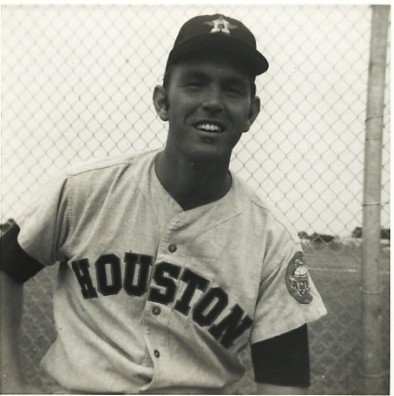

Keith Lampard

How many big-leaguers since World War II have been born in England? How many have appeared on Topps “Rookie Stars” cards in three separate years? The answers (as of 2020): seven in each category.[1] Keith Lampard, who played 62 games for the Houston Astros in 1969-70, claimed both odd distinctions.

How many big-leaguers since World War II have been born in England? How many have appeared on Topps “Rookie Stars” cards in three separate years? The answers (as of 2020): seven in each category.[1] Keith Lampard, who played 62 games for the Houston Astros in 1969-70, claimed both odd distinctions.

Christopher Keith Lampard was born in Warrington, England, on December 20, 1945. His parents, Gordon and Lillian (née Kenwright) Lampard, were British citizens. Gordon was born in Yorkshire; he played cricket and soccer before emigrating. During World War II he was in the Royal Navy, serving aboard an aircraft carrier. When he saw the city of Portland, Oregon, he liked it so much that the family moved there in 1949. Keith said in 2010, “The rain and the mist reminded him of home.” Indeed, Warrington (in Cheshire, about midway between Liverpool and Manchester) gets even more annual precipitation than drizzly Portland.

After coming to the United States, Gordon worked several jobs to support Lillian and their two children, including public school maintenance work. The family surname changed a bit; it rhymes with “hard” in England, but in America they went with the flow and let it rhyme with “leopard.” “Except for my sister Carol,” said Keith. “She stuck with the old way, like the soccer player Frank Lampard, my distant cousin.”

Keith — who went by his middle name ever since his first-grade teacher wanted to separate him from another boy called Christopher[2] — began to play baseball at the age of eight. A few years later, he made another short list. As of 2010, just 32 men have made it to the majors after appearing in the Little League World Series. Two of them represented the Rose City Little League of Portland in 1958: Lampard and pitcher Rick Wise. Typical of many youth stars, Keith both played the field and pitched, alternating starts with Wise.

In 2006, Lampard recalled that summer for the Portland Tribune. “In those days, there were only seven teams that made it, and it was single-elimination. We lost our first game 2-1 (to Kankakee, Ill.), and that was kind of a disappointment. I got a couple of hits, but I don’t remember a lot of details. I do remember the trip to Williamsport (Pa.) was sort of like heaven for a 12-year-old. And what was neat, a lot of the kids on that team stayed together and got to the Babe Ruth World Series and won a state high school championship at Madison.” He added, “Our coaches were sensitive [and] caring. And they taught us good baseball.”[3]

Baseball was the only sport Lampard played at James Madison High. During three years of varsity ball there, he was 14-0 as a pitcher and hit .380. He also played American Legion ball. In the fall of 1963, Keith went to the University of Oregon in Eugene. “Wise had a chance to sign,” he said in 1973, “but when we got out of high school I had been thinking about college and a lot of things. I didn’t really get the money I wanted so I decided to go on to school.”[4] His parents also wanted him to go and he received a full-ride scholarship.

The 6’2” lefty continued to pitch in college, as well as playing first base. After his freshman year at Oregon, the Eugene Register-Guard had mentioned that he might pitch in the Central Illinois League.[5] Instead, he played in the semipro Portland City League. In Lampard’s sophomore year, 1965, he blossomed as a pro prospect. In one doubleheader against the University of Washington, he pitched a four-hitter and homered in the opener, then homered again as a first baseman in the nightcap. The Spokane Sportsman-Review gushed, “Marvelous Keith Lampard continued to dazzle opponents with his multiple skills.”[6]

Although Keith pitched well, he was Oregon’s number-two starter. He excelled at bat, hitting .362 with 11 homers (then a school record) and 37 RBIs in 36 games. The Ducks’ record was 27-8-1; they came in second in the Northern Division of the AAWU.[7] The champ was Washington State, starring the battery of Danny Frisella and John Olerud Sr.

The Houston Astros selected Lampard in the second round of the June 1965 amateur draft, on the recommendation of scout Bill Wight. “I had a milkshake and burger with Bill Wight on the U of O campus,” said Keith in 2010, “and I realized that pro ball was a real possibility.” The bonus was estimated at $40,000, though neither Houston nor Keith revealed the exact amount then. While the Associated Press noted, “Lampard had said it would take a considerable sum to take him out of school,” another quote from the new pro was pithier: “I got enough.”[8]

Lampard signed as an outfielder and never took the mound in the pros, though he still played first base at times. As a prospect, he made steady progress through the Houston chain. He advanced more or less a level a year from 1965 through 1968, rising from rookie ball to the Astros’ Triple-A farm club, Oklahoma City. Lampard got his first Triple-A trial in 1966, when he started the year by tearing up the Western Carolinas League with Salisbury (15 homers and a .341 average in 57 games). One distinct memory of that year was “pinch-hitting against some guy named Nolan Ryan in my first plate appearance in the Western Carolinas League All-Star game.” Salisbury manager Walt Matthews said, “He has a picture swing — one of the best I’ve seen this year.” Matthews added that left field would be Keith’s best position; “neither [Lampard nor Danny Walton] has outstanding speed or super-strong arms, but they’re quick and can throw well enough to get the job done.”[9]

Keith was invited to spring training with the big club in 1968 and was not reassigned until late March. He faced heavy competition from many other young outfielders, however, including Bob Watson and Norm Miller. That year, the Astros even tried to make room by using Rusty Staub (whose legs had bothered him in 1967) mainly at first base. Lampard’s batting was just fair during the ’68 season (.266 average, 11 homers, 53 RBIs), and so he returned to Oklahoma City for another year of seasoning in 1969. Keith reported late to camp that spring because he was attending school. It didn’t slow him down. His 1969 season was impressive (.288-21-94) and merited a call-up in September.

Lampard made a splash with three hits in his first four big-league at-bats. In the fourth, on September 19 at the Astrodome, the rookie ended the game with a two-run pinch-hit homer off Cincinnati’s sidearm reliever, Wayne Granger. As one would expect, even more than 40 years later, Keith still clearly recalled his only home run in the majors. “It was what they call today a ‘walk-off.’ I was surprised to be chosen by manager Harry Walker to pinch hit. I remember watching Pete Rose and Bobby Tolan running towards the right field wall after hitting the second pitch off Granger in the Dome. Great thrill — almost ran over Jimmy Wynn rounding the bases.” It had to be a real shot, since the “Eighth Wonder of the World” had 390-foot power alleys and 16-foot fences then.

Jim Bouton, who was traded to the Astros late in the ’69 season, mentioned the blow in that day’s diary entry as he compiled his book Ball Four. He wrote, “I was happy for Lampard and could see he was having a lot of fun talking to the reporters.” Keith later returned the good feeling, saying, “I liked the book. . .I thought [it] really humanized the ballplayers — it showed them as real people, doing what real people do.”[10]

Lampard spent almost all of the 1970 season in Houston, except for a brief interval in June when he was optioned to Oklahoma City. Again he found the competition for playing time fierce. The Astros had Tommy Davis in left, but after promoting 19-year-old phenom César Cedeño in June, they traded Davis and moved Jim Wynn over to let the Dominican play center. In 2010, Keith said, “César Cedeño was a terrific talent and got the chance to be the star that he became for a few years. He could do it all, run, throw, hit, and hit with power. He really reminded you of a young Roberto Clemente.”

Lampard spent almost all of the 1970 season in Houston, except for a brief interval in June when he was optioned to Oklahoma City. Again he found the competition for playing time fierce. The Astros had Tommy Davis in left, but after promoting 19-year-old phenom César Cedeño in June, they traded Davis and moved Jim Wynn over to let the Dominican play center. In 2010, Keith said, “César Cedeño was a terrific talent and got the chance to be the star that he became for a few years. He could do it all, run, throw, hit, and hit with power. He really reminded you of a young Roberto Clemente.”

Jesús Alou and Norm Miller got most of the other outfield action for Houston in 1970, with César Gerónimo as the defensive spare. Lampard’s main role was pinch-hitting, which he did 43 times that year while starting just six games. He could have faced his old buddy Rick Wise at Philadelphia’s Connie Mack Stadium on June 16, but Wise left the game with a blister the inning before Keith entered.[11] “The first part of last season I felt like I was sitting around taking their money,” Lampard later told Eugene sportswriter Neil Cawood with a laugh. “But when I realized that’s what I’d be doing the rest of the season, I started to take the pinch-hitting more seriously.”[12]

That year, Keith became a disciple of Harry Walker’s spray-hitting approach. He said, “Harry got me leaning more on my front foot when I swung and it tended to level my swing out. Harry likes that kind of hitter — the slashing kind — especially in [the] Astrodome.”[13] A couple of years later, chatting again with Cawood, he said, “I didn’t play much and I sat around talking to Harry. He preached the Matty Alou style and I guess I kinda wanted to please him so I tried to hit that way.”[14]

In some ways it paid off. Though the Houston outfield was still full and he had to return to Oklahoma City, Lampard hit a career-high .337 in 1971. He was the MVP of the American Association’s All-Star game, another of his favorite memories. Yet he hit just 8 homers. Free-swinging slugger Donn Clendenon said that Walker tried to change his batting style too when they were with the Pirates in 1966, and he didn’t care for the advice. “It [the Walker stroke] takes away my value. He wants everybody to hit like him.”[15] That November, Keith was available in the major-league draft, and Montreal claimed him for $25,000.

When he got the news, he was playing in Venezuela, where the Astros sent many of their prospects for development. With Cardenales de Lara, he hit for good average but again with mild power (.272-3-17 in 55 games). “I played one year of winter ball in Barquisimeto [the capital of the state of Lara],” said Lampard in 2010. “I remember the bus rides along mountain roads, fires in the stands in Caracas, and shoes and other things being tossed on the field when the fans weren’t happy with the team. The Cardenales didn’t make the playoffs and we came home early.”

In spring training 1972, the Expos gave Lampard and veteran Tony González opportunities to win a job in the outfield. Neither made it. Early in camp, Montreal beat writer Ian MacDonald said, “Keith Lampard meets the ball solidly almost every plate appearance.”[16] Yet manager Gene Mauch said, “He’s tense as hell. I’ll have a talk with him and try to loosen him up.”[17] Later that month Keith was just 3 for 28, and MacDonald came down on his fielding and perceived lack of hustle.[18]

Under Rule V’s stipulation, the Expos could not farm Lampard out; they returned him to Houston for half the draft price. Back at Oklahoma City once more, Keith’s power production remained the same in 1972, but his average fell off to.257. The Houston organization sold him to Tulsa, the top farm club for St. Louis, in August.

In December 1972, St. Louis traded Keith to the Phillies for Byron Browne. It was a chance to go back home, because Philadelphia’s top farm club then was the Eugene Emeralds. In spring training 1973, batting instructor Wally Moses “erupted. . . ‘You’ve been around Harry Walker, haven’t you? That sonofagun hit .350 one year and led the league and knocked in 15 runs.’”[19] Moses was exaggerating, but the upshot was that Keith had to readjust.

“Now I’m back to this system,” he said that June. “If you have the strength and leverage the Phillies want you to stay on your back foot and take advantage of your power. Moses’ theory is the complete opposite of Walker’s and right now I think I’m kind of torn between the two.”[20]

That was Lampard’s last pro season. The organization made it clear to him that he was a backup player. Keith said, “I didn’t really like the idea, but Eugene is my home and I didn’t want to rock the boat.”[21] His production as outfielder and designated hitter was quite respectable (.307-12-54 in 88 games), but manager Jim Bunning was frank. The Emeralds turned over their roster, parting ways in one form or another with their top five home run hitters. In 1974, Bunning said, “None of these guys were major-league prospects. That’s why they were disposed of.”[22]

Lampard was prepared for life after baseball. He’d completed his undergraduate degree in social science at Oregon in March 1971, and he then studied for his master’s in health education, taking correspondence courses while on the road. “In some cities there’s not much to do so it’s a good time to do a little reading.”[23] Keith received his master’s in 1973 and went on to teach, coach, and be a public school administrator and counselor over the next 30 years.

Lampard married Sandra “Sandi” Engstrom, who was one year behind him at Madison High, in 1968. He was also married to Lanie Roberts from 1980 through 1993, and they had a daughter named Melinda. Subsequently, Keith and Sandi got remarried. They lived in the town of Neotsu on Oregon’s Pacific Coast, with llamas living on their acreage to “mow” the fields and entertain guests. Lampard coached baseball for several years after his playing days were over, but in 2010 he remarked, “beyond that I have really become an armchair fan of the game.”

In addition to the other favorite memories that Keith Lampard recounted here, what stood out for him during his baseball career was “being told by Oklahoma City manager Cot Deal that I would be going to Houston after the 89ers season in 1969. . .the respect and acceptance and help Joe Morgan showed to a mere rookie like me during my time in Houston. . .friendship with Bob and Carol Watson and their naming a son Keith after me. . .great teammates.”

Keith Lampard fell on the night of August 23, 2020, hitting his head. He remained unconscious afterwards. His situation was deemed inoperable because of the brain damage that had occurred – not so much from the injury but from the amount of internal bleeding as a result of the blood thinner in his system. He died on August 30. Lampard’s obituary in The Oregonian noted that in addition to being an animal lover, he was an avid golfer and woodworker. He also enjoyed helping people in his community. It ended by stating, “He will be remembered for his humility, warmth, kindness and generosity.”

Grateful acknowledgment to Keith Lampard for his memories (telephone interview, July 6, 2010; e-mail, July 12, 2010). and to Carol Lampard Stady (e-mail, October 29, 2020).

This biography was most recently updated on October 30, 2020.

Sources

Gordon Lampard obituary, Portland Oregonian, August 22, 2003.

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.goducks.com

www.checkoutmycards.com

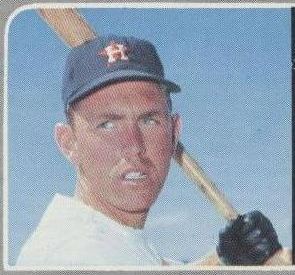

Photo Credit

The Topps Company (color photo)

[1] The count for England does not include other parts of the United Kingdom, i.e., Scotland (two: Bobby Thomson and Tom Waddell) and Northern Ireland (P.J. Conlon). The last big-leaguer born in Wales was Jimmy Austin, whose career ended in 1929. The “Rookie Stars” count is subject to further verification. Bill Davis almost certainly holds the record at five (1965-69). Lou Piniella (1964; 1968-69), Dave Dowling (1965-67), Pete Craig (1965-67), Marv Staehle (1965-66, 1969) and Bob Stinson (1970-72) also made three.

[2] The Lampard family emigrated to America aboard the famous Cunard liner RMS Caronia. The “Green Goddess” departed Southampton for New York on her maiden voyage on January 4, 1949. “Master Keith Lampard” (just past his third birthday) appeared on the passenger list, along with his parents and older sister Carol (http://www.caronia2.info/plc490104.php).

[3] Eggers, Kerry. “It’s a Brave new world for local scout.” Portland Tribune, August 22, 2006.

[4] Cawood, Neil. “Hanging tough.” Eugene Register-Guard, July 23, 1973: 3B.

[5] Strite, Dick. “Oregon Nine Must Rebuild.” Eugene Register-Guard, June 3, 1964: 1B.

[6] Price, Jim. “Cougars Can Testify: Pitching Pays.” Spokane Spokesman-Review, April 27, 1965:13.

[7] American Association of Western Universities, already known informally as the Pac-8, which would soon become the conference’s official name.

[8] “Houston Pays Bonus to Sign Lampard.” Associated Press, June 18, 1965. “Houston Signs Oregon’s Keith Lampard.” Eugene Register-Guard, June 17, 1965: 2D.

[9] Dupree, Ed. “Lampard and Walton Maul Western Carolinas Hurlers.” The Sporting News, June 18, 1966: 51.

[10] Cawood, Neil. “Ex-Duck Lampard wonders what Astros planning for him.” Eugene Register-Guard, February 7, 1971: 2B.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Cawood, “Hanging tough”

[15] Mann, Jack. “The Voice of the Pirates.” Sports Illustrated, September 5, 1966.

[16] MacDonald, Ian. “Morton signs; trade talk cools off.” Montreal Gazette. March 8, 1972: 10.

[17] MacDonald, Ian. “Expos’ notes: Bailey 0-for-5.” Montreal Gazette. March 13, 1972: 20.

[18] MacDonald, Ian. “Wine injury may alter Expos’ thinking.” Montreal Gazette. March 25, 1972: 15.

[19] Cawood, “Hanging tough”

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Gugger, John. “Bunning Fires Strikes.” Toledo Blade, June 10, 1974:

[23] Cawood, “Hanging tough”

Full Name

Christopher Keith Lampard

Born

December 20, 1945 at Warrington, Cheshire (United Kingdom)

Died

August 30, 2020 at Lincoln City, OR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.