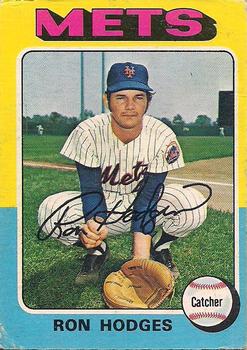

Ron Hodges

In a period of volatility, heartbreak, and disaster for the New York Mets — including the death of owner Joan Payson, the trading of Tom Seaver to the Cincinnati Reds and Dave Kingman to the San Diego Padres on the same day, and last-place finishes from 1977-79 and 1982-83 — backup catcher Ron Hodges provided some stability. Bookending “Ya Gotta Believe” and the birth of the “K Corner,” Hodges spent his entire career in blue and orange, thereby offering constancy for a team steeped in chaos. Players and managers seemed to go through a revolving door that did not stop; there were seven Mets skippers in the 12 years that Hodges played — Yogi Berra, Roy McMillan, Joe Frazier, Joe Torre, George Bamberger, Frank Howard, and Davey Johnson.

In a period of volatility, heartbreak, and disaster for the New York Mets — including the death of owner Joan Payson, the trading of Tom Seaver to the Cincinnati Reds and Dave Kingman to the San Diego Padres on the same day, and last-place finishes from 1977-79 and 1982-83 — backup catcher Ron Hodges provided some stability. Bookending “Ya Gotta Believe” and the birth of the “K Corner,” Hodges spent his entire career in blue and orange, thereby offering constancy for a team steeped in chaos. Players and managers seemed to go through a revolving door that did not stop; there were seven Mets skippers in the 12 years that Hodges played — Yogi Berra, Roy McMillan, Joe Frazier, Joe Torre, George Bamberger, Frank Howard, and Davey Johnson.

Though he broke the barrier of playing 100 games per season just once in a 12-year career with a .240 batting average, Hodges had a highly significant statistic prized by adherents of Moneyball — his on-base percentage was .342.

With resilience honed by Southern sensibility, Hodges displayed what some might call a philosophical approach, neither letting victory inflate his ego nor defeat infect it. On the cusp of the 1981 baseball strike, for example, Hodges said, “If nothing happens in the strike talks, I’ll put everybody in the car and head home to Virginia. There’s not much demand for substitute teachers in summer school. But I used to get $25 to $30 a day during the winter, teaching phys ed [sic] in the middle school — sixth, seventh and eighth grade. Lots of days, I found myself in math and science. When you’re a sub, you take what they have.

“Financially, the strike’s not going to break anybody, unless it lasts. If worse comes to worst, you go out and get a job. You put food on the table. The good Lord gave me talents other than baseball.”1

The strike lasted nearly two months, from mid-June to early August.

A native of Rocky Mount, Virginia — a rural town with a steady population around 4,800 — Ronald Wray Hodges was the seventh of nine children born to Daisy and Tony Hodges. The Hodges patriarch was a furniture maker. At Franklin County High School, Hodges played both sides of the battery, pitching and catching. Frank Ciamillo, his coach, paved the path for Hodges to pursue baseball in college. “He saw talent in me,” says Hodges. “He hauled me to North Carolina to visit colleges to get a scholarship. If I didn’t to that, I probably would have been in the Army and gone to Vietnam.”2

Hodges went to Appalachian State University, where he stayed behind the plate for the Mountaineers. He was drafted three times, but then the Mets offered a small bonus to select him in the free agent draft on January 12, 1972.3 Hodges spent his inaugural year in professional baseball with the Pompano Beach Mets in the Class A Florida State League. Here, he batted .256 with a .380 on-base percentage in 112 games. The following year, Mets skipper Yogi Berra brought Hodges up to Shea Stadium after he played 47 games in AA ball for the Memphis Blues. His .173 batting average in Memphis obscured the on-base percentage of .316. Two Met catchers were on the disabled list, and Berra needed help behind the plate.

About a week after getting called up, Hodges played in his first major league game — a 3-1 Mets victory over the Giants on June 13, 1973. Hodges’s opportunity came because the Mets had two catchers on the disabled list. The Mets’ new backstop admitted being nervous when the game began but settled down soon after. “He was very composed back there. I shook him off maybe 25 percent of the time,” Mets ace Tom Seaver said after one game.4

Hodges became a thorn in the side of Atlanta Braves hurler Ron Schueler about three weeks later, when he punched a 9th inning single to break up a no-hitter. Mets second baseman Felix Millan hit a two-out single for the team’s second and last hit of the night. The Braves won 2-0.5

With six weeks left in the season, the Mets stood at 53-67. Then, relief pitcher Tug McGraw became a highly significant figure in Mets lore. “Around this time, Mets chairman M. Donald Grant decided it was time to give the team a pep talk,” baseball historian David Ferry recounted. “Grant assured the ballclub the front office still had faith in the players and felt the Mets would come around if they only believed in themselves. Those words were seconded by an overenthusiastic McGraw, who interrupted the speech by screaming, ‘Yeah, that’s right, YA GOTTA BEEELIEEEEEEEVE.’”6

Shea Stadium seemed cursed, though. Players crowded the disabled list, including shortstop Bud Harrelson, outfielder Cleon Jones, and catcher Jerry Grote. Hodges got moved from Memphis when the Mets put third-string backstop Jerry May on the disabled list.7

During the 1973 pennant race — when McGraw’s mantra echoed throughout the Mets locker room, Shea Stadium, and the hearts of the Flushing Faithful — Hodges first etched his name in Mets lore on September 20, in a 13-inning contest that came to be famous for the “Ball on the Wall” play.

In the top of the 13th inning, the Pirates had Richie Zisk on first base with two outs against Mets hurler Ray Sadecki. Dave Augustine pounded a fly ball to the left field bullpen fence, just shy of being a home run. The ball rebounded off the top of the fence and straight into the glove of Jones, who fired it to third baseman Wayne Garrett, who threw it to Hodges. Sprinting from first base, Zisk slid into home plate but could not avoid Hodges’s tag. In the bottom of the 13th, Hodges capped his defensive brilliance with a game-winning single that scored John Milner from second base for a 4-3 triumph.

Another win followed, putting the Mets in first place, where they remained to,win the National League East pennant with an 82-79 record. “The pennant drive in 1973 was just awesome,” Hodges said. “The stadium was packed for every game. New York felt like home. It was good to be there.”8

The Mets beat the Cincinnati Reds in the NL playoffs — taking all five games to defeat the Big Red Machine — then lost the World Series in seven games to the dynastic Oakland A’s, which won three consecutive World Series from 1972-1974. Hodges drew a walk in his only plate appearance, as a pinch hitter.

In his rookie season, Hodges played in 45 games and racked up a .260 batting average with a .314 on-base percentage. “Playing in that ’73 season with the pennant drive in September is my favorite memory of my baseball career,” Hodges said.9

Knowing that New York City can offer culture shock to any outsider, whether from Rocky Mount, Rochester, or Ronkokoma, Mets skipper Berra tapped relief pitcher Phil Hennigan to guide the rookie through the Big Apple and, most importantly, make sure he got to Shea Stadium on time. “I stayed at the Travellers Hotel by LaGuardia [International Airport] that first year and after I got married, my wife and I found places to rent on Long Island,” Hodges said.10

Though Hodges was not an everyday player, this did not diminish his commitment. “He was a very solid guy who did what needed to be done,” recalled batterymate Jon Matlack, the 1972 National League Rookie of the Year. “Mets fans are very aware of how much energy you put into the game and they understand that they get the best that you have to give. When Ron played, I was confident that we were prepared to go to war. He was quiet and steady. His left-handed bat was also a plus. There was an air of confidence about him, which I found pleasant, and he gave the impression that he knew what to do. Between Ron and myself, we talked before the game, came up with a basic plan, and followed it until things changed. If he had a suggestion, you would listen to it. I respected what he had to say.”11

Pitchers and catchers have a relationship bordering on telepathic. They must think together as one unit, with a pitcher rarely shaking off a catcher’s sign. Before computers became mainstream, catchers and their batterymates kept information about the opposition in their memory, occasionally chronicling them in notebooks. “We had meetings before every game to go over scouting reports and past things we remembered about hitters,” Hodges said. “The National League hitters were so good. The Phillies had Greg Luzinski and Mike Schmidt. The Dodgers had Steve Garvey. The Reds had Pete Rose and Tony Perez. The Pirates had Al Oliver. The Braves had Dale Murphy.”12

Hodges saw more playing time in 1974, ending the season with 59 games played, .221 batting average, and .310 on-base percentage. The Mets plummeted to a 71-91 record, then bounced back in 1975 to finish the season at 82-80. 1975 was split between AAA and the majors for Hodges — 95 games for the Tidewater Tides of the International League and nine for the Mets. With Tidewater, he batted .266 with a .372 OBP. That year, the Tides won the Governors’ Cup — the International League championship.

While the Mets showed promise in 1976, with an 86-76 record, 1977 proved to be a year of epic disappointment. As the Yankees captured melodrama, excitement, and a return to glory by winning the World Series, New York’s other team endured the unthinkable — on June 15, 1977, the Mets traded their touchstone, Tom Seaver, to Cincinnati for Doug Flynn, Pat Zachry, Dave Henderson, and Dan Norman. In addition, Kingman — a career .236 hitter but always a threat to bash a home run ball onto the Long Island Expressway — was shipped to San Diego that same evening for Bobby Valentine and Paul Siebert.

“The front office thought that by unloading veteran superstars they could get more in return to help us win,” Hodges said.

Such was not the case. The Mets went 64-98 in 1977; 66-96 in 1978; 63-99 in 1979; 67-95 in 1980; 41-62 in the strike-shortened season of 1981; 65-97 in 1982; and 68-94 in 1982.

When the Payson family sold the Mets at the beginning of the ’80 season — five years after the death of original owner Payson — to Nelson Doubleday and Fred Wilpon, it was a chance to wipe the slate clean of past misdeeds on the field and in the front office. Never complaining and always blunt, Hodges said, “I’ve seen a lot of good men come and go.”13 That season, it seemed as if the Mets were cursed. The team’s marketing slogan “The Magic Is Back” garnered giggles rather than ovations.

“My favorite managers were Yogi and George Bamberger,” Hodges said. “Yogi asked for me to be called up to play in the majors. George gave me the opportunity to start on a regular basis. As a backup, I had to learn how to come in off the bench. When I went back to Tidewater in 1975, I made a decision to be a backup in the majors rather than a starter in the minors. Shea Stadium was great to play in. I also liked playing in Atlanta because we had friends who showed up for the games there and also in Pittsburgh. Other than the Shenandoah Valley, San Diego was the prettiest place that I saw when I played.”14

Staying mentally and physically sharp can be a challenge for a major-leaguer sitting on the bench for 100 games or more during a season. “It’s extremely tough to come off the bench to play in the game or pinch hit. There’s a huge adrenaline rush,” Hodges recalled. “Early in my career, I started to shake and my heart beat faster. I would take deep breaths to relax. It took a long time to learn how to not be overly excited. It was a lot tougher coming out of the bullpen instead of the dugout. When you’re in the dugout you have all this noise at home plate and you’re closer to the action. Later, I learned to sit in the dugout, even though it sometimes meant going back to the bullpen to warm up a relief pitcher. Even if you’re not playing, you have to be aware of what’s going on in the game.”15

Ability to remain focused gave Hodges membership in “Bambi’s Bandits,” a group of veterans favored by Bamberger in difficult situations, albeit not every day; Hodges played 80 games in 1982. “Bambi’s Bandits” are described by a Mets historian as follows:

“The backup catcher who’d been here forever: Ron Hodges.

“The sure-handed caddy to a defensively disinterested lumbering slugger: Mike Jorgensen, who backed-up first baseman Dave Kingman, who returned in 1981.

“The cursed with versatility utilityman: Bob Bailor.

“The grumbly fourth outfielder: Joel Youngblood.

“The sweet-swinging pinch-hitter deluxe: Rusty Staub.”16

Hodges was behind the plate on Opening Day in 1983, a highly significant occasion for Mets fans — Tom Seaver, closer to 40 years old than 30, returned to the Mets. “Seaver asked for me to catch his first game back because he wanted a veteran catcher,” Hodges said.17 Once again, fans rejoiced at the pure concentration, right knee dirtied by the huge stretch of the legs, and possibilities of strikeouts when Seaver released his pitches. A marquee value player heading towards the sunset of his playing days, Seaver went 9-14 in 1983.

“The introduction of the starting lineup was made at 1:20. After the eighth batter, Catcher Ron Hodges, was introduced, Public Address Announcer Jack Franchetti said simply, ‘Batting ninth and pitching, now warming up in the bullpen, Number 41.’ No name, just the number. The cheering began,” wrote Steve Wulf in Sports Illustrated.18

In 1983, Hodges became the regular catcher for the Mets, playing in 110 games because of repeated injuries to first-line catcher John Stearns. 1983 was the only season when Hodges cracked the 100-game barrier. “Do I feel cheated by 10 years as a sub? I don’t want to feel cheated. But I’d be lying if I said I never felt that way,” Hodges said at the time.19

Hodges saw the glimmer of a new dawn in 1984 after several dark years for the Mets franchise. Two standouts would eventually lead the team to postseason glory — Dwight Gooden and Darryl Strawberry. “They were pure athletes,” Hodges said. “Gooden had long arms, an awesome fastball, and a great curveball. He let runners steal with no outs and then just struck out the next three.”20

After the season, Hodges hung up his cleats, finishing his career with 666 games, .240 batting average, .342 on-base percentage, and .322 slugging percentage. “My wife and I had three sons and another on the way when I retired. When my agent sent out letters, I didn’t get picked up. So I moved back home to Rocky Mount and became a realtor, selling commercial, industrial, and personal real estate around Smith Mountain Lake. I retired in 2017 after 30 years in real estate,” he said.21

Baseball runs through Hodges’s bloodline to his four sons. Each played in college: Riley was an All-American catcher at Ferrum College, transferring from VMI after one semester; Gray graduated from Virginia Tech; Nat graduated from Radford University, transferring from Ferrum after two years; and Casey was an All-American at Mount Olive College, transferring from Radford after two years. Mount Olive won the 2008 national championship in the game that Casey pitched.

Casey played in the Braves’ minor-league system for two years, then another two years in independent baseball.

Hodges’s career spanned the emotional spectrum for Mets fans — excitement during a surprise pennant race, dejection caused by sub-.500 won-lost records, hope ignited by Gooden and Strawberry in 1984. Every April 15th, major league players all wear No. 42 to honor Jackie Robinson on the anniversary of the date that he broke the color line in 1947. Mets fans joke that it’s Ron Hodges Day because he, too, wore No. 4222. The comments are made out of affection, not derision. Hodges, in a time that tested the endurance of Mets fans, conveyed familiarity. It was not unusual to see Hodges on Kiner’s Korner — a postgame television show hosted by Mets announcer Ralph Kiner — to recap an amazing defensive play or key hit. One stands out for Hodges — a collision at home plate with Braves slugger Bob Horner in a 1983 game. “My neck still hurts. Horner came down hard but I held the ball,” Hodges said.23

Whether substituting, starting, or pinch hitting, Hodges filled the role needed at any given time, without fanfare or celebration. He was a gritty player who defined toughness, exemplified by the Horner play. Because Hodges spent all 12 years of his MLB career in a Mets uniform, he became — and endures as — synonymous with the team.

For players in the first 40 years of the Mets’ existence, only Ed Kranepool spent more time than Hodges in a Mets uniform — 18 years. “I really enjoyed my 12 years in New York,” Hodges said. “When you look back on it, I played baseball for a living. Who can argue with that?”24

Last revised: March 14, 2018

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by David Lippman and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Joseph Durso, “For Two Average Players, Baseball Strike Brings Uncertainty, The New York Times, June 15, 1981.

2 Telephone interview with Ron Hodges, January 3, 2018.

3 ultimatemets.com

4 Joseph Durso, “Mets Turn Back Giants, 3-1,” New York Times, June 14, 1973.

5 Joseph Durso, “Mets Escape No-Hitter in 9th, but Lose by 2-0,” The New York Times, July 7, 1973.

6 David Ferry, Total Mets: The Definitive Encyclopedia of the New York Mets First Half-Century (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2012), 28.

7 Ibid., 27.

8 Telephone interview with Ron Hodges, January 16, 2018.

9 Telephone interview with Ron Hodges, January 3, 2018.

10 Ibid.

11 Telephone interview with Jon Matlack, December 26, 2017.

12 Telephone interview with Ron Hodges, January 16, 2018.

13 Steve Wulf, “The Mets…The Magic Is Bakc,” Sports Illustrated, June 2, 1980.

14 Telephone interview with Ron Hodges, January 3, 2018.

15 Telephone interview with Ron Hodges, January 16, 2018.

16 Greg Prince, “Once in a Blue Monell,” faithandfearinflushing.com, July 7, 2015.

17 Telephone interview with Ron Hodges, January 3, 2018.

18 Steve Wulf, “It Was A Terrific Homecoming,” Sports Illustrated, April 18, 1983.

19 Joseph Durso, “Hodges Gets Shot In Mets’ Spotlight,” New York Times, April 1, 1983.

20 Telephone interview with Ron Hodges, January 3, 2018.

21 Ibid.

22 The last New York Met player to wear No. 42 was first basemen Mo Vaughn, from 2002 to 2003.

23 Telephone interview with Ron Hodges, January 3, 2018.

24 Ibid.

Full Name

Ronald Wray Hodges

Born

June 22, 1949 at Rocky Mount, VA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.