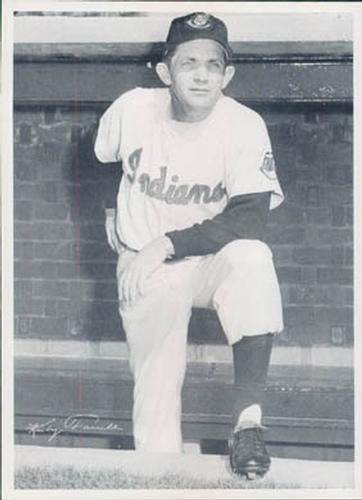

Kerby Farrell

Cleveland manager Kerby Farrell rushed to the mound after pitcher Herb Score was struck in the face by a line drive off the bat of the Yankees’ Gil McDougald on May 7, 1957. “He was bleeding from his eyes, nose, mouth and ears. All we could think of doing was trying to save his life,” Farrell recalled 10 years later.1

Cleveland manager Kerby Farrell rushed to the mound after pitcher Herb Score was struck in the face by a line drive off the bat of the Yankees’ Gil McDougald on May 7, 1957. “He was bleeding from his eyes, nose, mouth and ears. All we could think of doing was trying to save his life,” Farrell recalled 10 years later.1

The horrible injury that derailed Score’s career was the first of many unfortunate events that derailed Farrell’s one-year tenure as a major-league manager. Farrell played two years in the majors during World War II and had managed for more than 10 years in the minors when he got his chance to manage the Indians. Let go at the end of the season, he resumed one of Organized Baseball’s most successful minor-league managing careers.

Farrell is the only person selected three times as The Sporting News Minor League Manager of the Year, and the only manager to win the Junior World Series with a championship team from the International League and one from the American Association. His teams won five pennants, and he managed more than 3,150 minor-league games, winning 1,710 of them over 24 seasons.2

Major Kerby Farrell — “Major,” his first name, was a tribute to the surname of the man who had adopted Farrell’s orphaned father3 — was born on September 3, 1913, in Leapwood, Tennessee, about midway between Memphis and Nashville. His parents were Frank and Eula (Kerby) Farrell.4 Kerby was one of two children. His brother, Jasper, also played professionally. The family’s ancestry was a mix of Irish, Spanish, and Scottish. Farrell’s parents separated when Kerby was a child. His mother worked as a nurse.5

Kerby “started tossing a rubber ball against the side of the house from the time he could walk,” his mother said in a 1957 interview. “When he learned to read, he started poring over the sports pages.”6 He grew to an adult height of six feet even but never weighed more in his playing days than 172 pounds.

Farrell was graduated from Bethel Springs High School, not far from Leapwood, where he played basketball and baseball. For the next two years, he attended Freed-Hardeman Junior College in nearby Henderson, Tennessee. There, he played basketball on a scholarship (but didn’t play on the baseball team) and began courting the daughter of one of the college’s co-founders.7 A left-handed-throwing and -batting first baseman and pitcher, his play for semipro teams in Jackson, Gleason, and Henderson as was good enough that he was signed to a contract in 1931 by a scout from the Memphis Chicks.8

On a blistering hot day in August 1935, he and college girlfriend Mildred Nell Ledbetter, along with another couple, drove to Marion, Arkansas, where both couples got married in a hurry. The newlyweds then sped back to Memphis, where Kerby was due to play first base for the Chicks. “The game went 17 innings in extreme heat,” Nell recalled in 1957. “Kerby was pooped when it ended. The next day, he left with the Chicks on a 21-day trip, and I went to my office job as usual.” When the Memphis season ended, Kerby was off to Puerto Rico to play winter ball.9

Thus began a 40-year marriage that involved many moves from coast to coast as Kerby pursued his baseball career. Through it all, the couple’s offseason home was the house where Nell was born, next to the college in Henderson.10 When Nell Farrell was employed, she worked as a high-school librarian. In 1937 the Farrells had a child who died two days after his birth. After the war, the couple had two children, son Ben, born in 1946, and daughter Dixie, in 1947. Ben played minor-league baseball in the Phillies and White Sox systems.11

As a teenager, Farrell developed what would become a lifelong friendship with Lon Varnell. Varnell became the longtime basketball coach at Sewanee, the University of the South, and a promoter of concerts for Elvis Presley, Liberace, Elton John, and many other stars. Kerby’s son, Ben, succeeded Varnell, who died in 1991, as the head of Varnell Enterprises in Nashville, a major producer of concert tours and entertainment events.

By the late 1920s, Farrell and Varnell were playing for traveling baseball teams. In 1960, the two recalled a day when Varnell asked Farrell to accompany him to a game in Savannah, Tennessee. Farrell took a train to Adamsville, where Varnell lived, and they rode with their teammates in a truck until they reached a ferry crossing at the Tennessee River. The fare was $1 for the truck and 5 cents for each passenger. Short on cash, they left the truck and, after crossing the river, walked two miles into town in their baseball uniforms. Varnell recalled that the walk wasn’t so bad, but Farrell was appalled. Apparently it worked out; Farrell pitched and dealt the Savannah team its first loss of the season.12

Farrell and Varnell each later began officiating scholastic and college basketball games. Farrell continued officiating into the 1960s, mostly at the high-school level.13 Both men were inducted into the Tennessee and the Freed-Hardeman sports halls of fame. The two, both born in 1913, were classmates at the college.

Farrell began his professional career in 1932 as an 18-year-old, playing in 20 games at first base for Vicksburg/Jackson, Tennessee, in the Class D Cotton States League. The next season, as a 19-year-old, he played in 131 games for Beckley, West Virginia, in the Class C Middle Atlantic League, scored 100 runs and led the league’s first basemen in fielding. He appeared in 119 games at firstbase, and also pitched in 11 games, tossing 83 innings. His record was 5-5 with a 3.90 earned-run average.

He bounced around several levels over the next five seasons, at Tyler, Texas, in the Class C West Dixie League in 1934, then two seasons with Memphis in the Class A Southern Association, where he hit .286 in 146 games in 1936. Farrell took a step back to Greenville in the Cotton States League, which had moved up to Class C, the next two years. He had one of his best offensive seasons there in 1938, leading the league in hits, triples, and at-bats while scoring 109 runs and batting .311. He played in 47 games at Scranton in the Class A Eastern League in ’39 before returning to the Middle Atlantic League with Canton, where he had two solid seasons, hitting .297 and .288, leading the league in fielding percentage in 1940.

As a 27-year-old with Erie in the Middle Atlantic League in 1941, Farrell got his first chance to manage. His Erie team finished a strong second, and Farrell inserted himself as a pitcher in 10 games, the first time he had taken the mound professionally since 1933. His mound results in 51 innings that season were mediocre, but the next season, he was 7-1 in 18 games over 93 innings with an ERA of 2.61 – by far his best year as a pitcher. Overall in 1942, he appeared in 129 games, but his batting average fell 41 points, from .317 to .276. As a manager, his team slipped to fourth with a 63-65 record.

Stripped of players by World War II, the Middle Atlantic League shut down after the 1942 season. With the majors facing the same player shortage, Farrell – at 29 and married too old for the draft that season – got a call from the Boston Braves, managed by Casey Stengel. Farrell was signed in late March 1943.

“Casey brought me all the way from Class C to the majors.” Farrell told Roy Terrell for a Sports Illustrated feature in April 1957. “He said, ‘I don’t know where you’ll play but you’ll be up here all year.’ And I was.” So he and Nell found a place to stay in Boston.

Farrell paid a price for Stengel’s gesture, however. Hitting grounders to the infielders early in the season, Stengel hit a bouncer that smashed Farrell’s face and nose. Failing to play a bad hop was an aberration for Farrell, who always was a strong fielder. He didn’t have the facial bones properly set at the time and for the next 17 years lived with a flattened nose that left him with a raspy voice, headaches, and sinus problems. He finally had surgery to get it fixed in October 1960.14

“I could run and I could throw, but I never was a major league hitter – and I knew it. But I … had managed before I got up there, so I spent a lot of time looking around and watching and learning,” he told Terrell in 1957.

He performed adequately against the diluted National League talent in 1943, hitting .268 in 85 games. He even pitched 23 innings in five appearances, all in relief, losing his only decision. Still, the Braves decided he wasn’t needed in 1944, so Farrell spent the year with the team’s top farm club, Indianapolis, just in case. Never much in the slugging department, he hit .293 with just two homers. He pitched in six games, but his 6.95 ERA for 22 innings was by far the worst of his sporadic pitching career.

Before the 1945 season began, the Braves sold Farrell to White Sox, who were desperate for help at first base. He played in 103 games and had 102 hits, so he didn’t embarrass himself. He hit .258 in 426 plate appearances. His fielding percentage for his two big-league seasons was .992.

With major leaguers returning from the war in 1946, the White Sox sent Farrell to Little Rock in the Southern Association. He played most days at first and for the first time in four years did no pitching. He hit .294, respectable for a 32-year-old competing against much younger players back from the military.

In a wild 19-inning game (the first of a doubleheader, no less) on July 17, 1946, at Little Rock, Farrell had eight consecutive hits. That would have been the league record, except that teammate Lew Flick had nine hits in a row in the same game. Farrell had two more hits in the nightcap, finishing the day 10-for-13.15

That fall, the White Sox released Farrell so he could take a job as a player-manager in the Cleveland system. At Class B Spartanburg (Tri-State League) in 1947, his team won the pennant. He made a strong contribution as a player to that first-place finish: He led first basemen in fielding and hit .295 with a career-high 83 runs batted. In seven appearances on the mound, he posted a 1.93 ERA in 28 innings. Before the season’s final home game, the local Elks held Kerby Farrell Night, which drew a season-high crowd of 4,821. Farrell was presented with cash and gifts worth $750.

The 1948 season at Spartanburg was Farrell’s last as a regular player. He hit .286 in 121 games, nine of them as a pitcher. In ’49, he limited himself to 28 games in the field and nine on the mound. At 35, Farrell showed he could still pitch: He posted a 2.57 ERA in 35 innings.

Assigned to Cedar Rapids, Iowa, after the 1950 season, he and Nell traveled to a winter welcoming banquet attended by 230 people, with the outdoor temperatures a balmy 20 degrees Fahrenheit – below zero.16

In 1951 in the Class B Three-I League, Farrell played in just 19 games, three of them as a pitcher. On that team was a young pitcher who had signed for a $70,000 bonus. He had been sent to Cedar Rapids to work on his control. The first time the youngster started, he walked seven batters in a row. Farrell was so frustrated that he took the mound himself in relief and ended up pitching the rest of the game – and winning.17 It would be his last decision as a pitcher. Two relief appearances later in the season were his last on the mound.

Farrell continued to throw batting practice to his minor-league teams, however, especially when they were about to face a left-handed starter. He had another skill that stood out during drills: Despite being a natural left-handed batter, Farrell was an outstanding fungo hitter batting right-handed,18 which explains why he wrote “both” about how he batted when answering questions on a personal data form he filled out and signed when he was managing Buffalo in 1960. (The form is in his Hall of Fame Library clipping file.)

In 1952 at Class A Reading, Farrell appeared in12 games, a few of them at first base. In one of those games, after flailing and bailing at three pitches from young Ryne Duren, a wild, hard-throwing right-hander with poor eyesight, Farrell came back to the bench and told his team he was done as a player.19

In the Eastern League in 1953, Farrell’s Reading team won 101 games, which earned him a promotion to the Indians’ top farm team in Indianapolis. There, he won another pennant and his first award as the top minor-league manager.

Indianapolis became the second town to give him a Kerby Farrell Night, this one to mark his 41st birthday as his team was running away with the American Association pennant. Farrell got 10 cents from every ticket sold. The gate likely was inflated by the presence of young fireballer Score on the mound for Farrell’s squad.

The Triple-A Indians slipped to 67 wins in 1955 after 95 the previous year. In 1956, however, The Sporting News named Farrell Minor League Manager of the Year a second time when he led Indianapolis to a come-from-behind first-place finish over a strong Denver Bears team that featured several future New York Yankees. Indianapolis, behind the strong play of Roger Maris, went on to defeat Toronto, the International League champs, in the Junior World Series.

By this time, Farrell had gained an on-the-field nickname: “Shaky,” because of the way he quivered all over when he got into hated arguments with umpires.20

At the end of the ’56 season, Al Lopez resigned as Cleveland’s manager to take the same job with the White Sox. Farrell was an obvious candidate for the vacancy and made it plain that he wanted the job. Indians general manager Hank Greenberg, however, wanted to give it to Leo Durocher. But Leo the Lip was content to remain as a broadcaster at that point.

As Greenberg weighed his decision, the Cleveland newspapers went on strike. Anxious to get as much publicity as he could when he introduced the new manager, Greenberg held off an announcement. Farrell, meanwhile, was quite literally waiting by the telephone. Finally, on Thanksgiving morning, November 22, with the newspapers about to resume publishing after nearly a month, Greenberg called to offer Farrell the job. The pair appeared together at a dinner in Cleveland on November 28 to make it official.21

Always a proponent of the running game, Farrell promised that the 1957 Indians would have “dusty uniforms and torn pants from sliding.”22 He hired Eddie Stanky, an old friend, as his third-base coach. Farrell always demanded hustle and was a bit of a taskmaster, but younger players tended to appreciate his approach.

“Sometimes he really blows his top,” Score said. “He’d hold practice at midnight if he thought it would help.”23 Yet Score was a fan, having enjoyed great success playing for Farrell at Reading and Indianapolis. So was Rocky Colavito, who also followed Farrell from Reading to Indianapolis. “Sure, he gets excited, just like any other manager,” Colavito said in April 1957. “But he’ll work hard with you and he doesn’t play favorites.”24

“It’s a great feeling to know you helped a kid make the big leagues,” Farrell said in January 1975. “Throwing extra batting practice to Rocky Colavito and Roger Maris … cost me my arm, but it was worth it.25

Several of the Indians’ longtime stars were aging and injury-prone. Three pitchers who won 60 games in 1956 won just 22 in 1957. A 20-game winner in 1956, Bob Lemon had a variety of ailments before the discovery of bone chips in his elbow ended his season in August. He went 6-11 with a 4.60 earned-run average. A year later, his career was over. Early Wynn’s ERA jumped from 2.72 to 4.31. He fell to 14-17. Even so, he was the only Cleveland pitcher to make as many as 30 starts. Farrell was forced to use his ace relievers, Ray Narleski and Don Mossi, as starters. Both performed well enough, but left the bullpen weaker. In August, Narleski publicly criticized Farrell’s managing tactics.26

The cruelest blow clearly was the loss of Score, a lefty with Hall of Fame caliber potential. Farrell frequently recalled the details of the gruesome May 7 injury.

Looking at Score lying still on the mound, “I thought he was dead,” Farrell told Regis McAuley of the Tucson Daily Citizen in 1973. “But when I leaned over him, he said: “Kerb, have I lost my eye?” I put my arms around him and said, ‘No kid, you’re going to be all right.” Score did not pitch again that year, and although he claimed it wasn’t the injury that kept him from regaining his dominance, the lasting perception is that it did.

At one point in the season, Farrell said, he had just 16 players who weren’t suffering from some kind of injury. Promising rookie Maris had broken ribs. An arm injury ended pitching prospect Stan Pitula’s career. By June, an article in Sports Illustrated described the Indians as “the most injury plagued team in all of baseball.”27

The Indians limped to a sixth-place finish at 76-77, but attendance fell again, and the ax fell on Farrell. Greenberg told him before the last game of the season that he was being fired. Later in the offseason, Greenberg was fired, too.

“I worked hard for the Cleveland organization for 11 long years. Then they bounce me after one bad season,” Farrell said the next spring.28 “I am not looking for sympathy. I won’t deny that losing the Cleveland job was the biggest disappointment of my life.”29

Farrell wasted no time getting another managing job. The Phillies hired him to manage Triple-A Miami (International League) in 1958. Pitching for Miami that year was the ageless Satchel Paige, who proved exasperating to his hard-driving skipper. Paige was often absent until showing up to start every fifth day or for the late innings of a close game. A mere 51 years old that season, Paige went 10-10 with a 2.95 ERA for a team that finished 75-78.

In August, Paige was suspended for ignoring team rules, but the front office took responsibility for it. For his part, Farrell said Paige was always available when he needed him. In any case, the team’s sub-.500 finish cost Farrell his job. Not that it mattered much, because the Phillies ended their working agreement with the Marlins and began one with Buffalo, with Farrell as the new manager there in 1959.

Farrell made his one trip to manage in the Caribbean during the 1958-59 offseason, going to Venezuela to direct a winter-league team that won a championship. His other experience as a manager in the Caribbean was when his Buffalo Bisons visited the Sugar Kings in Havana in June 1959. Fidel and Raul Castro sat in the stands. Fidel decided to shut down professional baseball later that summer as part of his communist revolution.30

Taking over in Buffalo in 1959, Farrell led the Bisons to the IL pennant. Buffalo led the minors in attendance, to boot. Farrell was honored before the Bisons’ final home game with a Kerby Farrell Night – the third of his career. He was presented with a new Cadillac, driven onto the field by his old friend Lon Varnell.31

Farrell often helped Varnell in the offseason with promotions that included tours of the South by the Harlem Globetrotters. Farrell would coach the Chicago Brown Bombers, one of the teams that acted as foils for the Globetrotters’ antics during their usually one-sided games.32 He also coached teams organized to play the Harlem Magicians, owned by Varnell and competitors of the Globetrotters.33

After five seasons, Farrell was let go in Buffalo as attendance fell and the team finished out of the playoffs. New local management claimed to have consulted the Mets, for whom the Bisons were now the Triple-A affiliate, about the decision.34 The Mets director of player personnel was Stanky, who found a spot for his friend managing the team’s California League affiliate in Salinas in 1964.

Farrell was moved up to Double-A Williamsport in 1965. In late July, Wes Westrum replaced Stengel as Mets manager and bought in Walter “Sheriff” Robinson from Buffalo as a coach. Farrell returned to the Bisons for another stint as manager. In his first game back, Buffalo ended a nine-game losing streak. At season’s end, Farrell accepted the Mets’ offer to take over at Triple-A Jacksonville in 1966.

Then, in January 1966, he got a call from Stanky, now managing the White Sox. Stanky offered Farrell a job as a coach.35 Ready to get back to the majors any way he could, Farrell accepted. He managed the White Sox team in the Florida Instructional League in the 1967 and ’68 offseasons. Farrell remained a White Sox coach through 1969, even after Stanky was fired during the 1968 season, then returned to Cleveland to coach for Alvin Dark in 1970-71.

Qualifying for a major-league pension played a part in Farrell’s decision, according to Ben Farrell. “That pension was a big help when mom was in a nursing home,” he said.36

During the summer of 1966, his first year as White Sox coach, Farrell returned to Spartanburg for yet another ceremony in his honor, prior to a Western Carolinas League game. Fans there hadn’t forgotten his four years playing and managing the Peaches in the Tri-State League. More than 2,000 people attended.37

After the Indians fired Dark, Farrell was hired by the Minnesota Twins to manage Lynchburg in the Carolina League in 1972. The next year, he took over Triple-A Tacoma, the Twins’ Pacific Coast League affiliate. That would be his last managing job. He scouted for the Twins in 1974.

In the mid-1960s, Farrell had begun working in the offseason for the state of Tennessee, eventually as an assistant director at the Tennessee State Museum. In the spring of 1975, with no job in professional baseball for the first time in 44 years, Farrell volunteered to help coach Vanderbilt University’s baseball team. He still was hoping to land another managing job the following season.

Farrell always took losing so hard, his son Ben said, that the stress may have contributed to his death at age 62 of a massive heart attack on December 17, 1975. His father may have suffered a minor heart attack in 1971, according to Ben, but never told family members.

A summer league for college-age players in Nashville was re-christened the Kerby Farrell League after his death. It kept that name into the 1990s before becoming part of the national Stan Musial League.

“There are some who think it was a broken heart” that killed him, “brought about by the fact that he had no job in baseball and no expectation of one,” baseball historian and author Joe Overfield wrote in 1987.38

“I hate to be a loser,” Farrell said in March 1958 as he resumed managing in the minors after being fired in Cleveland. “If I ever quit, I’ll quit a winner.”39

He had mellowed a bit by the time he was inducted into the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame early in 1975. “I have had a rewarding career, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything,” Farrell said. “… Few people have been so lucky.”40

Farrell is buried at Woodlawn Memorial Park in Nashville. His wife, Nell, who died in 2000, is buried next to him.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Thomas Nester.

Notes

1 George Vass, “Mayhem on the Grass,” Baseball Digest, July 1966: 38.

2 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Kerby_Farrell. Baseball historian Joe Overfield in 1987 reported Farrell’s minor-league record as 1,736-1,532. No won-lost totals are reported for Farrell’s first five years as a manager on his main player page at Baseball-Reference.

3 Jep Cadou Jr., “Meet the Kerby Farrells,” Indianapolis Star magazine, April 25, 1954: 9.

4 McNairy County, Tennessee, Marriage Records 1861-1961 by Groom, 115. http://mcnairytnhistory.com/images/Grooms_A-L_Mar_1861-1961.pdf.

5 Telephone conversation with Ben Farrell, Kerby’s son, April 17, 2017.

6 Herman Eskew, “Man on a Hot Spot,” Nashville Tennessean magazine, June 30, 1957: 13.

7 Jim Schlemmer, “Tucson Honeymoon Has Nell Farrell Excited.” Akron Beacon Journal, February 17, 1957: 50.

8 Roy Terrell, “The Man Who Makes the Indians Run,” Sports Illustrated, April 8, 1957: 33.

9 Schlemmer, “Tucson Honeymoon.”

10 Ibid.

11 Conversation and email from Ben Farrell.

12 Raymond Johnson, “One Man’s Opinion,” column, Tennessean, Nashville, October 26, 1960: 16. Farrell recalled the date as being in July 1923, but given their ages at the time, this seems unlikely.

13 Conversation with Ben Farrell.

14 George Beahon, “In This Corner” column, Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, May 14, 1961: 29.

15 Bill Shirley, “Flick Hits Nine in Row, Marks Fall Like Flies in Long Dixie Tilt,” The Sporting News, July 31, 1946: 27.

16 Gus Schrader, “Warm Welcome to Farrell, Despite Sub-Zero Weather in Cedar Rapids,” The Sporting News, February 7, 1951: 18.

17 Raymond Johnson, “One Man’s Opinion” column, Tennessean, Nashville, February 7, 1969: 29.

18 Conversation with Ben Farrell.

19 Oscar Fraley (United Press), “Ryne Duren Made Farrell Retire as Player,” Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts), July 6, 1957: 14. This account was confirmed by Ben Farrell.

20 Baseball Register, 1957 Edition (St. Louis: C.C. Spink & Son), 248. Numerous newspaper stories also refer to this nickname.

21 Hal Lebovitz, “Hard Work Brings Reward for Farrell,” The Sporting News, December 5, 1956: 7.

22 United Press, “New Tribe Manager Wants Hustling Club,” Pittsburgh Press, November 29, 1956: 26.

23 Associated Press, “Kerby Farrell Considered Smiling Bulldog as a Pilot,” Appleton (Wisconsin) Post-Crescent, December 9, 1956: 33.

24 Terrell, “The Man Who Makes.”

25 Bud Burns, “Honor Well Deserved,” Tennessean, Nashville, January 26, 1975: 53.

26 “Narleski Cites Kerby ‘Theories,’” The Sporting News, July 24, 1957: 25.

27 Roy Terrell, “Gloom Here – Joy There,” Sports Illustrated, June 10, 1957: 16.

28 Joe Schabo, “Farrell Can’t Quit a Loser,” Fort Lauderdale (Florida) News, March 13, 1958: 35.

29 Milton Richman (United Press International), “Kerby Farrell Vows He ‘Will Come Back,’” Camden (New Jersey) Courier-Post, March 4, 1958: 16.

30 Conversation with Ben Farrell.

31 Joe Overfield, “Farrell a Major Part of Bison Past,” Buffalo Bison newsletter, June 1987: 9.

32 Johnson, “One Man’s Opinion,” Tennessean, Nashville, October 26, 1960. Ben Farrell said his father often “coached” the Washington Generals, another frequent foil of the Globetrotters. These early tours of the South by the Globetrotters, appearing before integrated audiences, were considered groundbreaking.

33 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, March 14, 1962: 32.

34 United Press International, “Farrell in Trouble With Bisons,” Allentown (Pennsylvania) Morning Call, September 5, 1963: 48.

35 Jerome Holtzman, “Ace Tutor Farrell Joins Stanky Staff,” The Sporting News, January 15, 1966: 9.

36 Conversation with Ben Farrell.

37 “Class A Highlights,” The Sporting News, August 6, 1966: 35.

38 Overfield, “Farrell a Major Part.”

39 Schabo, “Farrell Can’t Quit.”

40 Burns, “Honor Well Deserved.”

Full Name

Major Kerby Farrell

Born

September 3, 1913 at Leapwood, TN (USA)

Died

December 17, 1975 at Nashville, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.