Tony Fossas

Tony Fossas was past his 30th birthday before he made the big leagues, but he pitched in 567 games for the Rangers, Brewers, Red Sox, Cardinals, Mariners, Cubs, and Yankees from 1988 through 1999.

Tony Fossas was past his 30th birthday before he made the big leagues, but he pitched in 567 games for the Rangers, Brewers, Red Sox, Cardinals, Mariners, Cubs, and Yankees from 1988 through 1999.

In 166 of those games, Fossas faced only one batter.1 He was what was once called a “LOOGY” (a Left-Handed One-Out Guy), in the days before 2020, when a new rule was implemented that required an incoming pitcher to face a minimum of at least three batters or complete the half-inning in which he appeared.

Emilio Antonio Fossas Morejón was born in Havana, Cuba, on September 23, 1957. He was raised in Guanajay, Cuba, about 35 miles southwest of Havana.

His father, also named Emilio, had a good job as a supervisor for sugar trains in Cuba, checking the electrical poles along the routes. He had first begun working for the railroad at age 13, when his own father had died. As the Fidel Castro regime began to tighten its grip, Tony’s father was apparently a bit too outspoken.

Tom Archdeacon of the Dayton Daily News talked with Tony Fossas in 2014 and reported, “The family had shown interest in leaving Cuba and joining relatives who had fled to the United States and that drew the wrath of government authorities.”2 Tony’s uncle, Silvio Fossas, had emigrated to the Boston, Massachusetts, area the year before Tony was born. He agreed to sponsor the family should they be able to get to the U.S. It took a fraught two years before the Cuban authorities granted approval.

Fossas told Archdeacon, “I can remember jeeps with soldiers coming and taking over houses in our neighborhood. And I remember when they came and took my father away. They called us gusanos — worms. They looked at us like traitors just because we wanted freedom. They took my father off to farms to work and I only saw him a few times over the next couple of years.”3 In a February 2022 interview, he added, “For two years, waiting to get the paperwork, my father was taken away to camps, to work in the sugar cane fields. No one in the family knew where he was. Out of six months, he would come home for two days. Go away for six months. Two days. In a total of two years, before we came [to the United States] on May 21, 1968, my mom and my brother and I only saw him for a total of six days.”4

In Cuba, it fell to Tony’s mother Nelida to provide for him and Misael, his younger brother born in 1960. Another brother, John, was born in 1974 after the family settled in Boston.

Tony was 10½ years old when the family finally departed Cuba in 1968. The “freedom flight” they were on landed in Miami. The family continued north and soon settled in the Jamaica Plain section of Boston, where Silvio Fossas lived. Tony’s father found work at the Regis Paper Company in nearby Newton. He worked there for 23 years as a machine operator, making $2.50 an hour to start. He worked a second job at Boston’s John Hancock Building.5 Mother Nelida worked sewing at a clothing factory in Jamaica Plain.

Tony adds, “We all came together on a Pan American flight. Legally. We’re all American citizens now. I have two kids that were born here, and grandkids who were born here.”

Tony didn’t know a word of English when he arrived, but he found himself playing baseball in his neighborhood just as he had in Cuba, and he began to assimilate.6 He played street hockey and basketball, too, but was best at baseball. He played American Legion ball for the team in Brookline and in the Catholic Suburban League, a league so small that it wasn’t covered by the press. He told Boston sportswriter Peter Gammons, “I struck out 26 in a 13-inning game at Newton Catholic, but there wasn’t even a line about it in the Globe or Herald.” Tony attended St. Mary’s High School in Brookline.

Fortuitously, a local Brookline man took notice of Tony’s talent at baseball. That one man – Howie Kaplan – made a huge difference in the 16-year-old’s life. A left-hander himself, Kaplan had reportedly been drafted by the St. Louis Cardinals at age 19 and played in their farm system before the Army sent him overseas during the Korean War.7 He coached Legion ball in Brookline. Tony wanted to express his appreciation. “I was 16 years old. The first day I was there, I threw a bullpen, and he was there. He pulled me aside and said, ‘Son, if you work hard, you’re going to pitch in the big leagues.’ I stood still out of respect, because that’s the way my parents taught me. But I was far from believing the man. That was my dream and that was what I wanted to be – but I just couldn’t see it. But for the next four years he was on me all the time – about preparation, about working out, running, throwing programs, throwing bullpens, being aggressive, never being down, being a good teammate, respecting the elders. He was like a father, a pitching coach…

“I do not have any idea why he took that interest, but there wasn’t a mile that I ran after that that I didn’t dream about having a Red Sox uniform on. That’s all I could think about. He helped me understand that you have to dream it. You have to really want it, and you have to understand that you learn from failure. He was a very instrumental person in my life.”

Tony built up a bit of a local reputation and attracted some interest from area colleges, but not interest that involved scholarship support.

Red Sox scout Tommy McDonald offered Fossas $2,000 to sign with the team he had followed as he grew up, typically attending a Fenway Park game every weekend. After he saw his first game at Fenway, he said, “My heart bled Red Sox. When the lights went on, I was completely in awe. Burleson and Freddie Lynn and Jimmie Rice and Yastrzemski. I told my dad right then that was exactly what I wanted to do when I grew up.”8

“I wanted to sign that contract so bad,” he had said. “But I was 17 years old. My mother wanted me to get an education. She told me that baseball will end someday, but you’ll always have your education. I can still see her with tears in her eyes about it.”9 He said he was torn and didn’t know what to do but prayed inside the house.

“The power of prayer had done wonders for my family,” Fossas continued, “because at 11 that night, I got a call from Jack Butterfield, who’d left the University of Maine for the University of South Florida [in Tampa]. He told me he needed a lefthanded pitcher.” Tony told Butterfield his family was poor, and Butterfield said he knew Tony’s circumstances and that, while he couldn’t provide a scholarship per se, there was a benefactor willing to pay the full four years plus $16,000. That benefactor was none other than George Steinbrenner.10

Fossas got his degree and performed well pitching for the university. The Minnesota Twins selected him in the ninth round of the June 1978 draft, but he wanted to complete his degree (in education, with a minor in Spanish). Thus, he did not sign until the following year, when he was a 12th-round selection of the Texas Rangers in June 1979. Scout Joe W. Lewis, Sr. is credited with the signing.11

Fossas, who stood an even six feet tall and was listed at 195 pounds, was assigned to rookie ball with the Gulf Coast League Rangers. He was 6-3 (3.00 ERA) in 10 starts. He also started two games in the Double-A Texas League for the Tulsa Drillers and was 1-1; one disastrous start left him with a 6.55 ERA.

In 1980, he progressed to the Class-A South Atlantic (Sally) League and was 12-8 (3.15) for the Asheville Tourists. Fossas put in seven full seasons of minor-league ball before getting his first call to the majors. In 1981, he was 5-6 (4.16) for Tulsa. In 1982, he was sent to Iowa and played Single A for the Burlington Rangers in the Midwest League (8-9, 3.08). He also pitched in three games in Villahermosa, Tabasco, in Mexican League ball but lost all three. In 1983 and 1984 he split his time between Tulsa and the Triple-A Oklahoma City 89ers, though most of his time was in Oklahoma in 1984. That’s where he spent all of 1985 (7-6, 4.75).

During the winter of 1984-85, Fossas pitched winter ball in Puerto Rico. He was on the mound when the San Juan Metros became league champions. Fossas told author Thomas Van Hyning, “It gave me an opportunity to be on an island more or less like Cuba in terms of the weather and rabid fans.” He gave credit to manager Mako Oliveras, who used him as a closer and helped prepare him for the majors.12

As a free agent, Fossas signed with the California Angels and pitched in seven 1986 games for the Triple-A Edmonton Trappers, his sum total for the year. From his first year in 1979, until that year, he had never been hurt. In 1986, he was the Opening Day starter in Hawaii and went nine innings, then four days later he threw another eight or nine innings at Tacoma. In the first game at Edmonton, he was due to start again (he hadn’t known that the plan was for him to work five innings and get called up to the majors), but he got hurt in the first inning. He tried to come back in June, but the pain was too great. After fruitlessly consulting several doctors with Edmonton and in California, he traveled to Boston and saw Dr. Arthur Pappas, who immediately diagnosed the problem and provided the surgery. Fossas had an ulnar nerve transplant – a successful one, as witnessed by the decade-plus of pitching that followed.

Throughout his minor-league years, Fossas always mixed starting and relieving. In 1987, he started 15 games and relieved in 25 others, with a year-end record for the Trappers of 6-8 (4.99).

In May 1988, he got his first brief taste of the big leagues. His debut came on May 15, throwing 2 2/3 scoreless innings for the Texas Rangers at Arlington Stadium against the visiting Kansas City Royals. The Royals already had a 5-0 lead when Fossas entered the game with one out in the top of the fourth inning – but with the bases loaded and star hitter George Brett coming up to bat. He threw one pitch, and Brett grounded the ball back to him, initiating a 1-2-3 double play. The Rangers crept back to a 5-4 final. He pitched in three other May games and one on June 1, then went back to Oklahoma City without a decision and a 4.76 ERA. With the 89ers, he relieved in 52 games, starting none, and finished 3-0 (2.84).

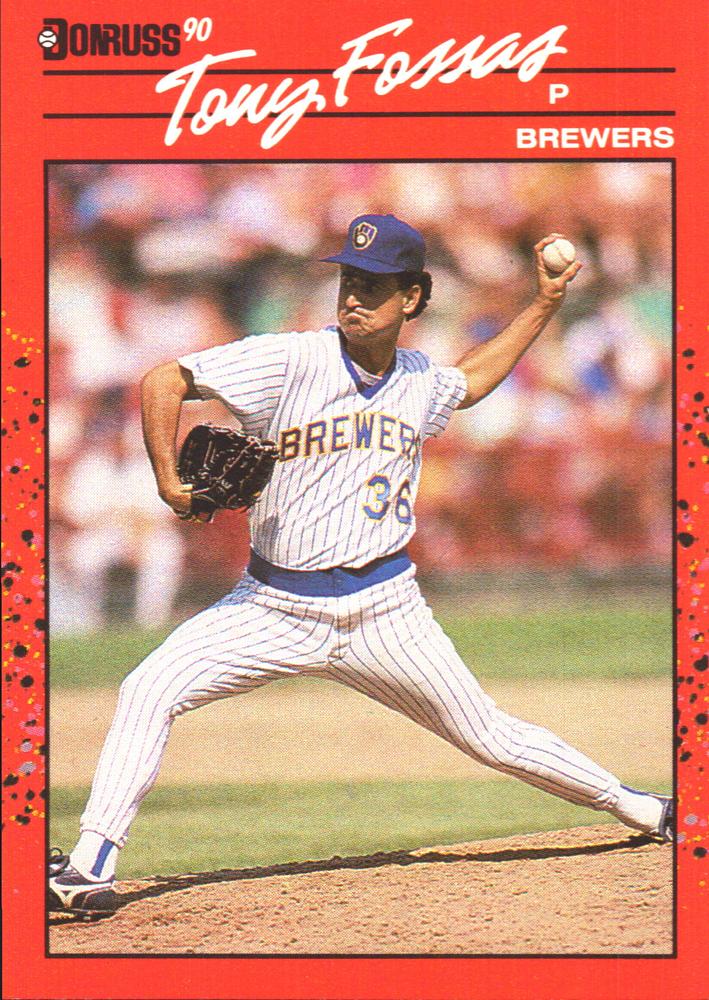

A free agent once more, Fossas signed with the Milwaukee Brewers in January 1989. He started the season with their Triple-A affiliate, the Denver Zephyrs, and was 5-1 (2.04) in 24 appearances when he got the call to join the Brewers; his first game with them was on June 4. His first big-league win came on June 15 at County Stadium against visiting Toronto, pitching the sixth, seventh, and eighth innings as the Brewers came from a 4-3 deficit to take a 5-4 lead. He earned his first save after working 2 2/3 perfect innings against the Red Sox on August 20, in Boston, for a 6-3 Milwaukee win. He relieved in 51 games, throwing 61 innings – in 10 of the appearances he faced just one batter – and had a 3.54 ERA with a 2-2 record.

With the Brewers, Fossas picked up the moniker “The Mechanic,” after Brewers announcer Bob Uecker said he thought Fossas “looked like somebody who would service your car.”13

Fossas opened the 1990 season with Milwaukee, but his year was split between Denver (25 games, 1.51 ERA) and the big club (32 games, 2-3, but with a 6.44 ERA.) After the season, he was released, and signed to a Pawtucket Red Sox contract. He made the big league team in spring training. Finally, he had the opportunity to pitch for the home team in the ballpark he used to frequent in his younger days – Fenway Park.14

The four years he worked for Boston (1991-1994) were his longest stretch with any team. The Red Sox used him extensively. He relieved in 64 games in 1991, 60 in 1992, 71 in 1993, and 44 in 1994 (strike ended the major-league season ended after August 10). The most wins he had in a given year came in 1991, when he was 3-2 with a 3.47 ERA, a total he matched in 1995. Because of how he was used, Fossas rarely had a save; he had seven over the course of his big-league career. He also rarely made the headlines. He contributed, though: his number of appearances was second only to closer Jeff Reardon, and he was credited with 18 holds in 1991.

In 1992, his ERA was 2.43 with a 1-2 record, but in this year and the next, he was at his “LOOGY-est.” Of the 60 games in ’92, in 32 he faced just one batter for manager Butch Hobson. He earned 14 holds. In ’93, with Hobson still at the helm, Fossas faced just one batter on 33 different occasions. Remarkably, from August 26 to September 5, he faced only one batter in eight consecutive appearances. He was 1-1, with 13 holds but a less satisfactory ERA of 5.18.

In 1994, he was without a loss (1-0), but with an 8.31 ERA on May 10, he was sent to Pawtucket – though lefties were hitting only .217 against him. With the PawSox, he worked in 11 games without surrendering a run, earned or otherwise. He rejoined Boston on June 1 and picked up another win that very day. This brought his ERA down to 3.66, but his final outing was disastrous. He was 2-0 with a 4.76 ERA when a work stoppage prematurely ended the season.

When baseball resumed in 1995, Fossas was a St. Louis Cardinal, having signed with them in April.15 Manager Joe Torre was skeptical about using him at first, but over the first 21 games Fossas entered, he didn’t give up a single run. The Cardinals finished fourth in 1995; Fossas was 3-0 with a stellar 1.47 ERA.

The next year, Fossas expressed his confidence in spring training. “I feel comfortable knowing my job is getting the lefthanded hitter out when the game is on the line,” he said. “When I’m on the mound I have ice-cold blood. I don’t care who is in the batter’s box. I feel like I’m going to get them out.”16

Under new manager Tony La Russa, St. Louis finished in first place; Fossas’s 65 relief appearances were second only to the 71 in 1993. Three other Cardinal relievers surpassed 60 appearances as well – T.J. Mathews, Dennis Eckersley, and Rick Honeycutt. Despite a won-lost record of 0-4, his 2.68 ERA was the best on the staff of anyone with a dozen or more appearances. He welcomed the work and added a perspective to being used so much. As he articulated it years later, “I never liked to pitch when I was strong. The more that I pitched, I enjoyed it better. When you are strong, you have a tendency to feel that you can throw harder but when you stay within yourself, you think about changing speeds and you think about location.”17 Fossas relied on a slider and tailing fastball.

Even though he appeared in 202 career games for National League teams, he had only one career at-bat. That was on August 29, 1996, at Busch Stadium in St. Louis. The Marlins had an 8-0 lead at the time. He bunted into an inning-ending 5-6-4 double play. He wasn’t the best of fielders, either, with 11 errors in 107 chances (.897); it was his specialty pitching that made him a sought-after reliever employed in the majors past age 40.

The 1996 season was the only time Fossas pitched in the postseason. The Cardinals swept the Division Series from the Padres but lost a seven-game NLCS to the Atlanta Braves. Fossas didn’t appear at all in the NLDS but pitched in Games One, Four, Five, Six, and Seven of the NLCS. He faced 15 batters over the five games and allowed just one hit – a solo home run by Javy Lopez in a game that was already 10-0 in Atlanta’s favor.

In 1997, St, Louis dropped to fourth place. Fossas worked in a career-high 71 games, matching his 1993 mark. He had a 2-7 record, suffering one stretch (from July 30 through August 13) when he lost four games – all close. He gave up a total of five runs in the four games. His year-end 3.83 ERA was disappointing, but better than the team’s 3.88.

Fossas started the 1998 season with the Seattle Mariners but was released in early June, having worked only 11 1/3 innings with an ERA of 8.74. He had hurt his back while with Seattle but didn’t say anything. The Cubs signed him a little more than a week later, but he worked just four innings in eight games (five times he faced just one batter), giving up four runs in the four frames. The Cubs released him on August 4 and just over two weeks later he was back with the Rangers once more—the team he’d broken in with. He got his first (and only) win as a Ranger in the very last of the 10 games in which he pitched for them, on September 27 in Seattle. He didn’t give up an earned run this time around for Texas (1-0, 0.00).

Fossas was released after the season. In all, he was released eight times. “I never thought of quitting, though,” he said. “Every time it did get tough, I remembered that 8-year-old kid selling duro frios [Cuban popsicles] on the street.”18

In 1999, at age 41, he finally pitched for George Steinbrenner’s Yankees. He’d been particularly excited about joining them. “I was a big fan of the team and Joe Torre was a big fan of me. We had been together in St. Louis. I was excited for the opportunity. I was acting like a little kid, at age 41! I saw George [Steinbrenner, who had funded his college education] and just gave him a big hug and told him, ‘I will always be indebted to you.’ He said, ‘Son, don’t worry about it. It was my pleasure.’”19

Torre was diagnosed with prostate cancer in March that year and missed the early part of the season. He returned on May 18, but Fossas never got to pitch for him in a Yankees game.

The veteran had done his better work elsewhere. He started with Triple-A Columbus but was called up to the majors for bullpen work after Roger Clemens went on the disabled list at the end of April. Fossas appeared in five May games for New York, facing a total of 10 batters but surrendered six base hits and walked one. He was without a decision, designated for assignment three weeks later, showing a 36.00 ERA. All four runs he had given up were in an 8-4 win on May Day, so the only damage done was to his personal stats.

The balance of his season was spent with Columbus, where in 26 appearances he was 1-0 (4.05).20 “Things started going really well again,” he recalled, “Everything was on the upswing. But I got hit by a line drive – my glove hand. It was really bad. The Yankees doctors told me that I’d had a long career and if I wanted to have a good retired life that I should have my hand put in a cast.” He wore a cast for two months. By then, it was time. “I was really done. I was 42 years old and I was done.”

His mentor from Brookline, Howie Kaplan, had been right. Tony Fossas did pitch in the big leagues. In fact, he was one of the most frequently used hurlers of the 1990s (although he averaged just 0.7 innings pitched per outing). “I’m very proud of that number [his 567 total appearances],” Fossas says, “considering that I broke in when I was 30.” Had he done so five years earlier, he might have approached 800 or more games.

A couple of other select numbers underscore Fossas’s effectiveness. Lefties hit just .214 in 702 at-bats against him. And overall, he allowed just 28% of the runners he inherited to score, which is vital for a middle reliever.

Because the Yankees won the World Series in 1999, one might have assumed he got a World Championship ring. He did not. His teammates voted him a partial share. “The players treated me fantastic. I don’t think I deserved the money that they sent me but I was very happy, extremely happy.” He was sent a letter by the team saying that it had been decided there were certain people who were not going to get rings. He could have called George Steinbrenner and asked, “but that’s just not the person that I am.”

Fossas had married in 1981. His wife Pura (Purísima) Valdes was also a Cuban, whom he had met in Jamaica Plain. They have two children – daughter Keila, born in 1983, and son Mark, born in 1985. In 2022, both were working as teachers in Clover, South Carolina. Tony’s brothers are both in education as well. Misael was an All-American Division III runner in cross country and track and field. He currently lives in Massachusetts and serves as a counselor at Dudley-Charlton Regional School District school, as well as Track and Field coach at Nichols College. John Fossas is principal of the Hollywood Hills Elementary Schools in Broward County, Florida.

In October 1999, Fossas started coaching his son Mark, who was at Piper High School in Sunrise, Florida. He coached pitching there for three years until Mark graduated. It was a “lot of fun with the kids” but “possibly the hardest job that I’ve ever done, dealing with parents.” He got an offer as pitching coach for Florida Atlantic University, just 15 minutes from his home, and worked there 2005-2008.

He then spent more than a decade working with the Cincinnati Reds in their minor league system, beginning with the Dayton Dragons 2009-2011, moving on to Billings in 2012, and then back to Dayton in 2013 and 2014. He was Daytona’s pitching coach in 2015. In 2018 he was the minor league pitching coordinator for the Reds, but with an organizational change, he wound up at Pensacola. One of the tasks the Reds had assigned him was to help Aroldis Chapman with his assimilation to the United States after Chapman had defected from the Cuban national team and signed with Cincinnati. “They wanted me to sponsor him, to show him how to go to restaurants and adjust to a new country, a new culture and life here as a pro.”21

Fossas was diagnosed with prostate cancer in February 2020 and had the gland removed. Two years later, he was cancer-free, and had retired from baseball. “I’m home now,” he said, “I’m feeling good. I’m getting exercise and spending time with my wife and kids. I had a good run, and now I’m home.”

Has he ever gone back to visit Cuba? “No, before he passed away, I made my father a promise that I would never go to Cuba until Cuba was free.”

Last revised: December 9, 2022

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, SABR.org, and the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball.

Notes

1 There were, of course, other times when Fossas faced more than one batter because there were two in a row who hit left-handed, but in 166 games he truly faced only one. That comes to more than 29% of the games in which he appeared.

2 Tom Archdeacon, “Dragons’ Fossas still inspired by dad,” Dayton Daily News, June 14, 2014. https://www.daytondailynews.com/sports/baseball/arch-dragons-fossas-still-inspired-dad/6zYHi4UvegncvXZmKOFiBM/ Accessed November 22, 2021.

3 Archdeacon.

4 Author interview with Tony Fossas on February 13, 2022. Unless otherwise indicated, all unattributed quotations come from this interview.

5 Archdeacon.

6 Peter Gammons, “Dream takes root,” Boston Globe, April 26, 1991: 29, 33.

7 See a summary of Kaplan’s life at https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/bostonglobe/name/howard-kaplan-obituary?id=2010781. Accessed February 15, 2022.

8 Fossas interview February 2022.

9 David Cataneo, “Fossas finishes his homework,” Boston Herald, February 13, 1991: 23.

10 Gammons, “Dream takes root.”

11 Thanks to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts and Scouting Research Committee.

12 Thomas Van Hyning, Puerto Rico’s Winter League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1995), 163.

13 Rick Hummel, “‘Mechanic’ Fossas Gives Cardinals Great Service,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 22, 1995: C6.

14 Steve Buckley elicited some information about how Fossas used to sneak into the ballpark. Steve Buckley, “Brewers’ Fossas going back to Fenway home,” Hartford Courant, June 29, 1989: C1A.

15 Cardinals GM Walt Jocketty signed Fossas to a minor-league contract the day after saying, “I’ve never been a big Tony Fossas fan.” Rick Hummel, “After Playing Musical Chairs, Jocketty Focuses on Fine-Tuning,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 10, 1995: 5C. The signing was reported in the April 11, 1995, Post-Dispatch.

16 “Survival Artist,” Sports Illustrated, March 12, 1996.

17 Fossas interview February 2022.

18 Duros frios were ice cubes with chocolate inside, made by his mother. “I sold them at the bus station and on the street, anywhere I could for a penny,” Archdeacon, “Dragons’ Fossa still inspired by dad.”

19 Fossas interview February 2022.

20 “I was 42,” he said.” I was at the end of my career and couldn’t pitch the way I had for St. Louis or Boston. I wanted to give back to Mr. Steinbrenner for what he did for me, but I couldn’t.” Archdeacon, “Dragons’ Fossas still inspired by dad.”

21 Archdeacon.

Full Name

Emilio Antonio Fossas Morejon

Born

September 23, 1957 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.