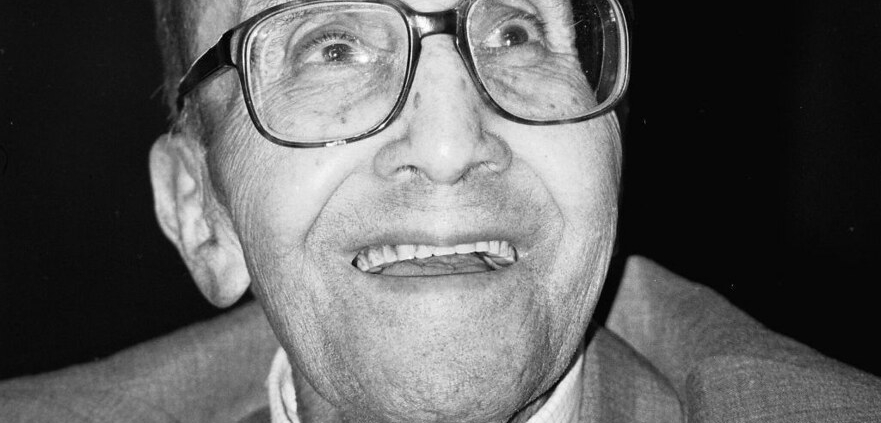

Sam Lacy

When Sam Lacy was growing up in Washington, D.C., he dreamed of becoming a professional baseball player. But in segregated America, the options for talented Black athletes were limited. So, after playing and managing in semipro leagues, he found his calling as a sportswriter. Lacy’s career in journalism lasted more than seven decades. Along the way, he helped open doors for Negro Leagues players in their quest to integrate Major League Baseball; and in 1948, he became one of the first Black members of the Baseball Writers Association of America. He was still working for the Baltimore Afro-American in 1997, when, at nearly 94 years old, he was named the winner of the BBWAA Career Excellence Award (until 2021 known as the J. G. Taylor Spink Award), given for “meritorious contributions to baseball writing.”1 Few baseball writers have ever been more deserving, and few enjoyed such a long and distinguished career.

When Sam Lacy was growing up in Washington, D.C., he dreamed of becoming a professional baseball player. But in segregated America, the options for talented Black athletes were limited. So, after playing and managing in semipro leagues, he found his calling as a sportswriter. Lacy’s career in journalism lasted more than seven decades. Along the way, he helped open doors for Negro Leagues players in their quest to integrate Major League Baseball; and in 1948, he became one of the first Black members of the Baseball Writers Association of America. He was still working for the Baltimore Afro-American in 1997, when, at nearly 94 years old, he was named the winner of the BBWAA Career Excellence Award (until 2021 known as the J. G. Taylor Spink Award), given for “meritorious contributions to baseball writing.”1 Few baseball writers have ever been more deserving, and few enjoyed such a long and distinguished career.

Samuel Harold Lacy was born in Mystic, Connecticut, on October 23, 1903, according to some sources, including his own autobiography. However, recent research, as well as census documents, suggest he was actually born in Washington D.C., circa 1904 or 1905. He was the youngest of four children born to Samuel Erskine Lacy, a notary public2 (also identified in some sources as a researcher in a law firm),3 and his wife Rosa (Bell). It wasn’t until Sam was in his fifties that he learned his mother was a full-blooded Native American, from the Shinnecock tribe, and a member of the Mohawk Nation; but this was never mentioned when he was growing up.4

According to his autobiography, when Sam was two, the Lacy family moved to Washington, D.C., where Sam’s paternal grandparents lived. His grandfather, Henry Erskine Lacy, became D.C.’s first Black police detective.5 Sam was raised not far from Griffith Stadium, then home to the major league Washington Senators. (Fans back then, including Sam, and many sportswriters, often preferred the name Nationals.)6 Among his favorite childhood memories were how much his father loved baseball, and how much he enjoyed reading the newspaper. Young Sam inherited both traits. At Armstrong Manual Training School (later known as Armstrong Technical High School), he played football and basketball, but he was always drawn to baseball and earned acclaim for his pitching skills. The local newspapers covered schoolboy sports, and one sportswriter wrote about “Sam Lacy, the high school hurling ace” who struck out the side against a Howard University freshman team to preserve an Armstrong victory.7 In another game, Lacy helped to defeat intercity rival Baltimore High.8 In addition to playing sports, he covered them for Armstrong’s newspaper,9 although at that time, he did not envision turning that activity into a career.

Because he grew up only a few blocks from Griffith Stadium, Lacy, along with several other neighborhood boys, would often visit the ballpark in the summer to shag fly balls during batting practice. That was how he met some of the Nationals, and ran errands for some of them.10 But as friendly as he was with big-name players like Walter Johnson, it didn’t change the fact that Washington was a segregated city, and Griffith Stadium was no exception: when he wanted to watch a game, he could only do so from the “colored-only section,” out in right field.11 Meanwhile, as a teen, he found that during the summer, he could earn extra money as a vendor, selling merchandise in the stands at Griffith Stadium. He also served as a caddy for golfers at the all-white Columbia Country Club in nearby Chevy Chase, Maryland. Among the men for whom he caddied was Nationals’ secretary-treasurer Ed Eynon,12

After graduating from high school in 1924, Lacy wanted to get a fulltime job in sports: he envisioned coaching a basketball team, or perhaps being a player-manager for a semipro baseball team, but his mother insisted he go to college. To make her happy, he enrolled at Howard University, but while many sources say he graduated, he did not. In his autobiography, he acknowledges that he left after only one year.13 Lacy had already played for a couple of Black semipro teams, including the Washington Black Sox, LeDroit Tigers (a neighborhood team from LeDroit Park, an upwardly-mobile Black neighborhood near Howard University), and the Bachrach Giants. He decided to see if he could become a successful player-manager. But while he enjoyed doing both, it became obvious that a career in Black baseball would not earn him enough money to support a family. He had married in 1927, and he and his wife, the former Alberta Robinson, wanted to have children. They would ultimately have a son, Samuel Howe (better known as Tim), who followed in his dad’s footsteps and became a sportswriter.

In need of a profession that offered a stable income, Lacy gravitated towards journalism, where he could report and write about sports, even if playing was no longer feasible. By 1930, he was working for the Washington Tribune,14 where he covered all the local teams, and wrote a regular column called “Looking ’Em Over with the Tribune.” Gradually, he worked his way up, becoming the paper’s sports editor in 1934.

Like many sportswriters for Black newspapers, Lacy did not just confine himself to which teams won or which players did well. He now had a platform to comment on social trends, including discrimination against Black athletes. In one commentary from early 1934, he remarked upon how white students were often given new and modern athletic facilities, while local Black students were relegated to using outdated and inadequate gymnasiums. Sometimes, he critiqued how Black people were depicted on radio, once taking comedian Will Rogers to task for using the N word during a network radio skit.15 And sometimes he spoke about the effects of racism.

One story Lacy told in a column was about his own father, who had been a passionate fan of the Washington Senators and had taken him to the games for years… until one very unpleasant incident that occurred in 1924, prior to the Senators’ World Series opener against the New York Giants. His dad was standing in the crowd, watching a parade in honor of that event. He was cheering the players as they marched toward the stadium, proudly waving a classic “I Saw Walter Johnson Pitch His First Game” souvenir banner he had gotten in 1907. But as the players approached, Senators’ first-base coach Nick Altrock, well-known as the team’s clown, suddenly threw a “dirty, wet towel” at Mr. Lacy, striking him. Feeling humiliated and angry, he went home and never attended another Senators game.16 (Some sources, including Lacy himself, have told another version of the event, saying that Altrock spat in Mr. Lacy’s face. That is not the way Sam described what happened to his dad in his 1998 autobiography, but it is what he told an interviewer for Sports Illustrated in 1990.17 In either case, his father was deeply hurt by what had occurred, and Sam was affected by it even years later.)

While he kept up with Major League Baseball, Lacy was also one of the many Washingtonians who followed the Negro Leagues faithfully. When he was a player, he knew (and sometimes played against) a number of big names, including the versatile pitcher Martin Dihigo, and star shortstop John Henry “Pop” Lloyd. Now, as a fan, he enjoyed watching stars like Josh Gibson and Satchel Paige. But as Lacy recalled years later, few of the Negro Leagues players he knew in the 1920s questioned why they couldn’t be in the majors. They understood it was how things were, and they put up with the situation, seeing no alternative.18 However, that didn’t stop Black baseball writers like Lacy, along with Wendell Smith, Joe Bostic, Frank “Fay” Young, and others, from speaking out. And in the end, their influence helped to persuade white Major League owners that the time was right to bring in Black players.

As early as 1935, Lacy was using his column in the Tribune to advocate for integration of the major leagues.19 Then, in 1937, he decided to approach some of the owners in person. Lacy first went to Washington Senators’ owner Clark Griffith to suggest that Griffith’s last-place team might benefit from adding some of the Homestead Grays’ players (including such greats as Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, and Cool Papa Bell);20 Griffith was not interested, telling Lacy the “climate wasn’t right” for taking such a step.21 Lacy responded, “The climate will never be right if you don’t test it.”22 It is also worth noting that in addition to the fact that many owners agreed with segregation in principle, some were making money from it: few Negro Leagues owners could afford to buy their own ballpark, and major league owners, including Griffith, derived revenue from renting their parks to Negro Leagues teams when their own teams were out of town.23

By 1939, Lacy’s columns were being published in the Baltimore Afro-American (back then, the newspaper had offices in both Washington and Baltimore, as well as several other cities). That August, Lacy interviewed some Negro League players, asking them how they felt about the ongoing campaign that baseball writers (and by now, even some fans) were waging to get the major leagues to integrate. He wondered if what the writers wanted was in fact what the players wanted, and he decided to ask some of them. The results showed quite a bit of ambivalence. For example, Vic Harris, player-manager of the Homestead Grays, worried that the major leagues would simply pick off the Negro Leagues’ few biggest drawing cards, leaving the rest of the players — who were good, but not great — to struggle to make a living when large crowds no longer showed up for the games. Felton Snow, player-manager of the Baltimore Elite Giants, worried that some of the players might not behave in a responsible manner if they were to receive big salaries, thus giving Black players a bad name.

Jud Wilson, third baseman of the Philadelphia Stars, wasn’t worried, however. He said it was pointless to even discuss this, since it wasn’t going to happen at any time soon. As he saw it, the major leagues were dominated by southerners, loyal supporters of segregation, so no change was likely, no matter how much certain people advocated for it. Further, he doubted that integration would be good for Black players, since so many cities did not have integrated hotels or practice facilities, and even most ballparks were segregated. What was needed, Wilson said, was a “universal movement” for change, and in 1939, he did not see such a movement occurring. Newark Eagles player-manager Dick Lundy focused the conversation on what he saw as the flaws in the Negro Leagues’ business model: he believed the league needed stronger ownership (with owners who had the money to invest in their teams) and better publicity. He discussed some other problems he had observed, but the bottom line was that, rather than worrying about if and when integration might come, he believed there should be a greater effort to improve what there already was; running the Negro Leagues in a more professional way was the number one thing on his list. He said he had heard promises for 25 years that this would happen, but thus far, it hadn’t. He concluded by saying that if the Negro Leagues were perceived as a stronger organization, they could “DEMAND rather than SOLICIT recognition.” 24

Whether those responses disappointed Lacy or not, he seemed very willing to quote them, and to get his readers engaged in the conversation about whether integration was good for Black players or not. After integration occurred, Lacy himself became the object of scorn from some of the owners, who blamed him for the ultimate end of the Negro Leagues.25 But when he was criticized, he would respond, “The Negro Leagues were an institution, but they were the very thing we wanted to get rid of because they were a symbol of segregation.”26 Despite continued resistance from white major league owners and ambivalence from some Negro Leagues players, Lacy was undeterred; he would continue insisting that the time was right to give Negro Leagues players their chance. His efforts to discuss the situation with major league baseball executives were frequently thwarted, Then-baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis was among those who refused to even meet with him.27 And although he and other Black baseball writers continued to advocate for change, it would not be until 1947 that the first Black baseball player, Jackie Robinson, finally got the opportunity Lacy and others had talked about for years.

Throughout the 1930s, as he had done since childhood, Lacy took on numerous jobs, even while he was writing about sports for the Tribune. He continued to coach or manage local semipro and schoolboy teams. Sometimes he even umpired local baseball games. He also tried his hand at radio. Due to segregation, there were few Black announcers on the air, and even fewer Black sportscasters (the first was Jocko Maxwell, circa 1930 in New York City), but Lacy was able to get a sports program on D.C. station WOL for a few months in 1935.28 Local baseball fans were already very familiar with his voice; throughout much of the 1930s, he was a public address announcer at Griffith Stadium. Whenever the Homestead Grays played Negro Leagues games there, Lacy was the one who introduced the players, called the plays, and kept the fans informed about what was going on. He also had an assistant, a young man named Harold (later known as Hal) Jackson, who eventually took over the stadium announcer role.29 Jackson went on to a successful career as a broadcaster. This was just one of many times in Lacy’s life when he served as a mentor. Another young man who learned a lot from him was an up-and-coming reporter named Arthur “Art” Carter, whom he hired at the Tribune in 1937. Carter subsequently went on to a long career at the Afro-American.30

Black sportswriters of that time were expected to cover Black athletes from many sports, both local and national; thus, Lacy’s beat included Black athletes in baseball, track, boxing, basketball, and college football. He also gained a reputation for pursuing the facts, even if what he wrote was sometimes controversial. For example, in October 1937, a story he wrote about a college football player proved contentious. Lacy’s intention was to expose racism in college athletics, and to point out the hypocrisy of the discriminatory policies many conferences utilized. He wrote about a star college quarterback, Syracuse University’s Wilmeth Sidat-Singh, who was frequently identified in print as Indian and referred to as “the Manhattan Hindu” by reporters. But Lacy had discovered that the young man was not from India at all. Rather, he had been born to Black parents in Washington, D.C. After his father died, his mother remarried, and Wilmeth was adopted by her new husband, an Indian surgeon from New York.31 This mattered because many colleges, even up north, adhered to a “gentlemen’s agreement” that they would not play their Black athletes against southern teams. And Wilmeth Sidat-Singh, despite having an Indian last name, was actually Black. When Lacy’s story broke, Syracuse University was scheduled to play against the University of Maryland, which was a member of a conference that did not play against Black athletes. Suddenly, Sidat-Singh was pulled from the starting lineup, and he lost his opportunity to play in a big game. Syracuse lost, and Lacy wrote, “An undefeated football record went by the boards here today as racial bigotry substituted for sportsmanship… Wilmeth Sidat-Singh, a Negro who had won his way into the hearts of his Syracuse teammates and student associates, was denied the privilege of playing in today’s ‘contest’ when Maryland University [sic] officials learned his nationality and demanded removal…”32

Sometime in 1940, Lacy left the Afro-American to work at the Chicago Defender for several years as an assistant editor. By some accounts, he clashed with sports editor Frank A. “Fay” Young — they were two men with forceful personalities, and perhaps such clashes were to be expected.33 But Lacy simply explained in his autobiography that the Defender wanted him to cover news, rather than sports, and that was not where his heart was.34 Another reason he decided to leave occurred in 1943. Lacy thought he had finally persuaded the owners to hear a presentation about the case for Black players in Major League Baseball; but instead of letting him make that case, the Defender sent someone else — actor Paul Robeson. The Defender’s management thought the well-known, but outspoken, Black entertainer would generate more publicity for the cause than a sportswriter.35 But the presentation was unsuccessful. Frustrated, Lacy returned to the Baltimore-Washington area, where he rejoined the Afro-American as Sports Editor; he would remain there for the next five decades.

By 1944, Lacy was also back on the radio, doing a Sunday morning baseball-themed program with Harold Jackson on station WINX; they interviewed Negro Leagues players and discussed recent Homestead Grays’ games.36 Meanwhile, Lacy continued advocating for baseball’s integration. In March 1945, he wrote letters to every major league owner, suggesting they form a committee to study the possibility of integrating the game. A committee was formed, but only on paper — it never had any meetings.37 On the other hand, momentum for change was finally building: in that post-World War II era, even some of the white-owned mainstream newspapers like the New York Times were coming out in favor of the integration of baseball.38 And when Branch Rickey announced that Jackie Robinson had been signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers, the Afro-American put Lacy on a new beat: covering all things Jackie Robinson. At the time, it was considered the biggest sports assignment for any Black reporter, and Lacy would soon distinguish himself.

In late February 1946, Robinson reported to the AAA Montreal Royals spring training camp in segregated Daytona Beach, Florida. Lacy was there to cover him, but they also ended up traveling together and becoming friends. In much of Florida, Black players like Robinson were forbidden from staying in the same hotels or eating in the same restaurants with their Royals teammates. Robinson and Lacy, along with another Black Montreal prospect, pitcher Johnny Wright, stayed in private homes, as was often necessary for Black people traveling in the south. But despite enduring the obstacles and the unequal treatment, Lacy was gratified to see history finally being made. On March 8, Robinson played seven innings in a scrimmage game. For Lacy, this was more than just a practice. “It was the first time in history that a colored player had competed in a game representing a team in modern organized baseball.”39 And in his Afro-American column, he admitted his own nervousness whenever Robinson played: “I was constantly in fear of his muffing an easy roller under the stress of things,” he wrote, expressing his hope that the young man would give his critics no excuse to dismiss him. But in the end, Robinson did not disappoint, even under difficult conditions.40

Covering Robinson was a challenge for Lacy and other black sportswriters assigned to the “Robinson beat.” Southern segregationists made it clear they were not welcome: for example, a cross was burned on the lawn of the boardinghouse where they stayed before an exhibition game in Macon, Georgia.41 Lacy was often denied entrance to the press box, sometimes told he had to report from the stands or from the dugout. In one instance, at Pelican Stadium in New Orleans, he was told he could only cover the game from the roof. He climbed all the way up there, and to his surprise, he was soon joined by several white sportswriters, including Dick Young of the New York Daily News, who wanted to show him that they accepted and respected him. Of course, they didn’t want to embarrass him, so instead they claimed they were just there to get a suntan. But Lacy understood, and he appreciated the gesture.42

Even after Robinson made the major leagues and Lacy’s presence in the press box was no longer forbidden, discrimination against Black players and Black sportswriters persisted. In fact, long after 1954’s Brown vs. the Board of Education decision began the process of ending segregation, many parts of the country remained segregated well into the late 1960s. On many road trips, Lacy and the Black players still had to stay in inferior accommodations; they couldn’t eat in certain restaurants; taxis would not stop for them, forcing them to walk to the ballpark; and they were taunted by some of the fans. But Lacy never made the story about himself. He always focused on the games and the players. And he maintained his reputation for being fair. After Jackie Robinson won the Rookie of the Year award in 1947, he reported to 1948 training camp late, and out of shape. As much as Lacy respected Robinson (and vice versa), the sportswriter took the young man to task, as he would any player. He criticized Robinson for having a “lackadaisical attitude” and “laying down on the job.” Robinson, determined to prove Lacy wrong, responded almost immediately, getting back into shape and resuming his excellent play.43 And although most of Lacy’s reporting was on the “Robinson beat,” he still covered the Negro Leagues sometimes,44 and he kept in touch with many of the players he knew in Washington and Baltimore.

By 1948-1949, as a few other clubs signed Black players, in both the major and minor leagues, he was able to cover them. But although Lacy was now well known at many ballparks, one door remained closed: the Baseball Writers Association of America was still an all-white organization. Lacy could sit in the press box (in some cities), but like his colleague Wendell Smith, he was not a member. The excuse some chapters used when excluding the Black writers was that most of their papers were weeklies, and not dailies. By the late 1940s, even some white members had come to believe this was a distinction without a difference, and they said so.45 After all, the Black reporters worked just as hard and covered just as many games in the course of a week. In 1948, Lacy became one of the Baseball Writers’ first black members, paving the way for other Black writers. (Lacy asserted that he was the first,46 and other sources agreed;47 but some sources have said that Wendell Smith was first.)

By now, Lacy was receiving offers from mainstream white publications, but he remained at the Afro-American. He liked the work, and he liked the Baltimore-Washington area. In 1952, his personal life underwent some turmoil, as his first marriage ended in divorce (by his own admission, he was not home much, and at times, he liked to gamble). He remarried several years later and credited his new wife Barbara with being a stabilizing force in his life and making him a more responsible person.48 (Barbara’s daughter Michaelyn became Sam’s stepdaughter.)

Long after baseball had integrated, Lacy continued to advocate for more respect for Black athletes, no matter which sports they played. He covered six Olympic Games; he wrote about Black tennis champions like Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe; he covered track and field star (and Olympian) Wilma Rudolph, and Black golfer Lee Elder, as well as numerous boxers, and football and basketball players. Sports were his passion, and he was still reporting on them for the Afro-American well into his late 90s. In fact, several days before he died on May 8, 2003, at age 99, he had filed his next column — just as he had done for so many years.49 For the last three years of his life, his son Tim had driven him to the office,50 but that was the only accommodation he made to his advancing age. Lacy’s death was front page news at the Baltimore Sun,51 and newspapers from coast to coast carried the story; many also carried tributes. More than 200 mourners attended Lacy’s funeral at the Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Washington D.C., including Baltimore’s then-mayor Martin O’Malley, numerous sportswriters and sportscasters who had worked with him (or been mentored by him), and local pro athletes, including former Baltimore Colts’ running back Lenny Moore.52 He was buried at Lincoln Memorial Cemetery in Suitland, Maryland.

Lacy won a long list of awards and honors during his career: In January 1985, he was inducted into the Maryland Sports Media Hall of Fame.53 In July 1991, he received a lifetime achievement award from the National Association of Black Journalists.54 In 1997, Major League Baseball commemorated the 50th Anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s breaking baseball’s color barrier; Lacy threw out the first pitch on April 15, 1997, at the game between the Orioles and the Twins.55 In October 1997, the Baseball Writers Association of America named him the winner of the BBWAA Career Excellence Award (then known as the J. G. Taylor Spink Award). In April 1998, he won the Red Smith Award from the Associated Press Sports Editors, for “major contributions to sports journalism.”56 And in July 1998, he was inducted into the Writers Wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York.

Reflecting on Lacy’s life and legacy, Afro-American publisher John Jacob “Jake” Oliver said, “Sam Lacy was everybody’s father, everybody’s uncle, everybody’s coach. He was the man who taught a whole generation of our writers here at the [Afro-American newspapers] how to be journalists … he probably [knew] more history about what 20th century African-American sports was about than anyone else … we can never say enough about Sam Lacy …”57

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Malcolm Allen for his suggestions on the initial draft of the biography, which was also reviewed by Norman Macht and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team. The author also wishes to thank librarians Herbert Rogers and Christine Iko of the Enoch Pratt Free Library in Baltimore for their assistance.

Sources

In addition to the sources mentioned in the Notes, the author referred to documents on Ancestry.com, as well as using information from several SABR bios.

Photo credit: John Mathew Smith, Flickr.com. Creative Commons License, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Notes

1 Frank Litsky, “Sam Lacy, 99; Fought Racism as Sportswriter,” New York Times, May 12, 2003: B7.

2 John C. Walter and Malina Iida, Editors, Better Than the Best: Black Athletes Speak, 1920-2007 (Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press, 2010): 3-4.

3 Chris Lamb, Conspiracy of Silence: Sportswriters and the Long Campaign to Desegregate Baseball (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2012): 57.

4 Sam Lacy, with Moses J. Newsom, Fighting for Fairness (Centerville, Maryland: Tidewater Publishers, 1998): 13-14.

5 Sam Lacy, with Moses J. Newsom: Fighting for Fairness: 15.

6 Sam Lacy, with Moses J. Newsom: Fighting for Fairness: 24.

7 “Armstrong Manual Training School,” Washington D.C. Evening Star, May 6, 1923: 26.

8 “Armstrong Manual Training School,” Washington D.C. Evening Star, May 12, 1923: 24.

9 Steve Katz, “Sam Lacy Traveled Rough Road with Black Athletes,” Baltimore Sun, August 17, 1980: C5.

10 Marilyn McCraven, “Writing on the Wall,” Baltimore Sun, April 1, 1997: 1F, 5F

11 Barry Horn, “Sam Lacy: Honoring the Voice of Change,” Burlington (Vermont) Free Press, April 26, 1998: 4C.

12 Steve Katz, “Sam Lacy Traveled Rough Road with Black Athletes,” Baltimore Sun, August 17, 1980: C5.

13 Sam Lacy, with Moses J. Newsom, Fighting for Fairness: 24.

14 Litsky, “Sam Lacy”: 99.

15 Sam Lacy, with Moses J. Newsom, Fighting for Fairness: 31.

16 Sam Lacy, with Moses J. Newsom, Fighting for Fairness: 25.

17 Frederick J. Frommer, You Gotta Have Heart, (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2020): 56.

18 Quoted by Jim Reisler, in Black Writers, Black Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, revised edition, 2007): 15.

19 Frederick J. Frommer, You Gotta Have Heart: 56.

20 “Thomas Mulloy, “A Picture of Sam Lacy,” Cleveland Call & Post, May 6, 2009: C1.

21“Quoted by Jim Reisler, in Black Writers/ Black Baseball: 15.

22 Quoted by Howie Evans, “75th Anniversary of Negro Baseball League Celebration Slated,” (New York City) Amsterdam News, December 2, 1995: 48.

23 Bob Luke, The Baltimore Elite Giants: Sport and Society in the Age of Negro League Baseball (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009): 5-6.

24 Sam Lacy, “Players Indifferent About Entering Major Leagues,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 5, 1939: 19.

25 “Thomas Mulloy, “A Picture of Sam Lacy,” Cleveland Call & Post, May 6, 2009: C1.

26 Litsky, “Sam Lacy: 99.

27 Charlie Vascellaro, “How Sam Lacy Helped Integrate Major League Baseball,” Baltimore Sun, April 22, 2013: A17.

28 Radio Listings, Washington Tribune, November 19, 1935: 8.

29 Hal Jackson, with James Haskins, Hal Jackson: The House that Jack Built, (New York: Amistad Press, 2001): 24-25.

30 Lawrence A. Still, “A Pioneer of the Black Press: Remembering Arthur Carter–War Reporter, Civil-Rights Veteran,” Washington Post, June 26, 1988: C5.

31 “Lacy’s Scoop Derailed History at the University of Maryland,” Baltimore Afro-American, February 22, 2017: https://www.afro.com/sam-lacy-scoop-derailed-history-university-maryland/

32 Ron Fimrite, “Sam Lacy: Black Crusader,” Sports Illustrated, October 29, 1990: https://vault.si.com/vault/1990/10/29/sam-lacy-black-crusader-a-resolute-writer-helped-bring-change-to-sports

33 Jim Reisler, Black Writers/Black Baseball: 15.

34 Sam Lacy, with Moses J. Newsom, Fighting for Fairness: 44.

35 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Greatest Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008): 41.

36 See for example, Advertisement in the Washington Tribune, June 24, 1944: 29.

37 Chris Lamb, “Heavy Hitters for Integrated Baseball: Sportswriter Sam Lacy and Wendell Smith Reported on Jackie Robinson’s Journey to the Major Leagues,” Baltimore Sun, February 18, 1996: 7F.

38 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Greatest Experiment: 3.

39 Quoted by Chris Lamb, Heavy Hitters: 7F.

40 Sam Lacy, “Looking ‘Em Over,” Baltimore Afro-American, March 16, 1946: 25.

41 Ron Fimrite, “Sam Lacy: Black Crusader”: https://vault.si.com/vault/1990/10/29/sam-lacy-black-crusader-a-resolute-writer-helped-bring-change-to-sports

42 Barry Horn, “Sam Lacy”: 4C.

43 Mike Klingaman, “Hall of Fame Opens Door for Writer,” Baltimore Sun, July 26, 1998: 1A.

44 Sam Lacy, “Homesteads Drop 9-6 Tilt to Elites,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 24, 1948: 29.

45 Vince Johnson, “Jim Crowism in the Press Box,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, July 22, 1949: 17.

46 Sam Lacy, with Moses J. Newsom: Fighting for Fairness: 99-100.

47 Vince Johnson, “Jim Crowism”: 17.

48 Sam Lacy, with Moses J. Newsom, Fighting for Fairness: 27.

49 Mike Klingaman, “Pioneering Sportswriter Fearless,” Chicago Tribune, May 11, 2003: section 3:1

50 Kenny Lucas, “Lacy Eulogies Hail Champion,” New York Daily News, May 17, 2003: 56.

51 Mike Klingaman, “Crusading Sports Journalist, Integration Pioneer, Dies at 99,” Baltimore Sun, May 10, 2003: 1A.

52 Derrill Holly, “Hundreds Attend Writer’s Funeral,” Charlotte Observer, May 17, 2003: C12.

53 Doug Brown, “28 Football Players to be Honored for their Courage Playing in Pain,” Baltimore Sun, January 24, 1985: C3.

54 Alex Dominguez, “Pioneer black sportswriter cleared a path for others,” Baltimore Sun, August 26, 1991: 4B.

55 Roch Kubatko, “Barney, Other Fans Say Thank You,” Baltimore Sun, April 16, 1997: 5D.

56 “Afro-American’s Lacy Presented Smith Award for Sports Journalism,” Baltimore Sun, April 19, 1998: 2C.

57 John Jacob “Jake” Oliver (The HistoryMakers A2003.273), interviewed by Larry Crowe, November 12, 2003, The HistoryMakers Digital Archive. Session 1, tape 6, story 4, John Jacob “Jake” Oliver talks about sports journalist, Sam Lacy.

Full Name

Samuel Harold Lacy

Born

October 23, 1903 at Mystic, CT (US)

Died

May 8, 2003 at Washington, DC (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.