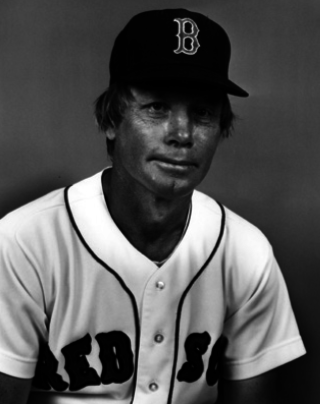

Walt Hriniak

Throughout his 12-year professional playing career, Walter John Hriniak (pronounced RIN-ee-ack) brought Gas House Gang-style intensity to the game. Typically wearing the filthiest uniform, he was dubbed “The Rat” for his tendency to “grovel around the dirt and grime and do anything to win a ballgame. ‘I don’t have the God-given ability of others, so I have to play like this,’” he modestly explained.1 If Hriniak had been born 50 years earlier, he would have fit right in with the likes of Joe Medwick, Frankie Frisch, and other rough-and-tumble players of that era. But in 1968-1969 Hriniak’s abilities got him a mere 99 major-league at-bats.

Throughout his 12-year professional playing career, Walter John Hriniak (pronounced RIN-ee-ack) brought Gas House Gang-style intensity to the game. Typically wearing the filthiest uniform, he was dubbed “The Rat” for his tendency to “grovel around the dirt and grime and do anything to win a ballgame. ‘I don’t have the God-given ability of others, so I have to play like this,’” he modestly explained.1 If Hriniak had been born 50 years earlier, he would have fit right in with the likes of Joe Medwick, Frankie Frisch, and other rough-and-tumble players of that era. But in 1968-1969 Hriniak’s abilities got him a mere 99 major-league at-bats.

Instead Hriniak turned this same Gas House intensity to the study of hitting and became one of the most famous – and often derided – instructors in baseball. For though his techniques enhanced the career of many with the God-given talent he once lacked, Hriniak’s methods – combined with a gruff, intense, no-nonsense style – afforded many detractors as well.

Hriniak was born on May 22, 1943, one of two children of Walter Edward and Ann Catherine (Gumaskas) Hriniak, in Natick, Massachusetts, 15 miles west of Boston. He was the grandson of Polish and Lithuanian immigrants. The Natick High School Redhawk was the All Bay State League Quarterback on the gridiron and the Bay State League Most Valuable Player on the hockey rink. But for the sandy-haired shortstop, baseball was where he particularly excelled:

- First freshman to play Natick varsity baseball since 1920.

- 1961 team captain and most valuable player.

- 1961 Massachusetts Gridiron Club Memorial Outstanding Player.

In 1960 Hriniak was selected to play in the showcase Hearst Sandlot Classic in Boston, a popular venue for major-league scouts. A year later the high-school senior paced the Redhawks with a .461 average. He was pursued aggressively by the Boston Red Sox, Philadelphia Phillies, San Francisco Giants, Pittsburgh Pirates, and Milwaukee Braves. Shortly after graduation, Hriniak signed a contract with Braves scout Jeff Jones and received an $80,000 bonus.

Assigned to the Eau Claire (Wisconsin) Braves in the Northern League (Class C), Hriniak quickly wrestled shortstop from second-year prospect Demetri Alomar (the older brother of Sandy Alomar Sr.). Despite a mere 267 at-bats Hriniak, the team’s youngest player, placed among the Braves leaders in RBIs (50), doubles (14), and batting average (.311). Significantly, he also placed among the leaders in walks, a practice he continued in subsequent campaigns. (This plate patience was one of the core principles Hriniak stressed as a coach years later.) In the Florida Instructional League after the season, he caught the attention of Milwaukee manager Birdie Tebbetts, who said, “[The Braves] have a club policy of developing our own, and have especially high hopes for … infielder Walt Hriniak.”2 His debut success earned Hriniak a spot on Milwaukee’s 40-man roster as the Braves’ youngest position player.

Named to the Florida Instructional League’s All-Star squad in 1962, Hriniak had less success with the Austin Senators in the Double-A Texas League the following spring. Unable to unseat shortstop Sandy Alomar, he settled in at second base. Though he was challenged at the advanced level – it was the first season Hriniak hit less than .300 – there was no indication the Braves intended to give up on their 20-year-old prospect. But circumstances outside the baseball diamond would limit Hriniak to 175 at-bats with the Senators in 1964.

On the morning of May 22, Hriniak and teammate Jerry Hummitzsch were in a celebratory mood. Hriniak was observing his 21st birthday while Hummitzsch was basking in the wake of his 10-inning, three-hit, 1-0 win over the Fort Worth Cats. They set out for a predawn fishing excursion when, cruising along the winding roads west of Austin, Hummetzsch lost control of his sports car. The pitcher was killed when the vehicle overturned. Thrown through the windshield, Hriniak survived but his head and chest injuries kept him in the hospital more than two months. He recovered sufficiently to participate in the Florida Instructional League after the 1964 season. Years later Hriniak stoically recalled, “I never thought the accident had anything to do with my not making the big leagues. It happened, and I had to deal with it.”3

Excluding a demotion to Class A in 1965, Hriniak remained with the Austin Senators into 1967. His middling offensive production slowed further promotion as he manned each infield position but first base. On April 21, 1967, Hriniak connected for a grand slam – his first homer in 134 games – in a 13-5 victory over the Albuquerque Dodgers. The blow rejuvenated his bat as the lineup’s former eighth-place hitter placed among the Senators leaders in most offensive categories. Once again predating his coaching success, the 24-year-old studiously analyzed his approach:

“I choked up a lot and got right on top of the plate. My back foot wasn’t but about six or seven inches from the plate and when you’re that close, if you’re not quick with the bat, they’ll saw you off with that inside pitch.”4

On July 13 Hriniak was pressed into service as an emergency catcher against the El Paso Sun Kings. He quickly proved his worth by gunning down three opposing baserunners, thereafter setting his course within the Braves organization. Promoted to the Triple-A Richmond Braves, Hriniak received as much play at catcher as he did the infield.

The 1968 season proved a watershed year for Hriniak. Reassigned to Shreveport, the Braves’ new Texas League farm team, he sustained a split finger early in the season that hampered his play behind the plate. Refusing to sit, he was positioned at third base until the finger healed. Meanwhile Hriniak’s batting stroke appeared fully restored when, after a 7-for-18 surge in August, he briefly led the league with a .313 average. The Topps Chewing Gum Company selected Hriniak as the Texas League’s August Player of the Month and, at the end of the season, Double-A All-West All-Star catcher. Arguably his most productive season in professional baseball, Hriniak’s successful campaign was carried out under the direction of manager Charlie Lau. The merger of the assiduous skipper and his hard-working disciple would prove profitable for years to come.

Lau was not the only person observing Hriniak’s triumphant campaign. The Braves – since relocated to Atlanta – took notice and selected the catcher as one of the team’s September call-ups. On September 10, 1968, Hriniak made his major-league debut, against the San Francisco Giants. The next day he collected his first two hits against Giants future Hall of Famer Juan Marichal while catching a four-hitter twirled by Braves righty Pat Jarvis. Atlanta manager Lum Harris offered lavish praise of the 25-year-old backstop, saying, “He called a good game. … Pat shook off very few pitches.”5 Harris’s admiration continued that winter as he received reports of Hriniak’s play in the Venezuelan League: “Our scouts say he is tearing up the winter league. … He is hitting well and throwing out everything that moves.”6 With the departure of Joe Torre in March, Hriniak appeared poised to take over the Braves’ 1969 catching responsibilities.

But in March 1969, in a near-repeat of the preceding year, Hriniak asked to play at second base while a broken bone in his right thumb healed. Catching duties fell to Bob Didier by default while Hriniak was placed on the disabled list to start the season. Fully recovered, Hriniak got little play – one hit in seven at-bats through June 4 – when he broke another finger and was placed on the disabled list a second time. Hriniak was still on the disabled list when, on June 13, he was traded to the San Diego Padres in a three-player swap for outfielder Tony González. Hriniak came off the disabled list on June 27 and was promptly inserted into the starting lineup. Four days later he was relegated to pinch-hitting after reinjuring the finger sliding into second base. Hriniak returned behind the plate on June 27 and thereafter shared backup catching duties with two younger prospects. When Hriniak walked off the field on September 30, he had no way of knowing it was his final appearance as a major-league player.

On December 5, 1969, while Hriniak was again toiling in the Venezuelan League, the Padres acquired catcher Bob Barton from the Giants. Though the move cemented the backup role behind catcher Chris Cannizzaro, Hriniak’s versatility made him a viable candidate as a utility player. He hung on until the next-to-last cut in spring training and was assigned to the Salt Lake City Bees in the Pacific Coast League. Moved to second base, with his gritty style of play he quickly captured the admiration of Bees manager Don Zimmer, who told sportswriters: “You are gonna love this guy. He battles every minute and will do anything in his power to help the club.”7 But 1970 proved to be Hriniak’s last season as a full-time player. On April 3, 1971, he was traded back to the Braves organization and released that summer. Unsure where to turn, Hriniak received an unexpected call from an old acquaintance.

On August 24, 1971, Montreal Expos general manager Jim Fanning signed Hriniak as a free agent.8 The Expos executive was very aware of Hriniak. He had been Hriniak’s manager in Eau Claire and was well aware of the player’s strong work ethic. In 1971 Hriniak played in a mere nine games for the Expos Triple-A affiliate at Winnipeg, but from the moment of signing, it appears, Fanning had another role in mind for the 28-year-old. In November Hriniak was signed as a player, coach, and manager, and his coaching career was launched. In 1972 he coached for the Double-A Quebec Carnavals until the New York-Pennsylvania League season began, when Hriniak took the managerial reins of the Jamestown Falcons. He continued in this capacity through 1973 while ushering in the careers of youngsters Larry Parrish and Gary Roenicke.9

Prior to the 1974 season Montreal announced Hriniak as manager of its West Palm Beach affiliate in the Florida State League (Class A). But when Larry Doby left the Expos, Hriniak was tapped to join the 1974 coaching staff. Serving as the team’s first-base coach, he wasted little time “earning” a two-game suspension and a $200 fine. Hriniak was accused of bumping umpire Art Williams in a June 1 game against the Braves. Manager Gene Mauch was outraged because he – like many Montreal players – felt Williams had been the aggressor. In Hriniak, Mauch likely saw the same feisty approach that he brought to the game. Hriniak remained an Expos coach under Mauch. After the manager was fired in 1975, Hriniak became the hitting coach for the Double-A Denver Bears and then manager of the Rookie League Lethbridge (Alberta) Expos. While with Lethbridge, Hriniak served a five-day suspension in July 1976 for “spraying an umpire with saliva.”10

At about the time Hriniak was serving his suspension, things were happening 2,500 miles to the east that would have a profound impact Hriniak’s career. The reigning American League champion Red Sox were suffering through a dismal campaign. In July Boston fired Darrell Johnson, the manager, and named third-base coach Don Zimmer to replace him. Though Zimmer would be forced to seek another residence – he was renting Hriniak’s Natick home – in October Zimmer tapped Hriniak as his bullpen coach, launching Hriniak’s 12-year term with the Red Sox.

Hriniak’s untiring work ethic quickly earned him the nickname Iron Mike. Until he broke a shoulder in 1978, Hriniak threw batting practice, earning the respect of his Boston teammates. But Hriniak’s lasting impact came through his work with the Red Sox batters. Though Johnny Pesky was Boston’s hitting coach through much of Hriniak’s 12-year stay, to many players Hriniak – under managers Zimmer, Ralph Houk, and John McNamara – was the de-facto hitting coach. Though afterwards one of Hriniak’s sharpest critics, in 1978 Red Sox icon (and avid fisherman) Ted Williams remarked, “[Hriniak has] done well here with the club. … Good teachers [like him] are worth their weight in swordfish.”11

Asked years later to explain his teaching methods, Hriniak bowed to his late mentor and manager Charlie Lau: “[I’m simply] carrying on the work of my friend, that’s all. It’s his stuff, I’m just teaching it.” Stressing the need to create good habits by hitting to all fields, Hriniak painted the alternative: “[O]nce you start trying to pull everything, the pitchers and the defense all know what you are going to do. You have to commit yourself to pitches a lot sooner and get farther out in front and you are more wide open for breaking stuff. The percentages are against you.”12 Though this flew in the face of Williams’s approach – an emphasis on a strong hip and torso rotation to whip the bat through the swing – Hriniak’s methods drew many backers.

Carl Yastrzemski was one such adherent. When Hriniak joined the Red Sox in 1977, Yastrzemski was already at an age (37) when players were typically considering retirement. Yastrzemski credited Hriniak for the seven years of productivity added to his illustrious career. In 1979, upon reaching the twin thresholds of 400 home runs and 3,000 hits, Yastrzemski bought Hriniak a gold watch with the inscription:

To Walt. Thanks. I wouldn’t have made 400 or 3,000 without your help.

“I mean that from the bottom of my heart,” Yastrzemski said. “He helped me more than I can ever repay him for … throwing to me, helping me make adjustments in my stance. … I owe the man everything.”13 On September 13, 1979, Hriniak joined Yastrzemski and other guests in Washington when House Speaker Thomas “Tip” O’Neill saluted the slugger’s long career at a luncheon in the speaker’s Capitol office.

Dwight Evans proved another devotee. On July 4, 1980, the outfielder was struggling with a .189-5-22 batting line when he approached Hriniak for help. From July 1980 to August 1981, under the guidance of Hriniak’s patient, hitting-up-the-middle approach, Evans struck at a .310 pace with an on-base percentage over .400. In the strike-shortened 1981 campaign Evans joined Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, Jimmie Foxx, and Mickey Mantle as the only American Leaguers to lead the league in both walks and total bases in a season. That same season another adherent, newly acquired third baseman Carney Lansford, led the league in hitting while dramatically reducing his strikeout totals. Three years later Tony Armas credited Hriniak for a 50-point boost to his average during the outfielder’s Silver Slugger campaign. Throughout Hriniak’s 12-year tenure, the Red Sox led the major leagues in team batting average six times.

Despite this success, the atmosphere surrounding Red Sox nation was far from idyllic. On the heels of the 1986 American League championship farm director Ed Kenney Sr. announced his retirement (later retracted), upset over his perception of Hriniak’s meddling with the young hitters. The next year a country-club setting pervaded the clubhouse such that McNamara began contemplating banning golf clubs on road trips. The Red Sox finished in fifth place, largely due to the collapse of the pitching, but the finger-pointing did not stop there. Though the team’s offense increased in 1987 to .278 with 174 home runs, the downward spiral of Jim Rice and catcher Rich Gedman focused unwarranted attention on the team’s plate production in general and Hriniak in particular. A year later – after Boston rebound to division winner– Hriniak abruptly resigned from the Red Sox.

In October 1988 Hriniak signed a five-year, $500,000 contract with the Chicago White Sox, making him the highest paid coach in baseball.14 Chicago had managed one winning season since capturing the AL West Division flag in 1983 (when Hriniak’s mentor Charlie Lau was the hitting coach) and general manager Larry Himes saw in Hriniak an opportunity to improve upon “the worst [offense] in the American League since 1984.”15 Hired after Hriniak, manager Jeff Torborg had no say in the selection but that was of little concern to the new skipper. It was Hriniak whom Torborg had previously sought to assist his 21-year-old son Greg at Columbia University.16 That winter, under Hriniak’s guidance, many White Sox batters trekked to Boston to partake in what was dubbed the Larry Himes Scholarship Plan.

In February 1989 Harper Collins publishers issued A Hitting Clinic: The Walt Hriniak Way. Co-written with Henry Horenstein, Hriniak’s 120-page book offered the basic theories behind the Lau-Hriniak hitting-up-the-middle approach so familiar to their many disciples: Head down … “I start my swing by leading with my bottom hand and bring the bat on a downward plane to the ball.” Then follow through on the swing, finishing with hands high and one hand on the bat for increased speed.

“[Hriniak] refreshed my memory of what Charlie Lau taught. He put my swing right,”17 claimed Harold Baines during the left-handed hitter’s only Silver Slugger campaign. Even more remarkable was Hriniak’s work with catcher Ron Karkovice, whose average vaulted nearly 100 points over his 1988 output. Though the 1989 squad plummeted to a last-place finish, Chicago’s batting average increased from .244 to .271 as the White Sox scored 62 more runs than in 1988. Hriniak’s emphasis on line drives to all fields while cutting down on monster swings helped to push the White Sox into contention over the next five years – including a division title in 1993 and a first-place finish in the strike-shortened 1994 campaign. But underlying this success – the team’s best run since 1967 – lay marked turmoil. Himes was fired after the 1990 season. The rift that developed between Torborg, the 1990 AL Manager of the Year, and new general manager Ron Schueler contributed to Torborg’s departure a year later. Within months of Gene Lamont taking the managerial reins, reports emerged of a “growing sense that batting coach Walt Hriniak has worn out his welcome.”18

The negative reports centered largely on Hriniak’s handling of Frank Thomas. In 1992 the future Hall of Famer’s home run output dipped from 32 to 24 and, in the midst of Chicago’s disappointing third-place finish (and in a near-repeat of Hriniak’s 1987 Boston experience), fingers were pointed toward Hriniak. His line-drives-to-all-fields focus – conducive to the cavernous environs of Comiskey Park – drew unwarranted criticism. “[W]hat [Hriniak’s] doing to Thomas’ stroke, well, it’s almost criminal,” commented an opposing AL manager. “[R]ight now [singles hitter] Len Dykstra has more power than Thomas.”19 Remarkably, few scribes sought out Thomas’s opinion of the hitting coach as the right-handed slugger paced the league in doubles, walks, and on-base percentage.

Hriniak’s influence with the White Sox seemingly came to an end 31 games into the 1995 season. Terry Bevington had replaced Lamont and the relationship between the new manager and his hitting coach appeared to have been rocky from the outset – Bevington feeling Hriniak’s approach with the players was too hard-line, his style too old-school. Hriniak made it through the season and was fired in November, replaced by one of his Boston disciples, Bill Buckner. Hriniak retired to his native Massachusetts.

He settled northwest of Boston in Andover, Massachusetts, with his second wife,20 Woburn, Massachusetts, native Karen Cogen. He continued conducting individual hitting instruction and coached high-school ball with a close friend while occasionally finding time to play golf. In 1998 Hriniak beamed when Mark McGwire cited his adoption of the Lau-Hriniak approach as contributing to his record-setting home-run season. Two years later, Frank Thomas called.

In 1998-1999 Thomas experienced two consecutive sluggish campaigns. Markedly, of the 44 homers struck over the two-year period, only three were to the opposite field. Beginning in January 2000, Hriniak began working with Thomas from his Massachusetts residence. When Chicago’s spring camp opened a month later, the slugger flew Hriniak to the team’s Tucson, Arizona, base for continued instruction. The White Sox management was not pleased. They let the instruction continue only after all other players had left the practice fields and clubhouse. But the intense workouts with Hriniak paid off when Thomas reached single-season highs with 43 homers and 143 RBIs in 2000. This success spawned at least one additional winter in Massachusetts for Thomas, added instruction from Hriniak in Tucson and (when Thomas moved on to Toronto) Dunedin, Florida.

In 2004 the Natick High School alum’s name was added to the school’s Wall of Achievement. Six years later Hriniak was among the first group of inductees in the Natick Athletic Hall of Fame. Over the years further accolades came at Cooperstown when at Hall of Fame induction ceremonies in 1989, 2000, 2005, and 2014, Yastrzemski, Carlton Fisk, Wade Boggs, and Frank Thomas each cited Hriniak’s role in helping them gain admission to the shrine.

Hriniak ended his playing career with a scant 25 major-league base hits, nearly half (12) against Hall of Fame hurlers. But thousands more hits were credited to Hriniak as a coach. He was voted the best major-league hitting instructor in a players’ poll conducted by the Chicago Sun-Times at the 1990 All-Star Game. Though he attracted many critics throughout his long career – including Hall of Famers Ted Williams and Ralph Kiner – no one could argue with the Gas House Gang-intensity Walter John Hriniak brought to his craft.

Last revised: December 1, 2016

This article originally appeared in “The 1986 Boston Red Sox: There Was More Than Game Six” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Leslie Heaphy.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Walt and Karen Hriniak for their review and input to ensure the accuracy of the narrative. Further thanks are extended to SABR members Mark Aubrey, Bill Deane, and Alan Cohen for their diligent research, and Carl Riechers for editorial and fact-checking assistance.

Sources

Baseball-reference.com

articles.latimes.com/1990-08-08/sports/sp-280_1_white-sox

articles.sun-sentinel.com/1990-08-06/sports/9002070593_1_walt-hriniak-swing-holy-war

sabr.org/research/hearst-sandlot-classic-more-doorway-big-leagues

sabr.org/bioproj/person/6af260fc

sabr.org/bioproj/person/fbfdf45f

sabr.org/bioproj/person/feaf120c

02df676.netsolhost.com/wordpress/walter-hriniak-2010-member/

Walt Hriniak, telephone interviews, February 21 and April 7, 2015

Hriniak, Walt, with Henry Horenstein. A Hitting Clinic: The Walt Hriniak Way (New York: Harpercollins, 1989).

Pietrusza, David (editor). Baseball: A Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2000).

Notes

1 “Hriniak’s ‘Gashouse’ Style Pleases Salt Lake’s Zimmer,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1970, 41.

2 “Baby Braves Earn A-Plus Rankings in Pilot Birdie’s Book,” The Sporting News, November 8, 1961, 26.

3 “He was Natick’s ‘The Natural,’ now he’s in its Hall of Fame,” Boston Globe, May 2, 2010, 3.

4 “Garrett and Hriniak Shorten Swat Grip for Longer Wallops,” The Sporting News, July 22, 1967, 43.

5 “Pappas Seems Set as Brave … But Then Again,” The Sporting News, September 28, 1968, 16.

6 “Braves’ Brass Bursting With Optimism,” The Sporting News, January 4, 1969, 50.

7 “Hriniak’s ‘Gashouse’ Style.”

8 Don Zimmer, then the Expos’ third-base coach, likely played a role in recommending the signing.

9 Reunited in Denver three years later, Roenicke credited Hriniak for correcting flaws in his hitting approach.

10 “Rookie Leagues,” The Sporting News, August 7, 1976, 42.

11 “Dinner With Ted a Rare Treat,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1978, 62.

12 “No. 1 On The Hit Parade,” The Sporting News, May 13, 1985, 3.

13 “Fenway Fans Roar Big Tribute to Yaz,” The Sporting News, September 29, 1979, 14.

14 The Red Sox threatened to file tampering charges against Chicago but nothing came of this.

15 “A.L. West – White Sox,” The Sporting News, November 7, 1988, 55.

16 Throughout his career Hriniak assisted many opposing players, including fellow New Englander Steve Lombardozzi, Cleveland outfielder Cory Snyder, Detroit’s Tony Phillips, and Milwaukee’s Rob Deer.

17 “A.L. West – White Sox,” The Sporting News, August 14, 1989, 23.

18 “Can the White Sox save an unraveling season?” The Sporting News, August 10, 1992, 27. The circus-like atmosphere was further exacerbated in 1994 when Hriniak was assigned to work with Michael Jordan during the basketball great’s brief foray in baseball.

19 “Caught On The Fly,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1991, 3.

20 They married in 1990. A 1975 marriage to Patricia Ann Doherty had ended in divorce. The earlier union produced one child. This child – daughter Jill – provided Hriniak with two grandchildren.

Full Name

Walter John Hriniak

Born

May 22, 1943 at Natick, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.