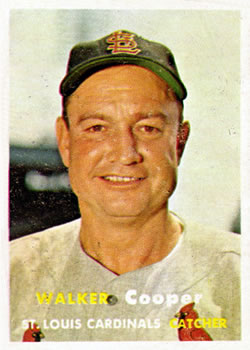

Walker Cooper

In his prime in the 1940s, Walker Cooper was thought to be the best catcher in baseball and the game’s strongest man. At 6-foot-3 and 220 pounds, he was an intimidating presence behind the plate and, in addition, possessed one of the strongest and most accurate arms in the National League. He was destructive at the plate as well, hitting for power and for high average.1 He was named to every National League All-Star team from 1942, his second full season, through 1950 with the exception of 1945 when there was no All-Star game because of World War II (Cooper was in the Navy in any event).

In his prime in the 1940s, Walker Cooper was thought to be the best catcher in baseball and the game’s strongest man. At 6-foot-3 and 220 pounds, he was an intimidating presence behind the plate and, in addition, possessed one of the strongest and most accurate arms in the National League. He was destructive at the plate as well, hitting for power and for high average.1 He was named to every National League All-Star team from 1942, his second full season, through 1950 with the exception of 1945 when there was no All-Star game because of World War II (Cooper was in the Navy in any event).

He was also named to The Sporting News Major League All-Star team in 1943, 1944, and 1947. In 1943 Cooper finished second to teammate Stan Musial in the National League MVP voting on the strength of his .318 batting average and 81 runs batted in in 112 games. He formed a famous brother battery with older brother Mort Cooper and the two helped lead the St. Louis Cardinals to consecutive pennants in 1942, 1943, and 1944. In two of those years, 1942 and 1944, the Cardinals were World Series champions.

William Walker Cooper was born on January 18, 1915, in Atherton, Missouri, a farming community about 25 miles east of Kansas City. He was the third of six children, five sons and a daughter born to Robert and Verne Cooper, both Missouri natives. Robert, a rural mail carrier and farmer, was a former sandlot pitcher who helped foster his sons’ interest in baseball from an early age.2 Walker recalled as a boy getting up at 5 a.m. or earlier, putting in 12-to-14-hour days working on his dad’s farm, grabbing supper and then heading out to the pasture to play baseball.3 Walker was first a pitcher in grade school but when Mort, who was catching, got clipped by a foul tip on his elbow and tore off his chest protector and mask and refused to continue, the two switched positions.4

The Coopers’ high school did not field a baseball team so the boys played in the highly competitive Ban Johnson American Legion League in Kansas City. Before one game, their father, who was coaching third base, told the boys that there wouldn’t be any supper unless they both hit home runs. According to the story, both sons did hit homers with a man on base in a 4-0 win and so dinner was waiting.5

Walker Cooper signed his first professional contract with the Kansas City Blues of the American Association in 1934. The Blues shipped him to Des Moines in the Class A Western League but there he drew his unconditional release. Older brother Mort was in the Cardinals organization and on his recommendation the club signed the 19-year-old Walker and sent him to the Rogers (Arkansas) Cardinals in the Class D Arkansas State League for 1935.

In Rogers, Cooper made only $40 a month6 but displayed what was to come, batting .359 with 14 home runs in 91 games and making the league All-Star team. Surprisingly, that performance only earned Cooper a promotion to Class C for 1936. Playing for the Springfield (Missouri) Cardinals, he batted .280 in 129 games and 486 at bats.

After the season on October 31, Cooper married Doris Triplett of Independence, Missouri.7 The couple would have two daughters, Sara and Jane, and would be married for 54 years until Cooper’s death in 1991.

Cooper jumped all the way to the Sacramento Solons in the Pacific Coast League in 1937 where he hit .266 in 83 games for a pennant-winning club. After starting 1938 with the Solons for four games, Cooper split the season between the Houston Buffs in the Texas League where he caught up with brother Mort, and the Mobile Peaches in the Class B South Atlantic League where under manager Milt Stock, he batted .288 in 233 at bats.8

Cooper again went to spring training with Houston in 1939, but clashed with the Buffs’ new manager Eddie Dyer and ended up in Class B again, this time with the Asheville Tourists of the Piedmont League.9 There Cooper established that he was ready for tougher competition as he batted .336 in 130 games for a championship club. That performance earned him a promotion to the Columbus Red Birds in the American Association for 1940. Now 25 years old and in his sixth full minor league season, he hit .302 in 131 games for Columbus and was rewarded with a late season call-up to the parent Cardinals.

St. Louis manager Billy Southworth first inserted Cooper in the lineup on September 25 in Sportsman’s Park in the second game of a doubleheader against the Cincinnati Reds, who were headed to their second consecutive National League pennant. Batting eighth in the line-up against Reds’ ace Bucky Walters, Cooper, in his first major league at bat, singled sharply to center with two outs in the bottom of the second to drive in Johnny Mize from third base. The blow tied the score at 1-1 in a game the Cards eventually won 4-3. Cooper finished the day one for two with a walk.

Cooper’s first game behind the plate also marked the first appearance of the Cooper brothers battery, as Mort Cooper relieved starter Ira Hutchinson in the seventh inning and pitched 2⅔ innings of scoreless baseball to finish the game. Mort was by now in his third season with St. Louis but had yet to emerge as the star he would later become during the war years.

Walker Cooper caught most of the games the last week of the season, including a 6-0 six-hit shutout tossed by brother Mort in the season’s finale.10 In six games in his big-league trial, Cooper went 6 for 19 for a .316 batting average. In his five starts behind the plate, the Cards were a perfect 5-0.

In one of those late season games, Cooper was called out on a called third strike by home plate umpire Babe Pinelli. Cooper took umbrage and said, “You blind so-and-so, I fought like hell to get out of the minor leagues and come up here, and you major leaguers are just as bad as the umpires in the minors.”

Pinelli said, “Why, you fresh rookie. You just get over there and don’t say nothin’.” According to Cooper, he just did that and rarely had trouble with the umpires afterwards.”11

Cardinals’ manager Southworth thought Cooper was a natural leader with instinctive baseball smarts, so it was not a big surprise when he won the regular catching job out of spring training in 1941.12 Cooper got off to a strong start at the plate and was hitting as high as .357 in early May when an 0-for-19 slump reduced his average to .246. Even worse, a home plate collision on May 18 with Hal Marnie of the Phillies knocked him out of action for seven weeks with a dislocated collarbone and injured shoulder.13 He returned to action on July 12 and, sharing the catching duties with veteran Gus Mancuso,14 again hit well. A three-hit day on July 27 raised his average to .322. But Cooper tailed off to a final .245 average in 68 games as the Cardinals finished in second place, 2½ games behind the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Although 27 years old, the strapping right-handed-hitting Cooper had yet to display much power at the plate in the big leagues. He finally hit his first major league home run on August 27 off the Giants’ Jumbo Brown. For the year, he drove in 20 runs in 200 at bats, with nine doubles, a triple, and that one home run. With the US entrance into World War II in December, Cooper, married with a child, was temporarily at least deferred from service, but in addition, his shoulder injury from the collision at home plate qualified him for only limited military duty and also made him safe from military service at least for the near term.15

Branch Rickey was the Cardinals general manager, known for his penny-pinching ways. When Cooper went in after the season to sign his contract for next year, he made it known that he wasn’t going to sign for the amount Rickey had offered him. When Cooper rose to leave, Rickey told him, “Walker, when you come back, it will be less.” Cooper must have believed Rickey, because he sat down and signed.16 Later, when Cooper was an established All-Star, he proved to much less pliable in salary negotiations.

The 1942 season turned out to be a banner one as the Cooper brothers’ battery came into their own and, helped by a rookie outfielder named Stan Musial, led the Cardinals to a World Championship. The “St. Louis Swifties,” as they were called,17 are often considered one of the best in baseball history.18 They won 43 of their final 51 games and 106 overall to just nip the Brooklyn Dodgers for the National League pennant. Walker Cooper hit .281 in 125 games behind the plate and was the starting catcher for the National League in the All-Star game.19

With his steady hand behind the plate, he helped guide brother Mort to a 22-7 record, a minuscule 1.78 earned run average, and the Most Valuable Player Award in the National League. Mort tended to lose his temper when things went wrong, but Walker could usually get his brother to chuckle and get back on track by yelling, “Don’t get red out there now.”20

Cooper quickly established himself as an outstanding bench jockey. Dodgers’ manager Leo Durocher was thoroughly disliked by the Cardinals and the oft-told story was that Durocher had stolen Babe Ruth’s watch out of his locker when the two were teammates on the New York Yankees. As a result, whenever Durocher began an argument during a game, which was often, Cooper would wave a watch at him from the dugout and yell, “Look at the watch, Leo. It’s Ruth’s watch.”21 Later after Durocher married actress Laraine Day, Cooper would shout, “Where does Laraine hide her jewelry at night?”22

Heading into the 1942 Series against the Yankees, Cooper was compared very favorably in the press to the Yankees’ future Hall of Fame catcher Bill Dickey.23 Even with their .688 winning percentage, the Cardinals, however, were decided underdogs to the Yankees, who had won 103 games. After losing the first game, however, the Cardinals came back to win four straight to upset the Yankees. Cooper went 6 for 21 (.286) with four RBIs and picked Joe Gordon off second to kill a ninth-inning Yankee rally in the deciding Game Five.24

With the average age of 26, the Cardinals were the youngest team to win the World Series, at least since before World War I.25 Although the club lost several key players to military service after the season,26 heading into 1943 they still had both Coopers, Stan Musial, Marty Marion, and Whitey Kurowski and were odds-on favorites to defend their championship. The Coopers both reportedly signed for $10,000, just behind Marion’s $12,000 but ahead of Musial who in his second year was to make $9,000.27

The Dodgers hung close to St. Louis for the first half of the season but the Redbirds literally ran away and hid the second half of the season and with 105 victories, winning the pennant by 18 games.

Cooper cemented his reputation as a tough guy in a late July game involving the Dodgers in St. Louis. The Dodgers’ Les Webber threw a couple of pitches behind Musial’s head, which incensed the entire Cardinals’ team. Cooper was the next batter and he hit a ground ball to the infield. He significantly jarred first baseman Augie Galan as he crossed the bag and Mickey Owen, the Dodger catcher who was backing up the play, decided to jump on Cooper’s back in a bear hug.28 According to Cardinal teammate Max Lanier, Cooper simply threw Owen on the ground like a rag doll and held him there.29

The next day Owen supposedly said, “I won’t do that again.”30

Cooper was rarely averse to trouble. If he caught a batter looking back to sneak a peek at his signs, he would spit tobacco juice on his socks.31 According to teammate Enos Slaughter, when the batter would step back from the plate and look at him, Cooper would say, “Well, what are you going to do about it?”

Even so, Slaughter said, “He was a great guy though. Wasn’t mean. Really very good natured.”32

His teammates called Cooper “Muley” out of respect for his great strength and endurance, and perhaps due to his stubbornness. Musial said, “When Big Coop was on your club, you didn’t have to worry about squabbles with anybody else, because he was in all of them.”33

Cooper did have a temper and sometimes did not like to have his picture taken. Teammate Harry Walker recalled a couple of times when Cooper physically threw photographers out of the clubhouse when they persisted in trying to take his photo. Walker remarked, “That’s why I was scared to room with him.”34

Even the dog days of a St. Louis summer didn’t seem to faze Cooper, who finished 1943 with a .318 batting average, third highest in the league, and 81 runs batted in. His .463 slugging average was third best in the circuit, all the more remarkable given that he hit only nine home runs. For his efforts he finished second in the National League MVP voting behind teammate Musial, who hit .357 to run away with the batting title.

The Cardinals again faced the Yankees in the World Series. The Yankees, who had lost Joe DiMaggio, Phil Rizzuto, and Tommy Henrich to military service, still had won the American League pennant by 13½ games. In Game One in Yankee Stadium, the Cardinals lost 4-2 as Spud Chandler bested Max Lanier. Cooper, batting clean-up, went 1-4.

Mort Cooper was scheduled to start Game Two the following afternoon. Before the game, the Coopers’ older brother Robert called the Cardinals’ hotel in New York and managed to get ahold of their manager, Billy Southworth. Robert told Southworth that the Coopers’ father had died suddenly that morning of a heart attack while putting on his shoes. Southworth broke the news to Walker and the two of them decided to tell Mort before the game. The brothers then had to decide whether to catch the first plane back to St. Louis or stay and play the game. They decided to stay because they knew that is what their father would want. Mort pitched and won the game 4-3 with his brother behind the plate as usual.35 Walker caught the last out of the game, a foul pop-up toward third off the bat of Joe Gordon that “jiggled in his glove a little, he squeezed it so hard.”36

Although the brothers had not discussed winning one for their father before or during the game, afterwards in the clubhouse Walker said, “We gave that one to Dad.”37 After the Cardinals returned to St. Louis for Game Three, Walker carried his father’s unused game ticket in his pocket and the Cardinals’ ushers had made sure no one sat in that seat.38

Unfortunately, the Cardinals dropped that game and two more to the Yankees at Sportsman’s Park and the finale at Yankee Stadium to lose the Series four games to one. Walker Cooper hit .294 but failed to drive in a run. In the final game, he broke a finger on his throwing hand on a foul tip off the bat of Frankie Crosetti.39

When the brothers returned home for their father’s funeral they found two large sprays of flowers on the casket, one on the top from the Cardinals and one at the bottom from the Yankees.40

Cooper had all winter to heal his broken finger but on November 17 he took his physical exam and was told to expect to be ordered to report for military service in the near future.41

But heading into the 1944 season, Cooper’s induction orders did not come. He was 29 years old, so under the so-called 26 Rule he would not be called if the military could meet their draft quota from men 26 or younger. Since that quota was in fact met,42 the Cardinals promised to have another powerhouse ballclub, as they lost only Lou Klein and Harry Walker to military service from their 1943 starting lineup.43

True to form, the Cardinals led from the get-go. In the second game of a doubleheader on June 11 Cooper, Kurowski, and Danny Litwhiler hit back-to-back-to-back home runs on six pitches off former teammate Clyde Shoun, tying a major league record.44

Cooper, riding a 9-for-16 stretch, was selected to start his third straight All-Star game along with five of his teammates .45 The National League won the game 7-1 in Pittsburgh to break a three-game losing streak as Cooper, batting cleanup, went 2 for 5.

The Cardinals continued their onslaught in the second half of the season and finished with 105 wins, 14½ games ahead of the Pirates. Cooper’s batting average got as high as .331 on August 23 after a five-game streak in which he went 15-for-19 (.789).46 During those five games he clubbed four home runs, three doubles, and drove in nine runs. For the season, Cooper batted .317 in 112 games with a career-high 13 home runs and 72 runs batted in.

The Cardinals faced the upstart St. Louis Browns in the “Streetcar Series,” the only one ever held between both St. Louis teams. The Browns led the league in 4-F players, in the first ever Streetcar World Series.47 All games were held at the stadium both teams shared, Sportsmans’ Park. In Game One, George McQuinn hit a two-run homer off Mort Cooper to lead the Browns to a 2-1 victory. The teams split the next two games but the Cardinals roared back to win three straight and take the Series in six games. In the ninth inning of Game Four, Cooper hit a tremendous shot that hit the fence by the flagpole in center field on one hop, 425 feet from home plate for the hardest hit of the Series.48

In the decisive Game Six, Cooper had two hits and a walk in four trips to the plate. For the Series he hit .318, behind only Emil Verban’s team-leading .412.49

Cooper was now widely considered the best catcher in baseball, whether in or out of the service, but 1945 would be a year of tumult and change for him.50 He and brother Mort were unhappy when the Cardinals’ owner Sam Breadon re-signed them each to contracts for $12,000 annually, the same amount they had been making the last three years. That amount was the maximum allowed under the wartime Wage Stabilization Act without special government approval. The brothers became upset when they learned that Breadon had offered 1944 MVP Marty Marion $13,500, pending government approval. The brothers responded by demanding $15,000 and refused to budge when Breadon offered to match Marion’s salary.51

Cooper now 30, was quoted as saying, “You know you have to make your money over just a few years in baseball.”52 He grudgingly started the 1945 season with St. Louis, batting .389 in four games, before his induction for limited service duty with the Navy on May 1 at the Jefferson Barracks Army Base in St. Louis.53 One writer lamented his loss, writing that Cooper was “a giant who gave you the impression he was carrying most of the Red Birds on his tremendous shoulders, so apparent was his domination of the St. Louis team.”54

On May 8, V-E Day, Cooper made his debut behind the plate for the powerful Great Lakes Naval Station Bluejackets baseball team. Playing against the University of Illinois in Champaign, the Bluejackets defeated the Illini 7-3 behind the pitching of fellow new inductee Denny Galehouse, whom Cooper had faced in the ’44 World Series.

Cooper also teamed with All-Star Cleveland Indian pitcher Bob Feller, back from 18 months of combat duty on the battleship Alabama in the Pacific, that summer. In July, Cooper caught Feller’s no-hitter against the Ford All-Stars and four nights later was behind the plate again as Feller threw a three-hit shutout against the Chicago Cubs. Afterward Feller said, “Before the Cub game we got in a huddle and Cooper gave me the lowdown on the Cub hitters and we had them on a string.”55

For the summer, Cooper batted .327 in 27 games with 10 home runs, including three in one game, as he helped the Bluejackets to a 25-6 record against a mix of military, minor league, major league, and college opposition.56

In addition to his salary dispute, two other issues complicated Cooper’s return to the Cardinals after his discharge. First, brother Mort, who was 4-F, had left the team about a month into the season, still in a snit over his salary dispute. Breadon responded by trading him to the Boston Braves in late May.57 After the season, the Braves had then hired manager Billy Southworth away from the Cardinals by offering him an almost unheard of salary of $50,000.58 Breadon in turn hired former farm director and minor league manager Eddie Dyer to succeed Southworth. The problem was that Dyer was not Walker Cooper’s favorite by a long shot, stemming from their clash in Houston during spring training in 1939.59 Even so, Dyer very much wanted Cooper to remain with St. Louis, but had a hard time convincing Breadon.60

The upshot was that on January 5, 1946, while Cooper was still in the Navy, Breadon sold his catcher to the New York Giants for $175,000.61 While Breadon’s motives for selling the best catcher in baseball were never entirely clear, $175,000 was a lot of money (more than $2 million in 2020). It was the largest sum the Giants had ever paid for a player and the third highest cash-for player deal to that time.62 One theory for the sale is that the Cardinals thought that 20-year-old Joe Garagiola, whom they had signed in 1944 off the St. Louis sandlots was going to be a star behind the plate.

Years later Garagiola said, in typical self-deprecating style, “I was supposed to fill Walker Cooper’s shoes… my best day, I could never be Walker Cooper. But that’s what people expected.”63

Stan Musial and Marty Marion were dismayed by Cooper’s departure.64 According to teammate Enos Slaughter, Breadon’s sale of Cooper was the biggest mistake he ever made. Slaughter said, “I honestly believe that with that tough raw-boned catcher behind the plate for us instead of for the Giants, we could have remained a dynasty for another five or six years.”65

Breadon could not even escape criticism for the sale during a testimonial dinner in his honor on the last night of the season. On that occasion an inebriated J. Roy Stockton, the well-known St. Louis sportswriter, told him, “Sam, it looks like you sliced the bologna a little too thin.”66 The Cardinals needed a postseason playoff victory over the Dodgers to get to the World Series, where they beat the Red Sox.

Cooper wasn’t released from the Navy until the 1946 spring training was nearly over and was admittedly out of shape upon joining the Giants in early April, remarking after hitting a triple in an exhibition game against the Washington Senators in Griffith Stadium, “I ran it all uphill.” He said he was glad to get the triple, “but I wasn’t so glad by the time I got to third.”67

Once the season started, Cooper rounded into shape and was named team captain.68 He was hitting .364 on April 25 when he fractured the pinky finger on his throwing hand on a foul tip off the bat of Bama Rowell in the Polo Grounds.69 Although he missed five weeks, he was still chosen to start his fourth All-Star Game.70 In the second half of the season Cooper battled more injury problems, including a serious leg infection. He finished with a .268 average in 87 games for the Giants who ended up in the cellar, 36 games behind the pennant-winning Cardinals. While many believed the 32-year-old was on the downside of his career, he proved the doubters wrong in 1947, turning in one of the best offensive seasons for a catcher in baseball history. In 140 games, Cooper hit .305 with 35 home runs (his previous career high had been 13) and 122 runs batted.71 Cooper, along with Johnny Mize, Willard Marshall, Sid Gordon, and Bobby Thomson, was part of a Giants power surge the lifted them from the cellar to fourth place as the team set a then Major League record with 221 home runs.

Once the season started, Cooper rounded into shape and was named team captain.68 He was hitting .364 on April 25 when he fractured the pinky finger on his throwing hand on a foul tip off the bat of Bama Rowell in the Polo Grounds.69 Although he missed five weeks, he was still chosen to start his fourth All-Star Game.70 In the second half of the season Cooper battled more injury problems, including a serious leg infection. He finished with a .268 average in 87 games for the Giants who ended up in the cellar, 36 games behind the pennant-winning Cardinals. While many believed the 32-year-old was on the downside of his career, he proved the doubters wrong in 1947, turning in one of the best offensive seasons for a catcher in baseball history. In 140 games, Cooper hit .305 with 35 home runs (his previous career high had been 13) and 122 runs batted.71 Cooper, along with Johnny Mize, Willard Marshall, Sid Gordon, and Bobby Thomson, was part of a Giants power surge the lifted them from the cellar to fourth place as the team set a then Major League record with 221 home runs.

In late June Cooper tied a National League record by slugging seven homers in six games.72 He tied the record in a game in which brother Mort, traded to the Giants earlier in the season, won his first game for the Giants.73 Walker was the overwhelming choice to start behind the plate for the National League in the All-Star game, his fifth straight selection.74

During the season, Cooper earned a reputation for hitting Ewell “the Whip” Blackwell like he owned him. Blackwell was 6’6” and threw sidearm, and so was notoriously tough on right-handed hitters like Cooper.75 When teammate Whitey Lockman asked Cooper about his success against Blackwell, with no false modesty Cooper told him that he was bailing out just like everyone else and hitting Blackwell’s mistakes inside. He said, “I don’t take any strikes against this guy!”76

His banner 1947 season earned Cooper a raise to $30,000 and status as the highest paid catcher in the big leagues. In 1948, however, he injured his knee in just the second game of the season in when he crashed into Bobby Bragan of the Dodgers trying to score. He tried to play through the injury but after about 10 days agreed to undergo surgery to remove bone chips in his knee.77 He was able to pinch-hit in six weeks and was back behind the plate late June. For the season, Cooper managed a .263 batting average with 16 homers and 54 RBIs in 91 games. The Cardinals were still lamenting his loss as they finished in second place in a season when all three of their catchers hit under .200 and their pitching staff struggled.78

By now the veteran catcher had earned a reputation as one of baseball’s best practical jokers and pranksters.79 One of Cooper’s favorite tricks was to get into a teammate’s locker and tie his baseball undershirt into as many as 25 knots. He was also known to nail teammate’s shoes to the floor with a sizeable spike in each.80 He was adept at giving hotfoots and reportedly one of his favorite pranks was to sit in a hotel lobby and set his newspaper on fire. With the Giants, Cooper kept Manager Mel Ott quite literally on his toes with hotfoots, putting lighted cigars in Ott’s hip pocket, and even snipping off the pocket lining just as the manager was taking the lineup cards to the plate.81 Unlike most catchers who used a handkerchief or sponge in their glove to absorb fastballs, Cooper preferred a woman’s falsie.82

Walker Cooper was also one of the quickest wits around during his playing days. With the Giants in 1947, Sid Gordon, Johnny Mize, and Cooper hit successive homers on five pitches. Buddy Blattner, a utility infielder with a .247 lifetime batting average, was the next batter and hit the dirt on the first two pitches, both high and tight fastballs. When Blattner came back to the bench after a making a routine out, Cooper told him, “I’ll say one thing, Blattner, they really respect you.”83

In November after the 1948 season, Cooper had additional surgery on his balky knee which enabled him to be ready for the start of the 1949 season.84 But he struggled at the plate and could not get his average above .200 until a month into the season. Then, on June 13, the Giants gave up on Cooper, trading him to the Cincinnati Reds for Ray Mueller in a swap of veteran catchers. After the trade, Cooper almost immediately came to life at the plate and hit .280 in 82 games for the Reds for the rest of the season. Cooper’s resurgence was at least in part due to his relief in getting away from Leo Durocher, who had taken over as Giants’ manager in mid-season in the previous year.85 When he joined the Reds, he made little effort to hide to hide his disdain for Leo, telling a writer, “You might put down that [Cincinnati manager] Bucky Walters is a much more pleasant fella to play for than Durocher is.”86

The 34-year-old had his career day with the Reds on July 6 in Crosley Field against the Cubs, going six for seven with three home runs and 10 runs batted in as the Reds prevailed 23-6. His six consecutive hits tied a league record. On his seventh at bat, with a chance to break existing records, he lined out straight to shortstop Roy Smalley. According to Cooper, it was the hardest ball he had hit all day.87 Catching nearly every day, he smacked 16 of his 20 home runs for the Reds and raised his season average to .258 in 454 at bats. Along the way, he was again named to the National League All-Star team, although he did not appear in the game.

The Reds finished in seventh place in 1949, 30 games under .500. They completed the season by losing two games to the Pirates in Pittsburgh and, as Blackwell recalled, the train trip home to Cincinnati got more than a little raucous as the team celebrated the end of a long, losing season with beer and hard liquor that they had snuck on the train. At one point the team got so out of control that the conductor came back and threatened to disconnect their car from the train and put it on a siding if they didn’t quiet down. Cooper responded by telling the conductor, “I don’t know what your name is today, but it’s going to be shit tomorrow if you try that.” That was the last they saw of the conductor.88

Cooper got off to another slow start in 1950 and the Reds, not learning from the Giants’ mistake the year before, traded him to the Boston Braves for infielder Connie Ryan on May 10. Cooper was hitting only .191 at the time of the trade but, after going five for nine in his first two games with the Braves, took over as the regular backstop and hit .329 for them in 102 games. He was again named to the National League All-Star team as he helped the Braves finish in fourth place.

Although 36 years old, Cooper had an almost identical year in 1951, sans the slow start. In 109 games, 90 of which were behind the plate, he again batted .313 as the Braves finished fourth for the second year in a row. He increased his home run total to 18 and amazingly struck out only a like number of times in 374 plate appearances. Cooper was snubbed for the All-Star game, even though he was batting .309 at the break. It broke a string of eight straight All-Star selections. He was the starting catcher in six of those games and batted a cumulative .333 in All-Star competition.

In 1952, Cooper slumped to a .235 average with 10 home runs in 102 games, 89 of which he caught. During spring training in 1953, the Braves moved suddenly to Milwaukee and Cooper went with them, although at 38 he was supplanted as the regular catcher by Del Crandall.89 As an original Milwaukee Brave, Cooper was used mainly against left-handed pitchers and hit only .219 in 53 games for an up and coming squad that finished second in the National League.

In 1952, Cooper slumped to a .235 average with 10 home runs in 102 games, 89 of which he caught. During spring training in 1953, the Braves moved suddenly to Milwaukee and Cooper went with them, although at 38 he was supplanted as the regular catcher by Del Crandall.89 As an original Milwaukee Brave, Cooper was used mainly against left-handed pitchers and hit only .219 in 53 games for an up and coming squad that finished second in the National League.

With Crandall on the scene, the Braves gave the 39-year old backstop his unconditional release after the 1953 season. Cooper’s career was winding down, but he still found work as a backup catcher and pinch-hitter for four more years. In those seasons he was passed around to the Pirates, Cubs, and back to the Cardinals as a player-coach. On September 20, 1957, Cooper appeared in his last major league game and made it count, pinch-hitting for pitcher Morrie Martin in the top of the ninth in a game the Cardinals were losing to the Reds 5-4. With Eddie Kasko on second with the tying run, Cooper singled sharply to center off Tom Acker to tie the game. The Cardinals went on to win 7-5 in 10 innings.

At 42 and after 18 seasons, Cooper’s major league career was finally over. Cooper’s daughter Sara, the reigning Miss Missouri,90 was engaged to his young teammate Don Blasingame, so Cooper quipped “It’s time to quit when you’ve got a daughter old enough to marry a teammate.”91

But Cooper was not through playing baseball. In November 1957, he agreed to become player-manager for the Indianapolis Indians of the American Association, signing a two-year deal.92 The Indians finished sixth in an eight-team league in his first year at the helm with a 72-82 record. He put himself into 38 games, mostly as a pinch hitter, and hit .211 in 71 at bats. Indianapolis improved to 86-76 for 1959, finishing in third place in the league’s newly constituted East Division. Cooper made only two pinch-hitting appearances for the season to close out his playing career.

After spending 1960 as a coach with the last-place Kansas City Athletics under his former teammate Bob Elliott, 93 Cooper signed on for 1961 to the manage to Dallas-Fort Worth Rangers in the American Association.94 The Rangers were a farm club of the expansion Los Angeles Angels. Under Cooper, the team finished fifth in a six-team league with a 72-77 won-loss record. After scouting for several years, Cooper went to work for a truck rental company in Kansas City, commuting the 30 miles from his home in Buckner, Missouri.95 He kept his hand in baseball, managing the managing the Bell Pest Control team in the amateur Casey Stengel League in 1980.96 When he retired, he and his wife moved to Scottsdale, Arizona, in 1986, where he enjoyed playing golf, even though he never broke 100, and occasional quail hunting.97 Cooper underwent bypass surgery in 1981 and passed away on April 11, 1991 of respiratory illness in a Scottsdale hospital.98 He was 76 years old.

For his 18-year major league career,99 Cooper batted .285 and slugged 173 home runs with an OPS of .796. His career .464 slugging average is 11th all-time for catchers. In 5,076 plate appearances, Cooper struck out only 357 times and never more than 43 times in a season. Early in his career he possessed good foot speed, although the constant wear and tear from catching took its tool. Defensively, he had an excellent arm and threw out almost 45 percent of runners attempting to steal.

One of Cooper’s finest attributes was his ability to call a game and handle pitchers. Even early in his career, teammate Coaker Triplett was quoted as saying, “He’s the best fellow handling young pitchers I have ever seen.”100 Later in his career he often was in the line-up simply to catch a rookie pitcher, as he did in 1953 for Don Liddle’s first major league start. Liddle pitched a two-hitter for the Braves against the Cubs and largely credited Cooper.101

Cooper was known as one of the toughest of ballplayers and commanded great respect from his peers.102 Ransom Jackson, one of his teammates on the Cubs, remembered Cooper “as an easygoing guy but tough as a Mack Truck.”103 According to Braves’ teammate Andy Pafko, Cooper was a pillar of the clubhouse. Pafko said, “There was one person who always had the attention of the players when he spoke: Walker Cooper.”104

Cooper was also widely regarded as one of strongest men in baseball. Tommy Holmes of the Braves remembered the time that Cooper hit a grand-slam home run over the center-field fence in Braves Field against the wind on a drizzly night when the air was heavy. What was especially memorable was that Cooper’s bat broke into three pieces upon making contact.105

Although Walker Cooper was one of baseball’s strongest personalities, he played without much flash and dash. His career is sometimes downgraded because much of his prime occurred during the war years, but he continued to perform at a high level in the late 1940s and early 1950s and made a total of eight All-Star teams. Cooper was simply an outstanding ballplayer over a long and distinguished career.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Warren Corbett and David H. Lippman and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 David Pietrusza, Matthew Silverman, and Michael Gershman, eds., Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Total/Sports Illustrated, 2000), 237.

2 Gordon Campbell, Ninth Series of Famous American Athletes of Today (Boston: L.C. Page & Company, 1945): 104.

3 Roger Birtwell, “’Ol Walk Shows New Bounce as a Brave,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1951, 5.

4 Jerome M. Mileur, High-Flying Birds — The 1942 St. Louis Cardinals (Columbia, MO.: The University of Missouri Press, 2009), 94; Gregory H. Wolf, Mort Cooper biography for the SABR Bioproject at https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/9c707ace. Another version of the story is that Walker Cooper always caught and Mort always pitched until they decided to switch one day while playing semi-pro ball for the Independence (Mo.) Merchants. According to that version, Mort got hit by a batter’s swing while rushing forward to catch a pitch early when a runner was attempting to steal and refused to catch anymore. Arthur Mann, “Brother Battery — the Coopers,” Baseball Digest, October 1944: 2-3.

5 Campbell, 105.

6 Birtwell, 5.

7 Martha Jackson, “The Cooper Wives….Of Baseball and Independence, Mo.,” St. Louis Star-Times, September 30, 1942: 19.

8 Campbell, 106.

9 https://retrosimba.com/2016/01/07/a-stormy-relationship-between-walker-cooper-cardinals/

10 The losing pitcher was Dizzy Dean, who fell to 3-3 in his comeback attempt with the Chicago Cubs. Dean would make only two more big league appearances on the mound, a one inning stint in 1941 and, in what was mostly a publicity stunt, a four inning start as a member of the St. Louis Browns in 1947.

11 According to Cooper, he and the umpires were “buddy-buddy.” When telling the story, Cooper indicated that his exchange with Pinelli was after his first at bat in the major leagues, but since he didn’t strike out in his first game, it was more likely on September 28, 1940, which would have been his fifth big league game. Don Harris, “Walker Cooper Looks Back on an All-Star Career,” Baseball Digest, June 1990: 71.

12 John Klima, The Game Must Go On: Hank Greenberg, Pete Gray, and the Great Days of Baseball on the Home Front in WWII (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015): 77.

13 Mel R. Freese, The St. Louis Cardinals in the 1940s (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2007): 42.

14 The Cardinals had acquired the veteran Mancuso from the Dodgers in exchange for Mickey Owen in the offseason to help mentor Cooper. According to Cardinals’ pitcher Harry “Gunboat” Gumbert, “Those two always talked about catching. Their heads were always together.” Rick Van Blair, Dugout to Foxhole — Interviews with Baseball Players Whose Careers Were Affected by World War II (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1994), 70.

15 William B. Mead, Even the Browns: The Zany, True Story of Baseball in the Early Forties (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1978): 121; Bill Borst, The Best of Seasons: The 1944 St. Louis Browns and St. Louis Cardinals (Jefferson NC: McFarland & Company, 1995): 38, 91; Rob Rains, The St. Louis Cardinals (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992), 103.

16 Bobby Thomson with Lee Hieman and Bill Gutman, “The Giants Win the Pennant! The Giants Win the Pennant!” (New York: Zebra Books, 1991): 26.

17 They were so named by the famous New York World-Telegram cartoonist Willard Mullin. E.G. Fischer, “Billy Southworth’s St. Louis Swifties,” St. Louis’s Favorite Sport, SABR 22, 1992; Van Blair, 205.

18 Tom Meany, Baseball’s Greatest Teams (New York: A. S. Barnes and Company, 1949): 30-43.

19 Cooper caught the first six innings for the National League before being replaced by Ernie Lombardi. In a 3-1 loss, he was one for two at bat with a single in the third inning off Spud Chandler and an out on a bunt attempt in the sixth against Al Benton.

20 Mileur, 62; Mann, 5.

21 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis — A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: Avon Books, 2000), 228.

22 Thomson with Hieman and Gutman, 56.

23 “Critics Favor Card Catchers,” unidentified clipping dated September 25, 1942 in the Walker Cooper clippings file, National Baseball Library.

24 According to Marion, Cooper said, “Watch it Marty. We might try something.” Marion knew to be ready for a pick-off throw. Marty Marion as told to Lyall Smith, “Martin Marion,” in John P. Carmichael et. al., My Greatest Day in Baseball (New York: A.S. Barnes & Company, 1945): 171; Lyle Smith, “Marty Marion,” in Richard Peterson, ed., The St. Louis Baseball Reader (Columbia, MO, University of Missouri Press, 2006): 249; Bob Broeg with Jerry Vickery, The St. Louis Cardinals Encyclopedia (Lincolnwood, IL, Masters Press, 1998): 44; Mileur, 223-24; Golenbock, 245-46; Carmichael, 170-72.

25 Mileur, 2.

26 Cardinals’ players lost to the service for 1943 included Enos Slaughter, Terry Moore, Johnny Beazley, Frank Crespi and Whitey Moore.

27 Danny Litwhiler with Jim Sargent, Danny Litwhiler — Living the Baseball Dream (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006): 60; Golenbock, 257.

28 Donald H. Drees, “Brawl Stirs 30,599 as Cards Beat Dodgers, 7-1 and 5-4, St. Louis Star-Times, August 2, 1943, 18. According to Stan Musial, Cooper spiked Galan as he crossed first base, precipitating Owen jumping on Cooper. Stan Musial as to Bob Broeg, The Man Stan Musial, Then and Now (St. Louis: Bethany Press, 1977): 90.

29 Donald Honig, Baseball When the Grass Was Real (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, Inc., 1975): 215.

30 Golenbock, 243.

31 Klima, 97.

32 Donald Honig, Baseball Between the Lines (New York: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, Inc., 1976): 161; Enos Slaughter with Kevin Reid, Country Hardball — The Autobiography of Enos “Country” Slaughter (Greensboro, NC: Tudor Publishers, 1991): 64.

33 Robert Weintraub, The Victory Season: The End of World War II and the Birth of Baseball’s Golden Age (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2013):45-46.

34 Larry Powell, Bottom of the Ninth: An Oral History on the Life of Harry ‘The Hat’ Walker (San Jose: Writer’s Showcase, 2000): 56-7.

35 Bill Gilbert, They Also Served — Baseball and the Home Front, 1941-45 (New York: Crown Publishers, 1992): 103-104; John C. Skipper, Billy Southworth — A Biography of the Hall of Fame Manager and Ballplayer (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2013):129-30; Campbell, 108.

36 Mort Cooper as told to John P. Carmichael, “Morton Cooper,” in John P. Carmichael et. al, My Greatest Day in Baseball (New York: A.S. Barnes & Company, 1945): 233.

37 Gilbert, 104. According to Mort Cooper, his brother Bob got Mort on the phone by mistake and hung up when he heard Mort’s voice because Bob knew Mort was pitching in the World Series that day and didn’t want to him to know about their father’s death until after the game. Mort gave Walker a lot of credit for his being able to defeat the Yankees that day, saying, “He’s the kid that deserved any honor. He not only had the same burden to share that I did, as a brother, but he had to keep me together, too. I had to pitch. Walker had all the grief and me on top of it to shoulder. He was the strong man…carrying me along.” Carmichael, 229.

38 Ralph O’Leary, “Empty Seat For ‘Pop’ Cooper At Today’s World Series Game,” St. Louis Star and Times, October 11, 1943:18.

39 Freese, 106.

40 Carmichael., 230.

41 Freese, 107.

42 Freese, 113.

43 Emil Verban at second base and Johnny Hopp in center field were able to fill in admirably. In fact, Hopp batted .336, fourth highest in the National League.

44 Cooper’s and Kurowski’s came on consecutive pitches while Litwhiler’s came on a two-strike count. Borst, 100-101; Freese, 117.

45 They were Musial, Marion, Kurowski, Max Lanier, and George Munger. Mort Cooper, who was 10-3 and would win 22 games in 1944, was somehow left off the team. Munger, on the other hand, was replaced by Jim Tobin of the Boston Braves because Munger’s induction into the army was scheduled for the day of the game. Instead, Munger pitched for the military that night and defeated the Lambert Field Navy Wings 2-1. David Vincent, Lyle Spatz, and David W. Smith, The Mid-Summer Classic: The Complete History of Baseball’s All-Star Game (Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press, 2001): 68.

46 Borst, 178.

47 The Browns started the season with 18 4-Fs and 13 completed the season with the team. Mead, 141.

48 The Browns nailed Cooper at the plate, trying to stretch the hit into an inside-the-park home run, Borst, 248-49.

49 Although the Browns only hit .183 for the Series, their first baseman George McQuinn led all batters with a .438 average.

50 After the World Series, Connie Mack said, “Walker Cooper rates as the best catcher in baseball today.” Unidentified clipping titled “Cooper Top Says Mack,” dated October 28, 1944 in the Walker Cooper clippings file, National Baseball Library.

51 Roger S. Gogan, Blue Jackets of Summer — The History of the Great Lakes Naval Baseball Team, 1942-1945 (Kenosha, WI: Great Lakes Sports Publishing, 2008): 147-48; Richard Goldstein, Spartan Seasons: How Baseball Survived the Second World War (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1980): 148-49.

52 Goldstein, 149.

53 Cooper was accepted for limited service in November 1943 but was told he would be called up later to fill a military quota. “Walker Cooper Accepted,” unidentified clipping dated November 19, 1943 in the Walker Cooper clippings file, National Baseball Library.

54 He also wrote that Cooper left “an aching void in the heart of Manager Billy Southworth…“Franklin Lewis, “They Don’t Want to Be Catchers,” Baseball Digest, July 1945: 1.

55 Gogan 161.

56 Gogan, 203.

57 Mort Cooper was traded for pitcher Red Barrett and $60,000. It turned out to be a terrific trade for the Cardinals as Barrett went 23-12 while Cooper, saddled with a sore arm, went 9-4 for Boston but was limited to 101 innings. James D. Szalontai, Teenager on First, Geezer at Bat, 4-F on Deck: Major League Baseball in 1945 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2009): 45-46.

58 Skipper, 145.

59 According to Marty Marion, Dyer expressed regret that Cooper felt that way, but didn’t think he was the reason Cooper was sold to the Giants. Golenbock, 366.

60 Rains, 110-11; Golenbock, 366.

61 John Drebinger, “Giants Pay $175,000 for Walker Cooper of the Cardinals,” New York Times, January 6, 1946.

62 “Outbid Braves, Phils for Top N.L. Backstop,” Brooklyn Eagle, January 6, 1946.

63 Cynthia J. Wilbur, For the Love of the Game — Baseball Memories From the Men Who Were There (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1992): 25.

64 According to Musial, “[W]ith John Mize [who was traded back in 1941]and Walker Cooper in our lineup all those years, we would’ve been unbeatable. Really! So that’s one of the reasons we didn’t win more pennants.” Anthony J. Connor, Baseball for the Love of It, (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1982); Marshall, 90-91.

65 Slaughter with Reid, 81.

66 Marshall, 91.

67 Gilbert, 265.

68 Fred Stein, Mel Ott: The Little Giant of Baseball (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1999): 157.

69 Jerry Mitchell, “Loss of Cooper for 4 Weeks Tough Blow to Giants’ Hopes,” unidentified clipping dated April 26, 1946 from the Walker Cooper clippings file, National Baseball Library.

70 Cooper singled in his only at bat before being relieved by Phil Masi in a 12-0 American League shellacking of the Nationals.

71 Teammate Bobby Thomson was a rookie that year and later said that Cooper was for a time using a bat with small nails in it “until they made him stop.” It is unclear from the context whether Thomson was referring to spring training or early in the regular season. Norman L. Macht, They Played the Game: Memories From 47 Major Leaguers (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019): 244.

72 John, Drebinger, “Giants Top Phils As Coopers Shine in 14-6 Triumph,” The New York Times, June 29, 1947: 1; Jim McCulley, “Mort Explains Walker’s HR Spree,” New York Daily News, June 27, 1947: 57.

73 Mort Cooper, battling arm miseries and weight problems, finished the season with a 3-10 record and 5.40 earned run average.

74 Excluding 1945 when he was in the service.

75 Blackwell won 16 games in a row in 1947 and finished the season 22-8. Cooper hit one of only two homes run off Blackwell during his streak. Allen Lewis, Baseball’s Greatest Streaks (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1992): 156.

76 Brent Kelley, The Pastime in Turbulence: Interviews with Baseball Players of the 1940s (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2001): 175.

77 John Drebinger, “Cooper of Giants Awaits Operation,” New York Times, May 12, 1948; Joe Trimble, “Leo Sticks With Coop; Catcher Faces Knife,” New York Daily News, November 1, 1948: 84

78 James N. Giglio, Musial: From Stash to Stan the Man (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2001): 164.

79 Garth Garreau, Batboy of the Giants (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1953): 137.

80 Joe Garagiola, Baseball Is A Funny Game (New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1960):27; Paul Wick as told to Bob Wolf, Batboy of the Braves (New York: Greenburg Publisher, 1957): 38.

81 Fred Stein, Under Coogan’s Bluff, A Fan’s Recollection of the New York Giants under Terry and Ott (Chapter and Cask, 1979): 127.

82 John Heidenry and Brett Topel, The Boys Who Were Left Behind (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2006): 89-90.

83 Garagiola, 63

84 Trimble.

85 “Cooper Happier Away From Lippy,” New York Sun, June 29, 1949. When Durocher was hired, he even went around telling his teammates, “You’d better watch your wallets, guys.” Danny Peary, ed., We Played the Game: 65 Ballplayers Remember Baseball’s Greatest Era — 1947-1964 (New York: Hyperion, 1994): 67.

86 Cooper also told the same writer, “I’ve always thought that Durocher could ruin any good ball club.” “Cooper Happy Now, Rips Lip’s Handling of Giants,” unidentified clipping dated June 28 in the Walker Cooper clippings file, National Baseball Library.

87 Lester Biederman, “Scoreboard,” The Pittsburgh Press, May 16, 1954.

88 That same train stopped for what was supposed to be a 30-minute layover somewhere in West Virginia and Cooper and Doc Bohm, the Reds trainer, got off to round up some more beer. According to Blackwell, the train started again almost immediately, leaving the two behind. About 30 minutes later the train suddenly came to a screeching halt in the middle of nowhere. In front of the train, Cooper and Bohm were walking down the tracks toward the train, each carrying two cases of beer. They had hailed a cab and beaten the train to the next crossing and somehow presuaded the driver to straddle his cab on the tracks to make the train stop. Honig, 53-54.

89 Bob Buege, The Milwaukee Braves: A Baseball Eulogy (Milwaukee: Douglas American Sports Publications, 1988): 12-16.

90 Sara Cooper won the talent competition at the Miss America pageant by doing the Charleston. “Girl Wins Round Doing Charleston,” unidentified clipping dated September 6, 1957 from the Walker Cooper clippings file, National Baseball Library.

91 Cooper also said, “Everybody says just think how much money would result if they’d produce a boy who could hit like me and run like Blasingame. Heck, with the luck of the Coopers, he’ll run like me and hit like the Blazer.” Broeg; Musial as told to Broeg, 172. The Blasingames did have a son named Kent who played baseball at Texas Tech University and then professionally for three years.

92 Les Koelling, “Big Coop Named Playing Skipper of Indianapolis,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1957.

93 “Gordon Quits Tigers and A’s Let Elliot Go,” unidentified clipping dated October 3, 1960, from the Walker Cooper clippings file, National Baseball Library.

94 Dallas/Fort Worth general manager was Roy Johnston who had hired Cooper to manager Indianapolis in 1958. “Cooper New Dallas Pilot — Slaughter Gets Raleigh Job,” unidentified clipping dated March 8, 1961 from the Walker Cooper clippings file, National Baseball Library.

95 Broeg.

96 “Walker Cooper dead at 76,” undated clipping from the Kansas City Star in the Walker Cooper clippings file, National Baseball Library.

97 Harris, 72.

98 “All-Star catcher from 40’s, Walker Cooper, dies at 76,” Sports Collectors Digest, May 24, 1991.

99 For two of those seasons, 1940 and 1945, Cooper was only in the big leagues a brief time and appeared in only a handful of games.

100 https://retrosimba.com/2016/01/07/a-stormy-relationship-between-walker-cooper-cardinals/

101 Gene Fehler, When Baseball Was Still King — Major League Players Remember the 1950s (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2012): 101-02. Bob Buhl was also a rookie pitcher, that season. Cooper, in an effort to boost the youngster’s confidence, told him not to worry about signs but to just throw whatever he wanted. Buhl had developed a nasty slider and after he threw a couple that handcuffed the veteran catcher, chasing him to the backstop, Cooper went to the mound and said, “Kid, I think we’re going to need a sign for that one.” Peary, 215.

102 Peary, 213-14; Powell, 36, 56.

103 Jackson remembered a time when Cooper came into the clubhouse after the game with a big strawberry-red splotch on his rear end from sliding on the hard dirt infield. Instead of going to the trainer and getting some salve and a bandage for the wound, Cooper just picked up a bottle of rubbing alcohol, poured it on his hands and then splashed on his skin scrapped raw as several of his teammates became nauseous. Ransom Jackson, Jr. with Gaylon H. White, Handsome Ransom Jackson — Accidental Big Leaguer (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016): 176.

104 Joe Niese, Handy Andy: The Andy Pafko Story (Chippewa Falls, WI: Chippewa River Press, 2015): 168.

105 Gilbert, 103.

Full Name

William Walker Cooper

Born

January 8, 1915 at Atherton, MO (USA)

Died

April 11, 1991 at Scottsdale, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.