Mose YellowHorse

Though Mose YellowHorse toed the rubber for two underachieving Pittsburgh Pirates teams in 1921 and 1922, he left an indelible mark on the club and its fanbase. Because of his off-the-field antics and on-the-field accomplishments, YellowHorse was a longtime fan favorite. Those in executive and administrative positions with the Pirates were not so quick to share the fans’ enthusiasm for the Pawnee Nation citizen. Ever the competitor, YellowHorse fully embraced the role of athlete-entertainer and enjoyed putting on a good show for paying customers.

Though Mose YellowHorse toed the rubber for two underachieving Pittsburgh Pirates teams in 1921 and 1922, he left an indelible mark on the club and its fanbase. Because of his off-the-field antics and on-the-field accomplishments, YellowHorse was a longtime fan favorite. Those in executive and administrative positions with the Pirates were not so quick to share the fans’ enthusiasm for the Pawnee Nation citizen. Ever the competitor, YellowHorse fully embraced the role of athlete-entertainer and enjoyed putting on a good show for paying customers.

Born on January 28, 1898, to Thomas YellowHorse and Clara (Ricketts) YellowHorse in Pawnee, Oklahoma, Mose grew up on or near the Pawnee Nation during most of his childhood.1 Those exceptions included going “on the road” with his father to perform for Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show and attending Chilocco Indian School, from which he frequently fled during his teenage years.2

In the 1870s, after the Pawnee Nation was forced to cede their traditional homelands in Nebraska, YellowHorse’s parents, then children, were among those who walked 400-plus miles to present-day Pawnee, Oklahoma. Once there, chaos and dysfunction were the order of the day. Pawnee Agency officials were slow to comprehend or meet the needs of the displaced population. Supplies and resources promised to the tribe by treaty agreement were often late arriving and usually short on required inventory. Some quartermasters in charge of doling out food rations and other goods were not typically sympathetic to those they thought of as “vanishing.” That is, many non-Natives believed or perpetuated a prevailing myth that Indigenous populations were going to disappear or assimilate completely into the mainstream. Regardless, during the mid- to late nineteenth century, and even into the early twentieth century, numerous instances of theft and/or fraud by Indian agents and others within the system were documented and even prosecuted on rare occasions.3

Despite such challenges, Clara and Thomas eventually met, courted, and had a son who entered a world of future uncertainties: At the end of the nineteenth century, the so-called “Indian Wars” had reached a conclusion, at least according to settler-colonial ways of thinking; the Spanish-American War was fought (April to August 1898), bringing an end to Spanish presence in the Americas; and, in Russia, Vladimir Lenin established the Communist Party, which would have worldwide ramifications.

As a youngster in the Oklahoma Territory, Mose and his parents struggled. In a photo, Mose and his father are shown in Native regalia, a Pawnee father and son with stoic expressions – similar to many others during the same period. Since father and son performed in Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show, it is possible the photo was taken for such an occasion. It is also possible Thomas farmed on his allotment (#76) land in Pawnee County; as for Clara, she is documented helping with traditional female Pawnee domestic work.

While Indian agents and other corrupt officials were often skimming off the top, other economically-minded businessmen were developing different ways to exploit both Native labor and non-Native audiences. The evolution of Wild West shows began near the close of the Civil War (or shortly after, depending on one’s source). The shows were a theatrical mix – usually outdoors, usually traveling – of vaudeville, historical reenactments, and staged performances. They provided romanticized depictions of outlaws, Natives, cowboys, wild animals, and military scouts. Three prominent shows included those by Buffalo Bill, Pawnee Bill, based in Pawnee, Oklahoma, and the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch, which was located outside of Ponca City, Oklahoma.

According to oral histories, YellowHorse developed his strong pitching arm by throwing rocks while hunting for small game. Several elders recounted how he often filled his rucksack with squirrels, rabbits, and other animals with strong throwing and good aim. Early on, he also developed a lifelong love of fishing.4

As part of the country’s assimilationist policies, YellowHorse attended the Pawnee Industrial School for several years before going to Chilocco Indian School, where he studied carpentry. Eventually, he went out for the baseball team and played for several seasons, often sitting on the bench and participating in practices, before starring on the team in 1917. That year, he pitched to a 17-0 record, beating such competition as the University of Tulsa (then Henry Kendall College), Oklahoma State (then Oklahoma A&M), and other small schools, including Friends University and Bethany College. YellowHorse’s success at Chilocco did not occur overnight, nor easily.5

Numerous records at the Oklahoma Historical Society indicate that YellowHorse often left Chilocco – interpret: ran away – to return to Pawnee, a distance of about 60 miles.6 It’s not difficult to imagine YellowHorse the young outdoorsman making his way from the northernmost and central part of the state to Pawnee County, crossing the Arkansas River along the way. He certainly wouldn’t have had much fear making such a journey on foot. Not surprisingly, such impulses were common for Native youngsters who were taken from their communities and missed their parents as well as the comforts of home. His mother, Clara, had died in 1916, aged 52 – a year before Mose last attended Chilocco. She is buried in the North Indian Cemetery, which is adjacent to Highland Cemetery outside of Pawnee.

After YellowHorse’s stellar season with Chilocco, he garnered the attention of area coaches and scouts and signed with the Des Moines Boosters of the Western League, which he did for a short time in 1918 – before the league folded operations because of World War I. YellowHorse then returned to Pawnee and kicked around with a few sandlot and semipro teams, getting work when and where he could.

Then, in the spring of 1920, YellowHorse received an unexpected invitation by mail, which also included ample train fare from Pawnee to Little Rock, Arkansas.7 The note from Norman “Kid” Elberfeld requested YellowHorse’s presence for a tryout. Elberfeld also noted YellowHorse’s former teammate at Chilocco, Bill Wano, highly recommended the Pawnee flinger for the opportunity. Though the tryout went well and YellowHorse made the team, the beginning of the season was unbalanced for the new starter. After tossing to a 7-7 mark and getting sick, he traveled home to Pawnee. Once he returned to Little Rock, YellowHorse dominated the Southern Association, winning 14 consecutive games and concluding the season with a 21-7 record (.750, the best in the league).

The Travelers then faced the Fort Worth Panthers from the Texas League in the inaugural Dixie Series. Much ado was made of the competition, especially in both cities. For his part, YellowHorse was actively engaged in helping the Travelers win two games, though they dropped the series four games to two. In the third game of the series, YellowHorse threw nine innings of five-hit ball, allowing two runs and striking out seven. He also lined a single to right, had one putout, two assists, and retired 12 in a row at one point. His performance prompted Fort Worth sportswriter Pop Boone to proclaim, “Too much Yellowhorse! That tells the story of Fort Worth’s defeat today at the hands of Little Rock in the third game of the Dixie Series.”8

Even as the Dixie Series was unfolding, YellowHorse signed with the Pirates. Announcements of the transaction occurred from Pittsburgh to Pawnee and points well beyond. There was even talk, at least in newspaper circles, of YellowHorse joining the team to close the season, but the minor-league postseason series intervened, and he would have to wait his turn until the spring of 1921.9

The Pirates brought in 48 players for 1921 spring training, an unusually high number for a team picked to contend. Early on in camp, manager George Gibson, a former big-league catcher, took a shine to YellowHorse and spent a lot of time working with him. A 14-year veteran who caught over 1,200 games, Gibson had much to teach the young pitcher.10 The team’s plan was to bring him along slowly, mostly out of the bullpen, and eventually ease him into a starter’s role.

On April 15, 1921, YellowHorse made his major-league debut, against Cincinnati at Redland Field, which the Pirates won 3-1. In two innings of work, YellowHorse struck out one, walked none, and gave up no hits. Retrospectively, he earned a save.11 An unattributed scribe writing for the Pittsburgh Press noted, “Yellowhorse finished for Pittsburg [sic] and although war whoops reverberated through the stands and all sorts of tricks were resorted to in an endeavor to rattle the Pawnee, Mose came thundering through – winner.”12

Thus, YellowHorse was greeted with an unfortunate yet unsurprising dose of racism during his first major-league outing. Pittsburgh Gazette Times writer Charles “Chilly” Doyle stated, much more ambiguously, “Yellowhorse proved a big magnet to the fans who were all abuzz when the Indian walked to the hill. Mose had a fine fast ball and he was handled cleverly by Schmidt.”13 Though Cincinnati had a strong Klan presence at the time, it is likely that such excited behavior by fans had more to do with the lack of Native representation at the highest level of professional baseball.14 It’s quite likely the last Indigenous ballplayer the fans in Cincinnati would have seen was John Meyers, the sharp-hitting catcher for the New York Giants from 1909 to 1915, who retired after the 1917 season.

Thus, YellowHorse was greeted with an unfortunate yet unsurprising dose of racism during his first major-league outing. Pittsburgh Gazette Times writer Charles “Chilly” Doyle stated, much more ambiguously, “Yellowhorse proved a big magnet to the fans who were all abuzz when the Indian walked to the hill. Mose had a fine fast ball and he was handled cleverly by Schmidt.”13 Though Cincinnati had a strong Klan presence at the time, it is likely that such excited behavior by fans had more to do with the lack of Native representation at the highest level of professional baseball.14 It’s quite likely the last Indigenous ballplayer the fans in Cincinnati would have seen was John Meyers, the sharp-hitting catcher for the New York Giants from 1909 to 1915, who retired after the 1917 season.

On April 21 YellowHorse returned to the mound, once again facing the Reds – this time in Pittsburgh and once again in relief. Over 3 2/3 innings, he gave up one run, four hits, and one walk. When the Pirates rallied to win, he also earned his first major-league victory, the first rookie in Pirates history to win a home opener. Then, on Memorial Day, as the Forbes Field faithful filled the stands, with an attendance of nearly 30,000, YellowHorse entered a game against the Cubs in the second inning, the home team down 3-0. One sportswriter described it this way:

“The cries for Yellowhorse were drowning [out] every other noise as Gibby began to warm up relief pitchers. Ponder walked out to start the second inning, but Elmer [Ponder] experienced trouble after he had retired the first batter. The next two Cubs singled and once more the noisy enthusiasts shouted for the Redskin. The protracted yelling broke into a spasmodic riot of approval when the vast audience recognized the athletic boy of the dark visage as he walked coolly from the bullpen toward the mound. Gibby had heard the appeal of the fans and the Chief was going to the firing line.”

He continued with the same energy:

“And what an exhibition the Indian gave from that early period of play through to the finish. Taking the ball with first and second occupied and only one out, the youthful brave seemed to forget the presence of almost 30,000 men, women, and children to go about the task at hand.”

Finally:

“From then on through the warm innings the Indian held the Cubs’ attack runless. Moses went to the pitching post with the Pirates trailing by three runs, but the fourth saw the game deadlocked and the sixth saw [the Pirates] out in front. And all the time the dark-skinned aborigine was handing Walt Schmidt the ball in such a manner as to mystify the hitters of the Chicago club. Truly it was a great day in Moses’ life.”15

Thus was born the long-standing cry of the Pittsburgh faithful to “Put in YellowHorse!” when they wanted a struggling Pirates pitcher to be relieved. The derisive chant stood the test of time, long outlasting YellowHorse. As late as the 1980s, sportswriters continued to reference the YellowHorse cheer.16 With this, YellowHorse became a cultural phenomenon, a spectacle, a wonder, and not just in Pittsburgh.

A week before his Memorial Day game, while the team was in New York taking on the Giants, Pittsburgh Gazette Times writer Doyle noted: “The Giant officials do not give out the exact attendance figures, but Secretary Joe O’Brien informed me that today was the biggest in the history of the field [the Polo Grounds].” He continued, “Mose Yellowhorse was the center of picturesque interest with the early arrivals. The Indian was noted as soon as he walked on the field and the fans were shouting his name with enthusiasm.”17

After the Memorial Day showing, YellowHorse wrote a letter to Pirates fans as a hand-written gesture of gratitude. It was published in the Gazette Times:

Dear Fans,

I was certainly glad to be able to please you after the fine reception you gave me on Memorial Day and trust that I should win many games for Gibby and the Pirates.

It makes one work better to realize the fans are pulling for him.

Yours to the finish,

Chief Moses YellowHorse (signed)

Pawnee Tribe18

The article that accompanied YellowHorse’s letter began with the phrase: “Put Yellowhorse in!!!” (exclamations included), in tribute to the team’s fans.

For the next month, YellowHorse appeared in seven more games, winning three and losing three. He was out of commission because of an injury about two months, until mid-September, pitching his last game against the Giants at Forbes Field. The Pirates team treasurer, S.W. Dreyfuss, provided the following update to C.E. Vandervort, who was YellowHorse’s “guardian,” in a letter dated July 12, 1921: “You have probably seen in the papers that Moses Yellow Horse underwent an operation a few days ago. … During a recent game he strained a ligament and our doctor felt that unless there was an operation to relieve the trouble Yellow Horse would be useless to our club for the balance of the season.”19 Such was not the case, however, as YellowHorse pitched one more inning to close out his rookie season. He finished with five wins, three losses and an ERA of 2.98.

During the season YellowHorse twice met the new commissioner of baseball, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis. The first time was on May 2 in Chicago. According to one account, Pirates manager Gibson took YellowHorse to Landis’s office in Chicago for what was described as “an interesting meeting,” during which Landis “seemed pleased with the appearance of the aborigine and soon was engrossed in asking chief some personal questions.”20 The second time was in Pittsburgh on June 20, when Landis attended a Pirates game against Philadelphia. YellowHorse pitched eight innings of seven-hit ball, giving up two runs and striking out seven, helping lead Pittsburgh to a 3-2 victory and outdueling veteran Lee Meadows.21 By all accounts, Landis was impressed by YellowHorse’s personal demeanor and his pitching performance.

As the 1921 season unfolded, the Pirates remained more than competitive, consistently holding a modest lead in the National League over the Giants. At one point, the Pirates were 36 games over .500. However, a five-game sweep to the Giants in late August reversed the Pirates’ fortunes. They eventually finished in second place.

Once the season was over, YellowHorse, along with other major-league players, played in what was then dubbed the “World Series of Oklahoma” in Oilton, one of many barnstorming tours across the country. The game was to be played on October 30, featuring YellowHorse for the visiting Pawnee-Cleveland team and Walter Johnson for the home team, Oilton. It was rained out. Instead, on November 9 YellowHorse defeated White Sox veteran Dickey Kerr, 8-2.22

During the offseason, YellowHorse returned to Pawnee, rested, and recuperated, healing from his surgery as well as in-season tonsillitis. His teammates voted him a full share of the team’s second-place money. (It was standard practice at the time for the second-place teams in each league to receive payment from the Series.23) The prevailing sentiment among sportswriters anticipated a more positive outcome for 1922.

As 1922 spring training commenced in West Baden, Indiana, manager Gibson hoped to build off YellowHorse’s shortened rookie season. Shortly after reporting to camp, YellowHorse was teamed with the other frontline pitchers. Charles Doyle wrote, “Gibby showed his high regard for Moses Yellow Horse’s ability at the outset. … Chief drew a first-squad uniform … and was told to limber up with the aces of the mound.” Doyle added that Gibson thought “the Indian has one of the fastest balls in baseball and he has no hesitancy in saying so.”24 Once the late-arriving YellowHorse reported to camp, he “took occasion to deny a rumor … to the effect that he had taken unto himself a squaw.”25

Once the season commenced, the Pirates performed well enough, getting off to a 27-19 start by June 10. At that point YellowHorse’s ERA stood at an unremarkable 5.01. From June 11 through June 30, the Pirates greatly underperformed as well, going 6-14, and once again getting beat up by the Giants along the way. On June 30 Gibson resigned and team owner Barney Dreyfuss appointed coach Bill McKechnie to succeed him. After McKechnie took over, the team went 53-36-1, good enough to tie for third place in the league. For his part, YellowHorse’s line was fairly uneven: He pitched in 28 games and was 3-1 with a 4.52 ERA. More telling, in 77 2/3 innings pitched, YellowHorse gave up 92 hits, with a WHIP of 1.442.

YellowHorse’s off-the field shenanigans with future Hall of Famer Rabbit Maranville dominated too much of his season. One instance promulgated by sportswriter Frederick Lieb but contradicted by the Pittsburgh press, allegedly occurred when the Pirates were on the road facing the Giants. Lieb wrote that new manager McKechnie “held a [team] meeting before the first game with the Giants and laid down his disciplinary law. He was emphatic about bootleg liquor, the hour the men should be in bed, [which was midnight] and that sort of thing.”26

Lieb wrote that Maranville and YellowHorse, bored in the early afternoon in New York, decided to squelch their restlessness with some high-rise antics:

“When the team checked in, McKechnie shared his suite with [Maranville and YellowHorse, who were roommates].

“McKechnie started to undress. He opened a closet door and almost toppled over as a flock of trapped pigeons flew into his face. Bill recovered and, madder than a hornet, he shouted so loud that he awakened Maranville. ‘What goes on here, Rabbit?’

“Rabbit blinked and replied: ‘Hey Bill, don’t open that other closet. Those pigeons that got out belong to the Chief – mine are in that one over there.’

“With popcorn and other tempting goodies, the two Pirate zanies had coaxed many pigeon residents of the district from a perch high up on the hotel into Manager Bill’s apartment.”27

Near the end of the season, on September 26, the Pirates traveled to Detroit for an exhibition game against the Tigers, a contest YellowHorse started and lost. During the game, the Pirates pitcher plunked Ty Cobb so hard he had to be carried off the field.28 Decades later, Pawnee Nation citizen, Norman Rice, alleged YellowHorse beaned Cobb because the latter decided to dance mockingly around home before a plate appearance.29

On another occasion, about a month later, well after the season and World Series were completed, YellowHorse and Babe Ruth played in a barnstorming game in Drumright, Oklahoma. According to one account, which was published in The Pawnee Chief 70-plus years after the fact, YellowHorse supposedly struck out Ruth twice, once with the bases loaded.30 However, newspaper accounts of the day do not mention any such heroics by YellowHorse. Once again, it seems YellowHorse’s legend stretches beyond verification.

By December of the same year, the Pirates traded YellowHorse to the Sacramento Senators of the Pacific Coast League. The Pawnee hurler relished the situation and stated as much. He imagined the change in teams, situations, and scenery might allow for more pitching opportunities. According to the Los Angeles Evening Post-Record, YellowHorse’s new manager, Charlie Pick, a former big-leaguer himself, “promised the Oklahoma tribesman all the work he can handle.” Pick was quoted: “The way he is showing up in spring practice indicates he is going to be up among the pitching aces in the circuit.”31

During the 1923 season, YellowHorse pitched in 53 games, earned 22 wins against 13 losses, and threw 311 innings – this for a Senators team that finished second in the league, 11 games behind the San Francisco Seals. Such a workload represented his most sustained campaign since pitching for Little Rock, when he logged 278 innings of work in 46 games.

After being among the PCL leaders in pitching wins the previous season, optimism regarding YellowHorse’s potential in 1924 permeated the sport pages in Sacramento. Such hopefulness was quickly squashed when, in mid-May, he “hurt his arm during practice,” while he “was in the outfield and he cut loose with a vicious peg to the plate,” and “something snapped in his right arm and the big Indian was through for the day.” The article goes on to state, “Later in the afternoon Colonel [Charlie] Pick tried to use Moses as a relief twirler, but after warming up the Chief threw his glove away in disgust. His arm bothered him so much that it was impossible for him to bear down.”32

A different account by Bob Lemke, writing in The Bleacher Bum (in 1994), suggests YellowHorse permanently injured his arm during a game in Salt Lake City. According to Lemke, Sacramento was playing in Salt Lake City and doing so with a comfortable 18-5 heading into the bottom of the ninth. The Bees then rallied to score 10 runs, during which manager Pick told YellowHorse to warm up quickly. The article continues:

“With only three warm-up pitches, Yellowhorse [sic] was called to the mound with the bases loaded, the tying run on first base. He reminisced later, ‘I went in and I threw just nine pitches, striking out in order John Peters, Tony Lazzeri and Duffy Lewis,’ and nailing down the victory.”

“‘That was the finest job of pitching I ever did,’ Yellowhorse [sic] said, ‘But I couldn’t raise my arm the next day. Jack Downey was the trainer but he couldn’t stop the pain.’”33

Unfortunately, there are no citations in Lemke’s article, so source verification is difficult and attempts to find either stories or quotations related to the incident via newspapers.com and other resources were not specific. One account in the Salt Lake City Deseret News provides the following snippet: “Mose Yellow Horse finished up and with his fast ball [sic] he turned back the ambitious Bees.”34 Suffice it to say, if YellowHorse pitched an immaculate inning, which included striking out a future Hall-of-Famer in Lazzeri, and two former major leaguers, it certainly would have been some of his best work as a professional.

Regardless of which account is true, YellowHorse’s physical demise from the game was instigated. He pitched in a few more games for the Solons but ended the season with one win and four losses and an ERA of 6.07. By mid-June, Sacramento released him to Fort Worth of the Texas League, where he did not pitch and was then returned to Sacramento. YellowHorse then went AWOL and was suspended by his former team.

YellowHorse’s 1925 and ’26 seasons were equally disappointing. He pitched sparingly for teams in Mobile, Alabama (in the Southern Association, again, and reunited with Kid Elberfeld), Sacramento, and Omaha in the Western League. He pitched in a game for Omaha on May 1, giving up five runs off six hits in 2 1/3 innings. Seven weeks later, YellowHorse was back in Oklahoma playing semipro ball for the Fairfax Indians and Ponca City Oilers among others, his professional playing days finished.”35

YellowHorse returned to Pawnee, played lots of semipro ball with an assortment of teams, and spent the next decade in survival mode. He continued to drink – probably too much for his own good – and held odd jobs, living with relatives and others, getting by as he could. One notable event from this period included the creation and appearance of a cartoon character, “Chief Yellowpony,” in the Dick Tracy comic on March 27, 1935.36 Since both hailed from Pawnee, with Tracy creator Chester Gould, two years YellowHorse’s junior, it was no surprise that such a character would show up. Gould often used settings and developed characters he knew from his hometown.

Otherwise, YellowHorse regularly played semipro and pickup baseball, even in city leagues, as often as he could, or cared to do so, through the mid-1930s. Local reports indicate he quit pitching for the most part and became an outfielder. In 1927, he even won the Muskogee City league batting title, hitting at a .412 clip.37 By 1931, YellowHorse was also coaching baseball, managing Pawnee Bill’s Indians in a number of area tournaments. Numerous stories from area newspapers clearly specify he stayed active as a player/manager though 1935.

As noted in 60 Feet Six Inches from Home: the (Baseball) Life of Mose YellowHorse, several other noteworthy activities and events which took place include: serving as an umpire the Kansas-Missouri-Oklahoma League; working as a groundskeeper for the Ponca City Drillers minor league club; presenting Pawnee war bonnets to the competing World Series managers during the 1954 fall classic between the Cleveland Indians and New York Giants;38 having one of his gloves put on permanent display at National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; receiving tributes in Little Rock; and, attending “Chief YellowHorse Night” in Sacramento.

YellowHorse later worked a steady job with the Oklahoma State Highway department in the construction department. In January of 1964, the Pawnee Nation held a dinner in his honor. Three months later, on April 10, he passed away at the age of 66 of heart failure and complications from diabetes. With his passing, a unique and humorous hard-throwing sharp-shooter crossed over. Many tributes appeared across the country, including in Pittsburgh, where former teammate Charlie Grimm remembered YellowHorse “had a good fast ball. A very good fast ball,” and went on, saying former Pirates catcher Walter Schmidt “thought Yellowhorse [sic] threw harder than any pitcher he ever caught.”39 More than 40 years after he played for the Pirates, Steel City fans continued to chant “Put in YellowHorse!” as the Pittsburgh Gazette Times noted in its obituary.40

Other posthumous honors occurred, as well: induction in 1971 into the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame (strangely enough, this organization existed in theory only, and a location was never secured); in 1994, he was inducted into the American Indian Athletic Hall of Fame; and, having a street in Pawnee named in his honor, Mose YellowHorse Drive.

To be sure, Mose YellowHorse was one of the most revered short-timers to play the game. In Little Rock, Pittsburgh, and Sacramento, he went in blazing, made his mark, and left long-lasting and (mostly) positive impressions with fans, writers, and teammates (management was a different story). His wit was classic, his timing impeccable. Take this one: of his frustration regarding his relief role with the Pirates, YellowHorse quipped “just call me Chief Sitting Bull Pen.” Also, a story published in The Seattle Star shared:

“One night last summer in Oakland Moses Yellowhorse, the Pawnee Indian pitcher with the Sacramento team woke up Charley Doyle, the club secretary and told him that a taxi driver was holding him up for a $37 dollar fare for a short ride.”

“Doyle dressed and went down to see about it.”

“‘How about charging this man with a $37 dollar fare?’ asked Doyle, in none too good a humor for having been awakened.”

“‘Sure boss,’ said the driver, “Thirty-five dollars for liquor and $2 for taxi.”41

“Charley” Doyle was, of course, Charles Doyle, one of the beat writers for the Pittsburgh Gazette Times, who also wrote a column, “Chilly Sauce,” in which he wrote about YellowHorse a number of times.

Though YellowHorse had a sustained period of sobriety the last fifteen-plus years of his life, he apparently started drinking again, right at the end of his life, according to anthropologist Martha Blaine. She attended and recorded Mose’s birthday honor dance and later went to his funeral. Mose, ever the showman, had a legendary fastball and a quicker sense of humor with a unique ability to fascinate and entertain while tossing pitches. His was a life quenched and full – a one-of-a-kind self-promoter who rarely lacked confidence in his skills and never hesitated with a story, as is the Pawnee way.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com.

For a more complete biography of Mose YellowHorse, see the Todd Fuller’s mixed-genre work, 60 Feet Six Inches and Other Distances from Home: The (Baseball) Life of Mose YellowHorse (Duluth, Minnesota: Holy Cow! Press, 2002).

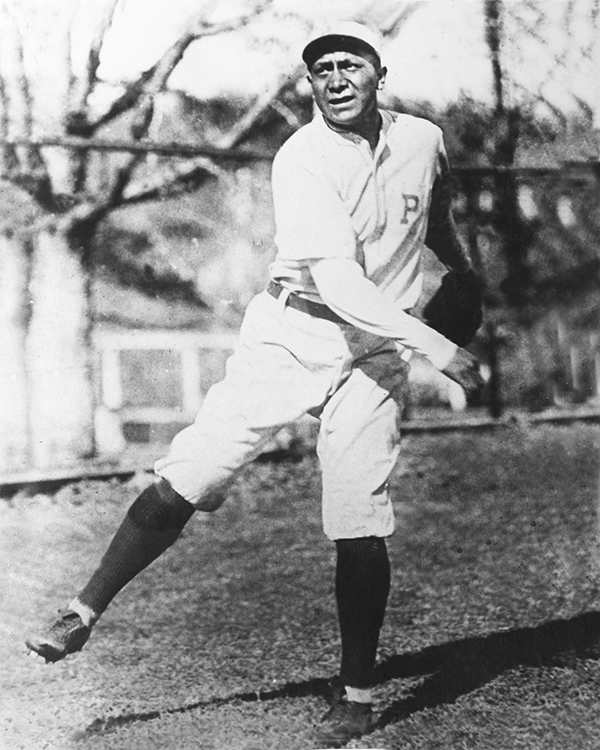

Photo credits: Mose YellowHorse, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 From YellowHorse’s “Delayed Certificate of Birth,” which was issued December 27, 1951, by the State of Oklahoma – Department of Health. Some sites incorrectly state his birth as March 28, 1898.

2 A faint photo of little Mose (three or four) and his dad in exists, which the author saw in a Pawnee Homecoming annual after 60 Feet Six Inches and Other Distances from Home: the (Baseball) Life of Mose YellowHorse, is from the Oklahoma History Center holdings.

3 See William Unrau’s article “The Civilian as Indian Agent: Villain or Victim?” in the Western Historical Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 4 (October 1972), 405-420.

4 Todd Fuller, 60 Feet Six Inches and Other Distances from Home: the (Baseball) Life of Mose YellowHorse (Duluth, Minnesota: Holy Cow! Press, 2002), 72.

5 An article from The Indian School Journal, “Base Ball,” notes the team’s success against schools such as Friends University (Wichita, Kansas) on p. 521.

6 In December of 1999, as a graduate student (PhD in English), the author visited the Oklahoma History Center and read several letters between the Chilocco superintendent and C. E. Vandervort, in which the head of the school informs Mose’s “guardian” he has run away, again.

7 “Yellow Horse Looms Up as Best Prospect in League,” Pawnee (Oklahoma) Courier-Dispatch, June 24, 1920: 7.

8 Pop Boone, “Elberfeld’s Indian Phenom Hits Stride and Travelers Win Third Game from Cats,” Fort Worth Record-Telegram, September 24, 1920: 10.

9 “Pirates Collecting Big Squad of Rookies,” Cincinnati Post, September 21, 1920: 14.

10 https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/g/gibsoge01.shtml.

11 Saves were not a baseball statistic in 1921.

12 “Ponder to Likely Hurl Final Contest at Redland – Bucs Begin Series with Cubs Tomorrow,” Pittsburgh Press, April 16, 1921: 8.

13 Charles Doyle, “Buccaneer Bingles,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, April 16, 1921: 9.

14 See www.newspapers.com/image/34617054/?match=1&terms=Ku%20Klux%20Klothes%20.

15 Charles Doyle, “Pirates Beat Chicago Twice, 13-0 and 6-3,” Gazette Times, May 31, 1921: 3.

16 Joe Browne, “She Could Be Bucs Ace in the Hole,” Gazette Times, June 23, 1983: 18.

17 Charles Doyle, “Chilly Sauce,” Gazette Times, May 23, 1921: 7.

18 Drew Rader, “Chief Yellowhorse and His ‘Roomie,’” Gazette Times, June 5, 1921: 23.

19 Moses YellowHorse player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. It was common practice by the U.S. government during this period to appoint so-called non-Native guardians to “protect” Native people with potential means. In YellowHorse’s case, a prominent banker in Pawnee, C.E. Vandervort, was this individual.

20 Charles Doyle, “Yellowhorse Holds Confab with Landis,” Gazette Times, May 3, 1921: 11.

21 See https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/PIT/PIT192106200.shtml.

22 “Oilton Lost in Ball Game Last Sunday,” Oilton (Oklahoma) Gusher, November 10, 1921: 6.

23 Moses YellowHorse player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

24 Charles Doyle, “Bucs Gingery in First Outdoor Session,” Gazette Times, March 4, 1922: 9.

25 Charles Doyle, “Adams and Whitehill Absentees from Pirates Training Camp,” Gazette Times, March 3, 1922: 32.

26 Frederick G. Lieb, The Pittsburgh Pirates (New York: Putnam’s Sons, 1948), 195.

27 Lieb, The Pittsburgh Pirates, 196. Lieb’s account conflicts with newspaper stories of the day, which were published in two Pittsburgh papers and clearly state YellowHorse was in Pittsburgh during the first series in New York, which took place from July 29 – August 1, a four-game sweep for the Pirates. Both papers also state YellowHorse was in Pittsburgh recovering from tonsillitis.

28 “Cobb Is Shelled by Yellowhorse,” Reading (Pennsylvania) Times, September 27, 1922 10.

29 Fuller, 102-103.

30 Fuller, 110.

31 “From Majors to Sacs – and Glad of It!” Los Angeles Evening Post-Record, March 12, 1923: 17.

32 John H. Peri, “Seals – Sac Battle Will Draw Fans Sunday Morning,” Stockton (California) Daily Evening Record, May 15, 1924: 17.

33 Bob Lemke, “Pirates Pawnee Pitcher went ‘way of all bad injuns,’” Bleacher Bum (Iola, Wisconsin), March 4, 1994: 62.

34 Les Goates, “Locals Drop Doubleheader Saturday and Lose Hectic Series,” Deseret News, May 12, 1924: 8.

35 See https://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.fcgi?id=yellow001mos. The author also has a record that shows YellowHorse won two games for Mobile in 1925, neither of which is included on his reference page.

36 Chester Gould, “DICK TRACY – Indian Call,” Chicago Tribune, March 27, 1935: 18.

37 “City Loop Slug Title Goes to Yellowhorse,” Muskogee Daily Phoenix and Times-Democrat, August 28, 1927: 6.

38 “Pawnee’s Mose YellowHorse Attends World Series Games, Presents War Bonnet to Cleveland and New York Managers,” Pawnee (Oklahoma) Chief, October 7, 1954: 1.

39 Lester J. Biederman, “Grimm, Cub Official, Recalls Playing Days with Yellowhorse,” Pittsburgh Press, April 16, 1964: 50.

40 “Yellowhorse, Former Buc Pitcher, Dies,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 14, 1964: 26.

41 “Today’s Giggle: Some Taxi Fare,” Seattle Star, August 6, 1924: 10.

Full Name

Mose J. YellowHorse

Born

January 28, 1898 at Pawnee, OK (USA)

Died

April 10, 1964 at Pawnee, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.