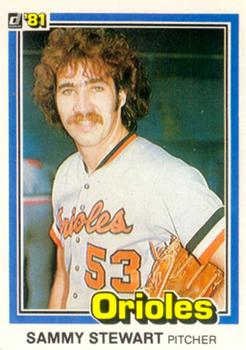

Sammy Stewart

When Sammy Stewart was asked by the National Baseball Hall of Fame what he considered to be his most outstanding achievement in baseball, he quite justly answered that it was the rookie record he set in 1978 when he threw seven consecutive strikeouts in his major-league debut. No rookie has matched Stewart’s totals. It was September 1, 1978, at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium, facing the Chicago White Sox. He got through the first inning, despite a leadoff single, his own error, and a wild pitch. The O’s scored four times in the bottom of the first. Then Stewart struck out the side in the second, struck out the side in the third, and whiffed the first batter in the fourth. Mike Squires spoiled the streak by popping up to left field. Stewart and the Orioles won the game, 9-3. It’s a record he still holds.

When Sammy Stewart was asked by the National Baseball Hall of Fame what he considered to be his most outstanding achievement in baseball, he quite justly answered that it was the rookie record he set in 1978 when he threw seven consecutive strikeouts in his major-league debut. No rookie has matched Stewart’s totals. It was September 1, 1978, at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium, facing the Chicago White Sox. He got through the first inning, despite a leadoff single, his own error, and a wild pitch. The O’s scored four times in the bottom of the first. Then Stewart struck out the side in the second, struck out the side in the third, and whiffed the first batter in the fourth. Mike Squires spoiled the streak by popping up to left field. Stewart and the Orioles won the game, 9-3. It’s a record he still holds.

In his only other 1978 appearance, four weeks later to the day, he lost a tough 3-2 game to the Detroit Tigers. Stewart had allowed two earned runs, but an error by his center fielder cost the game.

Over the course of 10 seasons and 359 big-league games, the first eight with Baltimore, Stewart won 59 games and lost 48, with an earned-run average of 3.59. He sometimes suffered some pretty bad luck – in 1981, his 2.32 ERA was second in the American League1 but his record was 4-8 (and that for an Orioles team that finished second in the AL East, just two games out of first place.)

He was a junior, born to Samuel Lee Stewart Sr. and the former Mary Faye Wardrup on October 28, 1954, in Asheville, North Carolina. The boy who became known as “The Throwin’ Swannanoan” grew up in that North Carolina community, attending eight years of elementary school and Charles D. Owen High School. He completed two years at Montreat Anderson Junior College.

Stewart was selected by the Kansas City Royals in the June 1974 free-agent draft, but not until the 28th round. He elected not to sign that year, but did so as a nondrafted free agent when approached by Baltimore scout Rip Tutor, signing on June 15, 1975. The Orioles assigned him to the Bluefield Orioles in Bluefield, West Virginia, in the Appalachian League, a rookie league. He appeared in 18 games, starting in four, and compiled a 3-3 record with an ERA of 6.07 while getting his feet wet for the first time. He was still only 20 years old.

Stewart took full advantage of his first full season in Organized Baseball, pitching in Class A for the Miami Orioles (Florida State League). Throwing 182 innings, he put up a 12-8 record with an earned-run average of 2.42. Climbing two rungs on the ladder in 1977, Stewart was promoted to the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings. He was 0-5, then positioned a bit lower, moved to Double-A and the Southern League’s Charlotte O’s (9-6, 2.08 ERA.) He finished 0-5 (6.33) with Rochester, but that’s where he was reassigned in 1978, and this time he made good, winning 13 and losing 10 with a 3.80 ERA. And at the end of the year, he was given that first start and struck out those seven White Sox one after the other. He wouldn’t see the minor leagues again other than for eight innings with Hagerstown in 1982 and 11⅔ innings in 1987 for Buffalo at the end of his career.

Stewart was a right-hander standing 6-feet-3 and listed with a playing weight of an even 200 pounds. He had married his high-school sweetheart, Peggy Jean Logan, in January 1977. The couple had two children, Colin and Alicia, both born with cystic fibrosis. It was important for him to remain as close as he could to hospitals of quality.

In 1979, Stewart was used primarily in relief – though he won each of the three starts he was given, pitching seven, nine, and eight innings and never giving up more than two earned runs. It was hard to crack manager Earl Weaver’s five-man rotation featuring Mike Flanagan, Jim Palmer, Scott McGregor, Dennis Martínez, and Steve Stone. There were only five starts all season by anyone other than the main five, and Sammy had three of the five.

That rotation carried the Orioles to a division championship, eight games ahead of second-place Milwaukee, and to a pennant, winning the best-of-five American League Championship Series over the California Angels, three games to one. Sammy played no role in the ALCS. He did see action in the World Series, coming on in early relief of Dennis Martínez in Game Four at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium. The Pirates already had three runs in. He gave up one hit, allowing an inherited runner to score from second, but in 2⅔ innings of World Series work was not charged with a run, earned or unearned. The Pirates prevailed in seven games. Stewart came into baseball after the AL adopted the designated-hitter rule, and finished before interleague play. Accordingly, he never had a regular-season at-bat at any point, but he did bat once in the World Series. Jim Bibby struck him out.

The 1980 Orioles had not just one, but two 20-game winners (Steve Stone actually won 25), but they finished second to the Yankees. Stewart posted nearly identical stats to 1979 – again, he started three times, but this time he lost the first of them. His ERA for the year was 3.56 instead of 3.52, negligibly different. He threw one more inning – 118⅔ instead of 117⅔. The only significant difference was that Weaver had him close 20 games, double the year before.

And 1981 wasn’t that much different in some regards. Again, three starts, 112⅓ innings, and the team finishing second to the Yankees. This time all the first three starts were losses, and all in the first half of the year which had been split into two halves due to a midseason players’ strike. The Orioles finished two games behind the division leader in each half and weren’t involved in the postseason at all. This was the year that Stewart finished second in ERA only to Dave Righetti‘s 2.05 among all AL pitchers, with his 2.32 mark – by far the best of his career – but suffered the 4-8 W-L record.2 It was also a year when he almost threw left-handed in a game against the Yankees. “I’ve always been able to throw left-handed pretty good,” Stewart told Albany Times-Union writer Bob Matthews. “Flanny [Mike Flanagan] bet me I’d never try it in a real game, but I came real close.” It was May 26, and the Orioles had a 6-4 lead in the top of the ninth with nobody on. Left-handed hitter Dave Revering was up for the Yankees and the count was 0 and 2. “I turned my back to the plate, bent over, and shifted my glove to my right hand. Then I turned around real quick, and started to gear up for a left-handed pitch. Revering looked stunned and asked for time just as I was at the top of my windup.” Jim Palmer recalled that Orioles pitching coach “Stu Miller had to run out there and stop him.” Glove back on his left hand, Stewart got Revering to foul out to the catcher.3

The following year, Stewart still faced the challenge of cracking the rotation. One of his problems may have been that, despite such a stellar ERA in 1981, he was “too good for his own good … too good at what he does.”4 He was “Mr. Everything” for Weaver – a long reliever, a spot starter, a closer in the days before that was a specialty. Teammate Mike Flanagan really appreciated what Stewart brought to the bullpen: “He comes to the park prepared to pitch seven innings every night. It can be a thankless job,” he added, thinking of the times that Stewart would come into a game with the Orioles already trailing and keep them in the game, eating up innings.5 Miller saw Stewart as offering the team the luxury of having two starting pitchers on most nights – the man chosen to start, and then Stewart himself, who was always ready. “He’d be a starting pitching for at least 24 teams in baseball right now – all except ours and maybe Houston.” Miller told Peter Gammons, “On a good staff, a guy in that role can hold everything and everyone together.”6

“I like long relief,” Stewart told Ken Nigro, “but I never know what’s ahead. You look at the starters and you see it in their eyes. They know what’s ahead, they know when they’re going to pitch and in what town and to what batters. Me? I don’t have anything to look forward to, no plan. They just tell me, ‘Sammy, you might be in there tonight.’” A pitcher who can thrive in those circumstances is indeed invaluable to a manager. “I’d like to have the chance to pitch 250 innings and get 40 starts a year. … I think ’83 is the year.”7

In 1982 Stewart did get 12 starts, mostly in May, but the rest were spot starts, and as the year wore on he became more disappointed that he never had more opportunities to start on a regular basis. He did let it be known, but there wasn’t a lot Weaver felt he could do. Stewart won 10 games (against nine losses), but saw his ERA climb to 4.14, in part because of problems due to bone chips in both knees which occasioned a 21-day disabled-list stint and a very brief two-game rehab stay in Hagerstown. The Orioles finished second, by just one game, to the Brewers for tops in the AL East. Sammy had pitched in the next-to-last game of the season, against the Brewers. Milwaukee had a one-game lead. Scott McGregor had given up three early runs to the Brewers, but Stewart came into a game tied 3-3 and allowed just two hits and no runs in the final 5⅔ innings, while watching his teammates build an 11-3 game and pull into a dead heat for first place with one game to play. Jim Palmer was outpitched by Don Sutton in the final game, turning a 4-1 deficit over to the Orioles bullpen after five-plus innings. The final was Milwaukee 10, Baltimore 2. It was another year watching the postseason from home.

The 1983 season was dominated by a major accomplishment: a return to the World Series. Stewart got just one start, but he closed 21 games for new manager Joe Altobelli and put up a 9-4 record (3.62 ERA). The O’s won the division, six games ahead of the Tigers, and took three out of four games in the ALCS. Stewart pitched a third of an inning in Game One, a 2-1 loss to Chicago and the only loss for Baltimore. He’d been brought on in the bottom of the seventh with runners on second and third, two outs, and catcher Carlton Fisk at the plate. He struck out Fisk, keeping it a one-run game. Touched in the eighth for a single and a walk, he was then replaced by Tippy Martinez. He entered the game in the sixth inning of Game Three with his team leading 6-1, and pitched one-hit ball over the final four innings as the Orioles took an insurmountable 3-0 lead in the ALCS.

It was the Orioles over the Phillies in five during the World Series, and Stewart pitched five innings of relief, appearing in Games One, Three, and Four. He faced 18 batters and struck out six, allowing two hits and walking two, and held Philadelphia scoreless throughout, ultimately leaving baseball with an earned-run average of 0.00 in six postseason games. At the plate, he had two more at-bats, striking out once and grounding into a double play. His career batting average was all zeroes as well. But no one cared. The Orioles had won the World Series. Rick Dempsey was selected as Series MVP, but Sammy Stewart was the runner-up. 8 It was Dempsey who had called Stewart “the unsung hero of the staff” even two years earlier.9

Mentioning Dempsey triggers a story from the August 22, 1980, game in Oakland. Baltimore led 3-2 heading into the bottom of the ninth. Pinch-hitter Mike Davis tripled to lead off, and Stewart starting shouting at Dempsey regarding the pitch he’d called. “I wouldn’t mind if he got upset inside,” Dempsey said, “but not prancing around on the mound. I told him the run hadn’t scored so let’s battle our way out of it.” Two strikeouts and a groundout, and the battery embraced and walked off the field.10

It might also have been a year (1983) when Stewart overcame a problem with alcoholism. He was arrested on July 8, only driving 40 miles per hour but driving erratically. He was given a small fine and sentenced to 18 months’ probation. Both Earl Weaver (who’d been arrested three times himself for drunken driving) and Joe Altobelli said they would work with him, and apparently they did. July 8 – “that’s the date of my last scotch and water. I’m glad it happened. … I needed help,” Stewart said in October.11 The episode was not the last problem he would have with substance abuse.

Things fell apart for the team in 1984. The Orioles finished 19 games out of first place. Stewart led the staff again, this time appearing in 60 games and became a defined closer, finishing 39 games and with a career-high 13 saves. He was 7-4, with an improved 3.29 ERA. It wasn’t much better in 1985, and Stewart finished almost as many games (36), while pitching quite a few more innings and seeing significant increases in the number of hits, walks, and more than double the number of home runs allowed. His ERA at 3.61 was still superior to the team’s 4.38. On December 17, 1985, Stewart was traded to the Boston Red Sox for infielder Jackie Gutiérrez. Boston was anxious to build a better bullpen.

Other than the experience of leaving the only organization for which he’d ever played, in one way the year may have turned out better: the Orioles sank to last place, and the Red Sox went to the World Series. Stewart, however, missed a big chunk in the middle of the season, after a May 31 arm injury, not pitching at all from June 8 to July 27. He pitched 63⅔ innings, by far his lowest total, and, though he was 4-1, it was despite a 4.38 ERA. Worse, he’d lost the confidence of manager John McNamara. “If they let me pitch, we would’ve won that Series,” he told the Globe’s Stan Grossfeld. McNamara may not have cottoned to some of his clowning in the clubhouse, but Grossfeld says Stewart told him that he wound up in the doghouse due to a time the team bus pulled out and left him behind at Fenway Park. Stewart said he’d been visiting his son Colin in the hospital, but had arrived at the ballpark on time, thrown his bag on the bus, and was parking his car when the bus pulled out without waiting. He got into bitter arguments with traveling secretary Jack Rogers and with McNamara, and may have burned a bridge or two. During the World Series, Stewart said of McNamara, “He lay down on me and it cost us the World Series. I hated to see Al Nipper come out of the bullpen when I’ve never been scored on in the postseason and my arm was feeling good.”12

On November 12 Stewart was granted free agency – in other words, the Red Sox let him go.

Opening Day 1987 came and went, and Sammy Stewart still didn’t have a job. On June 4 he was signed by the Cleveland Indians, shuffled to Buffalo for six innings of work in six appearances (0-1, with a poor 9.26 ERA) but still brought up to the big leagues for what proved to be his swan song: Beginning on July 2, he appeared in 25 games, throwing 27 innings. His first appearance helped the Indians win a game; he came in during the top of the ninth of a 1-1 tie in Chicago with one out and a man on. He retired five White Sox in a row, carrying the game through the 10th. Cleveland ultimately won it in the 11th.

Called upon again in the top of the ninth the next day, Stewart was hammered mercilessly by the same White Sox. This time he’d been asked to hold a 9-8 lead, but he gave up two hits and three walks, threw a wild pitch, and saw all five runs score. By season’s end he had whittled that ERA down to 3.32 in mid-September, then seen it climb back to a final 5.67. He wasn’t asked back, released on October 29, at which point he’d reached the end of the string in Organized Baseball. He retired the following year. His final totals were 59-48, 3.59, with 45 saves.

In his life after baseball, Stewart struggled. His son, Colin, died in 1991. His daughter, Alicia, had a double lung transplant. Baltimore Sun sportswriter Dan Connolly explained more: “Most Orioles fans know the dark side of Stewart’s story, too. He became addicted to crack cocaine following his playing career, and was charged 46 times with more than 60 offenses over a decade-plus, primarily stemming from his drug use. At one point he was homeless and penniless.” He’d thrown it all away. Connolly wrote, “In 2006, he began serving a sentence of at least six years for a felony drug charge and is currently incarcerated at the Buncombe Correctional Center in Asheville, N.C.”13

In October 2006 Stan Grossfeld wrote a lengthy profile of Stewart in the Boston Globe, after visiting him at North Carolina’s Piedmont Correctional Institution. Stewart wrote, “‘There’s a lot of times I wished I would have died because I was pathetic,’ he says matter of factly. ‘I guess I started digging a hole for myself and it got so bad I got homeless, moneyless, friendless. I just started covering myself up instead of climbing out of the hole.’” He told of sleeping under bridges, of shooting up and getting shot at. He untruthfully told people his daughter had died, so he could get some sympathy and ask for a little money to help out. Unsurprisingly, his wife, Peggy, and Stewart separated.

This author tried several times to correspond with Stewart at the facility he’d moved to after Piedmont, the Buncombe Correctional Center in Asheville – but never heard back. However, following the August 2011 suicide of Mike Flanagan, Stewart did send an open letter to fans in care of Dan Connolly in which he said, in part, “These last five years have definitely altered my reality; prison is not the place to be. I’m glad I have learned humility, and I work hard to stay teachable. We all must.

“Thank you guys for all the good times and wonderful memories. I am a richer man for them. Hopefully, when I get out of prison on the 10th of January, 2013, there will be a 30th anniversary reunion for the ’83 champs of this world; I will be there with clear and focused – and potentially dampening – eyes.”14

Stewart was released from prison in January 2013 and settled in Hendersonville, North Carolina, hoping to rebuild a happier life.15

He was found dead on March 2, 2018 at a residence in Hendersonville, North Carolina.

This article appeared in “The 1986 Boston Red Sox: There Was More Than Game Six” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Leslie Heaphy.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited within this biography, the author consulted the subject’s player file and questionnaire at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the online SABR Encyclopedia, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Thanks to Sammy Stewart and his friend Cherie Linquist for reading over the biography for accuracy in September 2013.

Notes

1 See Bill Nowlin and Lyle Spatz, “Choosing Among Winners of the 1981 AL ERA Title,” Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2011.

2 Ibid. Righetti did not qualify for the American League title, however.

3 Albany Times-Union, June 2, 1981. The Palmer quote comes from the Boston Globe of October 25, 2006. Revering felt he’d been disrespected. A week later, on June 2, he hit an 11th-inning homer off Stewart to win a game.

4 The Sporting News, April 3, 1982.

5 Albany Times-Union, June 2, 1981.

6 Albany Times-Union, June 2, 1981. Gammons wrote in The Sporting News, March 28, 1981.

7 Boston Globe, October 25, 2006.

8 Boston Globe, October 25, 2006.

9 Albany Times-Union, June 2, 1981.

10 Unattributed September 13, 1980, clipping in Stewart’s Hall of Fame player file.

11 Unattributed October 17, 1983, clipping by Mike McAlary in Stewart’s Hall of Fame player file.

12 Boston Globe, October 25, 2006.

13 Baltimore Sun, October 10, 2011.

14 Baltimore Sun, October 10, 2011.

15 Dean Hensley, Hendersonville Times-News at BlueRidgeNow.com, April 22, 2013.

Full Name

Samuel Lee Stewart

Born

October 28, 1954 at Asheville, NC (USA)

Died

March 2, 2018 at Hendersonville, NC (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.