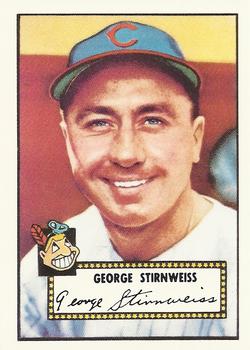

Snuffy Stirnweiss

On the morning of September 15, 1958, Central Railroad of New Jersey commuter train No. 3314 was nearing Bayonne when it ran through several signals and plunged off an open drawbridge into Newark Bay. Forty-eight people lost their lives. One of the victims was George “Snuffy” Stirnweiss, a second baseman who played for the New York Yankees between 1943 and 1950. During his second and third seasons, he earned accolades as one of the top players in the American League. Most notably, he was the 1945 American League batting champion.

On the morning of September 15, 1958, Central Railroad of New Jersey commuter train No. 3314 was nearing Bayonne when it ran through several signals and plunged off an open drawbridge into Newark Bay. Forty-eight people lost their lives. One of the victims was George “Snuffy” Stirnweiss, a second baseman who played for the New York Yankees between 1943 and 1950. During his second and third seasons, he earned accolades as one of the top players in the American League. Most notably, he was the 1945 American League batting champion.

Of the eight Yankees that have won batting titles, Stirnweiss is the least-remembered, the most obscure. Two weeks after his death, Arthur Daley wrote in the New York Times, “Many fans already had forgotten that the stocky little Yankee second baseman of yesteryear had won a hitting crown until that fact was cited in the stories of his tragic death recently in the New Jersey train disaster.”1

George Henry “Snuffy” Stirnweiss was born on October 26, 1918, in New York City. His parents were Sophie (née Daly) and Andrew P. “Andy” Stirnweiss, a city policeman. George also had a younger brother, Andrew P. Stirnweiss, Jr., who was a career U.S. Navy pilot serving in WW II, Korea, and Vietnam.

George starred in baseball, football, and basketball at Fordham Prep in the Bronx. In 1935 he led his team to the New York City Catholic High Schools Athletic Association baseball championship. In the title game, which Fordham won, 5–2, the New York Times reported, “Stirnweiss … was the batter who did the most damage . . . After clouting a long triple into deep right field in the first inning … [he] came through with a home run in the seventh, a prodigious drive to right centre. … In the other two trips to the plate Stirnweiss was passed.”2

It was no different on the gridiron. “Stirnweiss Smashes Through for Touchdown. . .” began the subhead of an October 20, 1935, Times article reporting on a 6–6 tie between Fordham Prep and Brooklyn Prep. It also was noted that “superb punting by Captain Stirnweiss aided the Fordham cause.” In basketball, he helped lead Fordham to the Bronx-Westchester Catholic High Schools Athletic Association basketball crown.

Stirnweiss graduated from Fordham Prep in 1936, and eventually was inducted into the school’s Hall of Honor. At the University of North Carolina, he became the first Tar Heel to captain the football and baseball teams. He was heralded primarily for his gridiron exploits at UNC, where he was a quadruple threat as halfback-quarterback-punter-punt returner. Fordham University’s coach Sleepy Jim Crowley observed, “I regard George Stirnweiss as the most dangerous back we have to face. . . . He is likely to score every time he gets his hands on a punt or a pass.” On another occasion, Crowley remarked, “[Stirnweiss] can kick sixty yards under pressure and he’s a jackrabbit with that ball. In our game, I got the creeps every time we had to punt to him.”3

Stirnweiss was the first-team quarterback on the 1938 Associated Press All-Southern Conference team. He averaged 6.2 yards per carry at North Carolina, and in his senior year was the nation’s sixth best punter. In 1940, he was awarded the Patterson Medal, presented to the Tar Heels’ most outstanding senior athlete.

Stirnweiss’s baseball accomplishments in college did not match his football heroics, but he did hit .390 as a senior, and Paul Krichell, the Yankees’ top scout, was determined to sign him. Upon his graduation in 1940, the five-foot-eight, 175-pounder was drafted in the second round by the National Football League Chicago Cardinals. But Stirnweiss felt that baseball allowed him the best chance for an extended pro career. What’s more, he was an ardent Yankees fan. And so, on the day of his graduation, he signed with his hometown team.

The Yankees assigned Stirnweiss to the Norfolk (Virginia) Tars in the Piedmont League. He appeared in eighty-six games and batted .307, earning him an end-of-the-season promotion to the International League Newark Bears. According to The Sporting News, it was here that Stirnweiss was first dubbed Snuffy. The paper reported that upon arriving in Newark he produced an array of tobacco products. After watching him stuff his mouth with chewing tobacco and light up a stogie, teammate Hank Majeski quipped, “What, no snuff?” “Since then,” the paper noted, “he has been ‘Snuffy the Bear’.”

That fall Stirnweiss remained in Virginia and coached and played for the Norfolk Shamrocks, a pro football team competing in the Dixie League. He spent future off-seasons working as an athletic director at William and Mary College in Williamsburg, Virginia, coaching football and basketball at Connecticut’s Canterbury Prep School, coaching football and baseball at his alma mater, and operating a baseball school in Bartow, Florida.

Stirnweiss spent the 1941 season at Newark, batting an unimpressive .264. He returned to the Bears in 1942, and it was then he really began to flourish, as he honed his skills as a base stealer under the tutelage of new manager Billy Meyer. His .270 batting average was unexceptional, but his speed electrified fans—and he set an International League record with seventy-three stolen bases. Stirnweiss “steals bases like no one else since the days of Ty Cobb,” gushed Michael F. Gaven in The Sporting News. Gaven further described Stirnweiss as “a player and gentleman of the old school” and “just about the best prospect in the minors today.”4

During the 1942 season, Stirnweiss smashed a triple and two singles in the first-ever International League All-Star Game. That summer, he also almost landed in Brooklyn. On August 20, The Sporting News reported that Ed Barrow, the Yankees’ general manager, had been discussing such a trade, but nixed the deal after he began feuding with Dodgers president Larry MacPhail.

Ten days later, the Bears clinched the International League pennant. Between games of a doubleheader, he put on quite a show, first running a 75-yard dash in 8.2 seconds and then circling the bases in 14 seconds. It was while playing for the Bears that Stirnweiss began dating Jayne Powers, an ardent baseball whom he later married.

On March 21, 1943, the New York Times reported, “George Stirnweiss breezed into town, the first infielder on the grounds [of the team’s Asbury Park, New Jersey, training camp]. . . . Interest centered on the arrival of Stirnweiss a day early. . . . He will be something of a novelty if he carries [his] speed with him to the Stadium.” Joe Gordon was entrenched at second base, but Stirnweiss also worked out at shortstop, a position that had been vacated when Phil Rizzuto entered the navy. The rookie impressed manager Joe McCarthy, who declared that he expected Stirnweiss to develop into a top shortstop.

A severe stomach ulcer—some accounts note that he also suffered from an acute case of hay fever—was expected to keep Stirnweiss out of the military. But there was confusion regarding his draft status, as his registration was in the process of being transferred from Norfolk, Virginia, to Connecticut. (Stirnweiss then was residing in Kent, Connecticut.) Then he was inexplicably classified 1-A, and was advised at the end of March that he would be called into the military within a month.

McCarthy nonetheless named Stirnweiss his starting shortstop and lead-off man prior to the team’s initial exhibition game. He held down both positions for the season opener, on April 22, against the Washington Senators. On April 28, Stirnweiss took a train from New York to Hartford, Connecticut to take an Army physical. It was here that he was rejected for military service.

Stirnweiss was relegated to a utility role in his rookie season. He appeared in eighty-three games, mostly at shortstop, with a .219 batting average. But after Joe Gordon entered the Army, Stirnweiss began the 1944 season as the Yankees’ second baseman and lead-off hitter. In the eighth inning of the home opener against Washington, he displayed his speed by beating out an infield hit, stealing second, going to third on a wild pitch, and scoring on a balk. “The art of base stealing may have passed out with the horse-and-buggy age,” wrote John Drebinger in the New York Times. “But, just as the horse has come back in this gas-restricted era, so has the stolen base. Its modern trail blazer is a stockily built athlete named George Stirnweiss, better known as Snuffy.”5

Stirnweiss played in 154 games in 1944 and his .319 batting average was fourth best in the American League. Additionally, he led the league in runs, hits, triples, and stolen bases. His sixteen triples tied teammate Johnny Lindell for the lead, and his 296 total bases were one behind Lindell, the league leader. He was fourth in the league’s Most Valuable Player voting. That September Time magazine described Stirnweiss as “the apple of [Joe] McCarthy’s managerial eye.” In media reports, Stirnweiss was not merely the Yankees second baseman, he had become their star player.

In June 1945, Arthur Daley wrote, “The youngster has improved so amazingly in little more than a season that even as astounding a performer as Joe Gordon may have trouble in winning back his job.”6

Stirnweiss was named to the American League All-Star squad (though no game was played in 1945) and was feted for his accomplishments in a late-September game at Yankee Stadium. On the final day of the season, he was second to Chicago White Sox third baseman Tony Cuccinello in the American League batting race. Stirnweiss was at .306, while Cuccinello was at .308—or, more specifically, .308457. Cuccinello’s number remained frozen, as a rainout ended his season, but Stirnweiss came to bat five times and totaled three hits; two were solid, and he was credited with the third when the official scorer changed his ruling from an error to a hit. Thus, he emerged with an average of .308544—which was rounded off to .309—and the AL batting championship.

It was the lowest figure to win the crown in either league since Cleveland’s Elmer Flick hit exactly .308 in 1905; as of 2011, only Carl Yastrzemski’s .301 has been lower. Additionally, Stirnweiss won the title without ever having led the race during the season. He appeared in 152 games and topped the league in plate appearances (717), at-bats (632), runs (107), hits (195), triples (22), extra-base hits (64), total bases (301), stolen bases (33), and slugging average (.476). He finished third in the MVP race behind pitcher Hal Newhouser and second baseman Eddie Mayo of the pennant-winning Detroit Tigers. That off-season, Stirnweiss won the Sid Mercer Memorial Plaque, given to the player of the year as voted on by the New York chapter of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America.

Nevertheless, Stirnweiss was uncertain of his status when he reported to the Yankees’ training camp in the Panama Canal Zone in 1946. Among the veterans returning from military service were Joe Gordon and Phil Rizzuto, who were expected to be reunited as the team’s double-play combination with Stirnweiss moving to third base. Furthermore, the batting champ would relinquish to Rizzuto his lead-off spot in the batting order.

Stirnweiss also was displeased with the $15,000 contract offered him by the Yankees, which he initially returned unsigned. The Sporting News observed that he was “in a position to ask for a fine contract and is not likely to be sucker enough to weaken.” However, Arthur Daley sardonically quipped, “Free-Advice Department: George Stirnweiss is hereby warned to watch his step. If the holdout Yankee star continues his wage battle with Larry MacPhail [now the top man with the Yankees], the rambunctious redhead probably will sell him to the Chicago Cubs . . . for $100,000 and a couple of used bottle tops.”

By the beginning of March Stirnweiss had signed and reported to the team. Before the season began, Dan Daniel, writing in The Sporting News, described him as “one of the American League’s up-and-coming young stars, whose versatility and high skills would make him a worthy rival for prewar stars returning from the service.”7

But Stirnweiss’s 1946 numbers were way down, and though he earned a spot on the American League All-Star squad, the honor was primarily for past achievements. In July, St. Louis Browns skipper Luke Sewell observed, “How can anyone account for a fine ball player like George Stirnweiss . . . poking along this year at a .240 pace? From all I’ve seen there is absolutely nothing the matter with him. He is the same player who more than once raised hob with my pitchers in the past. But he just isn’t clicking.”

Overall, Stirnweiss appeared in forty-six games at second base and seventy-nine at third. He returned to second full time in 1947 and 1948, after Gordon was traded to Cleveland, but his batting average and stolen base totals were well below his 1945 peak. He did, however, set Major League records in 1948 for the best fielding average (.9930) and the fewest errors (five) at second base, records that stood until 1964 and 1988 respectively.

“He was called a war-time freak,” wrote Charles Dexter in Baseball Digest, “but last summer [1947] as the Bombers regained their peace-time stature, little George worked fielding wonders around second base, clicking off double plays with his partner, Scooter Rizzuto, like a mechanical man.”8

Stirnweiss opened the 1949 season as the starter, but he was spiked in the hand on Opening Day. Jerry Coleman, a rookie whom he had tutored during spring training, replaced him, and won the position. Stirnweiss played in just fifty-one games at second base, mostly as a nonstarter.

That winter Stirnweiss frequently was mentioned in trade rumors. He began the 1950 campaign a Yankee, but was strictly a bench-warmer. At the June 15 deadline, after having appeared in just seven games, Stirnweiss was shipped to the St. Louis Browns in a seven-player deal that brought pitchers Tom Ferrick and Joe Ostrowski to New York. He made it into ninety-three games for the Browns, hitting .218. “There can be no denying the fact that Snuffy had become a Yankee expendable,” wrote Arthur Daley.9 One reason was Coleman’s emergence. Another was that Casey Stengel, the Yankees’ skipper since 1949, “had fiery Billy Martin up his sleeve as the Yankee second baseman of the future.”10

In April 1951 the Browns traded Stirnweiss to the Cleveland Indians. As the deal was announced, St. Louis skipper Zack Taylor noted, “Stirnweiss has slowed considerably, and I’m going with our new boy, Bob Young, at second base.”11 Cleveland manager Al Lopez declared, “Stirnweiss is an experienced man and a great competitor, but I hope nothing happens to [Ray] Boone or any of our other youngsters on the infield. I’d prefer just to have Snuffy around when we need him on account of an injury.”12

Stirnweiss played in fifty games for the Tribe, hitting .216. After appearing in one game for Cleveland in 1952, he was released. In his decade in the majors, he appeared in 1,028 games and compiled a .268 batting average and had 134 stolen bases.

Stirnweiss appeared in three World Series. In 1943 he made it into one game as a pinch-hitter and went hitless. He played in all seven games of the 1947 Series, getting seven hits and eight walks, and making several excellent defensive plays. Most significantly, in Game Four—the one in which Bill Bevens tossed his almost-no-hitter. Brooklyn’s Pee Wee Reese hit a ground ball up the middle in the first inning that appeared to be a hit, but Stirnweiss darted to his left, snagged the ball, and threw Reese out. He appeared in one game of the 1949 Series, without coming to bat.

Following his release by Cleveland, Stirnweiss completed the 1952 season with the American Association Indianapolis Indians. Two years later he signed to manage the Schenectady (New York) Blue Jays, the Philadelphia Phillies’ Eastern League affiliate. On July 16 the Phillies made him a roving batting instructor for several of their lower-level farm teams.

In 1955 Stirnweiss was a manager again, leading the Eastern League Binghamton (New York) Triplets, a Yankees affiliate. After the season, he met with officials of the International League Richmond Virginians. “I’d like to get the [manager’s] job here,” he declared, but he was not offered the slot.13

The responsibilities of providing for his growing family led Stirnweiss to abandon baseball at the professional level. But his desire to impart his knowledge to youngsters made him an ideal choice to run the New York Journal-American sandlot baseball program. He accepted this job in April 1956. That same year, he was hired as a solicitor of new accounts for the Federation Bank and Trust Company. On the morning of June 24, 1957, he collapsed while working at the bank’s Columbus Circle office and was rushed to Manhattan’s Roosevelt Hospital. The nature of his illness remains unclear—according to some reports, he suffered a heart attack—but what is certain is that the episode ended Stirnweiss’ career with the bank.

Upon his death, the media reported that Stirnweiss was employed as a “foreign freight agent” at Caldwell & Co, located at 50 Broad Street in Manhattan. He resided with his family at 140 Maple Street in Red Bank, New Jersey. On September 15, 1958, he was scheduled to represent his company at a luncheon meeting in Manhattan. That morning, he was observed boarding Central Railroad of New Jersey train No. 3314 just before it left the Red Bank station. Had he lived, he would have celebrated his fortieth birthday six weeks later.

A month before the accident, on August 10, Stirnweiss played in the Yankees’ annual Old-Timers Game, which pitted players from the 1946 Boston Red Sox against the 1947 Bronx Bombers. The New York Times reported that “the nifty fielding of [Phil] Rizzuto, Stirnweiss and [Bobby] Doerr drew whoops and hollers from the fascinated fans.”14

Stirnweiss’ funeral was held on September 19 at Red Bank’s St. James Roman Catholic Church. Among those attending were present and former Yankees Rizzuto, Coleman, Joe Collins, and Frank Shea. Stirnweiss was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery in Middletown, New Jersey. At his death, he was the father of six children—two boys (George, Jr. and Edward) and four girls (Susan, Barbara, Cathy, and Mary Ellen)—ranging in age from seventeen months to fifteen years.

Back in August 1956, when the Yankees involuntarily retired Phil Rizzuto as an active player, the Scooter was irate. Stirnweiss advised him to “cool off” and “take a few days’ vacation with Cora and the kids.” “It was great advice,” Rizzuto recalled in 1994, “because when I came back I was offered a broadcasting job. If I had popped off, I would have made people mad and I’d never have gotten it.”15 It was no surprise, then, that Rizzuto occasionally uttered “George Stirnweiss” instead of “George Steinbrenner” during Yankees broadcasts.

Sources

Graham, Frank. The New York Yankees: An Informal History. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1943.

Spatz, Lyle, editor. The SABR Baseball List & Record Book. New York: Scribner, 2007.

Thorn, John, and Pete Palmer, Michael Gershman, and David Pietrusza. Total Baseball, Sixth Edition. New York: Total Sports, 1999.

Dexter, Charles, “Bronx Express: Snuffy Stirnweiss.” Baseball Digest, January 1948.

“Sport: Pennant Parade.” Time, September 11, 1944.

Berkow, Ira. “Too Small to Play, Right Size for Hall.” New York Times, July 31, 1994.

Brady, James. “Brady’s Bunch.” Advertising Age, March 28,1988.

Brands, Edgar G. “Jobs Open—4 of Them—on Brownies’ Infield” Sporting News, February 15, 1950.

Brennan, John. “Sustained Drive for Touchdown Gives Brooklyn Prep Draw With Fordham Prep.” New York Times, October 20, 1935.

Daley, Arthur. “Sports of the Times: List of Distinction.” New York Times, September 29, 1958.

——. “Sports of the Times: Local Boy Makes Good.” New York Times, June 2, 1945.

——. “Sports of the Times: Please Omit Flowers.” New York Times, March 31, 1944.

——. ”Sports of the Times: The Big Trade.” New York Times, June 21, 1950.

Daley, Arthur J. “On College Gridirons.” New York Times, November 16, 1939.

——. “Trick Play Helps Fordham Beat North Carolina, 14-0.” New York Times, October 31, 1937.

Daniel, Dan. “Champion Yankees to Stand or Fall on Legs of Their Vets.” Sporting News, February 15, 1950.

——. “Ed Barrow One Up On Larry In Feud.” Sporting News, August 20, 1942.

——. “High Cost of Living Hikes Salary Ideas of Yankees.” Sporting News, February 15, 1945.

——. “No Razzberry by Yankees on Asbury Return.” Sporting News, October 28, 1943.

——. “Snuffy, Fourth in Scribes’ Poll, No. 1 in Yank Lineup.” Sporting News, November 30, 1944.

——. “Snuffy’s Winning Bat Drive No. 1 Individual Feat.” Sporting News, November 29, 1945.

——. “Yank Tradition Upheld by Etten, Stirnweiss.” Sporting News, September 27, 1945.

——. “Yankees’ Lineup Looks Formidable, But Draft Calls Make It Vulnerable.” Sporting News, March 29, 1945.

——. “Yanks Color Calls Open Race to All.” Sporting News, March 23, 1944.

Danzig, Allison. “Veteran N.Y.U. Array Hopes to Put North Carolina Jinx to Rout on Saturday.” New York Times, October 12, 1938.

Dawson, James P. “Bauer Helps Sain Beat Indians, 5-3.” New York Times, May 15, 1952.

——. “Bonham Shuts Out Red Sox By 5 To 0.” New York Times, April 29, 1943.

——.”Cronin Of Red Sox Chats With Weiss.” New York Times, January 17, 1950.

——. “Garbark’s Single Caps Rally as Yankees Beat Dodgers in Eleventh.” New York Times, April 3, 1944.

——. “Rally In The 7th.” New York Times, April 23, 1944.

——. “Stirnweiss Choice Of Yanks’ Manager As Second Baseman.” New York Times, March 19, 1944.

——. “Stirnweiss Named Lead-Off Man in Yanks’ Batting Order.” New York Times, April 1, 1943.

——. “Stirnweiss’ Triple Enables Yankees To Halt Phils, 5-4.” New York Times, April 2, 1944.

——. “Yankees Retain Title to Etten; Phillies to Get 2 Other Players.” New York Times, March 26, 1943.

——. “Yankees Start Pennant Defense at Stadium by Beating Senators in Ninth.” New York Times, April 23, 1943.

——. “Yankees Triumph Over Red Sox, 12-2.” New York Times, October 1, 1945.

——. “Yanks Welcome Trio Of Rookies.” New York Times, March 21, 1943.

Dean, Clarence. “40 Feared Dead As Train Dives Off Open Newark Bay Bridge; Sunken Cars Trap Commuters.” New York Times, September 16, 1958.

Drebinger, John. “Rizzuto Named Player of Year by Writers; Giants Buy Hughson.” New York Times, December 16, 1949.

——. “Schultz In Service On Capital Review.” New York Times, March 8, 1945.

——. “Sports of the Times: The Man Who Never Walks.” New York Times, August 4, 1944.

——. “Yanks Release Keller and Weigh Two Offers for Newark Franchise.” New York Times, December 7, 1949.

——. “Yanks’ Stirnweiss Voted 1945 Award in Writers’ Poll.” New York Times, January 20, 1946.

——. “Yanks Always Well Fortified Behind Plate.” New York Times, February, 21, 1959.

Flynn, Art. “Hal Edges Staff-Mate Paul Trout.” Sporting News, November 30, 1944.

Gaven, Michael F. “Stirnweiss, Newarks’ Nimble-Limbed Keystoner.” Sporting News, August 20, 1942.

Goldberg, Hy. “Bears Hitting In True Embryo Yankee Style.” Sporting News, March 27, 1941.

Kieran, John. “Sports of the Times: Heard in the Huddle.” New York Times, November 15, 1938.

Madden, Bill. “Generally Speaking, Boss Barrage Motivates Tino. Daily News (New York), October 19, 1998.

Murphy, Ken. “Sports Mill: Thanksgiving Day.” Fayetteville (North Carolina) Observer, November 29, 1939.

Rokeach, Morrey. “Stirnweiss New Director of J-A Sandlot Activity.” Sporting News, April 11, 1956.

Sills, JoAnne. “A day Bayonne can’t forget.” Star-Ledger (Newark), September 14, 2008.

Tuckner, Howard M. “Sox of ’46 Top ’47 Yankees In Not-So-Old-Timers’ Contest.” New York Times, August 10, 1958.

Verducci, Tom. “Value Judgment.” Sporting News, September 30, 2002.

Williams, Joe. “Gordon, Stirnweiss Are Question Marks In Yankees’ Lineup.” Toledo Blade, February 20, 1946.

Young, Charley. “Stirnweiss Fired, Krausse Named Schenectady Pilot.” Sporting News, July 28, 1954.

“Bears Break Even To Clinch Pennant.” New York Times, August 31, 1942.

“Biographical sketches of Dead and Missing Passengers in Bayonne Wreck.” New York Times, September 16, 1958.

“City Title Is Won By Fordham Prep.” New York Times, June 16, 1935.

“Devine Gives Triple-A Tips to New Richmond Owners.” Sporting News, November 30, 1955.

“Fordham Prep Victor.” New York Times, February 2, 1936.

“Former Orphan Takes The Name Stirnweiss.” Daily Register (Red Bank, New Jersey), October 7, 1968.

“International Loop Announces All-Stars.” New York Times, July 2, 1942.

“MacPhail Plans Players’ Bonus From Last Six Games of Yankees.” New York Times, September 22, 1945.

“M’Burney Routed By Fordham Prep.” New York Times, November 2, 1935.

“North Carolina Wins On Passes.” New York Times, October 23, 1938.

“Rejoins Yankees Today.” New York Times, April 30, 1943.

“Snuffy Fills In For Barillari.” Sporting News, August 4, 1954.

“Snuffy Serves Notice He’s After Regular Tribe Birth.” Sporting News, April 18, 1951.

“South Tops North in International.” New York Times, July 9, 1942.

“Stirnweiss and Combs Are Traded to Cleveland for Marsh and $35,000.” Sporting News, April 11, 1951.

“Stirnweiss Coaching Aide.” New York Times, December 6, 1945.

“Stirnweiss Exam Put Off.” New York Times, March 30, 1943.

“Stirnweiss, Ex-A.L. Hitting King, Killed in Rail Tragedy.” Sporting News, September 24, 1958.

“Stirnweiss Gets Pilot Job.” New York Times, January 19, 1954.

“Stirnweiss Is Buried.” New York Times, September 20, 1958.

“Stirnweiss Is Stricken.” New York Times, June 25, 1957.

“Tar Heel Gridmen Among Best.” Fayetteville (North Carolina) Observer, November 1, 1939.

“Yanks Buy 9 Players.” New York Times, September 27, 1942.

“Yanks Get Ferrick In 8-Player Deal.” New York Times, June 16, 1950.

Find a Grave: http://www.findagrave.com

Fordham Preparatory School: http://www.fordhamprep.org

The Hardball Times: http://www.hardballtimes.com

Notes

1. Daley, Arthur, “Sports of the Times: List of Distinction.” New York Times, September 29, 1958.

2. “City Title Is Won By Fordham Prep.” New York Times, June 16, 1935.

3. Kieran, John. “Sports of the Times: Heard in the Huddle.” New York Times, November 15, 1938.

4. Gaven, Michael F. “Stirnweiss, Newarks’ Nimble-Limbed Keystoner.” Sporting News, August 20, 1942.

5. Drebinger, John, “Sports of the Times: The Man Who Never Walks.” New York Times, August 4, 1944.

6. Daley, Arthur, “Sports of the Times: Local Boy Makes Good.” New York Times, June 2, 1945.

7. Daniel, Dan, “Yankees’ Lineup Looks Formidable, But Draft Calls Make It Vulnerable.” Sporting News, March 29, 1945.

8. Dexter, Charles, “Bronx Express: Snuffy Stirnweiss.” Baseball Digest, January 1948.

9. Arthur, Daley, Sports of the Times: The Big Trade.” New York Times, June 21, 1950.

10. Arthur, Daley, Sports of the Times: The Big Trade.” New York Times, June 21, 1950.

11. “Snuffy Serves Notice He’s After Regular Tribe Birth.” Sporting News, April 18, 1951.

12. “Snuffy Serves Notice He’s After Regular Tribe Birth.” Sporting News, April 18, 1951.

13. Devine Gives Triple-A Tips to New Richmond Owners.” Sporting News, November 30, 1955.

14. Tuckner, Howard M. “Sox of ’46 Top ’47 Yankees In Not-So-Old-Timers’ Contest.” New York Times, August 10, 1958.

15. Berkow, Ira. “Too Small to Play, Right Size for Hall.” New York Times, July 31, 1994.

Full Name

George Henry Stirnweiss

Born

October 26, 1918 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

September 15, 1958 at Newark Bay, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.