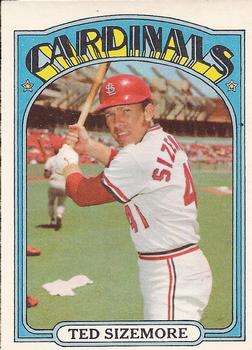

Ted Sizemore

Throughout his 12-year major-league career, Ted Sizemore was known for his versatility and competitiveness, as well as for his love of baseball. When he was playing youth sports, some skeptics told him he was too short to be a major leaguer (sources would later claim he was either 5-feet-9”1 or 5-feet-10”; but in high school, he was often said to be about 5-feet-6).2 Sizemore was determined to prove them wrong, and he refused to give up his dream. That did not surprise those who knew him: Bob Scheffing, a former Detroit Tigers manager who first saw him play high school ball and followed his college career, recalled that the young man volunteered to play any position — catcher, shortstop, second base, outfielder — whatever a team needed him to do. “But that’s Sizemore for you. He’d do anything to play.”3

Throughout his 12-year major-league career, Ted Sizemore was known for his versatility and competitiveness, as well as for his love of baseball. When he was playing youth sports, some skeptics told him he was too short to be a major leaguer (sources would later claim he was either 5-feet-9”1 or 5-feet-10”; but in high school, he was often said to be about 5-feet-6).2 Sizemore was determined to prove them wrong, and he refused to give up his dream. That did not surprise those who knew him: Bob Scheffing, a former Detroit Tigers manager who first saw him play high school ball and followed his college career, recalled that the young man volunteered to play any position — catcher, shortstop, second base, outfielder — whatever a team needed him to do. “But that’s Sizemore for you. He’d do anything to play.”3

Signed by the Los Angeles Dodgers, he became the 1969 National League Rookie of the Year, and during a career that included time with the Dodgers, St. Louis Cardinals, Philadelphia Phillies, Chicago Cubs, and Boston Red Sox, Sizemore proved to be a consistent contact hitter, someone who rarely struck out and knew how to put the ball in play. After finishing his major-league baseball career with a lifetime .262 average, he spent 22 years working for Rawlings Sporting Goods, where he rose to Senior Vice President, and also handled media relations.4

Ted Crawford Sizemore was born in Gadsden, Alabama, on April 15, 1945, and his birth name was “Ted,” not Theodore.5 When he was about 2 years old, his family relocated to Detroit, where he grew up. He was one of four children of Crawford Sizemore, a foreman at the Chrysler plant in Detroit,6 and his wife Thelma Pauline, better known as “Polly” (née Langston). Ted loved sports from the time he was a kid, especially baseball, basketball, and football. At Detroit’s Pershing High School, he was able to play all three. He was the catcher on the school’s baseball team for three years, and he also played some sandlot ball in the Free Press Amateur League.7

In a few years, people would mainly think of him as a baseball player, but in high school, it was his play in other sports that earned him acclaim. As a guard, he was co-captain and the most consistent scorer of the Pershing Doughboys basketball team.8 One Detroit reporter described him as “small but speedy, and an especially dangerous shooter from long range.”9 In addition, he quarterbacked the football team.10 (Some online sources that say he played fullback are incorrect, according to Sizemore.)11 One thing that was especially helpful to his high school athletic success was good coaching: he regarded football coach Mike Haddad and basketball coach Will Robinson as mentors, and he also received encouragement from his father, who volunteered at the local Highland Park Boys Club, where Sizemore played baseball and basketball.12

He thought about trying out for the Detroit Tigers,13 but his mother and father were insistent that he go to college rather than immediately playing professional sports. After graduating from Pershing High School in 1962, he received a baseball scholarship from the University of Michigan, where he also played intramural football and basketball.14 As a freshman he alternated between playing the outfield and catching, then became the regular catcher and, as a sophomore, the team captain.15 16 Meanwhile, he was pursuing a degree in education, but his love for baseball and his desire to play professionally became increasingly important. In the summer of 1965, he and several of his Michigan teammates went to South Dakota to participate in the semipro Basin League, where they could get some additional playing time. As a member of the Pierre Cowboys, Sizemore batted .274.17 In addition, he recalls, everyone on the team was expected to help around the ballpark; when he wasn’t playing, he swept the stands.18

In early 1966, a promising University of Southern California pitcher named Tom Seaver was selected by the Atlanta Braves in the secondary phase of the January draft, and by late February, he had signed a contract. However, the MLB Commissioner, William Eckert, stepped in and voided it because USC had already begun its 1966 spring schedule. (The rules stated that no major league club could sign a collegiate player once his season had begun.)19 About that same time, a Braves scout offered Sizemore a contract. Eckert voided that one, too.20

Fortunately, things worked out for Sizemore. Los Angeles Dodgers scout Guy Wellman had seen him play college ball and believed he had major league potential. In early June 1966, Sizemore was drafted by the Dodgers in the 15th round. He left Michigan without graduating, and went off to Washington state to join the Dodgers’ Single-A farm team, the Tri-City Atoms, managed by former Dodgers great Duke Snider.

He immediately proved Guy Wellman right, batting .330, leading the team to a pennant and winning the league’s Most Valuable Player award.21 In the offseason, Sizemore returned to the University of Michigan and completed a Bachelor of Science in Education in December 1966, making it possible for him to be a teacher when he was not playing minor league ball. This was a sensible decision, since by now, he was married and had a family to support. He and his wife Gloria (née Barchi) would have two children, a son and a daughter, before divorcing in 1976.

In 1967 he was moved up to the Double-A Albuquerque Dodgers of the Texas League, where he was reunited Duke Snider, who told the press he was looking forward to working with several of the players he had managed in Single A, Sizemore among them.22 In addition to batting .295 that year with 61 RBIs, Sizemore led the league in sacrifice flies.23 His accomplishments in Double A earned him a promotion to the Triple-A Spokane Indians of the Pacific Coast League in 1968. Sportswriters noted that he was “highly regarded” by the Dodgers organization,24 and once again, he did not disappoint. Despite spending five weeks on the disabled list with a broken hand,25 he still had a productive year at the plate, leading the Indians with a .314 average, and becoming known for getting timely hits. Because of his injury, he was moved back to the outfield, where he played for the rest of the season.

But even after his injury healed, it turned out that his days as a catcher were about to end. The Dodgers organization already had numerous young catchers, but what they lacked was infielders. That winter, Sizemore was sent to the Arizona Instructional League to learn how to play second base. Fortunately, he had an outstanding teacher in Monty Basgall, a former major leaguer who was then a Dodgers scout. Basgall had a reputation for being able to develop young players; he had taught Julian Javier to play second base.26 Now he was asked to do the same for Sizemore. As Ted recalled, Basgall knew what he was doing. “He was wonderful at teaching infielders. He really drilled me, but he also encouraged me.”27

In 1969, Sizemore was invited to spring training with the Dodgers at Vero Beach, Florida, and he did an acceptable job at second base. But because Dodgers shortstop Billy Grabarkewitz was still recovering from a broken ankle he had sustained in August 1968, Sizemore was asked to move to short. Eager to do whatever was needed, he made the move — and the team. He played 46 games at short before being moved back to second, where he played 118 games. His teammates were impressed with his versatility. Said veteran pitcher Don Drysdale, “Ted Sizemore… has been the biggest surprise. There doesn’t appear to be anything he can’t do.”28

Of course, there were limitations to Sizemore’s ability: he couldn’t singlehandedly lead the Dodgers to the 1969 pennant. The team stayed in contention till mid-September, then lost 10 out of 11 games, finishing in fourth place in the NL West. But Sizemore had a very good year: he hit .271 with 20 doubles, 5 triples, and 46 RBIs. In November the Baseball Writers Association of America made him their overwhelming choice for National League Rookie of the Year.29

The future looked bright for Sizemore in 1970, but injuries slowed him down all year: in spring training, a pulled thigh muscle sidelined him for two weeks, and the nagging injury persisted when the season began. Sizemore tried to play, but he ended up missing several games in April before returning to the lineup. Then, he reinjured the muscle in June, and landed on the disabled list for 21 days.30 And even after he came back, he did not feel 100% healthy till August. He began to hit again and started looking like the same player who had won the Rookie of the Year award a year ago. But in late August, he sprained his left wrist and missed several more games, then in mid-September reinjured his wrist. The team doctor told him to sit out the rest of the season.31 Although he hit .306 in 96 games, it was a disappointing year over all, culminating in the Dodgers trading him, along with catcher Bob Stinson, to St. Louis for slugger Richie Allen.

Sizemore and his wife had just moved into a new home in Los Angeles three days earlier, and the trade was a shock to them both,32 but it soon turned out to be very positive for his career. Before joining the Cardinals, he had minor surgery to remove bone fragments in his previously injured wrist, and after agreeing to a contract, he reported to his new team in late February 1971. His recovery from the surgery took a little longer than expected, but once he got into the lineup, he began to play the way the Cardinals had hoped. At first, he alternated between shortstop and second, but the more he played, it become apparent to Cardinals management that second was Sizemore’s best position, and he began playing there more often.33 He got off to a slow start at the plate, but managed to finish with a .264 average. More important, he avoided more injuries, appearing in 135 games.

One of Sizemore’s goals in 1972 was to become a more consistent hitter, and by mid-season, he seemed to be well on his way. Batting behind leadoff hitter Lou Brock, who frequently got on base and was always a base-stealing threat, Sizemore, who rarely struck out, knew how to protect Brock if he was trying to steal. He was also able to get Brock over to third. Local sportswriters began saying that Sizemore was “perhaps the best No. 2 hitter in the National League.”34 But his fielding was erratic all season, and once again he was injury-prone, only playing 120 games. Still, he finished 1972 with a batting average of .264. In the offseason, he worked for the Pepsi-Cola Company, and frequently gave talks to youth groups and high school students.35

Sizemore was optimistic about 1973, telling reporters he believed he could be a 300 hitter if he could just remain healthy.36 But in late April, a hamstring injury forced him to go on the DL, and he missed three weeks. However, this time, after he recovered, he didn’t miss any more games. And it turned out to be a very good year for him: he played in 142 games, and while he didn’t get to .300, he had a career high .282 batting average with 54 RBIs. And as they had done the previous year, he and Brock provided the Cardinals with a dynamic 1-2 punch.

The same would be true in 1974, when Brock set a record for steals with 118, and whenever he got on base, Sizemore continued to do the little things to help him get into scoring position. As one sportswriter explained, “Sizemore stood far back in the batter’s box, forcing catchers to back up, buying Brock additional fractions. On the jump, Sizemore often swung late or swiped a fake bunt, anything to distract a frantic receiver.”37 But while Sizemore earned praise from his teammates for being so unselfish,38 he continued to be injury-prone, missing much of July with a groin injury, although he did go on to play 130 games. And while at times he got some big hits, his batting average fell to .250, in a year while the Cardinals nearly won the National League’s Eastern Division, finishing second, a game and a half behind the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Sizemore returned to the Cardinals in 1975, but it would turn out to be his final year with the team. His batting average fell to .240. However, he did have one unusual 16-game streak in which he made only one hit — a single — in each game.39 In addition, his defensive play was not as good as in previous seasons; in one game, he made three errors in an inning, becoming one of only 11 major league second basemen to have that dubious distinction.40 When the Cards finished far out of contention, he was among the players local sportswriters expected to be traded.41 They were right. In early March 1976, he was sent back to the Los Angeles Dodgers in a trade for outfielder Willie Crawford. Sizemore had asked to be traded to L.A., where his family still lived, when he learned he would no longer be the Cards’ regular second baseman.42

The Dodgers had always liked Sizemore’s versatility and his scrappy style of play, and they were happy to have him back. He began the year at second base, filling in for the injured Davey Lopes. After Lopes returned, Sizemore sometimes pinch hit, and sometimes he played second base, with Lopes moving to center field. In early August, he was briefly pressed into service as a catcher, a position he hadn’t played since 1968. After regular catcher Steve Yeager was injured, Sizemore stepped in, his first time catching in a major league game. (He admitted it felt strange to be back behind the plate after all that time.)43 But despite being able to step into any role the Dodgers needed, Sizemore hit only.241 in just 84 games. After being told he would once again be a utility player next year, he asked to be traded to a club where he could play more regularly.44 In December 1976, he was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies for catcher Johnny Oates and a player to be named later.

The Phillies gave Sizemore the opportunity he sought, signing him to a four-year contract and making him the regular second baseman. He quickly won over the fans and the local media. One sportswriter who watched him play said his batting average was deceptive: Sizemore was praised for rarely striking out, for being “the best in the business” at hitting behind base stealers,45 and for “[doing] the little things that separate winners from losers.”46 The regular season turned out well for the Phillies: for the second year in a row, they finished first in the National League East, once again compiling a record of 101-61. Sizemore had a good year too: he hit .281 in 152 games, and led National League second basemen in turning double plays with 104.

But the postseason was a different story. For the second year in a row, it ended in disappointment, as the Phillies were defeated by the Dodgers in the playoffs. One especially difficult loss in that 1977 postseason came to be known as “Black Friday,” and a Sizemore error was part of an epic collapse that saw the Phillies blow a 5-3 lead in the ninth inning of Game Three, losing, 6-5, in a game they should have won.47 Years later, when asked about it, Sizemore was philosophical. “As a player, I never dwelled on [the bad days],” he said. “Of course, I’ll always remember the bad games, but you have to let it go.” 48

Sizemore had avoided injuries in 1977, but in late April 1978, he broke his left hand and missed seven weeks.49 When he returned to the lineup, he struggled with his hitting as well as his fielding, finishing at .219. However, when the Phillies made the playoffs once more, Sizemore came through with some big hits, batting .385. Unfortunately, he was one of the few Phillies hitters who made anything happen, and that lack of timely hitting caused the team to lose the NLCS to the Dodgers yet again.

Hoping to shake things up, the Phillies acquired Pete Rose from Cincinnati in late December, and manager Danny Ozark announced Rose would play first base in 1979. He also announced that Phillies first baseman Richie Hebner would move to third, and Gold Glove third baseman Mike Schmidt would become the second baseman. Sizemore was suddenly the odd man out, and faced with not playing very much, he resigned himself to the idea that he would probably be traded.50 In late February, he was part of a multi-player deal that sent him to the Chicago Cubs.

By now, Sizemore was 34 years old and coming off a bad year, but reporters in Chicago noted his enthusiasm and confidence. He said his hand was all better, and he was ready and eager to play every day. He also said he would do just as good a job as Manny Trillo, the Cubs’ previous second baseman, who had been sent to the Phillies as part of the trade that brought Sizemore to Chicago.51 However, Sizemore’s time in Chicago was short, as a result of an argument he had with Cubs manager Herman Franks in early August, after a game in Montreal. As Sizemore recalls it, the Cubs had just lost their sixth in a row, and it was also the day that New York Yankees catcher Thurman Munson died in a plane crash. Some of the Cubs, including Sizemore, had known him, and everyone was in a bad mood.52 The players wanted to toast Munson at dinner, but the team put a strict limit on how many bottles of wine were allocated to each table. Sizemore was one of three players who called the management “cheap” and made some rude remarks on the team bus. He later tried to apologize, but Franks refused to accept it, telling reporters that Sizemore was “a whiner and a complainer,” and accusing him of having a bad attitude. He wanted Sizemore gone.

On August 17, 1979, the Cubs traded Sizemore to the Boston Red Sox, who were seeking an experienced utility player. In his Red Sox debut against the White Sox, he had three hits and drove in two runs, but within a few days, he had torn a shoulder muscle and missed a week and a half before returning to the lineup. Sizemore appeared in 26 games, playing mostly at second, and finished with a .261 batting average. But once again, he was involved in a controversy with his manager, this time during a bus ride in mid-September after the team had eaten dinner at a Baltimore restaurant. Sizemore and several teammates claimed they were just joking around, but their comments got out of hand and upset both manager Don Zimmer and veteran Carl Yastrzemski. And just like before, Sizemore had to apologize, although he and the others who were involved in the incident all said they felt it had been blown out of proportion. Zimmer disagreed, saying he expected his players to “act like men, and not kids.”53 On the other hand, Sizemore has some positive memories of that season, including being in the lineup on September 12, the day Yastrzemski made his 3,000th hit.54

Sizemore returned to the Red Sox in 1980, but few sportswriters expected him to stick around. He was the subject of numerous trade rumors, and he only played in nine games. On May 27, when he made his final appearance in a Red Sox uniform, he was batting just .217. After a potential trade to St. Louis fell through, the Sox waived him on May 30 to make room for Dave Stapleton, who was called up from Pawtucket.55

As it turned out, that May 27 game was also Sizemore’s last in the major leagues. He tried to work something out with St. Louis, where he and his wife then lived and where he had many friends. He still wanted to play, but he and the Cardinals couldn’t reach a deal, and he received little interest from other teams. “I didn’t want to coach, and I couldn’t see myself as a bench player,” he recalled. It was his wife who encouraged him to retire and seek out new opportunities, and he decided she was right.56

For several years, Sizemore worked in the financial services industry, first for Merrill Lynch, then Dean-Witter, before being hired by Rawlings, a sporting goods company then based in St. Louis, in February 1984. Rawlings was the supplier of much of the equipment used by Major League Baseball; it also sponsored the annual Gold Glove award, given to baseball’s best fielders. In his new position as Vice President of Baseball Development, Sizemore interacted with both amateur and professional teams, as well as their players and coaches. In addition to promoting Rawlings products, he was tasked with promoting baseball as an Olympic sport, which was very timely, given that the 1984 Olympics were taking place in Los Angeles. At that time, baseball was just a demonstration sport, but Sizemore was hopeful that would soon change.57 In 1986, the International Olympic Committee voted to make baseball an official Olympic sport in time for the 1992 games.

His work not only took him all over the United States, but to many foreign countries, where he promoted Rawlings products, and helped baseball to expand internationally. Sizemore was also involved with contract negotiations and player endorsements, and he worked with various athletic governing bodies, including the NCAA and the International Olympic Committee. He was enjoying his new career. “I love [baseball] so much, and I want to see it played around the world,” he said.58

In the summer of 1992, rumors began to circulate that Sizemore was being considered for president of the National League, replacing Bill White, who was about to retire.59 In the end, the job went to business executive and financier Leonard S. Coleman Jr. Sizemore remained with Rawlings; in early 1999, he was promoted to Senior Vice President for Worldwide Baseball Affairs; in addition, he began overseeing media relations for the company.60

Sizemore had always been involved with charitable endeavors, serving as a director of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and working with the Boys Clubs. After a career with Rawlings that lasted more than two decades, he turned his focus to another charity he had long respected: MLB’s Baseball Assistance Team (BAT), which raised funds to help former players and their families if they were in need. An avid golfer, he participated in numerous celebrity tournaments that raised funds for BAT. By 2008, he was serving as the organization’s president, and then continued serving on its board of directors. Working with BAT, said Sizemore, “is one of the things I’m the most proud of, [because of] the number of people we helped.” He noted that the work was always done anonymously: the public did not know, unless players or their widows chose to speak about what BAT had done for them.61

As an alumnus who made good, he has been honored by the University of Michigan since 1982, when the baseball team created the “Ted Sizemore Award,” given annually to its best defensive player.62 And in November 2019, he was selected for induction into the St. Louis Sports Hall of Fame. Looking back on his career, Sizemore is proud of what he accomplished, both as a major leaguer and afterwards. “I’ve been blessed to live a special life,” he says, “knowing and playing with so many great players.”

Last revised: November 23, 2020

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

The author interviewed Ted Sizemore by telephone twice, on September 15 and 18, 2020. The author also made use of statistics from baseball-reference.com, U.S. census data from Ancestry.com, and the online archives of the University of Michigan’s school newspaper, the Michigan Daily.

Notes

1 Jack Saylor, “Who’s the Top Rookie in NL? Detroit’s Own Ted Sizemore,” Detroit Free Press, November 29, 1969: 1B, 2B.

2 Ken Clover, “Pershing Rifles Past Kimball,” Detroit Free Press, March 18, 1962: D3.

3 Quoted in Bob Broeg, “Bob Scheffing: Dollars, Sense, and Sentiment,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 30, 1972: 2C.

4 “People in Business,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 1, 1999: BP 19.

5 Author interview with Ted Sizemore, conducted by telephone, September 15, 2020. Hereafter, Sizemore interviews.

6 “He Teaches Boys About Guns,” Detroit Times, September 15, 1960: NW6.

7 “Free Press Nines Run Hot and Cold,” Detroit Free Press, July 14, 1963: D3.

8 Hal Schram, “Quick Start is Doughboys’ Only Chance,” Detroit Free Press, November 27, 1962: D3.

9 Ken Clover, “Pershing Rifles Past Kimball,” Detroit Free Press, March 18, 1962: D3.

10 Hal Schram, “Ted is Pershing’s Cage Quarterback,” Detroit Free Press, January 7, 1963: 2D.

11 Sizemore interviews

12 “He Teaches Boys About Guns,” Detroit Times, September 15, 1960: NW6.

13 Sizemore interviews

14 Jack Saylor, “Ted Sizemore: From Rookie of the Year to Year of Woe,” Detroit Free Press, July 19, 1970: 6D.

15 “Wolverine Nine Pick Sizemore,” Detroit Free Press, May 26, 1964: 1D.

16 Jim LaSovage, “M Nine Try Again to Open Season,” Michigan Daily (Ann Arbor, Michigan), April 11, 1964: 6.

17 Rick Feferman, “Summer Leagues Help Diamondmen Progress,” Michigan Daily, August 31, 1965: 6.

18 Sizemore interviews

19 “Braves Lose Tom Seaver,” Palm Beach (Florida) Post, March 6, 1966: D1.

20 Sizemore interviews

21 Morris Moorawnick, “Sizemore Just a Stone’s Throw from Los Angeles,” Detroit Free Press, December 28, 1967: 9.

22 Frank Maestas, “Snider Looking Forward to Season in Duke City,” Albuquerque Journal, February 24, 1967: C2.

23 Chuck Whitlock, “Here’s How,” El Paso Times, October 1, 1967: 2D.

24 “Bruce Turns Longest Stint,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, April 5, 1968: 20.

25 Mike Lynch, “Indians Crush Oklahoma City 12-2, Pad Winning Streak to 10 Games,” Spokane Spokesman-Review, July 16, 1968: 12.

26 George Lederer, “Arizona League: Baseball School in Private,” Long Beach (California) Independent, November 19, 1968: C2.

27 Sizemore interviews

28 “Drysdale Feels Rookies Can Go All the Way,” Monrovia (California) Daily News-Post, May 14, 1969: 19.

29 Jack Hand, “Dodgers’ Sizemore is NL’s Top Rookie,” Sacramento Bee, November 28, 1969: E1, E3.

30 “Sizemore Joins Disabled List,” Sacramento Bee, June 13, 1970: 10.

31 Gordon Verrell, “Dodgers in a Pinch, Call Verrell,” Long BeachIndependent, September 16, 1970: C6.

32 Gordon Verrell, “Bye-Bye Teddy– Hello Richie!” Long BeachIndependent, October 6, 1970: C1.

33 Bob Broeg, Redbirds’ Improvement Was a Pleasant Surprise,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 1, 1971: 2C.

34 Neal Russo, “Reggie Devours Giants Hitters,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 8, 1972: 1B.

35 Neal Russo, “Sizemore Seeks Rerun of ’70,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 24, 1973: 4C.

36 Neal Russo.

37 Dan O’Neill, “40 years Ago, Lou Brock Stole a Record and Our Hearts,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 10, 2014, B1.

38 Rich Folkers was among the teammates who said Sizemore never got the credit he deserved. Quoted in Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: HarperCollins, 2000), 521-522.

39 Jason Wolf, “Winning Streak Comes to End at Five Games,” Courier Post (Cherry Hill, New Jersey), June 22, 2014: 4.

40 Doug Grow, “Sizemore: 3 For the Book,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 18, 1975, 1C

41 Dick Kaegel, “Cards Want Shortstop Help, But Won’t Rush Templeton,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 30, 1975: 2C.

42 “Cardinals Send Sizemore to the Dodgers for Crawford,” Jefferson City (Missouri) Post Tribune, March 3, 1976: 9.

43 “Dodgers’ Baker Does In Houston,” Beaumont (Texas) Journal, August 3, 1976: 1B.

44 Ross Newhan, “Dodgers Obtain Oates; Sizemore Sent to Phillies,” Los Angeles Times, December 21, 1976: Part III, 1,5.

45 Bruce Keidan, “You Can Bet the Farm on It: Second Base Belongs to Sizemore,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 24, 1977: 3C.

46 Bruce Keidan, “Sizemore Steals One from Bucs,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 3, 1977: 1D.

47 Frank Fitzpatrick, “In Losers’ Derby, Phils are the Champs,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 26, 2003: D2.

48 Sizemore interviews

49 Frank Dolson, “Ginny Ozark Packs Punch,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 3, 1978: 3B.

50 Jayson Stark and Gordon Forbes, “Trade Me, Sizemore Tells Phils,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 31, 1979: 1D.

51 Dave Nightingale, “Sizemore New Cub Cheerleader,” Chicago Tribune, March 6, 1979: Section 4, 1.

52 Sizemore interviews

53 Larry Whiteside, “Sizemore Riles Zimmer,” Boston Globe, September 18, 1979: 45.

54 Sizemore interview. September 15, 2020.

55 Whiteside, “Stapleton Gets the Call,” Boston Globe, May 31, 1980: 26.

56 Sizemore interviews

57 Rich Wiedis, “Sizemore Now Sizing Up Olympic Baseball Talent,” Michigan Daily, April 5, 1984: 7.

58 “Where Are They Now? Ted Sizemore,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch; August 29, 2003: C8.

59 Vahe Gregorian, “Sizemore a Candidate for NL Presidency,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 18, 1992: 4B.

60 “Morning Briefing: Rawlings Promotes Two,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 20, 1999: C2.

61 Sizemore interviews

62 Rich Adler, Baseball at the University of Michigan, (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2004): 94.

Full Name

Theodore Crawford Sizemore

Born

April 15, 1945 at Gadsden, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.