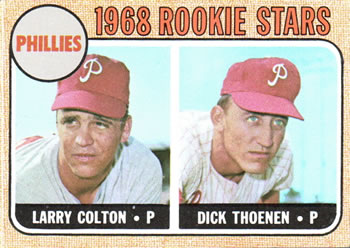

Larry Colton

For Larry Colton, one night in June 1968 seemingly devastated everything he had worked for. Just a few weeks after making his big-league pitching debut with the Philadelphia Phillies, a bar fight led to Colton’s shoulder separation, ending his time in The Show. During his one outing at the top level, he allowed one run in two innings of relief and faced two future Hall of Famers.

For Larry Colton, one night in June 1968 seemingly devastated everything he had worked for. Just a few weeks after making his big-league pitching debut with the Philadelphia Phillies, a bar fight led to Colton’s shoulder separation, ending his time in The Show. During his one outing at the top level, he allowed one run in two innings of relief and faced two future Hall of Famers.

Colton pitched on in the minors through 1970, with a brief comeback in 1975. However, he pursued a career of writing that earned him a Pulitzer Prize nomination, and his community work created a legacy of promoting literature and literacy.

Lawrence Robert Colton was born on June 8, 1942, in Westchester, California, a suburb of Los Angeles. His parents were Neldon Colton, an aerospace executive at Douglas Aircraft, and Hazel (née Storm). They had two children: Larry and Barbara, who was three years older than him.

In Westchester, Colton grew up an avid New York Yankees fan until the Dodgers moved to his home region. Colton and his dad even attended the first ever game the Dodgers played in L.A. in 1958.1 A right-handed pitcher and left-handed batter, Colton played in the Babe Ruth League and excelled on his Westchester High School baseball team. Larry also played basketball, averaging 19 points a game and getting recruited by numerous colleges, including John Wooden at UCLA.

Colton drew attention from both Dodger and Boston Red Sox scouts, but his father insisted on college. So, in 1960, Colton accepted a full-ride scholarship to play ball at the University of California, Berkeley. Teammates included future major leaguers Mike Epstein, Rich Nye, Dave Dowling, and Andy Messersmith. Another was Craig Morton, who eventually chose football over baseball and played quarterback in the 1971 and 1978 Super Bowls.2

Colton played freshman basketball at Cal. They had been to the Final Four two years in a row; he quickly learned that he didn’t have the game to make it at the major college level.

Colton initially played right field and shortstop for Cal, but he moved to pitcher in his junior year. In his collegiate pitching debut, Colton set a Cal strikeout record that still stands by ringing up 19 batters against UC Santa Barbara. He helped his own cause at the plate by hitting a home run.

Colton finished his junior year with a 4-2 record. Before his senior year, he dislocated his shoulder playing intramural football. He then went 7-7, and his stock as a prospect dropped. Still, Cincinnati Reds scout Ned Garver remarked that Colton was the “best young pitching prospect I’ve scouted [this] season.”3 That summer, Colton led his Culver City, California, team to the 1964 National Baseball Congress finals. Following the tournament, Colton signed with the Phillies as an amateur free agent on September 5, 1964. (The baseball draft didn’t begin until 1965.)

Colton returned to Cal in the fall of 1964 to take the remaining 12 credits he needed to graduate. There he met Denise Hedwig Loder, a sophomore art major from Beverly Hills and the daughter of Hollywood legend Hedy Lamarr. For Larry, it was love at first sight and their relationship took off.

Colton began his professional baseball career in the spring of 1965 with the Class A Eugene (Oregon) Emeralds. He won his first professional start and was 3-for-5 at the plate. But in April, President Lyndon Johnson began to ramp up the draft and Larry received notice that he was to report for duty on July 12. At the time, married men were exempt from the draft. So, although they had known each other for only four months, and three of them were spent living apart, Colton proposed to Denise on a visit she made to Eugene. She was 20, Colton was 23.

They were married on July 10 in Hollywood fashion — in Beverly Hills on Rodeo Drive. Documenting the wedding in his book Beautiful: The Life of Hedy Lamarr, Stephen Michael Shearer wrote: “The bride, her lush dark hair coiffed fashionably under a waist-length veil, wore a form-fitting white wedding dress with a long-sleeved lace bodice. She carried a bouquet of pale flowers. Her groom wore a white jacket, dark pants, and a bow tie.”4

The wedding was captured in the July 23, 1965 issue of Life Magazine with the headline, “Hedy Takes a Pitcher-in-Law,” along with the caption, “It was a posh wedding in Beverly Hills and former film star Hedy Lamarr, 53, looked as radiantly happy as she had at all six of her weddings.”5

Three days after his wedding, Colton beat the Yakima Braves 1-0, giving up only four hits. In fact, Colton won seven of the next eight starts he made as a newlywed, six of them in a row and three of them shutouts. By the end of his season with the Emeralds, though his won-lost record was just 12-10, Colton led the Northwest League in complete games (15) and finished second in ERA (2.89). He also hit .329 in 73 at-bats, often pinch hitting.

By this time, the Selective Service had changed the draft rules: married men were no longer exempt. Colton was scheduled to report to the US Army induction center in L.A. on December 1, 1965. The Phillies, like many other teams, were doing their best to get their players into active duty with the National Guard. But the day after Thanksgiving, Larry and Denise learned they were going to be parents.6Married men with children — or those with expectant wives — were still exempt. Larry wouldn’t need to report to the Army after all.

In 1966, Colton was the only player on the Eugene squad to be called up to join the 40-man big-league roster for spring training. Ultimately, he was sent to Macon (Georgia) in the Class AA Southern League. With Macon, Colton posted an 11-8 record and an ERA of 3.77 in 26 starts. During the season, Denise also gave birth to their daughter, Wendy Denise Colton.

Moving up again in 1967, to Class AAA San Diego, Colton started 31 games, which tied for the Pacific Coast League. He posted a 14-14 record with a 3.09 ERA, helping to lead his team to the PCL championship. During the winter of 1967, Colton played winter ball for the Ponce Leones in Puerto Rico, pitching against many great players such as Roberto Clemente and Orlando Cepeda. “I don’t know my final stats but at one time I was 6-1 with an era under 2.00,” said Colton. Counting spring training, the PCL, Florida Instruction League and Ponce, I pitched 400 innings that year…unheard of today. By the time I left Puerto Rico, I could barely lift my arm.”7

Going into the 1968 season, Colton was at the top of his game. But despite a strong camp, in which he gave up just four runs in 14 innings, manager Gene Mauch elected to send Colton back to San Diego. As a youth, Colton had seen Mauch play for the Los Angeles Angels of the PCL in the mid-1950s — and he remembered disliking “The Little General” as a player. Little did Colton know that someday Mauch would be his skipper and pull him from a game before he got a chance to swing the bat in the majors.

“I’d had a pretty good spring training,” Colton said. “I led the team in innings pitched. The press had anointed me as the heir apparent to future Hall-of-Famer Jim Bunning’s place in the rotation. But on the last day before breaking camp, Mauch summoned me to his office — in previous years he’d delegated the pitching coach to tell me I was being farmed out to the minors. This time, however, he was the one telling me I was being sent down. He said it was because there were a couple of off days during the first couple weeks of the season and they wanted me to get some innings in. ‘But we’ll call you back up in two weeks,’ he promised. I didn’t believe him. The minor leagues were filled with guys who’d been told that they’d be called right back to the big leagues and then vanished from the baseball ether.

“Because my wife and daughter were with me that spring in Florida, it didn’t make sense for them to go all the way to San Diego if I was going to Philadelphia in a couple of weeks. ‘Send her to Philadelphia,’ he said. So that’s what I did, taking him at his word. I pitched two games in San Diego giving up just a couple runs, and sure enough, ten days later the Phillies sent two excellent young prospects, Larry Hisle and Don Money, down and Roberto Pena and I were called up to the Phillies. My disappearance into the baseball ether had been delayed.”8

On April 26, he was brought up to Philadelphia from San Diego.

Colton made his major-league debut on May 6 against the Reds, wearing number 21 in front of a small crowd of 3,991 at Crosley Field in Cincinnati. “It was a chilly day. The crowd didn’t come out to watch two teams who were going nowhere. It was still early in the season,” stated Colton.9

The Reds had a solid lineup, including some key cogs in the Big Red Machine of the 1970s. With the Phillies down 6-1, Philadelphia manager Mauch put Colton in to start the bottom of the sixth inning. The first batter he faced was future all-time hits leader Pete Rose, who was working on a 20-game hitting streak. Rose doubled to center field on the third pitch.

Alex Johnson then grounded out to first and Rose took third. Four-time All-Star Vada Pinson then struck out on a slider. With two outs and Rose still on third, Colton then had to face a future Hall of Famer, Tony Perez, who grounded out. Colton’s first big-league inning was over.

“Yeah, Pete Rose was a tough way to start. The count was 2-0. I threw a fastball, and he drilled it and got a double. But he didn’t score. I finished my first inning with no runs and an ERA of zero.” Colton said.10

The Phillies failed to score in the top of the seventh inning. To start the bottom of the seventh, Colton gave up a leadoff double to Lee May. He then had to face another future Hall of Famer, Reds catcher Johnny Bench, who became NL Rookie of the Year that season. Colton got Bench to ground out to second. Next up was Tommy Helms, who blooped a single to left field, scoring May. Colton then retired the next two men.

Colton was due to lead off the top of the eighth inning, but Mauch sent up pinch-hitter Gary Sutherland. As a senior, Colton had given up a homer to Sutherland, an opponent at the University of Southern California. The two had lived together during spring training of 1966 to save money. Sutherland flied out to left field. The Phillies failed to score that inning, and the Reds went on to win,10-1.

Looking back, Colton said, “I wish Mauch didn’t pinch hit for me. We were behind something like 9-0. I’m a good hitter. In spring training that year, I got up 10 times and I got six hits.”11

“One of my favorite stories is that I saw Mauch several years later at a benefit event. I looked like Charlie Manson. He didn’t know who I was with beard and long hair. When I told him it was me, he said, ‘You could hit!’ My claim to fame is that I was a good-hitting pitcher.”12

After his debut in Cincinnati, Colton stayed with the big-league team. Although he often warmed up in the bullpen, and got a few “scares,” he never got the call from Mauch to pitch in another game.

“Mauch hesitated using rookies, especially rookie pitchers. And he still had the burden of ’64 when they blew a six-game lead with 10 games left,” said Colton.13

Then on June 4, after a game against the San Francisco Giants, Colton was out past curfew with a high school friend. His friend got in an argument with a couple of guys at the bar. Colton tried to break it up before any punches flew and he and his friend exited the bar. While he was waiting for his friend to get his car, the three men rushed out of the bar and jumped Colton from behind and sucker-punched him. His fall to the ground dislocated his left (non-pitching) shoulder. Two days later, Colton was placed on the disabled list for rehab. On July 6, he was sent to the Phillies’ San Diego farm team. And even though it wasn’t his pitching shoulder, the injury changed Colton’s mechanics and his fastball was never the same.

“I remember that night because it was the night Bobby Kennedy was shot,” said Colton. “I came out of the bar and there was a lot of confusion and anger in the streets and just before I got hit I remember thinking, is the world going insane?”

“Hey, I was in the wrong place at the wrong time,” he shrugged. “It just happened.”14

Following the fight, Colton’s baseball career began a slow, steady decline. After coming off the disabled list, Colton stayed at San Diego, playing in 15 games and going 5-7 with a 3.45 ERA. In the offseason, the Phillies moved their Class AAA team to Eugene. In 1969, Colton played in 26 games for the Emeralds, going 11-9 with a 4.18 ERA.

In January 1970, the Phillies sent Colton to the Chicago Cubs to complete a deal made the prior November. 17, 1969, when Johnny Callison went to the Cubs for Oscar Gamble and Dick Selma. Colton didn’t learn about it until he called the Phillies office to inquire about his contract. Dallas Green (then assistant farm director) told Colton that he had been traded a month earlier. When recounting this story, Colton wrote, “I was the ‘player to be told later’ too.”15

Colton spent the winter before the 1970 season on a rigorous training program so he could report to spring camp in top form. His weight dropped from 210 pounds to 180. But he got limited time in the Cactus League and was sent to Class AAA Tacoma (Washington) to be used in relief. Colton picked up two quick wins and a save, and manager Whitey Lockman moved him to the starting rotation. On May 16, Colton beat Salt Lake City 6-1, giving up only three hits — his second three-hitter in three starts. He also had a bases-loaded single in the eighth inning, which drove home the final two runs. At the 50-game mark, the team was 18-32, but Colton was 6-2 after starting the season in the bullpen.

In his comments to The Sporting News regarding Colton’s success, Lockman said, “First off, there’s his desire, his dedication — I can’t remember a player taking off 30 pounds, then keeping it off. Secondly, the discovery of his fast ball has a lot to do with his winning record. Last year he seemed content to be a ‘junkman’ but that’s changed now — he’s willing to challenge any batter in the league with his hummer.”16

Manager Leo Durocher and the big club were scheduled to visit Tacoma to play an exhibition on June 15, offering Colton another chance to prove himself in front of Cubs management. 17 But the day before the exhibition, Colton lost to the Hawaii Islanders 6-4, surrendering two home runs and four RBIs to pitcher Juan Pizarro. The Cubs bought Pizarro’s contract just a few weeks later in July. The success Colton had enjoyed that season started to slip away — he lost his next six games. His enthusiasm for the sport was also waning. By September, it became evident to Colton that at 28, the end of his pro career was near. After six seasons, he had only two innings in the majors to show for it.

Colton was scheduled to pitch one more game before the end of the season. It was in Spokane, Washington, against the division-leading Spokane Indians, who had a lead of 46 ½ games over last-place Tacoma. The Dodgers affiliate had a lineup including future big-league stars Steve Garvey, Bill Russell, Davey Lopes, and Bill Buckner, as well as Bobby Valentine, Tom Hutton, and Tom Paciorek. Future Dodger legend Tommy Lasorda was the manager.

In the May 25, 1981 issue of Sports Illustrated, Colton wrote an account of this final game. He started strongly with a few scoreless innings, but after he gave up four runs, Lockman pulled him in the bottom of the fifth inning with no outs. Colton walked off the field knowing his professional baseball career was over — at least for then.

During the 1970 season, Colton also encountered marital struggles. Later that year, he and Denise separated.

Faced with the reality of not going to spring training in 1971 — and with a daughter to support –Colton moved to Portland, Oregon, in the fall of 1970. There, through a friend’s recommendation, Colton started a teaching internship at Adams High School.

While living in Portland, he met Katherine (Kathi) Elisabeth Jeffcott. Soon after Colton’s divorce from Denise was finalized, he and Kathi were married. But budget cuts in Portland made finding a teaching job difficult, so they moved to Berkeley. However, the two moved back to Portland in 1973 and Colton secured a full-time teaching job. The same year, Colton’s second daughter, Sarah, was born. When school was out in the summers, he also painted houses.18

But in the summer of 1975, after a five-year absence, Colton got another chance to play professional baseball. Two years earlier, Bing Russell, actor Kurt Russell’s dad, had started a team in Portland. The Mavericks — chronicled in the 2014 documentary The Battered Bastards of Baseball — were a short-season Class A team in the Northwest League. Colton decided to try out.

“Every washed-up ball player came to tryouts figuring this was it,” Colton said. The Portland Mavericks could carry one player with higher than Class A experience. Colton made the team, despite what he calls his “Charlie Manson look” at the time. “Russell said to me at tryouts, ‘You sure can pitch, but you’re probably a druggie.’”19At 33, Colton was the oldest player on the team. He played for $400 a week and all the beer he could drink at Peter’s Inn, a local watering hole. 20

Unfortunately, Colton’s arm failed him; he was 0-2 with an ERA of 10.64 after his first three starts. Yet his batting was still good and he moved into the designated hitter slot. But two weeks into the season, the Mavericks got a call from Jim Bouton, who was looking to join the team. After the fallout from writing Ball Four, his best-selling tell-all about life in the big leagues, Bouton was also launching a comeback following five inactive years. The Mavericks chose to use their roster exemption to sign Bouton, releasing Colton even though he was batting cleanup and hitting .300.

Colton wrote a story about his two weeks with the Mavericks that made the front page of The Oregonian. The piece was well-received and he was soon writing regularly for The Willamette Week and other local publications. Six months after the article was printed, he quit teaching to write full time.

Colton’s first book, Idol Time, told the story of the Portland Trail Blazers’ 1976-77 championship season. In August 1977, Colton biked along the Oregon coast with the Blazers’ star, basketball Hall of Famer Bill Walton, as part of writing the book.

Colton’s marriage to Kathi ended in divorce in 1980. However, his writing career was taking off. He wrote over 250 articles for publications such as Esquire, Sports Illustrated, and The New York Times Sunday Magazine.

In 1985, faced with supporting his two daughters, Colton landed a corporate job outside of writing as a marketing projects manager at Nike — the athletic wear company headquartered near Portland. There he again applied his interest in sports and writing to produce promotional copy. The job had steady income and health benefits, but he hated it. However, at Nike Colton did also meet his third wife, Marcie.

In late 1987, Colton embarked on his second book, Goat Brothers, which chronicled the lives of himself and four Pi Kappa Alpha (Pi KA) fraternity brothers from their days at Cal in the 1960s to their middle age. The book was inspired by a conversation Colton had in 1979 with his long-time friend and Pi KA brother Steve Radich. Discussing the success of Sara Davidson’s 1977 best seller Loose Change — a book about three women from Cal and their life experiences from college in the 1960s through adulthood in the 1970s — Radich suggested that Colton should “write the male version.”21 Published in 1993, Goat Brothers became a main selection of the Book of the Month Club and was optioned for a movie.

In 1997, recognizing a need for higher literacy rates among local youth, Colton founded the Community of Writers, a Portland-area nonprofit that matches writers with local schools for age- and grade-appropriate workshops. The organization also offers a chance for teachers to take a 40-hour professional development course taught by published writers and receive four graduate-level college credits.

Three years later, Colton published his third book, Counting Coup. He spent 15 months living among Montana’s Crow Indians to follow the struggles of a talented and moody young woman named Sharon LaForge, a gifted basketball player. Upon its publication, Counting Coup received critical acclaim. It became the International eBook Foundation non-fiction book of the year for 2000 and garnered a Pulitzer Prize nomination.

In 2005 Colton co-founded the aptly-named Wordstock, a festival of books and writing in Portland. The event drew famous authors such as John Irving, Norman Mailer — and Jim Bouton. In a press release Colton stated, “Wordstock moves beyond the traditional book fair to create the best concentrated literary experience in the country — one that gives attendees a personal insight into literature from well-known authors as well as poets and successful Northwest writers. The Portland area is a community dedicated to culture and literature, which is important to make a festival like this a success.” In 2018, the event changed its name to The Portland Book Festival.

In 2010, he published his fourth book, No Ordinary Joes. The true story focuses on the early lives, World War II military service, and postwar experiences of four men captured by the Japanese from an American submarine in 1943. Until the end of the Pacific War, the four men remained captives, performing forced labor, undergoing physical torture, and managing to survive despite serious illnesses and near starvation.

Three years later, Colton’s fifth book, Southern League, was published. It documents the 1964 Birmingham Barons — the first integrated sports team in Alabama — as the Barons competed at the height of the civil rights protests. According to Colton, “It’s not only a baseball book, it’s really a story about segregation in America.” Colton had played in the Southern League in 1966 with Macon.

In 2013, The Portland Literacy Arts organization awarded Colton its Stewart H. Holbrook Literary Legacy Award. Katherine Dunn, the author of Geek Love, remarked that “the welfare of writers and the quality of teaching in the public schools have been central preoccupations in Colton’s life for more than 30 years.”22

Colton is currently writing two books and still lives in Portland. His two daughters live in the Pacific Northwest; he sees them often along with his three grandsons.

In 2015, he summed up his career with a film-related anecdote from an event hosted by the Portland Art Museum. “The assignment was to pick a movie scene that most speaks to you,” Colton explained. “I chose a scene from Field of Dreams where Ray Kinsella, played by Kevin Costner, goes out in search of Dr. Archibald ‘Moonlight’ Graham, whose professional baseball career lasted just one day. Kinsella asks Graham what it was like, to get so close to your dreams and not make it is something most people would think is a tragedy. Graham responds that it would have been a bigger tragedy if he’d only been a doctor for a day.

“I’m much like that,” Colton continued. “I was also a one-game wonder but it would have been a tragedy if I’d only been able to be a writer for one day. This is much more fulfilling and rewarding for me. It’s who I am.”23

“I’m proud of my writing career. In terms of baseball, I was born that way — with a good arm. If I had worked at my baseball career with the same diligence as my writing career, I might be in the Hall of Fame.”24

“I got hurt doing something I shouldn’t have been doing. But the good thing is that I never would have been a writer if it didn’t happen. Becoming a writer did not cross my mind once in all those years of playing baseball. I feel much better about my writing career than I do about my baseball career. I think of myself as a writer.

“I’ve been a writer now for over 40 years, and there’s never been one day I wake up not loving my job. That makes me a very lucky guy.”25

Acknowlewdgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

Sources

Baseball-reference.com

Baseball-almanac.com

Retrosheet.org

Notes

1 Larry Colton, face-to-face interviews with author, January 4, 2012; January 6, 2019 (hereafter Colton interviews 1 and 2).

2 Philip Howlett, “Letter from the Publisher,” Sports Illustrated, May 24, 1981.

3 Larry Colton, “As I Did It,” Sports Illustrated, Sept. 25, 1977.

4 Stephen Shearer, Beautiful: The Life of Hedy Lamarr, New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2010.

5 “Hedy Takes a Pitcher-in-Law,” Life, July 23, 1965, 32A.

6 Larry Colton, Goat Brothers, New York: Doubleday, 1993, 232.

7 Larry Colton, interview, February 9, 2019.

8 Larry Colton, e-mail, February 17, 2019.

9 Colton interviews 1 and 2.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Larry Colton, “Nostalgia,” Sports Illustrated, May 24, 1981, 120-124.

16 Colton’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame

17 Ibid.

18 Colton interviews 1 and 2.

19 Dave Jarecki, “Where Are They Now? Larry Colton,” BaseballSavvy.com (http://www.baseballsavvy.com/w_larry.html), accessed December 2018.

20 Gail Bowen McCormick, “Larry Colton,” BrainstormNW, April 2005 (http://brainstormnw.com/News/15FascinatingPeople.html)

21 Colton, Goat Brothers, viii.

22 Jeff Baker, “Bookmarks: Wordstock founder Larry Colton receives special Oregon Book Award” The Oregonian, January 15, 2013 (https://www.oregonlive.com/books/index.ssf/2013/01/bookmarks_wordstock_founder_la.html )

23 Annette Utz, “Oregon Author at a Fever Pitch,” Statesman Journal (Salem, Oregon), March 11, 2015.

24 Colton interviews 1 and 2.

25 Ibid.

Full Name

Lawrence Robert Colton

Born

June 8, 1942 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.