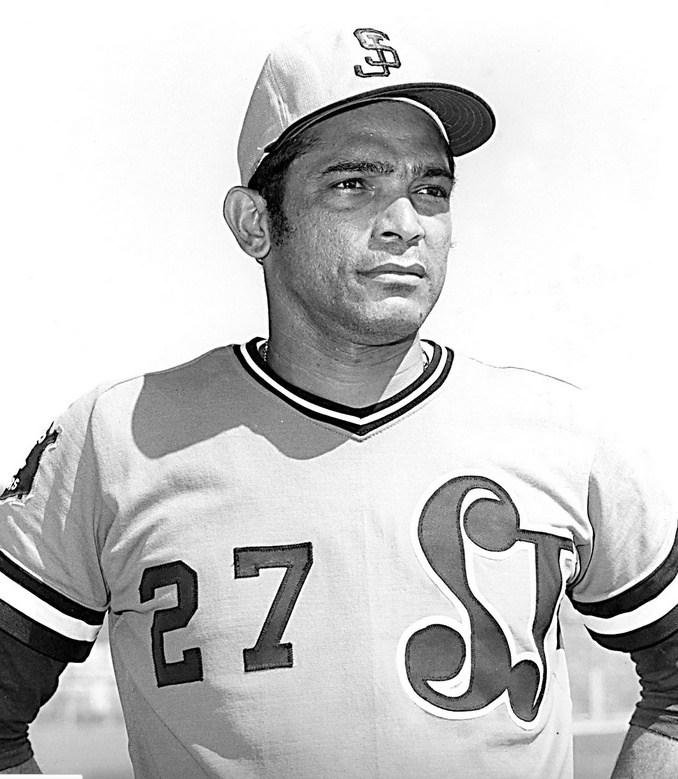

Julio Navarro

East of Puerto Rico lie the isles of Vieques and Culebra. Along with a sprinkling of cays, they are sometimes known as the Spanish Virgin Islands. As of 2018, pitcher Julio Navarro was the only viequense ever to make the majors, largely because the island is an undeveloped place with a population of only about 9,400 even today. The main reason is the controversial, now-vacated U.S. Navy training range that took up two-thirds of the land.

But what makes Navarro’s case more unusual is that he learned to play ball on St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands, where some of his relations continued to live. Navarro grew up with two major-leaguers born on St. Croix, Joe Christopher and Elmo Plaskett. He was about 11 years older than another, José Morales, but they became close friends. In another distinctive link, Morales stood godfather to Navarro’s son Jaime, a big-league pitcher from 1989 to 2000.

The elder Navarro appeared during six seasons in the majors (1962-66; 1970). However, his minor-league career spanned 20 years from 1955 to 1974, the last three in Mexico. He also played during 22 winters in Puerto Rico, tied for second in league history with Juan Beníquez, Juan Pizarro, and Héctor Valle. Only Rubén Gómez (29) played more. Navarro was known at home as El Látigo, or “Whiplash,” for his sidearm fastball.

Julio Navarro was the second of Manuel Navarro and Justina Ventura’s eight children (five boys and three girls). During his career and even in his obituaries, Navarro was said to have been born in 1936. However, his friend of several decades, Puerto Rican baseball man Luis Rodríguez Mayoral, revealed after Navarro’s death that the pitcher was actually born in 1934. He was yet another player who shaved a couple of years off his age for professional purposes.1 The 1940 census supports this, showing Julio to be 6 years old at that time.

In those days, two major plantation owners dominated Vieques: the Benítez family and Eastern Sugar Associates. Sugar cane was the crop, and most of the island’s residents worked in the fields. Since the second half of the 19th century, immigrants (many of African descent) had come from various other Caribbean islands to seek work, including St. Thomas and St. Croix.

Manuel was foreman of a crew of cane cutters. But in 1941 the Navy began to expropriate land on Vieques, plowing under the cane fields and forcing thousands to relocate. “When the sugar cane was torn out,” said Navarro in 2007, “my father went looking for a better job.” A wave of viequenses wound up in St. Croix. “We went there by boat — one of my sisters was born there.”2

Known as “Juju” growing up, Navarro went to St. Patrick’s, a Catholic school in Frederiksted. “I got a pretty good education for free, there were these Belgian sisters teaching.” The first sport he played was not hardball. “I used to play a lot of softball from ages 9-10, then when I got up around 14, I played baseball.”3

Navarro, Joe Christopher (who was about two years younger), and Elmo Plaskett (four and a half years younger) played at St. Patrick’s and also with a local club called the Annaly Athletics. That was a lot of talent for one little team, but the Virgin Islands overall were quite a wellspring in those days.

In 1954, the top Athletics and some players from St. Thomas joined the Christiansted Commandos to form an all-star squad. “There were four teams in the St. Croix amateur league: two from Christiansted and two from Frederiksted. The Athletics didn’t win the league that year, but then we put together this team and went to Kansas.”4

The Commandos traveled to that year’s National Baseball Congress World Series in Wichita. Navarro started one of their two NBC tournament games, while Joe Christopher caught the eye of Pittsburgh Pirates superscout Howie Haak. Christopher’s signing was a crucial event in Virgin Islands baseball history — it spurred Haak to add St. Croix and St. Thomas to his Caribbean itinerary. “They could see the talent in a lot of our guys. We spread the word — ‘they’ve got good guys, and they won’t cost you anything!’”5

In February 1955, Navarro played in a series between Puerto Rican winter leaguers and a combined Virgin Islands team. For many years this was an annual affair after the Puerto Rican season ended. Navarro impressed Alfonso Gerard, the pioneer pro ballplayer from the Virgin Islands. Gerard helped arrange a tryout in Puerto Rico with his boss, Santurce Cangrejeros owner Pedrín Zorrilla. Zorrilla was also a scout for the New York Giants.

Navarro worked out with Orlando Cepeda and José Pagán (whose path would cross or join Navarro’s often over the years). All three then signed with the Giants; Navarro got $300 while the others got $500.6 He reported to the Giants’ minor-league camp in Melbourne, Florida and was then assigned to Class D ball. Navarro’s ability to speak English also made him the de facto spokesperson for other Latino prospects in the organization. He helped keep them out of trouble.7

Navarro’s first year as a pro was not bright — his record in three leagues was a combined 1-10. “I hurt my arm a little, I had inflammation of the elbow. But they knew what I could do, so they didn’t release me. I didn’t go to college. I had to help my other brothers and sisters. I had two choices: pro ball or the Army. I went through a lot of hardship, but I just happened to make good.”8

In 1956, Navarro rebounded to win the Triple Crown of pitching with Cocoa in the Florida State League. He went 24-8 with a 2.16 ERA and 216 strikeouts. He thrived on work, starting 22 games and relieving in 27 others. “They kept me in Florida because of the weather. That was when the government was building up the rocket base at Cape Canaveral, right there by Cocoa Beach.”9

In between, Navarro made his debut in the Puerto Rican Winter League during the 1955-56 season. Pedrín Zorrilla added him to the Santurce roster, which included two veterans from St. Croix, Gerard and Valmy Thomas.

Navarro jumped to the Class A Eastern League in 1957. With the Springfield Giants, he went a respectable 9-9, 3.63, starting nine times in 45 appearances. He stayed at Springfield in 1958, but started in 30 out of 37 outings. His record was again solid (13-10, 3.07), but while he led the league in strikeouts again with 142, he walked over 100 batters for the third straight year.

A brilliant outset at Springfield in 1959 (6-0, 1.50 in seven starts) won Navarro promotion to Triple-A. Most encouraging was that he’d learned to throw strikes more consistently. With Phoenix in the Pacific Coast League, he shifted back to the bullpen once more, starting only once in 39 games (4-2, 4.38). He remained a swingman in both 1960 and 1961, starting 28 times amid 75 total appearances. The basic picture didn’t look good, with records of 5-12, 5.61 and 7-10, 4.81, but he showed enough to avoid demotion. Navarro remained in the PCL, but spent time on loan with Vancouver in the Orioles chain and also Hawaii, a Kansas City A’s affiliate.

“The Giants had so many prospects. They said, ‘Julio, you should play, but we don’t got no room!’” Navarro remembered that Elmo Plaskett made a brief two-game stop in Hawaii, but one of the stars on the Islanders was Puerto Rican comrade Carlos Bernier.10

Back with the Tacoma Giants in 1962, Navarro turned in easily his best Triple-A work. Manager Red Davis focused him on relief; starting just twice in 54 games, he went 8-9, 2.20. The Los Angeles Angels purchased his contract on September 2 for $30,000.11 “I was entitled to be a free agent, and so the Giants sold me. They couldn’t hold me any longer!”12

“Navarro was in the Giants’ farm system when I managed the club,” Angels manager Bill Rigney recalled in 1963. “But I didn’t see too much of him and only vaguely recalled him when our scouts came up with a favorable report on him.”13

The 28-year-old rookie — though he was thought to be 26 — made his debut the next day. It came on the biggest stage in the game, Yankee Stadium. L.A. sportswriter Braven Dyer (perhaps best remembered for being punched out by Navarro’s notorious teammate Bo Belinsky) noted that Navarro had never been to a major-league ballpark in his life before then.14 But there was a little more to the story than that. Navarro noted, “I had my chances before. But I made one promise to myself: I am only going to a big-league park when I myself am playing in it!”15

In the nightcap of a doubleheader, Navarro pitched three innings. He got off to an unsteady start, as Mickey Mantle greeted him with a single and then pulled off a double steal with Tom Tresh. A wild pitch was followed by two outs, a walk, and a single, and the Yankees extended their lead to 5-0. But Navarro settled down for two scoreless innings, catching Roger Maris looking for his first strikeout. The Angels later came back to win 6-5.

Navarro won his first major league game the following day with 1 1/3 scoreless innings against New York. Buck Rodgers gave him the lead with an RBI single in the top of the ninth, and though Tresh reached on a leadoff bunt single, Navarro then shut the door. He pitched in seven more games that month, including the last four innings of a 14-inning loss at Baltimore, and ended with a 4.70 ERA. In between, there was an interruption for a personal loss. Navarro returned to Puerto Rico because his 15-year-old brother Jaime had been killed in an auto accident.16

Navarro enjoyed his busiest and most successful year in the majors in 1963. He appeared in a club-high 57 games, all in relief, as he formed a reliable bullpen tandem with 40-year-old Art Fowler. His 4-0 start made him an early contender for Rookie of the Year, but while he finished with a 4-5 record, his ERA was a clean 2.89 and his 12 saves also led the team. Navarro said, “My control has been my saver. When I come in, I know I must throw strikes. I use a variety of pitches — sinker, slider, screwball, and fast ball. I throw mostly sidearm, but I come in overhand at times to fool the hitter. I like to work often.”17

Although Navarro was not especially tall for a major-league pitcher at 5’11”, he had “abnormally long arms, which makes his side-arm curve especially effective.”18 The screwball was something that Angels pitching coach Marv Grissom (who had pitched for Rigney with the Giants) added to his repertoire.19

The next year, Navarro got off to a quick start, combining with Ken McBride on an Opening Day one-hitter in Washington. President Lyndon Johnson threw out the first ball.20 However, the Angels traded him to Detroit on April 28 for outfielder-pitcher Willie Smith. After 10 shaky appearances (0-1, 10.22), the Tigers sent him down to Triple-A Syracuse at the end of May. He returned in early August, performing well enough to get his overall record back to 2-1, 3.95.

After that it was a struggle to return to the majors. Navarro did pitch in 15 games with Detroit in 1965 (0-2, 4.20, including his only big-league start on September 7). His only outing in 1966 was best forgotten. He failed to retire a batter on April 17, hitting Fred Valentine with a pitch, serving up a pinch-hit grand slam to Bob Chance, and then allowing a solo shot to Ken McMullen.

On June 21, Navarro was the player to be named later in a deal that smacked of racial injustice, as Boston unloaded Earl Wilson and old mate Joe Christopher. “When the Red Sox acquired two black players, pitcher John Wyatt and outfielder José Tartabull, on June 6 [actually June 13], Wilson told his black roommate, Lenny Green, that there were now too many black players [seven] on the ball club. Although the remark was made half in jest…to no one’s surprise, the phone rang the next morning.”21

Navarro also noted that when Charlie Dressen was the Tigers’ manager, the Latino players had a supporter. But a heart attack caused Dressen to step down as manager after 26 games in 1966 (he died that August). In Navarro’s view, the Hispanic Tigers then lost their backing in Detroit.22

Thereafter Navarro was mainly a serviceable Triple-A swingman. Boston sent him to Atlanta in December with pitcher Ed Rakow for Chris Cannizzaro and John Herrnstein. From 1966 through 1970, with Toronto and Richmond in the International League, Navarro’s record was 45-33, 3.44, as he started 84 times in 116 total games. He suffered a brief demotion to Double-A Shreveport in 1969 (5-1, 1.96).

Navarro surfaced for one last stretch in the majors with the Braves from July through September 1970. “They gave me the locker next to Hank Aaron, who’d played in Puerto Rico too. We had plenty to talk about.”23

With Atlanta, he posted no decisions and a 4.10 ERA in 17 games. (One rough outing came on August 1, when Bob Robertson, Willie Stargell, and his buddy José Pagán reached him for consecutive homers.) His last appearance, a 1-2-3 ninth inning at San Diego on September 9, left his big-league career mark at 7-9, 3.65 in 212 1/3 innings pitched over 130 games. He struck out 151, walked 70, and yielded 191 hits (including 32 homers) while picking up 17 saves.

By then 37, Navarro soldiered on for one more season with Richmond and Syracuse in the International League (7-13, 3.83). In March 1972, he was sold to the Mexico City Diablos Rojos, which at least one writer (Arnie Burdick in the Syracuse Herald-Journal) felt badly about. “If there’s anything wrong with the baseball pension system, it’s the failure to include the fringe player…Navarro, in his late 30’s, needs only three more big-league months, but was dealt by the Chiefs to the Mexican League 10 days ago. His chances of making the ‘bigs’ again are now infinitesimal, and his pension will add up to a big, fat zero.”24

Indeed, Navarro was one of many major-leaguers who were frozen out. “When I first went up to the bigs, you had to have five years to qualify. Then they brought it down to four. Then in 1985, they brought it down to one day. But I was before that. There’s a lot of money in the game now…and a lot of politics. People like [U.S. Congressman, later Senator] Jim Bunning and Brooks Robinson, they were trying to help us, me and about 1,000 other ballplayers. And some guys in California were fighting. It hasn’t changed yet.”

“I could use that money too. But God has been good to me.”25

Navarro spent two seasons with the Red Devils and split his last between Mexico City and the Córdoba Cafeteros. His 1972 record was a nifty 16-7, 2.29. He remained effective the next year (9-9, 2.77), as Mexico City won the league championship, but tailed off in 1974 (3-7, 4.92). The champion squad also featured at least five other former or future major-leaguers. The staff ace was Pedro Ramos (Cuba); Mexicans Enrique Romo and Aurelio López were also pitching mainstays; Ricardo Joseph (Dominican Republic) and Adolfo Phillips (Panama) were regular players. “They did have a pretty fair league there,” Navarro commented. But like nearly everyone who’s played south of the border, he remembered the endless bus rides. “Those roads were not the best, and from Mexico City to the Yucatán, that took 28 hours.”26

After that, El Látigo pitched on during the winters in Puerto Rico. As a young hurler, he had benefited from the tutelage of Santurce teammates Rubén Gómez and Bill Greason. Before the 1959-60 season, the Caguas Criollos sent Juan Pizarro and $10,000 to the Crabbers for Navarro and José Pagán. “This transaction was made subject to approval by the Braves and Giants. Much to the relief of Caguas and Santurce and Santurce, neither big-league organization objected to the deal. Caguas president Juan Vázquez was happy, because Navarro had been a nemesis of the Criollos.”27

One memorable game came on January 14, 1962, when Navarro pitched the only no-hitter at San Juan’s old Sixto Escobar Stadium. He lost 1-0 on José Pagán’s eighth-inning throwing error in the opener of a twi-night doubleheader (both games were scheduled for seven innings). “There were doubts about it being a hit,” Navarro recalled. “The scorer first called it a hit, and changed his mind.”28

Navarro’s PRWL career peaked in 1967-68, when he went 10-1, 2.72 and helped lead Caguas to the league title after they finished second during the regular season. After 12 seasons with the Criollos, Navarro spent three with the San Juan Senadores. He was traded together with José Pagán for Cocó Laboy, Luis Alvarado, Iván de Jesús, and Sam Parrilla.29 All six boricuas played in the majors.

His final three campaigns came with the Bayamón Vaqueros, after he had stopped playing in Mexico. “‘When Pagán was appointed to manage Bayamón, he wanted me to continue pitching, but also had me coach the younger hurlers. John Candelaria was one of my major projects.’ Navarro recalls the tears of gratitude which flowed from Candelaria’s eyes after listening to one of his pep talks.”30 In addition to grooming the tall Nuyorican, Navarro also contributed on the mound, going 5-2, 1.41 as the Vaqueros captured the PRWL playoffs. Bayamón then went on to capture the Caribbean Series, held that year in San Juan.

Thomas Van Hyning, who chronicled Puerto Rican baseball in two books, noted how Navarro cherished the back-to-back championships won by the 1974-75 and 1975-76 Cowboys. In 1975-76, he had a 2.35 ERA and won a game in the finals against the favored Caguas team, who thought Navarro was too old to pitch well.31 That brought his total to five PRWL titles; he had also been a champion with Santurce in 1958-59 and Caguas in 1959-60.

Navarro finally retired at age 43 after 16 more games in 1976-77. He finished with career totals in the PRWL of 98 wins, 84 losses, and a 2.94 ERA in 1,623 innings pitched across 368 games. He struck out 994, walked 467, and threw 19 shutouts. He is among the league’s lifetime leaders in games pitched (second), strikeouts (third), wins (sixth), and ERA (eighth).

Navarro said that after his playing career ended, “I was a scout for the Cubs for a couple of years. Then I was a rookie-league coach with the Braves for about four years, then I was with the Indians for several years. Then I said it’s about time I get home and stay home. My kids were growing up, I had paid for my house and nobody could put us out of it.”32

“I did my saving, I had a small pension from coaching, and Jaime helped me and his mother out. We made it all right.”33 Jaime Navarro started making seven-digit salaries in 1993. One memorable episode came that season, when Jaime — big and talented, but prone to dreadful slumps — sought his father’s counsel. Cleveland in particular was feasting on him, and the reason? “Uncle José” Morales, then the Indians hitting coach, could tell that Jaime was tipping his pitches. Since he worked for Cleveland, he kept his mouth shut and watched his godson get pounded. Only after Morales left the club did he tell the secret.”34

When Elmo Plaskett passed away in 1998, Navarro lost his main source of news about life on St. Croix, though “Shady” Morales helped keep him in touch. In 1999, he said, “I have a lot of good friends there, and I love the people.” But he had some choice words for the powers-that-be and how they had let baseball languish. 35

In his heart, Julio Navarro remained a Puerto Rican. He was happily married to Ana Haydee Cintrón — known also by her middle name to those close to her — since February 15, 1958. In addition to Jaime, they had another son (Julio Jr.) and two daughters (Sonia and Samaydi). They lived in Bayamón for decades and a baseball field there is named for him.

Navarro remained a well-loved member of the Puerto Rican sporting community and continued to make public appearances. In November 2005, he joined many local greats, including Orlando Cepeda, as the city of San Juan celebrated the centennial of Pedrín Zorrilla’s birthday. In October 2006, it was Navarro’s turn; he and nine other athletes became members of El Pabellón de la Fama del Deporte Puertorriqueño (the Puerto Rican Sports Hall of Fame).

When interviewed in 1999 and 2007, this old athlete remained fit and healthy. Aside from gray hair, one of his few concessions to age was a pair of big square eyeglasses. “I don’t travel too much,” he said in 2007, “except to Orlando to see my kids. We just spent a month and a half around Christmas. Jaime spent the past three years pitching in Italy, and he gave me and Ana a trip there as an anniversary present. But only she went! I like to stay at home. Sometimes I put on clinics for the kids, even for some colleges, for free. It doesn’t matter what age, anybody who has a kid and asks for help — I love doing that, it keeps me happy!”36

As late as 2011, Navarro was still offering advice to hurlers. Fellow Puerto Rican Javier Vázquez had suffered a poor season in 2010, but after Navarro counseled him that winter to make up for loss of velocity with ball movement, Vázquez lowered his ERA from 5.32 to 3.69.37

Not long after that, Alzheimer’s disease set in, but as of 2016, Navarro was still at home, in his wife’s loving care. He exercised and remained capable of travel to Orlando. There he got together with José Morales, who also made his home in that area. Ana noted with a laugh, “They fall back into that St. Croix island patois.”38 Other Puerto Rican vets, led by Benny Ayala of the Baseball Assistance Team, visited Navarro to bring cheer.

On January 24, 2018, Navarro died in Orlando — where he had moved to receive better medical care — from complications of Alzheimer’s. He was 84. With him at the end, along with family, was José Morales. The news came from Luis Rodríguez Mayoral, who viewed Julio and Ana as a second set of parents. His Facebook announcement was subsequently picked up by Puerto Rican newspapers.39

Julio Navarro was laid to rest in Bayamón’s Cementerio Los Cipreses. He was an exceptionally gracious man who was content in life and with the many good friends he had made. A conversation with him typically ended with his sincere wish, “Qué Dios te bendiga” — God bless you.

An earlier version of this biography was included in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Julio Navarro for his personal memories (telephone interview on March 9, 2007) and to Ana Cintrón de Navarro for an update (telephone interview on June 17, 2016), as well as Luis Rodríguez Mayoral (e-mail and telephone interview, January 27, 2018).

Sources

Books

José A. Crescioni Benítez, El Béisbol Profesional Boricua (San Juan, Puerto Rico: Aurora Comunicación Integral, Inc., 1997), 336.

Pedro Treto Cisneros, editor, Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano, 11th edition. Mexico City: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V., 2011.

Online

Ancestry.com

Notes

1 Telephone interview, Luis Rodríguez Mayoral with Rory Costello, January 27, 2018 (hereafter 2007 Rodríguez Mayoral interview).

2 Telephone interview, Julio Navarro with Rory Costello, March 9, 2007 (hereafter 2007 Navarro interview).

3 2007 Navarro interview

4 2007 Navarro interview

5 2007 Navarro interview

6 Thomas E. Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1995), 125.

7 Nick Diunte, “Julio Navarro, pitched 22 seasons in Puerto Rico, dies at 82,” Baseballhappenings.net, January 26, 2018.

8 2007 Navarro interview

9 2007 Navarro interview

10 2007 Navarro interview

11 “Angels’ Julio Navarro More Proof Island Pitchers Tops”, Chicago Daily Defender, June 25, 1963, 24.

12 2007 Navarro interview

13 Al Wolf, “Julio Navarro Finally Arrives”, Los Angeles Times, June 25, 1963, C2.

14 Braven Dyer, “Navarro Fits in With Best Angel Tradition”, Los Angeles Times, September 6, 1962, B2.

15 2007 Navarro interview

16 “Tragedy Calls Hurler Home”, New York Times, September 11, 1962, 37.

17 Joe Hendrickson, “Giants May Wish for Navarro”, Pasadena Star-News, May 30, 1963, 22-23.

18 Dyer, op. cit.

19 “Angels Blank Senators; McBride, Navarro Combine On One-Hitter,” Chicago Daily Defender, April 14, 1964, 22.

20 Ibid.

21 Larry Moffi & Jonathan Kronstadt, Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers 1947-1959 (Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press, 1994), 226, 166.

22 Diunte, “Julio Navarro, pitched 22 seasons in Puerto Rico, dies at 82.”

23 2007 Navarro interview

24 Arnie Burdick, “Players not apt to find sympathy,” Syracuse Herald-Journal, April 3, 1972, 15.

25 2007 Navarro interview.

26 2007 Navarro interview.

27 Van Hyning, 125.

28 Van Hyning, 220.

29 Van Hyning, 125.

30 Ibid.

31 Van Hyning, 126.

32 2007 Navarro interview.

33 2007 Navarro interview.

34 Mel Antonen, “Navarro’s Godfather Doesn’t Pitch Advice,” USA Today, March 11, 1994, 4C.

35 In-person interview, Julio Navarro with Rory Costello, February 1999.

36 2007 Navarro interview.

37 Diunte, “Julio Navarro, pitched 22 seasons in Puerto Rico, dies at 82.”

38 Telephone interview, Ana Cintrón de Navarro with Rory Costello, June 17, 2016.

39 Luis Rodríguez Mayoral, Facebook post, January 25, 2018. E-mail from Luis Rodríguez Mayoral to Rory Costello, January 27, 2018. “Fallece el exlanzador de las Grandes Ligas, Julio Navarro ,” Primera Hora (Guaynabo, Puerto Rico), January 25, 2018. “De luto el béisbol puertorriqueño,” El Vocero (San Juan, Puerto Rico), January 25, 2018.

Full Name

Julio Navarro Ventura

Born

January 9, 1934 at Vieques, (P.R.)

Died

January 24, 2018 at Orlando, FL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.