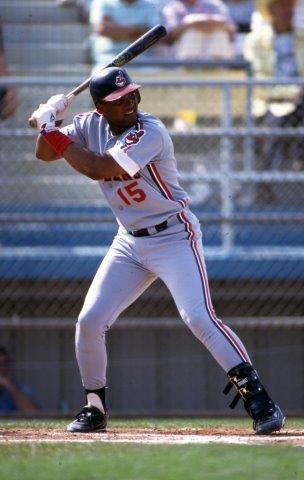

Sandy Alomar Jr.

Jacobs Field in Cleveland was the site for Major League Baseball’s 68th All-Star Game on July 8, 1997. A sold-out crowd of 44,916 turned out for the midsummer classic as it returned to the shores of Lake Erie for the first time since 1981. The host Indians ended the first half of the season on a positive note, sweeping Kansas City in a three-game set. They held a 3½-game lead over second-place Chicago at the break.

Jacobs Field in Cleveland was the site for Major League Baseball’s 68th All-Star Game on July 8, 1997. A sold-out crowd of 44,916 turned out for the midsummer classic as it returned to the shores of Lake Erie for the first time since 1981. The host Indians ended the first half of the season on a positive note, sweeping Kansas City in a three-game set. They held a 3½-game lead over second-place Chicago at the break.

One of the reasons for the Tribe’s success was the unlikely power coming from the bat of Sandy Alomar Jr. The veteran backstop started the season in fine fashion, as he slugged a home run in five consecutive games from April 4-8. His 11 home runs at the break matched his season total of the season before and were just three short of his career-high 14 homers in 1994. “I’m in a zone,” said Alomar. “Everything looks like a beach ball.”1

But it was more than the long ball that Alomar was contributing to the team’s fortunes. He owned the second-longest hitting streak in franchise history, 30 games (from May 25 through July 6). The streak, in which Alomar batted .429, was second only to Nap Lajoie’s 31-game streak in 1906. “It’s been a remarkable run for him,” said the Twins’ Paul Molitor. “To be able to have the mind-set to call a game (as catcher) and still be able to do that. …”2

For the All-Stars on July 8, pitching was the name of the game. The teams battled to a 1-1 tie through the top of the seventh inning. Each team scored its tally on a home run. Edgar Martinez, who was the first designated hitter elected to the All-Star Game, socked a 2-and-2 offering from Greg Maddux into the left-field plaza in the bottom of the second frame. In the top of the seventh, Braves catcher Javy Lopez led off with a solo shot off the Royals’ Jose Rosado.

Jim Thome led off the bottom of the seventh inning by grounding out. Bernie Williams walked and with two outs took second base on a wild pitch by the Giants’ Shawn Estes. Alomar, who had replaced Ivan Rodriguez in the bottom of the sixth inning, stepped to the plate. “When Sandy went to the plate, Paul O’Neill turned to me and said, ‘If all things were fair, Sandy would hit a homer and win the ballgame,’” said Indians manager Mike Hargrove, one of manager Joe Torre’s coaches for the game.3 Sandy sent a 2-and-2 pitch from Estes on a line into the left-field bleachers. “I felt like I was flying,” said Alomar. “I’ve never run the bases so fast on a home run.”4

The 3-1 AL advantage stood up, as the junior circuit snapped a three-game losing streak. The NL was held to three hits. Alomar became the first Indian to homer in the All-Star Game since Rocky Colavito in 1959. Alomar was voted the game’s MVP, the first Indian to be so honored and the first player ever to win the award in his home ballpark. “This is a dream I don’t want to wake up from,” said Alomar. “You probably only get one chance to play an All-Star Game in your home stadium.”5

“It was another of those storybook things,” said Torre. “I had one last fall [the 1996 World Series], and now this. I was happy for Sandy to win it in his own park.”6

Santos (Velazquez) Alomar was born on June 18, 1966, in Salinas, Puerto Rico. He was the middle child (older sister Sandia, younger brother Roberto) born to Santos and Maria Alomar. Sandy Sr. suited up for six different teams over a 15-year career in the major leagues. He had a career batting average of .245. He was mainly a second baseman, although he also saw time at shortstop. After his playing days, Alomar coached 15 years on the big-league level. In addition to his time in the major leagues, Sandy Sr. also managed the Puerto Rican National Team.

The elder Alomar did not push his sons into baseball. “The only influence is from them seeing me play,” he said.7 The life of a ballplayer means a lot of travel and time away from the family. Sandy Sr. credited his wife, Maria, with raising their three children, saying, “She deserves more credit than me. I was a ballplayer and couldn’t be around that much. She stayed home and raised those kids. That’s why they’re the kind of people they are.”8

Roberto Alomar took to baseball right away. He had the natural ability to play the game and at age 7 he made Sandy’s little league team for 9-to-12-year-olds. But for Sandy, he had other interests to keep him busy. “Sandy left the game at age 12 and got into dirt-bike riding and karate,” said his father. “He was doing dangerous things, more or less. He said the only way he could find excitement in baseball was to become a catcher.”9

Young Sandy took to catching and was signed as an amateur free agent on October 21, 1983, by the San Diego Padres. After graduating from Luis Munoz Rivera High School in Salinas, Alomar began his journey to the major leagues. It was a long climb indeed. At first, the going was rough for the young catcher, who hit a combined .221 through his first three years in the minor leagues. But like most talented players, Alomar put in the work and by 1987 he blossomed into a coveted prospect in the Padres chain. It became a family affair of sorts, as Roberto joined his older brother on multiple minor-league squads. Sandy Sr. joined San Diego manager Steve Boros’ coaching staff in 1986.

In 1988 Alomar was named co-Minor League Player of the Year by The Sporting News (with Gary Sheffield of Denver). Alomar, who was the catcher for the Las Vegas Stars of the Pacific Coast League, batted .297 and had career highs in home runs (16) and RBIs (71). “I didn’t expect to hit like that,” said Alomar. “As the season started, I struggled a little bit, but then I started swinging harder and pulling the ball more and hitting more home runs.”10

It was reported that 22 of the other 25 major-league clubs were interested in acquiring Alomar. The Padres already had their catcher of the future in Benito Santiago. The time looked right to possibly trade their star prospect and get plenty in return. While Santiago was the National League Rookie of the Year in 1987, Roberto was promoted to the Padres in 1988 and became their starting second baseman. Sandy was frustrated, feeling there was nothing more he could do on the minor-league level. Rumors persisted that he would be traded, or that Santiago might be moved. One rumor had Alomar headed to Atlanta for All-Star Dale Murphy. “Every organization in the league would love to have a Sandy Alomar,” said Atlanta general manager Bobby Cox.11

But no deal was ever made and Alomar returned to Las Vegas in 1989. He started the season poorly, batting .242 up to June 5, and then he became a man possessed, batting .351 the rest of the way. For the season, Alomar batted .306, with 13 home runs and 101 RBIs. He showed value behind the plate as well, fielding his position at a .984 clip, and throwing out 34 percent of would-be basestealers (25 of 74). He was once again honored by The Sporting News and Baseball America as the Minor League Player of the Year. “It means a lot to me,” said Alomar of the award. “The way I felt, I was so frustrated. I figured there was no way I’d win it again.”12

When the Cleveland Indians front office offered slugging outfielder Joe Carter a multiyear deal at the end of the 1989 season, Carter said, “No thanks.” He could be a free agent at the end of the 1990 season, and was looking forward to leaving Cleveland, and getting a fresh start – not to mention snagging a boatload of cash. Alomar, who was getting frustrated with his situation in San Diego, was just hoping for a chance to play in the big leagues. After all, he had accomplished all he could in the minors, and it really did not matter to him whose uniform he was wearing. On December 6, 1989, at the annual winter meetings, Cleveland GM Hank Peters and San Diego GM Jack McKeon hammered out a deal that sent Carter to the Padres and Alomar, infielder Carlos Baerga, and outfielder Chris James to Cleveland.

Alomar was penciled in as the starting catcher as soon as the ink was dry on the trade. He did not disappoint. Cleveland manager John McNamara praised his young backstop in all facets of his game. “To me, he’s very, very impressive at blocking balls,” said McNamara. “He does it even when there’s no need, when nobody is on base. Sandy’s been taught well. He’s absorbed the teaching, put it to good use.

“Sandy is hitting for a better average than I expected at this stage of his career. He’s adjusted very well to major-league pitching. I never had any doubt about his catching, but you just never know about his hitting.”13

McNamara was not the only person to notice the outstanding play of his prized rookie. All of baseball took notice when Alomar was voted the starting catcher for the American League in the All-Star Game. He was the first rookie catcher ever to start in an All-Star Game. The game would be extra-special, as Roberto, then with San Diego, was also named an All-Star and Sandy Sr. would also join his sons as a coach for the NL at Wrigley Field for the midsummer classic.

Sandy’s season was capped off with his being the unanimous choice for the AL Rookie of the Year. “This award means more to me than the All-Star Game,” said Alomar. “You have a lot of chances to be in the All-Star Game, but you’ve only got one chance to win this award. I was supposed to be Rookie of the Year, and that made it tough. I was traded for Joe Carter, and that made it tough. But the manager and the rest of the guys on the team really helped me.”14 Alomar was the fourth Indian to win the award. He was also awarded a Gold Glove for excellence in fielding his position. He was the first Indian to be so recognized since Rick Manning in 1976.

Alomar was instantly a fan favorite among Indians fans. However, the injuries began to pile up beginning in 1991, his second season. Though Alomar was selected to start the All-Star Game in both 1991 and 1992, he was dealing with myriad setbacks that included back surgery, injuries to his right rotator cuff, his right hip flexor, his right knee (two, caused by sliding), and the webbing between the fingers on his right hand (also twice). The 132 games Alomar played in his rookie year were the most of his career.

The Indians moved across downtown to their new ballpark, Jacobs Field, for the 1994 season. Alomar, despite missing time on the disabled list with the torn webbing on his right hand, was putting together a wonderful season, batting .288 with 14 home runs and 43 RBIs, when the players’ strike on August 11 led to the remainder of the season being canceled.

Perhaps because Alomar suffered so many injuries, Cleveland signed Tony Peña before the 1994 season. For the next three seasons, the veteran provided solid leadership and was a reliable substitute for Alomar. It was a great free-agent signing for the Indians, as Alomar was recuperating from knee surgery and did not return to the active roster until June 29, 1995. Still, he batted .300 in 54 starts at catcher that season. The Indians, who sported one of the most potent lineups in baseball, moved Alomar to the bottom of their lineup. “I think Sandy can still hit 10 to 15 homers this year,” said manager Mike Hargrove. “He has that kind of power. The thing that is really impressive is the way he’s accepted hitting ninth. The number 9 hitter is usually the weakest hitter in the lineup, but that’s not the case with this team.”15

The Indians returned to the postseason for the first time in 41 years, winning their division by 30 games. They marched through the American League playoffs before losing to Atlanta in the World Series.

The Indians won the AL Central from 1995 to 1999. In 1997 they advanced to the World Series again, only to lose to Florida in seven games. Alomar’s power surge in 1997 continued in the postseason, as he hit two home runs in the ALDS, one in the ALCS, and two in the World Series.

The Indians won the AL Central from 1995 to 1999. In 1997 they advanced to the World Series again, only to lose to Florida in seven games. Alomar’s power surge in 1997 continued in the postseason, as he hit two home runs in the ALDS, one in the ALCS, and two in the World Series.

In 1999 Alomar was reunited with brother Roberto, who signed a free-agent contract with Cleveland. Together with Omar Vizquel, they formed one of the better middle-infield defenses in the big leagues. But Sandy missed most of the season after surgery on his left knee (he started 35 games), and in 2000 he split time with Einar Diaz at catcher. That season he batted .289 and drove in 42 runs.

But the end of an era was near as Alomar and the Indians were unable to negotiate a contract after the 2000 season. Alomar, ever the classy player, took the “life goes on” route and signed with the Chicago White Sox. He split time with Mark Johnson at catcher.

But the White Sox were just as interested in Alomar’s ability to teach their young receivers and work with their green pitching staff. He was traded to Colorado in 2002, but returned to the South Side for the 2003 and 2004 seasons. “I got kind of teary-eyed when he got traded,” said pitcher Mark Buerhle. “I’m still learning (from him). I’m out there thinking, ‘I’m going to throw this pitch,’ and he puts something else down. I’m not going to shake him off because he’s been around the league a long time.”16

The White Sox made it clear that they wanted Alomar to work with Miguel Olivo, a catching prospect for whom the front office had high hopes. In 2003 Sandy was reunited again with Roberto, who by this time in his career was serving as a utility player for Chicago.

Alomar spent the remaining years as a backup catcher with Texas (2005), the Los Angeles Dodgers and the White Sox (2006), and the New York Mets (2007). He retired with a .273 batting average in a 20-year career. He hit 112 home runs and 249 doubles, and drove in 588 runs. He threw out just over 30 percent of baserunners, and fielded at a .991 clip at catcher for his career.

Alomar stayed with the Mets as a catching instructor in 2008 and 2009. Manny Acta was hired to replace Eric Wedge as Cleveland’s manager in 2010. Acta offered Alomar a job as his first-base coach. “I jumped at it,” said Alomar. “For me, it was coming home. No place in baseball means as much to me as Cleveland.”17

Acta was fired near the end of the 2012 season. Alomar was named interim manager, and looked to be the favorite until Terry Francona’s name was thrown into the mix of candidates. “I knew they’d hire him if he wanted the job,” said Alomar. “I don’t blame them. I understand. He’s won two World Series. He’s a heck of a guy.”18

As of 2019, Alomar was Francona’s first-base coach. Francona, who played for the Indians in 1988, was a teammate of Alomar’s in winter ball with Ponce in the Puerto Rico League. When the Indians acquired Alomar in 1989, Francona gushed at the young man’s ability. “He’s the best catcher I’ve ever played with,” said Francona. “He’s better than Gary Carter when Carter was good. Sandy might not drive in 100 runs like Carter did in his prime, but overall he’s a better ballplayer. He’s the best defensive catcher I’ve ever seen. His arm is almost incredible.”19

When Francona insisted that Sandy Alomar be a part of his staff, he knew exactly what he was getting. Even way back when.

Last revised: June 1, 2018

This biography appeared in “Puerto Rico and Baseball: 60 Biographies” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Edwin Fernández. It also appeared in “1995 Cleveland Indians: The Sleeping Giant Awakes” (SABR, 2019), edited by Joseph Wancho.

Photo credit

National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 Bill Livingston, “Sweet Sandy! AL Triumphs on Alomar Blast,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 9, 1997: 1A.

2 Mel Antonen, “Sandy Alomar’s Streak Hits 30,” USA Today, July 7, 1997: 1C.

3 Paul Hoynes, “Sandy Steals the Show; Alomar’s Home Run Lifts AL,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 9, 1997: 1D.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 “Sweet Sandy.”

7 Chuck Johnson, “Alomar Sons Deepen Roots in Baseball,” USA Today, July 13, 1990: 2C.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 “Big League Awards in the Minors,” The Sporting News, December 5, 1988: 46.

11 Barry Bloom, “Alomar Hopes That His ‘First’ Won’t Last,” The Sporting News, December 4, 1989: 52.

12 Ibid.

13 Sheldon Ocker, “Alomar More Than Lives Up to Hype,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1990: 12.

14 Paul Hoynes, “It’s Unanimous! Indians Catcher Alomar Is Rookie of the Year,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 8, 1990: 1F.

15 Paul Hoynes, “Deep Thunder Alomar Homers Twice at Bottom of Order,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 21, 1995: 1D.

16 Nancy Armour (Associated Press), “Sandy Ready to Teach,” Elyria (Ohio) Chronicle-Telegram, March 3, 2003: C4.

17 Terry Pluto, “Playing, Coaching for Tribe ‘Paradise,’ Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 3, 2013: C3.

18 Ibid.

19 “Alomar Draws Praise From Former Mate,” The Sporting News, March 19, 1990: 30.

Full Name

Santos Alomar Velazquez

Born

June 18, 1966 at Salinas, (P.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.