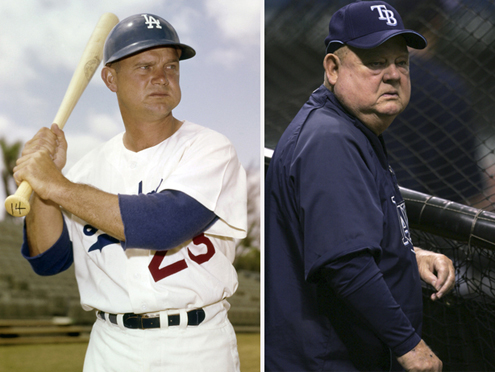

Don Zimmer

You won’t find the definition of “baseball lifer” in the American Heritage Dictionary, but if you did, Don Zimmer’s picture would be a suitable choice to accompany it. Over a period of 60 years, Zimmer claimed to have never collected a paycheck anywhere other than baseball, except once from Social Security.

You won’t find the definition of “baseball lifer” in the American Heritage Dictionary, but if you did, Don Zimmer’s picture would be a suitable choice to accompany it. Over a period of 60 years, Zimmer claimed to have never collected a paycheck anywhere other than baseball, except once from Social Security.

“I never dreamed I’d be in baseball so long that they’d invent jobs to keep me in the game,” Zimmer said in his 2004 memoir. “Maybe that’s not exactly right, but I will say this, before I got a call from Butch Hobson asking if I’d like to serve as his bench coach in 1992, I never heard that term.”1

He was also given several nicknames over the years, including Popeye (because his arms reminded people of the comic-strip character), Zip, and Zim.

Donald William Zimmer was born in Cincinnati on January 17, 1931, to Harold Zimmer, who owned a wholesale fruit and vegetable company, and his wife, Lorraine, who oversaw things at home. His younger brother, Harold Jr. (Hal), played in the minor leagues from 1951 through 1953.

By the time he entered Western Hills High School, Don had become a two-sport athlete, playing football and baseball. He was named the quarterback for an all-Ohio team, and was the star shortstop for the baseball team. Baseball was his real passion. At various times the Western Hills team featured future major leaguers Ed Brinkman, Art Mahaffey, Russ Nixon, Pete Rose, Herman Wehmeier, and Clyde Vollmer, as well as Jim Frey, a major-league manager and general manager.

In 1947 Zimmer’s American Legion team won the national American Legion championship in the finals in Los Angeles. He and his teammates met Babe Ruth and everyone on the team got a ball autographed by Ruth. (Don literally tore the cover off his ball by playing with it.)

The hometown Cincinnati Reds and the Brooklyn Dodgers showed interest in Zimmer. At first Don had his heart set on playing for the Reds, and his father assured the Cincinnati brass that his son planned to sign with them. But the Dodgers’ Branch Rickey, alerted by Cliff Alexander, a bird-dog scout who coached at rival Woodward High School, held a private tryout for Zimmer with Hall of Famer George Sisler, a Dodgers scout. Zimmer hit three or four balls out of the park, and. Rickey offered him $2,500 to sign. The Reds said they could offer only $2,000 but would start Zimmer in Class B ball. Zimmer did not give a hometown discount; he took the Dodgers’ offer.

Zimmer began with the Cambridge Dodgers of the Class D Eastern Shore League in 1949. The next year he played for Hornell of the Class D PONY League, where he batted .315, led the league with 146 runs scored, and stole home 10 times. That season put him on the fast track for the majors. Zimmer moved up to Elmira of the Class A Eastern League in 1951. On August 16 he married his high-school sweetheart, Carol Jean Bauerle, before a game in Elmira.

Zimmer played in 1952 for Mobile of the Double-A American Association.

The Dodgers moved him up to Triple-A St. Paul in 1953. Batting .300 with 23 home runs and 63 RBIs in 81 games, Zimmer was hit on the side of the head by a pitch thrown by Columbus pitcher Jim Kirk in a game at Columbus on July 7. Zimmer’s skull was fractured and he was unconscious for 10 days. As well as Zimmer could remember, it was the first game of a twilight doubleheader. There were trees behind center field, which made it tough for the batter to pick up the ball.2 Because blood clots were forming on his brain, he was given spinal taps every two or three days. Eventually three holes were drilled into the right side of his head. It has been popular to say that Zimmer had a plate in his head, but that is inaccurate; three titanium buttons were inserted in his skull to act like bottle corks. After the procedure, Zimmer’s weight dropped to 124 pounds from his previous 170.

Zimmer recuperated at home in Florida by playing softball before reporting for spring training at Vero Beach in 1954. Since Pee Wee Reese was still the Dodgers’ starting shortstop, Zimmer again began the season at St. Paul. If there were any lingering effects from his beaning, he did not show them. In 73 games he batted .291 with 17 home runs, and when Reese was injured, the Dodgers brought Zimmer up. He made his major-league debut on July 2 at Connie Mack Stadium in Philadelphia, against a tough lefty, Curt Simmons. He hit a triple in his first at-bat.

When Pee Wee recovered, the Dodgers gave Zimmer the choice of returning to St. Paul or remaining in Brooklyn. He chose to stay with the Dodgers. But by the end of the season Zimmer had played in only 24 games, batting.182.

The following season, 1955, was magical for Zimmer, and Dodgers fans. Zimmer had a strong spring training camp and earned the right to be Pee Wee Reese’s backup. And the Dodgers won the pennant. Manager Walt Alston wanted to get Zimmer’s bat into the lineup, and asked him if he could play second base. Though Zimmer had never played second, he assured his manager that he could. His little white lie paid off because he became Brooklyn’s top utility man, playing at both short and second. His hitting gained him playing time, and though he batted just .239, he hit 15 homers and had 50 RBIs in 88 games.

In the World Series, against the New York Yankees, Zimmer started the first two games at second base. He had a hit in each game, but Alston decided to sit him down in Game Three against Bob Turley. The skipper wanted to get left-handed batter Sandy Amoros in the lineup. Alston’s strategy did not sit well with the brash young Zimmer, who let the press know his feelings. Alston did not appreciate his comments and he scolded Zimmer: “This is terrible! We’re winning a World Series and you’re popping off and thinking about yourself?”3 Zimmer did not appear in Games Four and Five, either, but did get into Games Six and Seven as the Dodgers won the world championship.

Zimmer was used sparingly as Reese’s backup in 1956. In a rare start on June 23, his season was ended by a fastball high and inside from Hal Jeffcoat that broke his cheekbone. He downplayed the incident by saying: “If that’s all that Jeffcoat has on the ball, he better quit.”4 Surgery was needed to put the indented bone back in place.5

Zimmer returned for the 1957 season, but remained in a utility role, playing third base, shortstop, and second base. In 84 games he batted just .219. Zimmer thought his days in Brooklyn were numbered. “They’ll trade me, sure,” he told a sportwriter. “They’re not going to want me on this club.”6 Alston thought that Zimmer’s versatility made him useful, but Zimmer insisted that the manager did not like him.

Zimmer was correct: His days in Brooklyn were numbered. In 1958, the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles (and the New York Giants moved to San Francisco). There were several contested infield positions. Charlie Neal moved to second base, Reese, who was in his final year, moved to third. This left Bob Lillis and Zimmer to compete for shortstop.7 Zimmer won the job and responded with his finest season at the plate as a Dodger, batting .262 with 17 homers and 60 runs batted in.

However, Zimmer didn’t last long as the starter. In 1959 he shared the shortstop position with Maury Wills and his batting average plunged to .169. The Dodgers won the pennant and defeated the Chicago White Sox in six games in the World Series. Zimmer’s only appearance was as a pinch-runner and defensive replacement in Game 5.

Just before the 1960 season started, Zimmer was traded to the Chicago Cubs for Lee Handley, Johnny Goryl, and Ron Perranoski, plus $25,000 in cash. Zimmer was appointed the captain of his new club and raised his batting average to .258. The Cubs finished seventh among eight teams.

In 1961, the year Cubs owner Philip Wrigley unveiled his “College of Coaches,” Zimmer overcame the unsettled atmosphere and batted .252 with 13 homers. Zimmer, who had been vocal in his criticism of the College of Coaches, was left unprotected in the postseason expansion draft, and was selected by the brand-new New York Mets.

Playing for the Mets was a homecoming for Zimmer. The team had a number of former Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants players, along with Casey Stengel, the legendary Yankees manager. At this stage of his career, Zimmer approached spring training as a time to get into shape. He did not feel it necessary to make an impression. Admittedly his stint with the Mets was a disaster: 4-for-52, with one RBI. His tenure with the Mets was little more than a month. In May, he was traded to Cincinnati for Cliff Cook and Bob Miller.

The Reds used Zimmer as a backup third baseman and shortstop. He became an expensive commodity for the team and when the season ended, general manager Bill DeWitt sent him a contract with a 20 percent pay cut for 1963, commenting that the Reds could not afford to have a utility player making $19,000 a year. Then on January 24 Zimmer was traded to the Dodgers for minor leaguer Scott Breeden. Cincinnati replaced him with a younger player named Pete Rose.

Zimmer’s second time in Los Angeles was short. On June 24, five months after his arrival, the Dodgers dealt him to the Washington Senators, with whom he played his last 2½ years as a major leaguer. Gil Hodges, his old Brooklyn Dodgers teammate, was his manager. He hit a home run in his first game, and during his stay with the Senators he added two more positions to his résumé. In 1964 he played a few games in the outfield, and near the end of the season, Hodges wanted to pinch-hit for his catcher, Mike Brumley, and asked Zimmer if he could catch. Zimmer responded honestly: “Well, I caught in fast-pitch softball in Cincinnati when I was a kid, but that was the extent of it, sure!”8 So Zimmer pinch-hit and caught the last four innings of the game. After the season, Hodges suggested he take catching seriously and recommended going to the Instructional League that fall.

Zimmer wound up catching in 33 games behind Brumley and Doug Camilli in his last big-league season, 1965, while filling in at third and second, too. After the season Hodges told Zimmer that Washington was dropping him from the 40-man roster to make room for a younger player, but that the door was open to him to compete at spring training. Zimmer’s pride did not allow him to consider the offer. A couple of weeks later, his old friend Al Campanis called him with an opportunity to play in Japan.

The Toei Flyers offered Zimmer $30,000, which was $9,000 more than he was making as a major leaguer. Zimmer hit seven home runs the first two weeks. Then he broke his toe. He played through the injury but tore up his shoulder trying to make the throw from shortstop. That was it. His Far East career ended with a .182 average and 9 home runs in 87 games.

Zimmer was out of baseball until Dodgers executive Buzzie Bavasi came to his rescue. He offered Zimmer a chance to instruct at spring training. At the same time the Reds offered him the manager’s job at Double-A Knoxville. The salary was $8,000, well under what Zimmer was accustomed to. He was hesitant at first, then realized that he had no job. The Reds promised to increase his salary to $12,000 the following season. Zimmer started out as the player manager in Knoxville, then was promoted to manager of Triple-A Buffalo, where future Hall of Famer Johnny Bench was his catcher. Zimmer hit his last professional home run while at Buffalor.

Zimmer went to Puerto Rico after the season to work on his managerial skills. His team, the San Juan Senadores, was filled with major-league talent that included Tony Taylor, Pat Dobson, Rick Wise, and Roberto Clemente (who played only once a week). The team clinched a playoff berth. Zimmer clashed with Ramón Hernández, one of his pitchers. Management sided with Hernández, a Puerto Rican, and fired Zimmer after the team clinched a playoff spot.

Zimmer went to Puerto Rico after the season to work on his managerial skills. His team, the San Juan Senadores, was filled with major-league talent that included Tony Taylor, Pat Dobson, Rick Wise, and Roberto Clemente (who played only once a week). The team clinched a playoff berth. Zimmer clashed with Ramón Hernández, one of his pitchers. Management sided with Hernández, a Puerto Rican, and fired Zimmer after the team clinched a playoff spot.

In 1968 Zimmer managed the Reds’ new top affiliate, Indianapolis. The team included several talented players but many of Zimmer’s starters were called up to Cincinnati, and the team finished the season in fifth place with a record of 66-78 and Zimmer lost his job.

Buzzie Bavasi, who had left the Dodgers for the expansion San Diego Padres, came to the rescue. The Padres had only two minor-league teams, one at Elmira and the other in Key West. Zimmer agreed to manage Key West because it was in Florida, where he lived, but it was far from home. Zimmer was paid only $7,500 for the season. Not only had he taken a pay cut but the clubhouse had no air-conditioning, the team’s bus driver had a drinking problem, and the bus was a rattletrap. The Key West Padres team lasted a single season, but still managed to finish in third place with a 66-64 record in the Florida State League.

The Padres promoted Zimmer to Triple-A Salt Lake City in 1970. The club lacked talent except for Fred Kendall and Walt Hriniak, and finished 52½ games behind the PCL South Division leader, Hawaii. Zimmer resigned after the season.

Gene Mauch, who was now managing the Montreal Expos, asked Zimmer to be his third-base coach for 1971, and Zimmer accepted. Before Zimmer worked with the Yankees’ Joe Torre, he felt that Mauch was the best manager for whom he ever coached.

Once again Bavasi called Zimmer during the offseason, to offer him the third-base coaching job with the Padres in 1972. Zimmer took the job, and when the Padres started 4-7, Bavasi fired manager Preston Gomez, and Zimmer became a big-league manager for the first time. Roger Craig, another old Brooklyn teammate, was the pitching coach. The Padres lacked talent, finishing with a record of 58-95 in the strike-shortened season. As it turned out, the 1973 season in San Diego was Zimmer’s toughest ever as a manager. Not only did the club have difficulties on the playing field, finishing at 60-102, owner C. Arnholt Smith was having financial difficulties and began trading players to dump salaries. The fire sale became too much and Zimmer informed Bavasi that he was quitting. San Diego fired Zimmer after the season. Zimmer took a job as the third-base coach for the Boston Red Sox,

Zimmer enjoyed coaching in Boston, especially working with veterans like Carl Yastrzemski, Luis Tiant, Bill Lee, and Rico Petrocelli. The 1974 team was in first place as late as September 2, but faded down the stretch. Its offense became sluggish, which might have been because the older players were becoming worn out. It did not help that Carlton Fisk missed the second half of the year after knee surgery.

Still, the future in Boston showed promise. Two young players, Rick Burleson and Dwight Evans, joined the Red Sox in 1974. Rookie stars Fred Lynn and Jim Rice emerged the following year. The 1975 team led the American League Eastern Division, then swept Oakland in the Championship Series to advance to the World Series against the Reds. The Red Sox lost the dramatic Series in seven games.

Many consider Game Six the best and/or most exciting World Series game ever. It was won by Carlton Fisk’s home run in the bottom of the 12th. But the Red Sox almost won it earlier. They had the bases loaded with nobody out in the ninth. Fred Lynn lofted a fly ball to shallow left field and Denny Doyle was thrown out at the plate trying to score from third. Doyle later said that when Zimmer, the third-base coach, yelled, “No, no, no,” he thought he was saying, “Go, go, go.”

In 1976 the Red Sox fired manager Darrell Johnson and replaced him with Zimmer. He was asked if he wanted to name a new coaching staff but decided to wait until after the season. The Red Sox finished third at 83-79, 15½ games behind the Yankees.

Zimmer guided the 1977 Red Sox to second place with a 97-64 record. Pitching was not the team’s strength, but the team had a potent offense that featured thumpers like Lynn, Rice, Yastrzemski, Fisk, George Scott, and Butch Hobson, all but Lynn hitting 20 home runs.

The Boston front office was also in turmoil. Owner Tom Yawkey had died in 1976. His widow, Jean, was not thrilled with Dick O’Connell, the general manager, and replaced him with Haywood Sullivan. Still, Zimmer decided to come back for 1978. The tale of the 1978 collapse of the Red Sox is well-documented. The Yankees, once 14½ games behind the Red Sox, swept a four-game series in early September and went into first place. The Red Sox surged back into a tie on the last day of the regular season, only to lose to the Yankees in a one-game playoff highlighted by Bucky Dent’s home run. The team’s breakdown can be attributed, at least in part, to a loosely formed group known as the “The Loyal Order of Buffalo Heads.” The founding members were Ferguson Jenkins, who was traded to Texas before the 1978 season, Bill Lee, Rick Wise, Jim Willoughby, and Bernie Carbo. The buffalo was chosen because the group felt it was the dumbest animal on the face of the Earth. The clique felt that this animal was indicative of those who played for Zimmer. Almost daily there were quotes from out of the clubhouse second-guessing their manager and how the Red Sox were going down the drain.

In a 2004 interview, Bill Lee pinpointed the origin of the group. After the next to last game of the 1977 season, a group of Red Sox players went out drinking. The next morning found Bernie Carbo sleeping underneath the trainer’s table, and Ferguson Jenkins asleep in the bullpen. Lee combated his hangover by going on a six-mile run that morning to “get the poison out.” Mike Paxton was the starting pitcher for Boston on the last day, and was roughed up by Baltimore. So Zimmer called the bullpen to get Jenkins ready to come in. Fergie’s teammates in the bullpen could not believe the request and told the bullpen coach to say that Jenkins was not there.

This signified the start of the bad blood, which intensified in the 1978 season. The Buffalo Heads had no respect for Zimmer, whom Lee referred to “The Gerbil.” Zimmer had little control over the group. The Red Sox sold Carbo to Cleveland on June 15, and Lee staged a brief walkout in honor of his friend. When Lee returned, he was banished to the bullpen and rarely used.9

It’s worth remembering, however, that the Red Sox had rebounded strongly to make it into the one-game playoff. They won 12 of 14 games in the homestretch, the last eight in a row.

Even so, the Boston fans were not a forgiving bunch. On Opening Day 1979, Zimmer was booed when he presented the lineup card. Although the Red Sox won 91 games in 1979, that was good enough only for third place. In 1980, they slid to fourth (83-77). Zimmer admitted that one of his biggest regrets was not winning a championship in Boston.

Zimmer was out of a job before the end of the 1980 season. Johnny Pesky managed the final five games. Once again he did not remain unemployed for long. The Texas Rangers and owner Eddie Chiles came knocking. Chiles had built his fortune from scratch, and though he did not know baseball, he felt he could run it like a business. Chiles had a concept of “formalized goal setting” that were recorded on index cards. He wanted each player evaluated. Zimmer’s responsibility was to write the player evaluations, then have the players evaluate themselves. That did not work because Zimmer threw the cards in the garbage.

The 1981 season was disrupted by a players’ strike. The Rangers were 33-22 when the players walked out. They were in second at the time, half a game behind the Oakland A’s. The second half, after the strike ended, had its share of problems: Mickey Rivers and Bump Wills were hurt a lot, and Al Oliver’s and Buddy Bell’s production had dropped off. They finished in second again for the second half, at 57-48 and five games behind the A’s.

The Rangers did not play at the same level in 1982, losing 12 in a row at one point. Eddie Chiles’ patience wore thin during the losing streak. The Texas owner had a reputation for being erratic. At one point he made Zimmer the general manager as well as manager. When Texas had a terrible road trip in New York, Toronto, Boston, and Detroit, losing 10 games, Chiles fired Zimmer. (His replacement was Darrell Johnson whom Zimmer had replaced in Boston.)

Zimmer was not out of work for long. Oakland A’s manager Billy Martin called to offer a job as his third-base coach. Yankees owner George Steinbrenner made the same offer. Zimmer knew “The Boss” from the horse tracks. He took the Yankees’ offer. Clyde King was the Yankees’ manager at the time, but it was rumored that he would be fired and that Martin would come back to New York. Zimmer became the third-base coach for the Yankees, and indeed, Billy returned to the Bronx in 1983. Zimmer left after one season in New York. He said Martin treated him well but that he was uncomfortable with how Martin treated others.

Zimmer was in line to become the third-base coach for the California Angels in 1984, but then his buddy Jim Frey called. Frey was going to be the new manager of the Chicago Cubs and he wanted his childhood friend to be on his staff. The Cubs won the National League East and were up two games to none against San Diego in the NL Championship Series. But they lost the next three in San Diego. Still, Zimmer felt it had been a terrific season – the team had done what no other Cubs team had in 40 years. He was disappointed but not as deeply as in 1978 with Boston.

In 1985 Chicago went from 96-65 to 77-84, mainly because of injuries. Then in 1986 the Cubs started off at 19-27. After a 3-7 road trip, general manager Dallas Green fired both Frey and Zimmer. Gene Michael became the new Cubs manager.

The next day, George Steinbrenner offered Zimmer a job coaching at third base for the Yankees’ latest manager, Lou Piniella. Again Zimmer stayed for just one season with the Yankees. Steinbrenner and Piniella were at constant odds during the entire season. Piniella did not know what his status was in New York. Zimmer decided to leave, and San Francisco Giants manager Roger Craig, his former Brooklyn teammate, called and offered him a coaching job. Zimmer was with the San Francisco Giants for the 1987 season. The Giants won the Western Division with a strong second half but lost to the St. Louis Cardinals in the NLCS.

The Giants offered Zimmer a two-year contract, but he learned that Dallas Green had been fired as the Cubs’ GM and that Jim Frey was taking his place. Frey called to offer Zim the manager’s job, which he took – the Cubs had a lot of young talent.

The Cubs were below .500 in 1988. Before the 1989 season, Frey and Zimmer decided that their number-one priority was a closer. They targeted Mitch “Wild Thing” Williams, and the price was Rafael Palmeiro. Williams saved 36 games in 76 appearances. The 1989 Cubs were known as “The Boys of Zimmer,” a takeoff on Roger Kahn’s book, The Boys of Summer. The Cubs surprised the league, winning the Eastern Division. A 23-year-old Greg Maddux won 19 games and Mark Grace established himself as one of the premier first basemen in the National League. The Cubs featured four All-Stars, Ryne Sandberg, Andre Dawson, Rick Sutcliffe, and Williams. Jerome Walton captured the NL Rookie of the Year award. But the Cubs lost to the Giants, 4 games to 1, in the NLCS.

In 1990 the Cubs fell back to fourth place, with a 77-85 record. After the team started off the 1991 season with an 18-19 record, Zimmer was fired. That ended his career as a major-league manager; he was 885-858 over 13 years.

For only the second time in Zimmer’s professional baseball career, he found himself at home in the summer without a job. He admitted that it was kind of nice spending time with his family and doing things he was never able to do, such as going to the horse track and enjoying his grandchildren – but he was itching to work in baseball again.

General manager Bob Gebhard of the expansion Colorado Rockies called. They had hired Don Baylor as their first manager and wanted Zimmer on the staff. During spring training at Tucson, Zimmer felt odd on a bus ride after a game; his eyes were burning, and he had problems with his vision. The bus went to a hospital where it was determined that he had suffered a ministroke. Doctors told him to give up chewing tobacco. Zimmer returned shortly to spring training.10

Zimmer sensed in 1994 that his relationship with Baylor had begun to sour. It became more evident during spring training in 1995. There was bad blood between Gebhard and third-base coach Ron Hassey. Baylor was getting in the middle of it. Zimmer was friends with Gebhard, and that association caused friction. Baylor was close to Hassey, and so he ostracized Zimmer. The divide became wider as the season went on; Zimmer informed Gebhard on June 6 that he had decided to retire.

Zimmer returned home and really enjoyed himself that summer, but in his heart he was still not ready to retire. For the first time, he did not receive a call from a major-league team. A friend suggested that he sign up for Social Security. Two weeks later he found a check in the mail. About a week passed, but then he received a call from Joe Torre, who had become the Yankees’ manager and needed a bench coach.

Zimmer served in that capacity from 1996 through 2003. When Torre first called, Zimmer figured that he wanted ask him his opinion on a player, but when Torre offered the bench-coach position, he told his wife, “This is really going to work.”11 Zimmer and Torre had a distant respect for each other when they managed against each other in the National League, but the respect deepened when they worked together. Zimmer claimed that in the eight years he spent with Torre, he never really saw Torre get angry – he was the most even-keeled person Zimmer had ever been around. When Leo Durocher said, “Nice guys finish last,” he did not know Joe Torre. Zimmer said the hardest part about leaving the Yankees was leaving Torre. In seven out of the eight years they coached together, the Yankees won their division. They went to six World Series, winning four times.

One incident marred Zimmer’s tenure with the Yankees. Zimmer’s confrontation with Pedro Martínez during Game Three of the 2003 ALCS, in which Martínez threw Zimmer to the ground, is an image that springs to many minds when Zimmer’s name is mentioned. Yet as Derek Jeter later said, Zimmer’s charge after the benches emptied showed that at 72, he remained a very spirited competitor.

Zimmer did not want to leave the Yankees, but he did so because of George Steinbrenner. He admitted that he should have seen it coming. For years he had seen the way Steinbrenner treated others – Zimmer viewed it as childish and thought that Steinbrenner did not enjoy being happy and that “The Boss” was bothered by not getting enough credit for the Yankees’ success. After the 2003 season, Zimmer decided that he had had enough.

Mentally, he felt he was finally ready for life without baseball. But in stepped Vince Naimoli, the original owner of the Tampa Bay Devil Rays. Naimoli wanted to make use of Zimmer’s knowledge of the game; he offered him the job of senior adviser. One of the biggest selling points was how close Tropicana Field was to Zimmer’s home in Treasure Island – just 15 minutes.

All they asked of Zimmer was to come to spring training as a special coach and instructor, in uniform. Then, when the regular season started, he would sit upstairs in the suites during home games.

Zimmer spent the last 10 years of his life working for the Tampa Rays, from 2004 to 2014. On June 4, 2014, Zimmer died at the age of 83 in Dunedin, Florida. He was survived by his wife, Carol Jean; his son, Tommy; his daughter, Donna; and four grandchildren. Tommy was drafted by the St. Louis Cardinals and played in the minor leagues from 1971 to 1979, rising as high as Double-A in the St. Louis and Pittsburgh organizations. He also managed in the minors, and scouted for the San Francisco Giants for several years.12

Co-author Bill Madden, in their book The Zen of Zim, quoted Zimmer as saying, “All I’ve ever been is a simple baseball man, but it’s never ceased to amaze me how so many more accomplished people I’ve met in this life wanted to be one too.”

“What a game, this baseball!”13

Sources

Barber, Red, When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Co., 1982).

Mnookin, Seth, Feeding the Monster: How Money, Smarts, and Nerves Took a Team to the Top (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006).

Zimmer, Don, and Bill Madden, Zim: A Baseball Life (New York: Total Sports Illustrated, 2001).

Zimmer. Don, and Bill Madden, The Zen of Zim: Baseballs, Beanballs, and Bosses (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004).

The Sporting News, September 20, 1955- October 22, 2003.

Los Angeles Times, September 27, 2001.

New York Times, March 7, 2004, and June 4, 2014.

New York Herald Journal, July 29, 1982.

Markusen, Bruce, “Here Comes the Spaceman,” bruce.mlblogs.com, June 19, 2009.

Notes

1 Don Zimmer and Bill Madden, Zim: A Baseball Life, 3.

2 Red Barber, When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball, 182.

3 Zim: A Baseball Life , 9.

4 Zim: A Baseball Life, 20.

5 Zim: A Baseball Life, 35.

6 The Sporting News, October 10, 1957, 24.

7 The Sporting News, March 12, 1958, 11.

8 Zim: A Baseball Life, 65.

9 Bruce Markusen, “Here comes the Spaceman.”

10 Zim: A Baseball Life, 220, 221.

11 Don Zimmer and Bill Madden, The Zen of Zim: Baseballs, Beanballs, and Bosses, 73.

12 Zim: A Baseball Life, 220, 221.

13 The Zen of Zim, 232.

Full Name

Donald William Zimmer

Born

January 17, 1931 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

June 4, 2014 at Dunedin, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.