Ralph Schwamb

Tried and convicted of murder in a court of law, Ralph “Blackie” Schwamb hurled his best pitches from behind prison walls. The tall, lanky right-hander with a nasty temper and a taste for booze won just a single game as a major leaguer. He won 131 games while playing for teams based at the San Quentin and Folsom state penitentiaries in California.

Tried and convicted of murder in a court of law, Ralph “Blackie” Schwamb hurled his best pitches from behind prison walls. The tall, lanky right-hander with a nasty temper and a taste for booze won just a single game as a major leaguer. He won 131 games while playing for teams based at the San Quentin and Folsom state penitentiaries in California.

Schwamb threw a fastball and a curveball that could baffle hitters. He also found his way into frequent trouble and heard the click of handcuffs more than once. Blackie claimed, with some exaggeration, “I always had an angle. Things were too easy for me. It seemed that whatever I decided to undertake, I could make work.”1

Born on August 6, 1926, in Los Angeles, Ralph Richard Schwamb grew up in a neighborhood south of downtown. His mother, Jeannette (née Tarling), was born in 1904 in Montana. Ralph’s father, Chester Hinton Schwamb, was two years older than Jeannette and hailed from Colorado. The couple got married in 1921 and set out for Southern California, along with so many others.

Just over 100,000 people lived in Los Angeles in 1900. That number had grown to nearly 600,000 by 1920 and would top 1.2 million in 1930. Bulldozers ran over acres of orange groves and wildflowers to meet the demand for new housing. Chester Schwamb built a successful career working in the local construction industry as a “carpenter and master builder.”2

Ralph and his older brother, Chester Jr. (born in 1923), attended 68th Street Grade School. One day, while watching a Western movie with friends at a local theater, Ralph noticed that the bad guys wore black. He decided to do the same. Young Ralph liked the look. Friends started calling him Blackie.

He was a gangly kid and a good all-around athlete who competed at the local parks against future big leaguers like Gene Mauch, Al Zarilla, and George Metkovich. Schwamb made himself a sandlot sensation with his intimidating fastball. He could always throw hard. Once, on a dare and from a reported 300 feet away, Schwamb picked up a rock and broke a “big pane” of glass that workers were hauling away from a nearby factory.

Blackie quit Washington High School at the age of 16. He was already a big drinker and a nasty drunk. Mauch recalled that even as a teenager, “When sober, Blackie was one great kid. With alcohol, he actually pursued daring and trouble.”3

Schwamb turned 17 years old on August 6, 1943. He celebrated by joining the Navy. Patriotic fervor, though, even during this time of world war, could never trump Schwamb’s habit of getting into mischief. He spent more time fighting fellow servicemen than he did the Germans or Japanese. Just a few months into his tour, while on leave in Los Angeles with thousands of other soldiers and sailors, Blackie slugged a military officer and was jailed.

After a few more unpleasant incidents, Schwamb left the Navy with a bad-conduct discharge from the Great Lakes Naval Training Center in Chicago and headed back home. Blackie, who had grown to 6-feet-5-inches, asked about joining one of the local baseball leagues. Evo Pusich, a recreation supervisor at the Manchester Playground and a part-time scout for the New York Giants, called Schwamb “an awfully nice kid.”4

On March 8, 1946, Blackie married Nellie Ann Eisen, a Minnesota native. Ralph and Nellie, or Nell, were both 19 years old. The couple’s son, Richard Page Schwamb, was born on December 6, 1946.

At some point, Blackie met a diminutive (5-foot-5) tough guy named Meyer Harris “Mickey” Cohen. Born in 1913 in Brooklyn, New York, to Jewish immigrants from Kiev, Russia, Cohen grew up in the Boyle Heights area of East Los Angeles and quickly built a nasty rap sheet. At the tender age of 7, he picked up a hot plate and assaulted a police officer. Two years later he robbed the Columbia Theater in downtown LA.5 Police nabbed Cohen and a judge ordered him to the local reform school.

Later, Cohen took up boxing but rarely strayed from a life of crime Through the years, in California and elsewhere, he got to know other gangsters, including Al Capone, Meyer Lansky, and Bugsy Siegel. Cohen also made himself into a minor celebrity. Readers often saw his picture in the local newspapers. Cohen owned an armor-plated car and a house in the upscale Brentwood section of West LA.

Schwamb met Cohen in late 1945. The hoodlum put Blackie to work as a so-called leg-breaker. The young right-hander collected debts from gamblers who had run into a streak of bad luck.6 He also hooked on with a local semipro baseball team as a pitcher and occasional shortstop.

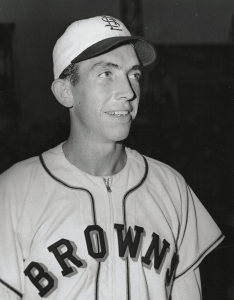

Both the Cleveland Indians and St. Louis Browns kept an eye on Schwamb. St. Louis signed him in September 1946 and gave him a $600 bonus. Jack Fournier, the former first baseman-outfielder for the Brooklyn Robins and other teams and now a Browns scout, liked the slender hurler. Well, Fournier liked Blackie in the way that many other baseball people liked Blackie. That is, with a certain amount of reserve. “He’s a screwball, but he can pitch,” Fournier said.7

Schwamb began his brief tour in professional baseball as a member of the Aberdeen (South Dakota) Pheasants of the Class-C Northern League. He won five games in as many decisions and posted a 1.62 ERA. As usual, he spent many of his off-hours at local bars, and the Browns shipped him to the Globe-Miami Browns, another of the organization’s Class-C affiliates, based in the old silver-mining town of Globe, Arizona. Blackie pitched and drank, this time with the desert as a blurry backdrop.

To the surprise of many, Globe advanced to the Arizona-Texas League championship series and played the Tucson Cowboys. Manager Lloyd Brown called on Schwamb to be his ace. First, though, Brown bailed him out of the local jail following one more of the pitcher’s drunken escapades. It was a decision the skipper did not regret. Blackie won two games in a best-of-five series and recorded a save in the championship matchup. He struck out 23 batters over a combined 19 innings. Still, it wasn’t easy. Browns pitcher Ned Garver heard several stories about Schwamb, including this one: “The only way they kept him sober for the championship series was that every night after the games, they would take him back to jail and lock him up until the morning.”8

Blackie began the 1948 campaign with the Toledo Mud Hens of the Triple-A American Association, the Browns’ top farm team. Bob French from the Toledo Blade noted Schwamb’s great height and wrote, “[A]ccording to reports, he has a wild and carefree idea about how a baseball player should conduct himself. But he has so much speed they say that he can throw an egg through a bullet-proof safe.”9

As is the fate of most pitchers, especially those toiling away in the minor leagues, Schwamb sometimes suffered from a poor defense behind him, and he rarely took those error-filled affairs in stride. Frank Mancuso, the Toledo catcher, said, “After one game, he wanted to fight the entire team. Man, he was hot. I don’t blame him, but you gotta get along with your teammates.”10

Nothing Schwamb did for Toledo indicated that he held star potential. He won one game and lost nine in 25 appearances, with a 5.14 ERA over 77 innings. He also walked 52 batters and struck out just 45. The Browns called him up in late July, anyway.

Blackie made his big-league debut in the second game of a doubleheader against the Washington Senators on Saturday, July 25, at Griffith Stadium. The Senators won the opener, 5-1, behind Ray Scarborough. Fred Sanford took the loss.

Schwamb started against Earl Harrist, a third-year right-hander from Louisiana. St. Louis scored twice in the first inning and added two more runs in top of the third. Washington got to Schwamb for one run in the bottom half of the third.

Washington added two more runs in the seventh inning. Mickey Vernon began the rally with a one-out single. Junior Wooten lined another base hit, and both runners advanced an additional base on center fielder Paul Lehner’s throw into the infield. Jake Early’s two-run single to right field ended Blackie’s afternoon.

Besides giving up three runs – two earned – Schwamb allowed seven hits and struck out three. Washington tied the score in the ninth inning on an unearned run with Bryan Stephens pitching. St. Louis won, 6-4, on a Don Lund two-run double in the 11th. The following day, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported that Blackie “pitched great ball for the first six innings.”11

Schwamb earned his lone major-league victory six days later. Once again, he faced the Senators. This time, he took the mound at Sportsman’s Park. The game drew 4,556 fans on a warm summer day. Schwamb started against Walt Masterson. Washington scored two runs, one unearned, in the opening frame. St. Louis fought back and scored twice in the third, once in the fifth, and seven times in the sixth to blow open the game, 10-2.

Blackie, though, made the game interesting. He allowed four runs in the seventh inning on two walks and four singles. Bryan Stephens, who attended the same high school as Schwamb, entered the game with one out and wiggled out of the jam. The Browns went on to win, 10-8. Schwamb’s pitching line – eight hits, six runs with five of them earned, four walks, and just two strikeouts – wasn’t pretty but it was good enough to put him into the win column, thanks to a lively St. Louis offense.

In the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Robert Morrison wrote, “Brownie bats, which have had an occasional habit of speaking with authority lately, did it again last night” and added that while Washington nearly staged a comeback, “everything turned out all right.”12 Blackie said later, “I had my first major-league win. I was just a week shy of my twenty-second birthday. I had the world by the tail.”13

As happened so often with Blackie, though, the good times ended fast. He struggled from the get-go in his next game, on August 4 at home, and lasted just one-third of an inning, in which he “was kayoed”14 by the Boston Red Sox. He allowed five hits and six runs, all of them earned. The Browns, though, scored seven times in the bottom of the first and won, 9-8.

Four days later, Schwamb started at home and lost to the Philadelphia Athletics, 7-5. He gave up two runs and got the hook with two out in the fourth inning. The Browns ordered him to the bullpen. In his first two relief appearances, Schwamb gave up a combined nine runs (eight earned) in 3⅓ innings but then managed two scoreless efforts.

Blackie’s final month in the big leagues began with another poor outing. He surrendered three runs in three innings against the Tigers on September 6 and, in his last career start, on September 12, he pitched just two innings and allowed three runs against the Cleveland Indians. Two days later, the Philadelphia Athletics roughed up Schwamb for two runs in two innings.

Oddly enough, Blackie’s farewell game, at home vs. the Red Sox on September 18, may have been his best. Manager Zack Taylor sent him in as a reliever with two outs in the sixth inning and Boston already ahead, 11-4. Blackie “checked the Red Sox the rest of the way.”15 He pitched 3⅓ innings of shutout ball, allowing three hits and a walk, with one strikeout. The Browns lost, 11-6. “Schwamb did nice work,” the Globe-Democrat noted.16 About two weeks remained in the season. Blackie watched the rest of the action from a seat on the dugout bench.

The rookie made few friends among his fellow Browns. He often snarled and tossed around insults. He dished out unkind words better than he took them. Fellow pitcher Fred Sanford recalled how Schwamb “acted like a big tough guy, but when players started to get on him, razz him, he couldn’t take it. … We’d call him things like ‘Ears’ or ‘Dumbo.’ He had big ears.”17 St. Louis first baseman Chuck Stevens assessed Schwamb in blunt fashion: “He seemed to go out of his way to break the rules. … Frankly, he was a cancer on that team.”18

St. Louis put together a 59-94 won-lost record and finished in sixth place. Veteran catcher Les Moss led the team with 14 home runs. Sanford topped the Browns with 12 wins; he lost 21times. Schwamb went 1-1 and had an ERA of 8.53 in 31⅓ innings. He gave up 44 hits and 21 walks and struck out just seven.

After the season Blackie boarded a train for Los Angeles. He needed some offseason money and went to see Cohen, who was by now a key player in the LA underworld. In fact, as Bugsy Siegel turned his attention to the future gambling mecca of Las Vegas, “Mickey had taken over his old boss’s Los Angeles operations – as well as Siegel’s organized crime connections back East.”19

Schwamb did unsavory work for Cohen throughout the fall of 1948. He also prepared for the coming baseball season. The Browns held spring training in the Los Angeles suburb of Burbank. St. Louis, still not bullish on the erratic pitcher’s future, offered Blackie a $5,000 contract, the big-league minimum. An angry Schwamb signed on the dotted line.

Jack Graham, a first baseman and second-generation big leaguer, drove Schwamb to practice every day. Not that Schwamb made things easy. Sometimes, Graham had to go looking for his wayward teammate, who was often lying down outside a local bar, sleeping off a bender from the previous night. “That’s the way it went all spring,” Graham said. “Just about every day, he looked like he hadn’t slept, and he smelled like a brewery. Not a pretty sight.”20

Even so, Browns executive Bill DeWitt gave Blackie the good news. Schwamb had made the big-league club. Sorta. DeWitt wanted his hard-living hurler to pitch a few minor-league games before joining the Browns. Schwamb stormed out of the room and soon cut a deal with the Little Rock Travelers, a Detroit Tigers affiliate in the Southern League, where he won two games and had a 2.37 ERA in three appearances. Schwamb, though, missed the team bus to Chattanooga and caught a ride to New Orleans for liquor and the nightlife. He soon found himself an ex-Traveler.

Next, Schwamb went to Sherbrooke, Quebec, about 100 miles east of Montreal, where he pitched in 12 games for the Athletics in the Provincial League. He went 4-4 with an unpleasant 5.73 ERA. Blackie’s baseball future looked bleak, and he needed money, so he pulled a string of offseason robberies in Los Angeles and “took on all the jobs he could get from Mickey Cohen.”21

(Just a few months earlier, on July 20, 1949, outside a popular nightclub on Sunset Boulevard called Sherry’s, Cohen and his cronies traded gunfire with another set of bad guys in what local newspapers dubbed The Battle of Sunset Strip. “Members of Mickey’s party started to drop,” according to John Buntin’s authoritative book on Cohen and the Los Angeles Police Department, L.A. Noir.22 Neddie Herbert, “one of Cohen’s top thugs,”23 took a fatal bullet.)

On the night of October 12, 1949, Schwamb left home for a corner bar named Jimmy’s, where he was a regular. Two friends, Ted and Joyce Gardner, had stopped for drinks at the nearby Colony Club. Dr. Donald Buge, a dentist from Long Beach, also went to the Colony Club that night. His wife, Violet, spent the evening playing poker across the street at the Normandie Card Club.

For unknown reasons, and willingly or not, Dr. Buge left the Colony Club in a car with the Gardners, while Violet Buge stayed at the Normandie. Ted Gardner drove a few minutes away to Jimmy’s. There, the trio met up with Blackie and ordered drinks. Following a round of libations, all four left together in Gardner’s car.

The stories diverge from that point. The bottom line is that Buge was beaten to death, and $53 was stolen from his wallet. Police detectives arrested Ted and Joyce on October 14. Ted confessed and implicated Schwamb, who also was arrested. The district attorney charged Blackie and Ted with first-degree murder.

Blackie told the court that he was “too intoxicated”24 to remember any of the grisly details. Gardner said that he and Blackie had planned to rob Buge. The jury convicted Schwamb of first-degree murder and first-degree robbery. Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Charles W. Fricke sentenced him on December 23 to life in prison. He could apply for parole in 10 years. Gardner, three years older than Schwamb and with a criminal past of his own, also got a life sentence. Neither man said whether Mickey Cohen had ordered the robbery or murder.

Nellie Schwamb left the courtroom, along with her husband’s lawyer, David Silverton. Outside, a friend greeted her with a cheerful “Merry Christmas” but quickly realized the blunder. “Gosh, is that the thing to say at a time like this?” Nell smiled. “Well,” she decided, “in spite of a thing like this, we have to go on living, you know.” 25

Schwamb began his prison term at San Quentin. Opened in July 1852, The Arena – as some called it – lies in a picturesque spot in Marin County, just a few miles north of San Francisco. Cold water from the famous Bay spills onto the nearby shore. Clinton Duffy, the prison’s warden from 1940 to 1952, wrote in his memoir that San Quentin occupies “one of the prettiest pieces of real estate.”26 The prison also has held some of the country’s most notorious criminals, including Sam Shockley, who killed a prison guard during the 1946 Battle of Alcatraz, and the serial killer Gordon Stewart Northcott.

Duffy took the job of warden with reform in mind. He recalled, “San Quentin itself in the old days was often a hell-on-earth, and even today, despite what all of us have tried to do, it is no summer resort.”27 Duffy requested more books for the prison library, added more vocational education courses, and, in maybe his most popular move, ordered the kitchen staff to serve bigger cuts of meat.

Blackie, not long removed from his days as a major leaguer, still wanted to pitch, and San Quentin fielded a team that competed in the San Francisco Recreation Department League. After a series of psychological exams – “He seems very reluctant toward understanding himself and his problems,”28 according to one report – Schwamb suited up, grabbed a glove, and played his first prison-house baseball game for the San Quentin All-Stars on March 11, 1950.

He struck out three batters against Modesto Junior College, and repeated that performance in his next game, versus Marin Junior College. Blackie fanned eight of 10 batters he faced against Reliable Drugs of San Francisco and struck out 14 Galileo Salami batters.

Schwamb was Prisoner Number A-13670. Inmates called him Slick. The team played each weekend on the lower yard at San Quentin. In time, crowds gathered to watch Slick pitch. “After we got the team going and winning,” Schwamb recalled, “you could fire a machine gun in the upper yard on Sunday and not hit anybody.”29

The one-time big leaguer boasted a 2.04 ERA as a San Quentin rookie and struck out 281 batters in 203 innings. When Blackie wasn’t pitching, he played in the field, often at third base, where he could take advantage of that strong arm. He topped the team with a .457 batting average. Plus, he enjoyed his own jailhouse hootch, using yeast, sugar, and a handful of oranges. “It was like cheap wine,” he said.30

Schwamb got a job in the prison’s athletic office. He ordered equipment and uniforms for San Quentin’s various sports teams. At least one guard recalled Schwamb as a “polite”31 inmate, who liked to read everything from the Western writer Louis L’Amour to philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

Baseball practice began in February, and the season lasted until November. Rosters turned over fast, sometimes due to injury, sometimes because a player made parole. Schwamb remained the team’s star. He pitched 32 straight scoreless innings during one stretch in 1951 and kept a .371 batting average. In 1952, the same year that Nell filed for divorce, Blackie threw 162 innings, struck out 261 batters, and fashioned a 1.55 ERA. Plus, he hit at a .377 clip.

In time, Schwamb asked for a transfer to Folsom, another tough prison in the California system, located more than 100 miles from San Quentin and less than 25 miles from the state capital of Sacramento. Prison gangs and gamblers at San Quentin had wanted him to throw games.32

While at Folsom, Blackie competed in the Tri-County League, and, as he did at San Quentin, worked in the athletic office. At one point, he wrote a letter to San Francisco Giants manager Bill Rigney and offered a splendid scouting report on himself. Clearly, Schwamb hoped to get out of prison soon and return to the big leagues. Rigney recalled, “(He was) telling me what a great prospect he is, how he’s striking out everybody there in prison.” The skipper still shook off any idea of signing Blackie. “Are you kidding? He murdered a guy,” Rigney said to team owner Horace Stoneham. “Don’t we have enough troubles on the team without signing a murderer?”33

The prison gates finally opened for Schwamb in January 1960. The state board had granted him parole. He was 33 years old. According to an article in the San Francisco Examiner, “Prison officials said it was their understanding [Schwamb] already had written Baseball Commissioner Ford C. Frick for reinstatement.”34

Schwamb had completed his career as maybe the greatest prison-house pitcher of all time, with an estimated won-lost record of 131-35 and an ERA of 1.80 in nearly 1,500 innings of work. He struck out 1,565 batters and walked 240. Schwamb once said, “I was a lousy gangster, but I was a great pitcher.”35 He certainly was, at least at San Quentin and Folsom.

Back in Los Angeles, Blackie learned how to navigate the complicated freeway system of an ever-growing metropolis. Nearly 2.5 million people were living in the city by 1960. Schwamb found work at a warehouse in Long Beach and got married to Nancy Black in November. He hoped to pitch for the Los Angeles Angels, an expansion franchise set to debut in the American League and which took its name from the city’s former Pacific Coast League team. Frick, though, had suspended Schwamb for one year.

Los Angeles Examiner columnist Bob Hunter wrote several pieces in support of Schwamb, and Frick reinstated the pitcher in early 1961. Blackie signed a deal with the Honolulu Islanders, a Kansas City Athletics affiliate.

That final attempt at professional baseball ended, as it often did for Schwamb, with a subpar won-lost record and other bad stats. He drank less, but in 21 innings, he allowed 27 hits and had a 5.14 ERA with one win and two losses. Professional hitters handled Blackie’s fastball much better than the cons ever did. Even so, Dave Thies, one of the Islanders’ best pitchers, said, “Everybody was cheering that he would go well. He had a demeanor about him that was very likable, no pretense.”36

His body, though, had begun to tire. His legs felt weak, and the Islanders left him behind at spring-training camp in San Bernardino the following March. Blackie’s baseball career was over. Months later, he and Nancy decided to divorce.

Blackie got married again, this time to Judy Norris, in August of 1964. He also worked construction jobs, both in Los Angeles and Sacramento. He still drank, although he told parole agents that he had quit. Judy sued for divorce in the spring of 1969, not long after police threw Blackie behind bars for public drunkenness. In 1971 Schwamb spent two months in LA County Jail and nearly seven months at the Chino minimum-security prison for illegal possession of a firearm.

Jeanette Schwamb picked up her son at the prison gate. A few days later, Blackie began working at a freight company near Los Angeles International Airport. He also began dating his boss, Bea Franklin. The two, along with Bea’s daughter Denise, moved into a trailer home in Palmdale, California, a community in the Antelope Valley on the western edge of the Mojave Desert. Blackie wanted to get married. Bea, though, had soured on matrimony. Her former husband had been abusive, she said. Blackie mulled over one final assault. Wisely, he decided against throwing any punches. “I was on the Dudley-Do-Right kick,” he said. “I probably would have lost her if I’d beat him up or hurt him.”37

Blackie battled numerous health problems. He developed a bad cough from all that cigarette smoking and suffered a serious back injury while on a boat trip with Bea to the Channel Islands. Denise recalled about her stepdad, “He mostly tried to steer me certain ways, not boss me around. He was strict about curfew and who I hung out with. But I could always sit down with him and tell him something.”38

Eric Stone wrote a biography of Schwamb titled Wrong Side of the Wall. Blackie invited Stone into his trailer. The two men spoke for a bit. Soon enough, Schwamb told his guest to leave. Now. “That’s it,” Blackie said. “Get the hell out of here before I (mess) you up.”39

The felon and former ballplayer died December 21, 1989. He was 63 years old. Just a few years earlier, Blackie said to a friend, with clear lament, “I really could have been someone.”40

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted baseball-reference.com.

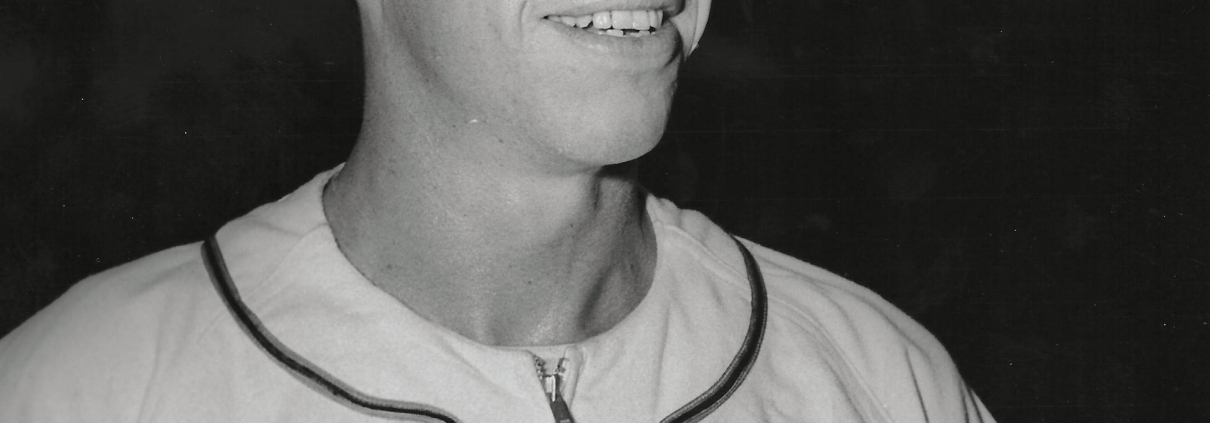

Photo credit: Ralph Schwamb, courtesy of Ed Wheatley.

Notes

1 Eric Stone, Wrong Side of the Wall: The Life of Blackie Schwamb, the Greatest Prison Pitcher of All Time (New York: Lyons Press, 2004), 29.

2 Stone, 18.

3 Stone, 33.

4 Stone, 53.

5 John Buntin, L.A. Noir: The Struggle for the Soul of America’s Most Seductive City (New York: Harmony Books, 2009), 21.

6 Stone, 45.

7 Stone, 63.

8 Stone, 83.

9 Stone, 180.

10 Stone, 182.

11 Harry Mitauer, “Lund’s Double Gives Browns Even Break,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 26, 1948: 17.

12 Robert Morrison, “Browns Gain 10-8 victory for Schwamb,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 1, 1948: 23.

13 Stone, 114.

14 “Early Touchdown, 9th-inning Safety Decide Night Game,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 5, 1948: 21.

15 Neal Russo, “Red Sox Rout Browns, 11-6, Boost Lead over Yanks to Two Lengths,” St Louis Post-Dispatch, September 19, 1948: 57.

16 Glen L. Waller, “Red Sox Win, Gain Ground; Cardinals Bow 3 to 2,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 19, 1948: 48.

17 Stone, 122.

18 Stone, 122.

19 Buntin, 4.

20 Stone, 139.

21 Stone 158

22 Buntin, 9.

23 Buntin, 9.

24 “Schwamb Beats Death Penalty in Buge Slaying,” Long-Beach (California) Press-Telegram, December 21, 1949: 19.

25 “Life Terms Given in Doctor’s Murder,” Los Angeles Times, December 24, 1949: 15.

26 Clifton T. Duffy as told to Dean Johnson, The San Quentin Story (New York: Greenwood Press, 1968), 9.

27 Duffy, 9.

28 Stone, 196.

29 Stone, 202.

30 Stone, 200.

31 Stone, 203.

32 “Chris Rich, Was He the Best Ever?,” Sanquentinnews.com, Was He the Best Ever? (sanquentinnews.com).

33 Stone, 236.

34 Walter Judge, “San Quentin’s Big Leaguer Leaves Prison,” San Francisco Examiner, January 6, 1960: 50.

35 Stone, 86.

36 Stone, 259.

37 Stone 279.

38 Stone, 282.

39 Stone, X.

40 Stone, 283.

Full Name

Ralph Richard Schwamb

Born

August 6, 1926 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Died

December 21, 1989 at Lancaster, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.