cursing the umpire.84 As the summer of 1942 progressed, Dawson wearily barnstormed across the Eastern US – including tilts against the Green Sox of Fremont, Ohio, and the Quakers of Scranton, Pennsylvania – the former described as a “listless battle” with the locals highly critical of his batterymate Satchel Paige’s “lackluster play.”85

Dawson’s final appearance in a league game for the Monarchs came on July 26, 1942, “Satchel Paige Day,” when he donned his mitt in relief of Duncan in a losing effort in the first half of a doubleheader against the Memphis Red Sox at Wrigley Field.86 Paige won the nightcap against Memphis, but Dawson was not in the lineup.87 His backstop work with Paige in Scranton a few days later was likely Dawson’s final appearance wearing number 14 for the Monarchs. He was listed as a possible starter for a Monarchs exhibition game against the Philadelphia Stars at Island Park Field in Harrisburg on August 12, but the weather intervened.88 In mid-August Monarchs manager Frank Duncan released Dawson from the Monarchs, thus denying him an opportunity to appear with the team in the 1942 Negro League World Series.89 Duncan made the move to make room for a new catcher, Frazier “Pep” Robinson, previously with the Baltimore Elite Giants, to replace Dawson as the backup to injured starting catcher, Joe Greene.90 Pep Robinson’s nickname had more to do with sarcasm than with the spiciness of a pepper pot. Robinson generally lacked pep and was also known as “Slow,” a nickname given to him by Paige.91 This was the “only lineup change that Duncan deemed necessary to get the Monarchs to another league and negro [sic] world championship.”92 As it turned out, Robinson did not add any more pep to the Monarchs than Dawson, and he saw little action after Greene returned to the lineup.93

After his mid-August release from the Monarchs, Dawson signed with the Black Barons. It is possible that Birmingham made the move because they were without the services of their regular catcher, Paul James Hardy, who was in Chicago to play in the East West All Star Game.94 Dawson’s old friend and mentor, Black Barons manager Winfield Welch, may have also facilitated Dawson’s merger after Birmingham lost eight players to military service.95 Dawson debuted with his new team on August 15, 1942, as the starting catcher in the first game of a doubleheader against the Cincinnati Buckeyes, which featured a “Jitterbug Contest.”96 Perhaps it was Dawson who was doing the jittering as another backup backstop for the Black Barons, Harry Barnes, relieved him of his duties.97 For Dawson, his stint with the Black Barons was like déjà vu all over again; once more, he found himself as the understudy to Paul Hardy.

Dawson’s tenure with the Black Barons was brief and unremarkable. Out of World Series contention, Birmingham spent the bulk of August and September barnstorming in the Midwest to capture as many gate receipts as possible. Box scores for such games were rare, making it difficult to determine Dawson’s contributions. In the waning days of the summer of 1942, Dawson was the starting catcher in a just a handful of games and saw some action in right field and at third base.98

In mid-September the Black Barons toured through Missouri and Indiana with the Ethiopian Clowns. Dawson was the starting catcher when the Clowns swept a doubleheader at Victory Field in Indianapolis, 3-1 and 7-4.99 His name last appeared in a line score as part of the battery for the Barons in an embarrassing 6-5 loss to the Clowns in Springfield, Illinois.100 The Barons and Clowns shared 10 errors and a meager payday from the gate receipts from the 300 fans who braved the bitterly cold weather.101 On September 22, 1942, they played the two final games of their road trip at City Stadium in St. Joseph, Missouri.102 It was a bizarre doubleheader in which the winner of the opener earned the right to play the nightcap against the Monarchs, who the night before had engaged in a controversial World Series game in which the Homestead Grays used ineligible players to defeat Kansas City, 4-1.103 The Black Barons earned the right to play the Monarchs after dispatching the Clowns, 7-2, and then vanquished Kansas City, the soon-to-be Negro League world champions, by a score of 5-0.104 With no box score to rely on, it is unclear if Dawson took the field for the Black Barons’ victory that night. The line score indicates that he was not the catcher for either contest, but, given the team’s bare-bones roster, it is possible that he took the field in some capacity. For Dawson, there may have been some element of satisfaction in defeating the Monarchs since they had released him right before their World Series run. However, there was little pride to be felt given that 10 errors were racked up and both teams’ lineups were so threadbare that the Black Barons’ 42-year old skipper, Winfield Welch, pitched the first game while the Monarchs manager, Frank Duncan, stepped in as Kansas City’s catcher for the nightcap.105 One local sportswriter was so appalled by the lack of effort that he claimed that the “Clowns were quite frank about not wanting to play the second game,” and that the “Barons were not carrying their advertised stars.”106 He accused the Clowns and Black Barons of being “interested only in grabbing their share of the gate and getting out of town.”107

By late September it was clear that Dawson and his Black Barons were running on fumes, due to players leaving the team to serve in the military. Even Birmingham’s bus went missing after an accident on an Indiana highway that totaled the vehicle and left the players no choice but to take a train back to Birmingham for their final homestand.108 Dawson and his teammates escaped the calamity uninjured.

The last game of the Black Barons’ 1942 season was against the Negro American League All-Stars. It was also the swan song for Dawson’s career in Negro League baseball. The game took place at Rickwood Field on Sunday, October 4, 1942, and the Black Barons defeated the All-Stars by a 6-3 score.109 Black Barons owner Tom Hayes promised the players a “generous portion of the gate receipts” that would serve as a year-end bonus.110 For some Birmingham baseball fans, however, the victory brought no joy to the Magic City. The criticisms voiced in St. Joseph, Missouri, regarding lackluster play followed the Black Barons to Birmingham. The event at Rickwood was dismissed by one columnist who reported that fans complained that the “teams were badly jumbled as far as the lineups were concerned, and it seemed as though it was just something thrown together to get the fans’ oney.”111

After this final debacle, Dawson and his Birmingham teammates “packed their respective grips and departed for their respective homes.”112 For Dawson, that meant using his bonus money for bus fare to return to his mother’s house on Abbie Street in Shreveport. Dawson had little downtime after arriving home. On January 24, 1943, he reported to his local Caddo Parish draft board. On February 3, 1943, Dawson enlisted as a private in the Army, and, according to his enlistment documents, he was 6-feet tall, weighed 173 pounds, and possessed a ninth-grade education. His occupation category was “Athletes, sports instructors, and sports officials”; however, after he joined the Army in 1943, Dawson would never again claim the title of “professional baseball player.”

During World War II, Dawson was stationed in Southern California, where he reunited with his brothers Tom and Kemp, who were living in Los Angeles. Tom and Kemp Dawson boarded in the household of another family from Shreveport. In fact, during the 1930s and 1940s, Los Angeles was such a popular destination for migrants from Caddo Parish that one neighborhood earned the name “Little Shreveport.”113 Dawson’s family contributed to this migration pattern. His mother, two brothers, and other close relatives left Shreveport during this era and settled mainly in South Central Los Angeles, in Little Shreveport. After his discharge from the Army on March 28, 1946, Dawson returned to civilian life, earning a living as a barber and, once again, playing baseball.114

Within 10 days of his discharge, Dawson was the new catcher and occasional outfielder for the Pacific Pipe Lines, also known as the Pacific Pipe Line Colored Stars.115 The team boasted a lineup consisting of players with “professional experience with strong Negro teams.”116 One of his new teammates was a familiar face – center fielder and fellow Shreveport native Willie “Bill” Simms, who played with Dawson and the Monarchs in 1942.117 The Pipes were not exactly smoking up the semipro leagues. In his debut with his new team in early April, Dawson went 2-for-4 at the plate, but his efforts were for naught as the Rosabell Plumbers drained the Pipes, 11-2.118 Dawson continued to play for the Pipes through June, when they lost to the San Pedro Merchants in a twin bill described as being “of the nightmarish type with errors, wild pitches, bases on balls and mental lapses occurring as frequently as clowns at a three ring circus.”119 Despite the Pipes’ poor performance, Dawson enjoyed a bit of a personal revival. He was a regular in the lineup and swatted a respectable .286.120 By the end of June, however, the Pipes disbanded. A few months later, Dawson joined the Al-Leaverenz All Stars, a semipro team in the newly formed Orange Belt Winter Baseball League.121 The A.L. Leaverenz Paving Company of Monrovia, California, sponsored the team; its name also appeared as Leverenz or Al-Leverenz.122

Dawson was a catcher and occasional outfielder for the Al-Leaverenz All Stars for two seasons. Many of his teammates were Negro League veterans including his manager, Nathaniel “Nate” Moreland, a former pitcher for the Monarchs and the Baltimore Elite Giants.123 But the sun was setting on Dawson’s baseball days. After the 1947 season ended for the All Stars, he married Lottie Mae Abner, a waitress, in Los Angeles, on October 15, 1947. The union did not last, and the couple had no children together.

Dawson’s career in semipro baseball effectively ended with his marriage. The Al-Leaverenz team folded before the 1948 season started and Dawson did not appear on the roster for other teams in the Orange Belt League. The only “Johnnie Dawson“ who continued to appear in the sports pages after 1947 was another Californian, Johnny Dawson, a notable amateur golf champion and professional golf-course designer.124

Little is known about Dawson’s personal life after this point, other than that he continued to live in the Los Angeles area until his death at the age of 69 on August 6, 1984. No death notices or obituaries appeared in any Los Angeles or Shreveport newspapers to mark his passing or the deaths of any of his immediate family members. Dawson died almost a year to the day after his brother Kemp Dawson died in San Francisco. His brother Tom died in 1976, one year after the death of their mother, Lucy Carter Dawson Niles. Johnnie Dawson is buried in Inglewood Park Cemetery in Inglewood, California, in a section devoted to military veterans. He is not the only member of the 1942 Kansas City Monarchs interred there. Monarchs third baseman Herb Souell, who died on July 12, 1978, rests with Dawson in the cemetery.

Sources

All Negro League statistics and records were taken from Seamheads.com unless otherwise indicated.

Ancestry.com was consulted for census, birth, death, marriage, military, and other public records.

Notes

1 “Old Homes of Greenwood Tell Story of Caddo Pioneers,” Times (Shreveport, Louisiana), December 13, 1925: 27.

2 “North and South Louisiana Share Awards to Negroes,” Shreveport Journal, October 25, 1923: 12; “Award Prizes to Negro Boys, Shreveport Times, November 7, 1926: 3; “Caddo Negroes Given Agricultural Awards,” Shreveport Journal, November 16, 1926: 16.

3 “Leasing Near Gulf Test Recorded,” Shreveport Times, September 24, 1936: 16; Henry Wiencek, “Bloody Caddo: Economic Change and Racial Continuity During Louisiana’s Oil Boom: 1896-1922,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association,” 60 (2019): 199-224.

4 Library of Congress, “About The Caucasian,” https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88064469/.

5 “3 Negroes Fined $100 for Having Untaxed Whiskey,” Shreveport Journal, January 15, 1935: 1.

6 Shreveport Journal, April 18, 1898: 4.

7 “Beaumont Blacks Open Season with Local Negro Club,” Shreveport Times, May 10, 1923: 8.

8 “Negro Teams in Baseball Game This Afternoon,” Shreveport Times, October 7, 1934: 16.

9 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994), 825.

10 “Hall of Fame to Honor Two Local Negro League Stars,” Shreveport Times, July 24, 1991: 3B.

11 “Shreveport Negro Baseball Team in 22d Straight Win,” Shreveport Journal, July 22, 1935: 10.

12 “Negro Girl May Pitch in Contest Against Tigers,” Shreveport Times, July 10, 1935: 11; “Tigers to Play Indians of Hope, Arkansas Sunday,” Shreveport Times, July 18, 1935: 10.

13 “Acme Giants Won 107 Contests on Tour This Season,” Shreveport Times, September 28, 1935: 14.

14 “Acme Giants Won 107 Contests on Tour This Season.”

15 “One Bad Inning Costs Tigers Game with Acme Giants,” Shreveport Times, April 6, 1936: 9.

16 “Monroe Monarchs Play Tigers Twin Bill Here Sunday,” Shreveport Times, June 20, 1936: 15; “No-Hit Contest Features Twin Win by Tigers,” Shreveport Times, July 13, 1936: 12.

17 “Shreveport Negro Team Wins Two,” Shreveport Journal, August 17, 1936: 8.

18 “Local Negro Nine Wins Ark-La-Tex Baseball Laurels,” Shreveport Times, September 21, 1936: 9.

19 “Colored Teams to Clash Here Tonight,” Daily Tribune (Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin), June 5, 1937: 5.

20 “Black Sports Will Play Kansas City,” Shreveport Journal, March 29, 1929: 21.

21 “Monarchs Defeat Shreveport Nine Before Big Crowd,” Shreveport Times, April 12, 1937: 9.

22 Douglas Flamming, Bound for Freedom: Black Los Angeles in Jim Crow America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 48.

23 “Ralph Ring, Farrell Rematched [sic],” Progress Bulletin (Pomona, California), May 15, 1940: 10.

24 Eddie West, “Rattled Referee Gives Nod to Mendez, Wrong Fighter,” Santa Ana (California) Register, April 17, 1937: 6.

25 “Rematches Top Amateur Card,” Los Angeles Times, August 29, 1937: 28.

26 “Tigers to Usher in Season Today Against Houston,” Shreveport Times, March 28, 1937: 19.

27 “Leading Negro Teams to Meet at Dixie Park,” Shreveport Times, April 11, 1937: 24.

28 “A’s Defeated in Opener, 2-1,” South Bend (Indiana) Tribune, May 26, 1937: 21; “Albion Tigers Win in 10th on Squeeze Play,” Wisconsin State Journal (Madison), June 1, 1937: 14.

29 “Colored Teams to Clash Here Tonight,” Wisconsin Rapids Daily Tribune, June 5, 1937: 5.

30 “Colored Teams to Clash Here Tonight.”

31 “Dark Boys Win and Lose to Cherries,” Chilliwack (British Columbia) Progress, July 7, 1937: 10.

32 “Sport Shots,” Chilliwack Progress, July 14, 1937: 10.

33 “Sport Shots.”

34 “Colored Giants to Play Laurel Team Thursday Evening,” Laurel (Montana) Lookout, July 28, 1937: 4.

35 “Gun Club Has Party,” Billings (Montana) Gazette, July 31, 1937: 10.

36 “Brews Will Meet Shreveport Team,” Post-Crescent (Appleton, Wisconsin), August 16, 1937: 16.

37 “Shreveport Tips Cambridge, 4-2,” Wisconsin State Journal, August 22, 1937: 9.

38 “Shreveport Tips Cambridge, 4-2.”

39 “Indies Win Two, Lose One Game Over Weekend,” Muscatine (Iowa) Journal, September 13, 1937: 6.

40 “Indies Win Two, Lose One Game Over Weekend.”

41 “Baseball,” Muscatine Journal, September 10, 1937: 10.

42 Riley, 222.

43 “Local Negro Nine Defeats Colored Big Loop Champs,” Shreveport Times, April 6, 1938: 12.

44 “Negroes to Open Season at League Park Here Sunday,” Shreveport Times, April 14, 1938: 13.

45 “Local Negro Club Will Put Spring Team in League,” Shreveport Times, April 15, 1938: 19.

46 “Giants Monarchs Split,” Chicago Tribune, August 1, 1938: 23.

47 “Colored Nine Gets 4 Runs in 1st Frame,” Daily Times (Davenport, Iowa), August 2, 1938: 12.

48 “Colored Nine Gets 4 Runs in 1st Frame.”

49 “Monarchs Win 6 to 1 Battle from All-Stars,” Quad City Times (Davenport, Iowa), August 2, 1938: 11.

50 “Two for the Monarchs,” Kansas City (Missouri) Times, August 15, 1938: 10

51 “Two for the Monarchs.”

52 “Second Half of League Race Ends in Dispute,” Chicago Defender, September 10, 1938: 8.

53 “Second Half of League Race Ends in Dispute.”

54 “Provide Fitting Setting for End of Ball Season in Lincoln, Nebr.,” Omaha Guide, September 24, 1938: 7; Riley, 255.

55 “Negro Teams Play for Southwest Baseball Title,” Shreveport Times, September 9, 1938: 14; “Galveston Negro Team Will Play Here Sunday,” Shreveport Times, September 16, 1938: 16.

56 “Famous Negro Baseball Team Be Here Soon,” Kilgore (Texas) News, April 30, 1939: 5; “Satchel Paige Brings All-Star Negro Nine Here,” Courier-Times (Tyler, Texas), April 30, 1939: 13; “Second Big-Time Negro Baseball Game Tuesday, News Messenger (Marshall, Texas), April 30, 1939: 5.

57 “Santop Honored in Cooperstown,” Morning Telegraph (Tyler, Texas), July 31, 2006: 23.

58 “Road Clubs in Action,” Star-Phoenix (Saskatoon, Saskatchewan), June 23, 1939: 15.

59 “Davidites Take Beating from Orleans Stars,” Calgary Herald, July 8, 1939: 7.

60 “Davidites Take Beating from Orleans Stars.”

61 “South Team for All-Star Negro Game Announced,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, September 28, 1939: 14.

62 “Road Clubs in Action,” Star-Phoenix, June 23, 1939: 15.

63 “Road Clubs in Action.”

64 Harry Levins, “Helen Stephens Dies at 75,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 18, 1994: 11-12.

65 “Jesse Owens to Compete Against Helen Stephens,” Cedar Rapids (Iowa) Gazette, August 17, 1939: 11: “Famous Girl Sprinter Billed at Parkway,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 31, 1939: 16.

66 “South Team for All-Star Negro Game Announced,” Times-Picayune, September 28, 1939: 14.

67 “South Team for All-Star Negro Game Announced.”

68 “North Swamps South in Negro Ball Game,” New Orleans States, October 2, 1939: 10.

69 “Chicago Has Big Inning,” Chicago Defender, May 11, 1940: 22; “Chicago, Memphis Divide,” Chicago Defender, May 11, 1940.

70 Cum Posey, “National Leaguers Dominate All-American,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 2, 1940: 17.

71 “Pirates Meet ’39 Negro Champs Tonight,” Red Bank (New Jersey) Daily Standard, August 6, 1940: 15.

72 Ron Avery, “A Soup Salutes Innard [sic] City,” Philadelphia Daily News, November 18, 1991: 6

73 “Pepper Martin May Be Traded, Hot Stovers Say,” Journal Times (Racine, Wisconsin), January 7, 1940: 7.

74 “Negro World Series Here,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Telegraph, September 11, 1940: 17.

75 “1941 Edition of the Memphis Red Sox,” Chicago Defender, June 7, 1941: 23.

76 “Negro Nines Divide Double Bill,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 9, 1941: 18.

77 Bob Overtaker, “Stars Defeat Studebakers by 1-0 Score,” South Bend Tribune, June 13, 1941: 1, 2.

78 Overtaker.

79 “Satch’s Team Splits with Clown Nine,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 21, 1941: 16.

80 “Ray T. Rocene, “Sports Jabs,” Missoulan (Missoula, Montana), June 22, 1941: 7; “Davids Annex First Game,” Billings Gazette, June 27, 1941: 10; “Davids Rally by Monarchs for Great Crowd,” Montana Standard (Butte), June 27, 1941: 10.

81 “Kansas City Monarchs Whitewash Eugene Athletics, 14-0,” Eugene (Oregon) Guard, July 15, 1941: 6.

82 Frank A. Young, “Bob Feller Joins Dean Game Against Paige,” Chicago Defender, May 23, 1942: 19.

83 “Kansas City Splits Even with Grays,” Chicago Defender, May 9, 1942: 21.

84 “Black Barons Split Double-Header with Kansas City Monarchs 12-2 and 5-4,” Weekly Review (Birmingham, Alabama), June 13, 1942: 7.

85 “Eighth Inning Miscue Gives Monarchs Unearned 7 to 5 Win,” Fremont (Ohio) News-Messenger, July 24, 1942: 9; “Monarchs Down Quaker Squad in Listless Battle,” Scranton Times-Tribune, August 1, 1942: 10.

86 “A Day for Satchel Paige,” Kansas City Star, July 27, 1942: 8.

87 “A Day for Satchel Paige.”

88 “Negro Tossers Play Here Tonight,” Harrisburg Evening News, August 12, 1942: 18; “Games Held Up,” Evening News, August 13, 1942: 18.

89 “New Catcher Will Show for Monarchs Tomorrow,” News-Press (St. Joseph, Missouri), August 23, 1942: 11; “Monarchs to Tangle with Loop Rivals Here Tonight,” St. Joseph (Missouri) Gazette, August 24, 1942: 7.

90 “New Catcher Will Show for Monarchs Tomorrow”; Riley, 671.

91 Riley, 671, 672; “Paige’s Catcher Robinson Is Full of Stories of his Place in History,” Asheville (North Carolina) Citizen-Times, July 5, 1996: 38.

92 “New Catcher Will Show for Monarchs Tomorrow.”

93 Riley, 671.

94 “Black Barons Clash with Cincinnati Club in Sunday Twin Bill,” Birmingham News, August 14, 1942: 20.

95 “Black Barons Ready for Season’s Final Tilt with All-Stars,” Birmingham News, October 4, 1942: 45.

96 “Black Barons vs. Cincinnati Buckeyes,” Weekly Review (Birmingham, Alabama), August 15, 1942: 7.

97 “Birmingham Black Barons Trip Cincinnati 5-2, 3-0,” Jackson (Mississippi) Advocate, August 22, 1942: 8.

98 “Autos Humble Birmingham Black Barons by 8-2 Last Night,” News-Palladium (Benton Harbor, Michigan), August 27, 1942: 12.

99 “Ethiopian Clowns Trim Black Barons Twice,” Indianapolis Star, September 21, 1942: 18.

100 “Clowns Nose Out Back Barons, 6-5,” Illinois State Journal and Register (Springfield, Illinois), September 22, 1942: 10.

101 “Clowns Nose Out Back Barons, 6-5.”

102 Monarchs Lose,” St. Joseph Gazette, September 21, 1942: 5.

103 “Monarchs Lose.”

104 “Barons Defeat Two Opponents,” St. Joseph Gazette, September 23, 1942: 5.

105 Barons Defeat Two Opponents.”

106 Gene Sullivan, “Wise Owl,” St. Joseph News-Press, September 24, 1942: 15.

107 Sullivan.

108 “Barons Now Travel by Train as Bus Is Wrecked,” Birmingham News, September 26: 9.

109 “Black Barons Beat Major Leaguers, 6-3,” Birmingham News, October 5, 1942: 14.

110 “Negro American Loop All-Stars to Battle Black Barons Sunday,” Birmingham News, October 2, 1942: 28.

111 Jay Sims, “Round the Blocks,” Weekly Review (Birmingham), October 10, 1942: 7.

112 “Black Barons Beat Major Leaguers, 6-3.”

113 Douglas Flamming, Bound for Freedom: Black Los Angeles in Jim Crow America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 48.

114 State of California, Department of Public Health, Certificate of Registry of Marriage, October 16, 1947.

115 “Merchants Down Pacific Pipe 21-1,” News-Pilot (San Pedro, California), April 29, 1946: 10.

116 “Merchants to Face Strong Negro Nine,” News-Pilot, March 23, 1946: 8.

117 “Merchants Down Pacific Pipe 21-1.”

118 “Rosabell Wallops Pacific Pipe Line,” News-Star (Pasadena, California), April 7, 1946: 16.

119 “Merchants Triumph Twice, 11-10, 17-7,” News-Pilot, June 17, 1946: 5.

120 “Merchants to Face Soldiers, Negroes,” News-Pilot, May 29, 1946: 4.

121 “Merchants Enter Organ Belt Loop,” News-Pilot, October 11, 1946: 6.

122 “Monrovia Semipros Outhit Foe but Lose 4th Loop Tilt,” News-Post (Monrovia, California), December 23, 1946: 2.

123 Riley, 567.

124 Shav Glick, “Golfer and Course Builder Johnny Dawson Dies,” Los Angeles Times, January 22, 1986: 38.

Full Name

Johnnie Dawson

Born

November 8, 1915 at Shreveport, LA (USA)

Died

August 6, 1984 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.