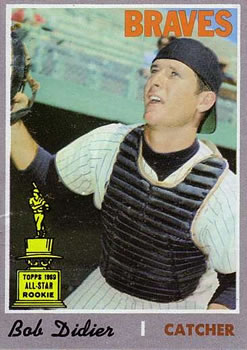

Bob Didier

Son of a great baseball man, scout and executive Mel Didier, Bob Didier has been in the game for more than five decades, almost as long as his father. He was a professional catcher from 1967 through 1976, including one full season and parts of five others in the majors. He has since served as a manager, coach, and scout in various organizations — winning five World Series rings.

Son of a great baseball man, scout and executive Mel Didier, Bob Didier has been in the game for more than five decades, almost as long as his father. He was a professional catcher from 1967 through 1976, including one full season and parts of five others in the majors. He has since served as a manager, coach, and scout in various organizations — winning five World Series rings.

The Didier baseball legacy is tangible in various ways, but one is especially enjoyable. Mel was renowned as a storyteller; Bob also has that gift and takes relish in recounting his experiences.

Robert Daniel Didier was born on February 16, 1949, in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. He was the second of four children born to Melvin and Mary Ellen Didier. Mary Ellen’s maiden name, Daniel, became Bob’s middle name. He was called Robert in honor of his paternal grandfather and uncle. His siblings were Melvin Jr. (“Skip”), Cindee, and Lori.

Mary Ellen Didier was born in Jackson, Mississippi, but went to high school in Baton Rouge and then to Louisiana State University, where she met and married Mel. After raising her children, she went to work in the East Baton Rouge Parish Assessor’s Office.1

When Bob was born, his father was in Hattiesburg because he was continuing his undergraduate studies at Mississippi Southern College (now the University of Southern Mississippi). A shoulder injury just a few months later signaled the end of Mel Didier’s minor-league pitching career. After Mel got his degree, he returned with his family to Louisiana. He coached baseball and football and taught history at Catholic High in Baton Rouge, Opelousas High (in the seat of St. Landry Parish, about half an hour north of Lafayette), and Glen Oaks High (in East Baton Rouge Parish).

As an infant, Bob Didier received a nickname that stuck throughout his life. Friends and relatives cooed over him and said “Hiya” so often that Mel Jr., who was only about a year and a half older, thought “Hiya” was his baby brother’s name.2 Not only people from his early years but also big-league buddies such as Dusty Baker and Bill Buckner still use it.

Young Bob always had a deep desire to play baseball, and his father encouraged him. His grandfather was a semipro catcher who was talented enough to attract attention from a New York Yankees scout, and all five of his uncles played as well (two in semipro ball and three in the minors).3 Bob received his first catcher’s mitt at the age of three from his father. Mel later said he figured that catching was the fastest way to the big leagues.4

When Bob was four or five years old, Mel Didier became a major-league baseball scout in addition to his school duties. John McHale took over as the director of minor-league operations for the Detroit Tigers after the 1953 season and gave Mel his first scouting job. They’d known each other since 1948, when Mel got his first professional contract from McHale, whose long executive career started as the Tigers’ assistant farm director. McHale became general manager of the Milwaukee Braves in 1959, and Mel followed, remaining with the franchise after it moved to Atlanta for the 1966 season.5

As a boy, Bob Didier’s favorite team was the New York Yankees, who made an impression on him (and many others) because of all the pennants and World Series they were winning in that era. His favorite player was their perennial All-Star catcher, Yogi Berra.6

As a result of his father’s work-related moves, Bob Didier played Little League ball in Opelousas but went to Glen Oaks High. As a junior and senior there, he attended baseball clinics in Baton Rouge. His catching instructors included Tim McCarver, Bob Tillman (later a teammate), and Jerry Grote.7 Mel Didier was responsible for staging these clinics, along with local scouts Tony John, Walker Cress, and John Fetzer. Attendance grew to 500 boys, making it the largest such program in the country.8

In Bob Didier’s junior year, 1966, Glen Oaks won the state baseball championship in Class 3A, then the top level in the Louisiana High School Athletic Association. At Glen Oaks, Bob was also an all-district basketball player and a star quarterback on the football team. According to his father, he had 35 or 40 offers to play college football. Bear Bryant, the legendary head coach at the University of Alabama, was a good friend of Mel Didier’s. Bryant was one of the coaches interested in Bob, who wasn’t fast but could throw on the move and run the option.9

The young man had a hard choice, but “I told Hiya to make up his own mind,” said Mel, looking back in early 1969.10 A couple of months later, Bob echoed him, saying, “He always said to do what I thought best.” Football was the bigger sport in Louisiana, but when it came down to it, Bob always enjoyed playing baseball more.11

Thus, he signed with Atlanta after the Braves selected him in the fourth round of the amateur draft in June 1967. It’s noteworthy that his father was not involved. John McHale wondered why Mel was filing reports on many fine Louisiana prospects except for Bob. Mel told McHale what he’d told Jim Fanning, the Braves’ assistant GM: that he would not report on his own son. He viewed it as nepotism and against his old-school beliefs. Therefore, Fanning and Ray Hayworth, the team’s director of scouting — catchers themselves in their playing days — went to see Bob play in Baton Rouge.12

The 18-year-old Didier spent his first summer of pro baseball at Kinston in the Carolina League and West Palm Beach in the Florida State League. His hitting was light (.176-0-6 in 51 games). However, Mel Didier had insisted on one proviso in his son’s contract: that Bob had to go to spring training with the big club for two years.13 The first of those camps was in 1968. Bob Uecker, then a Braves catcher, later said, “He stood apart from the others then. You knew he was something special. I knew then that I was probably going to retire early.”14 Indeed, Uecker’s playing career ended that April.

Another anecdote from that camp revolved around Frank Ryan, player representative for bat manufacturer Hillerich & Bradsby. Didier got his first big-league bat contract that spring. Yet Ryan remembered him from his junior year at Glen Oaks, when Mel Didier had wangled a shipment of six Louisville Sluggers stamped “Hiya Didier.” It was just what came out of Mel’s mouth when Ryan asked about the branding. The “weird name” stuck in Ryan’s mind, and he was so tickled that he insisted that it be used again. “I carried those bats and fungo sticks with me for 20 or 30 years,” Bob recalled.15

Didier remained at Class A in 1968, but with Greenwood (South Carolina) in the Western Carolinas League. He helped his teammate and friend Dusty Baker in situations that were not comfortable for African-Americans.16 His hitting picked up to .243-1-28 in 82 games, and the increase came even though he started switch-hitting that year, and despite missing six weeks after having his appendix removed.17

That fall, the Braves sent Didier to the Instructional League in Arizona, where he made a strong impression on manager Lum Harris.18 At that time, Louisiana native Clint Courtney was a roving minor-league catching instructor for the Braves. Noted for his rigorous catching drills, Courtney helped Didier at the plate in particular, encouraging him to be more aggressive (a trait for which “Scrap Iron” was known as a player).19 “You talk about a character!” said Didier, whose path later crossed with Courtney’s in Mexican winter ball.20

During spring training in 1969, the Braves shared facilities in West Palm Beach with the Montreal Expos, one of the National League’s two new expansion teams. John McHale had become the Expos’ president and chief executive officer, and had hired Mel Didier that January as scouting director. This was an issue because Lum Harris and Expos manager Gene Mauch had instructed their players not to fraternize with the other team.

“Hiya and I know the rules,” said Mel, “but you can see we bend them a little. I stay away from the Braves clubhouse and Hiya stays away from the Expos facilities.” Father and son were in the same motel, and they saw each other in the lobby. Mel confessed to buying Bob lunch on a few occasions, but foresaw the real problem as Mary Ellen’s arrival. “She just might not understand why a mother can’t fraternize with her son.”21

Bob Didier vaulted into the majors that spring. According to Mel, Paul Richards (who had joined the Braves’ front office in 1966), saw himself in Bob: a catcher who couldn’t hit much but could throw. Didier showed off his arm but also hit surprisingly well. Richards traded Atlanta’s primary catcher, Joe Torre, in March amid a contract dispute. That gave backup Bob Tillman the idea that he had leverage in negotiating; he said that he would go work as a banker in Tennessee unless he got a certain amount of money. Richards let Tillman walk. When Walt Hriniak broke a bone in his right thumb, 20-year-old Didier was left as the first-string catcher.22

This was a daunting task for any receiver because the Braves then had knuckleballer Phil Niekro on their staff. But Richards gave Didier some valuable lessons and found him to be an apt pupil. “He talked to me a lot about catching the knuckleball,” said Didier. “He said, ‘Let the ball come to you, don’t reach for it.’ He really kept to himself, didn’t hardly talk to anybody — he had that air about him. But when he did talk to you, it was, ‘Wow!’ A very smart person.”23

Tillman returned to the Braves and was their catcher on Opening Day. However, Didier made his first start the next night and got his first base hit, a ground single into right field off Gaylord Perry. He joked, “I’m surprised it went through. That [first baseman Willie] McCovey’s so big that when he dives, he reaches all the way to second base.”24

The St. Louis Cardinals faced the Braves first that year on May 26. Tim McCarver remembered Didier from the Baton Rouge clinics several years before and greeted him warmly. He introduced the rookie around, and Lou Brock also knew who Bob was because Mel Didier had tried to land Brock for the Braves. But then Hiya asked about meeting Bob Gibson, who was notorious as a hardcore competitor. He likened the response to the old commercials for the stockbroking firm E.F. Hutton. “Everybody turned and stopped talking. Then they said, ‘You don’t want to meet him!’”25

Didier became the main man behind the plate for Atlanta in 1969, playing in 114 games and starting 108 of them. Phil Niekro had his first 20-win season, and Didier deserved a good deal of credit. According to Niekro, he wasn’t afraid to call for the knuckler with a full count and a man on third. Richards proclaimed that with all due respect to Rick Ferrell, nobody had ever done a better job catching the butterfly than Didier.26 The Braves added another knuckleballer, Hoyt Wilhelm, that September. Wilhelm was more than twice as old as Didier and older even than father Mel, which prompted various jokes.

With all those knucklers, Didier had a league-leading 27 passed balls. Niekro also threw 16 wild pitches that year. Didier later joked that he got to know everybody in the first two rows behind home plate by their first name. His approach to receiving the knuckleball was to try blocking it like a ball in the dirt. If he didn’t catch it with his oversized catcher’s mitt, it hit off his body and he kept it in front of him.27

Aside from passed balls and wild pitches, however, Didier committed just four errors. He hit .256 in 352 at-bats, driving in 32 runs (he never did hit a home run in The Show). One of his favorite memories came from a game at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium on August 16, when he doubled off Bob Gibson. As he reached second base, Gibson turned and gave him one of his fierce stares…even though the Cardinals were leading 8-0 in the eighth inning. “I didn’t want to meet his eyes,” said Didier.28

Didier’s overall showing led Lum Harris and teammates to talk him up as a Rookie of the Year candidate that summer.29 He wound up tied for fourth, getting two of the 24 votes from the Baseball Writers’ Association of America.

The Braves won the division title in the National League West that year, which gave Didier his only post-season action. The Amazin’ Mets swept Atlanta in three games, but Didier played every inning except the last. Though he was 0-for-11 at the plate, he managed not to strike out against young flamethrower Nolan Ryan. He talked about how batters felt facing Ryan in those days. “This guy threw so hard — five to eight miles per hour faster than anyone I ever faced, it must have been 104. But he didn’t know where it was going. He’d strike out 12, walk six or seven, hit a few, throw 200 pitches. Guys would be begging out of the lineup, saying, ‘my leg is tight’ or ‘my ribs hurt.’ They didn’t want to get killed!”30

Didier also had amusing memories of one of his star teammates in Atlanta, Rico Carty. “Rico liked flashy clothes. Green suits, yellow suits, white suits. If he liked shoes, he’d buy five pairs. Green alligator shoes. But one time we were on a plane, and the guys noticed that he was wearing two right shoes. Rico got mad because he thought that people were laughing at him. Well, they kinda were!

“At the end of one season, I was in the locker room and he was boxing up some stuff. I saw one of my mitts and a pair of my shoes going into the box. I asked him what was up, and he said he was bringing things home for kids in the Dominican Republic. I said, ‘Hey man, you could’ve asked!’”

There was bad blood between Carty and Atlanta’s biggest star, Hank Aaron. “Rico believed in voodoo. He had a voodoo doll of Aaron with needles stuck in him!”31

Not long after his rookie year ended, on October 20, Didier married his high-school sweetheart, Kitty Thompson. After honeymooning in Hawaii, he spent the winter hunting and watching “Pistol Pete” Maravich, the basketball superstar then at Louisiana State University.32

Expectations were high that Didier would improve on his rookie showing.33 However, he never played another full season in the majors. In 1970, Atlanta sent him down to Triple-A Richmond in mid-July after acquiring pitcher Don Cardwell. A cold bat was the main reason: Didier was hitting just .151 when he was sent down. Bob Tillman, in his final big-league season, got the biggest share of the catching duties, and Hal King (drafted from the Red Sox organization that winter) was hitting well.34

Didier returned to Atlanta when the rosters expanded in September and started 14 games that month, but he ended the season at just .149. He admitted to losing confidence, yet said that he didn’t want to be pigeonholed as simply a knuckleball catcher.35

During the offseason, Didier enjoyed hunting again, including some time with Hoyt Wilhelm in southern Georgia. “We walked for miles and miles,” he said. “I kept saying to myself, ‘I can’t let this old man outwalk me.”36

Slugger Earl Williams emerged as NL Rookie of the Year in 1971, although he played a lot at first and third base in addition to catching. King was the main backup, and Didier was third string. Again his defense was fine, but his bat was quiet (.219-0-5). He was sent down to Richmond in July, which led him to call for a trade.37 He got into just two games after being recalled again in September.

Atlanta traded King in December 1971 but received Paul Casanova, a superb defensive catcher with some power. Didier spent the bulk of the 1972 season at Richmond. The rigors of his position were evident in a broken nose, suffered in a home-plate collision with Junior Kennedy on June 25. The Rochester shortstop was still standing up.38 The doctor who examined Didier a couple of days later issued dubious advice: it was okay to play, but not to blow his nose or sneeze for at least 10 days.39

Didier returned to Atlanta once more in September, hitting .300 in 13 games, which were his last with the Braves. After the season ended, he won the Rawlings Silver Glove for outstanding fielding in the minor leagues.

Looking back on his time in Atlanta, Didier expressed awe at Hank Aaron’s toughness and ability. In his late 30s, Aaron’s knees were troublesome. “I remember having my little finger taped and Hank was having capsules of fluid drained out of his knee. You wouldn’t expect him to play at all. But he’d still go out there, without any practice, and just kill the ball.”40

Atlanta sent Earl Williams, who never really embraced the catching job, to Baltimore in a six-player trade after the 1972 season. One of the players they got back was catcher Johnny Oates. Casanova retained his backup job, and toward the end of spring training in 1973, Atlanta also acquired Dick Dietz.

Didier went back to Richmond to start the season, and he was upset. But a change of scenery came at last that May through a trade to the Tigers for another catcher, Gene Lamont. Detroit viewed Didier as insurance at the position and assigned him to Toledo, also in the International League.41 He thought he was capable of more and wanted to show that he could be at least a number-two catcher or even a starter.42 As it turned out, he got into seven games for the Tigers in September, going 10-for-22 (.455).

Didier won his second straight Silver Glove that December.43 The news came out while he was playing in the Dominican league with Águilas Cibaeñas. “They approached me about coming down while I was in Toledo. I did well and made a little money. Rico Carty was there. Julián Javier was still playing. Bill Madlock was on the team too. So was Dave Parker.”44

Following that season, in February, Didier took part in the Caribbean Series. He joined the Licey Tigres, who had won the Dominican championship that winter and thus advanced to the round robin tournament against the region’s other winter-ball champs.45 Licey, managed by future Dodgers skipper Tommy Lasorda, featured many Los Angeles players, including veteran local heroes (Manny Mota) and younger Americans (Bill Buckner, Steve Garvey, and Charlie Hough). Didier was needed because Steve Yeager gotten hurt in a collision at home plate with massive Dave Parker.

Didier got into three of the six games in the Caribbean Series.46 Yet he remembered it mainly because he too got hurt. “I’d made about $2,500 a month that winter, and they offered me another $2,500 for the extra week. I said no at first because I was tired. They bumped it up to $3,500 and I started to stutter. Then they made it $4,000 and I took it. I chased a foul pop and jammed my ankle on the backstop. It was all swollen up. When I got home, my dad took me to see the trainer at LSU, who said it would take four to six weeks to get better.”47

Yet Didier had to gut it out because the Tigers’ catching situation was crowded. Veteran Bill Freehan was still with the club, which reacquired Gene Lamont in December 1973. Then in March 1974, Jerry Moses came in a three-way deal with the Cleveland Indians and the Yankees. Detroit sold Didier’s contract to the Boston Red Sox later that month.

Boston’s star catcher, Carlton Fisk, was not ready for Opening Day 1974 after taking a foul tip to the groin in spring training. Didier thus backed up Bob Montgomery, who caught every inning of the team’s first 10 games. Didier then made five consecutive starts from April 19 through April 23. Still hampered by his ankle injury, he was 1-for-14 (.071). The Red Sox sent him back down to Triple-A Pawtucket once Fisk returned. Those were Didier’s last games in the majors.

Boston traded Didier to the Houston Astros in exchange for Roe Skidmore in December 1974. When the deal took place, the catcher was playing winter ball again, this time in the Mexican Pacific League. A month before, he’d gotten a call from Clint Courtney at 5 A.M. asking what he was doing. “Sleeping,” said Didier, but he took the offer to join the Guaymas Ostioneros, who’d asked Courtney to manage after firing Miguel “Pilo” Gaspar.48

Didier told various choice stories about Courtney. “Scrap Iron” said that the team needed some speed at the top of the lineup, so Didier asked his father if he knew of anybody in the Expos system. Mel sent Jerry White down to Guaymas. Bob warned White that Courtney might use racist terms but that he was good-hearted. Sure enough, Scraps had not been expecting a black man and said as much, with the n-word. Yet White turned out to be Courtney’s favorite player on the team, by playing well and winning the skipper money in bets on pregame sprinting contests.

Courtney was known for bathing seldom and the resulting ripe body odor. Didier remembered that one time he was sitting in the back of the team bus when Scraps invited him to sit by his side. He dreaded the prospect because Courtney was wearing a pair of white plastic boots with no socks. Sure enough, Scraps took off the boots, and the stink about flattened Didier.

Courtney was also known for his love of hunting, which Didier shared. Dove hunting in particular was a favorite, and the two men had a sporting bet on who could bag more with one box of shells. Courtney won by using visiting scout Al LaMacchia, who wasn’t a country boy and knew nothing about hunting, as a human bird dog. LaMacchia enjoyed telling the tale against himself over the years.49

Didier spent all of the 1975 season with Iowa in the American Association, going .251-3-39 in 109 games as the primary catcher for the Oaks.50 He became a free agent, and Atlanta gave him a non-roster invitation to spring training in 1976.51 He wound up back in Richmond as one of five catchers the team used that year. All of the others were big-leaguers as well: Don Werner, Pete Varney, Joe Nolan, and young prospect Dale Murphy. Didier also served as a coach for the R-Braves and hit .237-1-16 in 47 games.

At age 28 in 1977, the extended second phase of Didier’s baseball career then began. He felt that he was spinning his wheels as a player, and that it was a good time to start managing, something he’d long wanted to do.52 He got encouragement from Jack McKeon, who’d managed Richmond in 1976 (though he couldn’t stand McKeon’s cigars). He also benefited from the pitching knowledge he’d gained from coach Johnny Sain.53

Didier has since compiled the following résumé:

|

Year |

Organization |

Role(s) |

|

1977 |

Atlanta Braves |

Manager, Kingsport Braves (Appalachian League, rookie ball) |

|

1978 |

Seattle Mariners |

Manager, Bellingham Mariners (Northwest League, short-season Class A) |

|

1979 |

Seattle |

Manager, San José Missions (California League, Class A) |

|

1979-80 (winter) |

Ciudad Obregón Yaquis (Mexico) |

Manager |

|

1980 |

Milwaukee Brewers |

Manager, Vancouver Canadians (Pacific Coast League, Class AAA) |

|

1981-82 |

Oakland A’s |

Manager, West Haven A’s (Eastern League, Class AA) |

|

1981-82 (winter) |

Mazatlán Venados (Mexico) |

Manager (1 of 3) |

|

1981-82 (winter) |

Tigres de Aragua (Venezuela) |

Coach |

|

1983 |

Oakland |

Manager, Tacoma Tigers (Pacific Coast League) |

|

1983-87 (winters) |

Tigres de Aragua |

Manager (three seasons, excluding 1985-86) |

|

1984-86 |

Oakland |

Major-league coach (third base and bench) |

|

1987-88 |

Houston Astros |

Manager, Tucson Toros (Pacific Coast League) |

|

1989-90 |

Seattle |

Major-league third base coach (1989) and bullpen coach (1990) |

|

1991-92 |

Toronto Blue Jays |

Roving minor-league catching instructor |

|

1993-95 |

Toronto |

Manager, Syracuse Chiefs (International League, Class AAA) |

|

1995 |

Toronto |

Manager of Toronto’s replacement team |

|

1996 |

Toronto |

Roving minor-league catching instructor |

|

1997-2001 |

New York Yankees |

Advance scout; doubled as major-league catching coach (2000) |

|

2002 |

Montreal Expos |

Manager, Brevard County Manatees (Florida State League, Class A) |

|

2003-05 |

Chicago Cubs |

Advance scout. The Cubs were then managed by old friend Dusty Baker. |

|

2006-07 |

Arizona Diamondbacks |

Minor-league catching coordinator and advance scout |

|

2008-10 |

Arizona |

Manager, Yakima Bears (Northwest League) |

|

2011 |

Brockton Rox (Can-Am League) |

Hitting instructor. The Rox were managed by Bill Buckner. |

|

2012-13 |

Temporary semi-retirement |

|

|

2014 |

Washington Wild Things (Frontier League) |

Hitting coach |

|

2015- |

Major League Baseball |

Roving youth instructor |

One notable story from Didier’s early days as a manager came while working under his father. Mel Didier became director of the Mariners’ minor league system and scouting in 1976 but was dismissed in September 1978. An incident involving the M’s Bellingham farm team led indirectly to his departure. Bob reported that some young men on his club were so desperate for food that they had shoplifted some bread. They were ill-paid enough as it was, but Seattle was deducting workers’ comp payments and was too cheap to cover them (unlike other franchises). Mel went on a tirade against Kip Horsburgh, the Mariners’ bean-counting executive director, and lost his job after another subsequent clash.54

As a skipper, Bob showed that he had a little Earl Weaver and/or Billy Martin in him. At Vancouver in 1980, he was ejected on May 31, and showered the field with bats, batting helmets, jackets, and whatever else was loose in the dugout. The very next day, he got the heave-ho again and cursed audibly. The league president gave him a three-day suspension and $300 fine.55

Oakland dismissed Martin as manager after the 1982 season, and Didier was interviewed as a potential replacement. He remembered that he had the backing of Dick Wiencek, the club’s director of minor-league personnel, but at that time his lack of big-league coaching experience was a strike against him.56 The closest he got to managing in the majors was as skipper of Toronto’s replacement team in the spring of 1995, while the major-league strike was still in effect.

While he was coaching with the A’s, Didier got married for the second time, to Nancy Bradford. They had two children, Kayce and Beau. From his previous marriage, Didier had three children. All of them also bore the initials R.D.: Robyn Danielle, Rani Denise, and Robert Daniel Jr. (who chose to go by his middle name). Beau, who represented the fourth generation of ballplaying Didiers, was good enough that the Pittsburgh Pirates made him a 40th-round draft pick in 2008. He decided to go to LSU, though, and his playing days ended after college ball.

During his time in the Oakland organization, Didier also managed for three winters in Venezuela. His club, Tigres de Aragua, featured two of the biggest local names: shortstop Dave Concepción and outfielder Vic Davalillo, who by then was in his 40s. Davalillo also had a longstanding reputation as a drinker, and he indulged himself even more in winter ball. Didier recalled that after one hard night, it didn’t look as if Vic could play. “But we put him on the bench anyway, figuring that maybe he’d be able to pinch-hit.” Sure enough, a situation arose, and Didier sent the wiry little veteran up. “His cleats weren’t even laced up, they were wide open. A pitch came in, and he went into that leg kick he had and fell on his backside. But then he got up and hit one over the shortstop for a two-run single!”57

Didier got his first two World Series rings with the Blue Jays organization when Toronto won it all in 1992 and 1993. The other three came with his boyhood favorites, the Yankees, in three straight years from 1998 through 2000. There might have been a fourth, but the Arizona Diamondbacks — a team his father had helped construct — upset New York in 2001.

When asked for George Steinbrenner stories, Didier replied, “I’d need a book” but offered a couple of favorites. The first dated from spring training 1999. Derek Jeter and Mariano Rivera had just won arbitration cases against the Yankees, and Steinbrenner’s furious response to losing was to send the advance scouts (including Didier) home. Didier wore a beeper in those days, and it went off for the first time in ages. It turned out to be Yankees manager Joe Torre; when they spoke, Torre laughed and said, “Go home, you’ll be paid.” Meanwhile, Mel Didier paid a visit to Legends Field in Tampa. Steinbrenner entered the room where Mel was seated and busied himself wiping down the counter around a coffee station. He spotted Mel and said, “I thought I sent you home!” When Mel explained who he was, the mercurial Steinbrenner exclaimed, “Your son is the best scout we’ve got!”

The other story concerned a playoff loss at Seattle (probably Game Five of the AL Championship Series in 2000). As the teams went to the airport to fly back to New York, The Boss was in a foul mood and cursing. Three buses full of players, front office people, and wives pulled up. Steinbrenner ordered the “civilians” not to board, saying, “I want my warriors to go first!” Though the Yankees had a much bigger aircraft than the Mariners, Steinbrenner went up to the pilot and said, “If our plane doesn’t beat their plane, I’ll get you fired!”

Both anecdotes underscore how Steinbrenner and Donald Trump have often been compared. Indeed, Didier remembered seeing the future 45th U.S. President riding in the private elevator at Yankee Stadium.58

Didier called Joe Torre “a great boss, really easy to work for.” Torre had always been nice to him, dating back to spring training 1968. Didier noted the manager’s ability to defuse tense situations and summed it up by saying, “Joe made my time with the Yankees cool.”59

As may be expected, Didier learned lessons from his father in scouting and player development. One was to be organized, but the most important was “don’t overcoach great talent.” Another story emphasizing this point came from his time with the Blue Jays, when Shawn Green was a prospect. “He had the prettiest natural swing, and Mel Queen [then Toronto’s farm director] said, ‘If I see any of you guys mess with his swing, you’re fired.’”60

Since 2015, Didier has run camps and worked at academies for Major League Baseball. Many of these focus on helping minority kids, and Didier has worked with African-American catchers Charles Johnson and Lenny Webster as a catching instructor. He’s traveled abroad (to Brazil and Italy, for example) and has become friends with other vets such as Barry Larkin, Lee Smith, and John Cangelosi.

Approaching age 70, Bob Didier was in good health and hoped to remain in his instructor role indefinitely. Baseball is what he knows and he enjoys teaching it and being around friends. “As long as I can stand up and communicate to the kids,” he said, “I’ll keep doing what I’m doing.”61

Last revised: June 20, 2018

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Bob Didier for his memories (telephone interviews, May 31 and June 5, 2018). Continued thanks to Jesús Alberto Rubio, Eduardo Almada, Alfonso Araujo, and Guillermo Gastélum for help with the history of Mexican winter ball.

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Other sources

Carlos Cárdenas Lares, Guía del Fanático ’93, Caracas, Venezuela: Fondo Editorial Cárdenas Lares, 1993.

Notes

1 “Mary Ellen Didier,” The Acadiana Advocate (Lafayette, Louisiana), March 31, 2016. Telephone interview, Bob Didier with Rory Costello, May 31, 2018 (hereafter Bob Didier interview #1).

2 Bob Didier interview #1.

3 Mel Didier and T.R. Sullivan, Podnuh — Let Me Tell You a Story, Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Gulf South Books, 2007, 58. Richard Cuicchi, “Mel Didier’s passing recalls prominence of his Louisiana baseball family,” Crescent City Sports, September 12, 2017.

4 Wayne Minshew, “Even Niekro’s Knuckler Can’t Dim Didier’s Dream,” The Sporting News, September 20, 1969, 21.

5 Shi Davidi, “Longtime Blue Jays scout Mel Didier dead at 91,” Sportsnet.ca, September 11, 2017.

6 Becca Gladden, “Interview with Bob Didier, Former Major League Baseball Catcher,” Careerthoughts.com, January 15, 2011 (https://careerthoughts.com/bob-didier/)

7 Minshew, “Even Niekro’s Knuckler Can’t Dim Didier’s Dream.”

8 Bob Didier interview #1.

9 Didier and Sullivan, Podnuh, 58.

10 Ed Plaisted, “Father, Son on Opposite Sides,” Palm Beach Post, February 23, 1969, 57.

11 Wayne Minshew, “Braves’ Didier: A Dream Come True,” The Sporting News, April 26, 1969, 22.

12 Didier and Sullivan, Podnuh, 57-58. Telephone interview, Elena Didier with Rory Costello, April 20, 2018.

13 Didier and Sullivan, Podnuh, 58.

14 Wayne Minshew, “New [Minnie] Minoso? Braves’ Ralph Garr Hustles Just the Way Minnie did,” The Sporting News, February 17, 1968, 30. Wayne Minshew, “Didier Already a Prize Catcher, and He’s Sure to Improve Too,” The Sporting News, January 3, 1970, 45.

15 Telephone interview, Bob Didier with Rory Costello, June 5, 2018 (hereafter Bob Didier interview #2).

16 Didier and Sullivan, Podnuh, 58.

17 Minshew, “Even Niekro’s Knuckler Can’t Dim Didier’s Dream.” Frank Eck, “Young A-Braves Catcher Knew How to Be Known,” Associated Press, May 29, 1969.

18 Wayne Minshew, “Speedster Garr Delights Braves with Sharp Play,” The Sporting News, December 7, 1968, 37.

19 Eck, “Young A-Braves Catcher Knew How to Be Known.” “Atlanta’s Didier — Veteran at 21,” Palm Beach Post, February 26, 1970, 39.

20 Bob Didier interview #1.

21 Plaisted, “Father, Son on Opposite Sides.”

22 Didier and Sullivan, Podnuh, 58-59. Wayne Minshew, “Hriniak, Didier Duel for Tepee Job Behind Dish,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1969, 13.

23 Bob Didier interview #2.

24 Minshew, “Braves’ Didier: A Dream Come True.”

25 Bob Didier interview #2. Note: the Braves and Cardinals did not meet in exhibition season in 1969.

26 Roy Blount Jr., “Atlanta Tranquillity Base here,” Sports Illustrated, August 4, 1969.

27 Glen Farley, “Rox coach Didier not one to knuckle under pressure,” Patriot Ledger (Quincy, Massachusetts), May 18, 2011

28 Bob Didier interview #1.

29 Wayne Minshew, “Didier Rates Trophy; He Can Handle Niekro Knuckler,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1969, 13.

30 Bob Didier interview #2.

31 Ibid.

32 Wayne Minshew, “Braves Can Hardly Wait for Long Look at Hurler [Mike] McQueen,” The Sporting News, November 8, 1969, 38. “Atlanta,” The Sporting News, January 3, 1970, 6. “Atlanta,” The Sporting News, February 28, 1970, 6.

33 Minshew, “Didier Already a Prize Catcher, and He’s Sure to Improve Too.”

34 Wayne Minshew, “Braves, in Surprise Move, Delegate Didier to Minors,” The Sporting News, July 25, 1970, 14.

35 Wayne Minshew, “Long Winter for Didier, Trying Comeback at 21,” The Sporting News, November 28, 1970, 49.

36 Ira Berkow, “Wilhelm Retire? Someday, Maybe…”, Newspaper Enterprise Association, syndicated feature, first published June 8, 1971.

37 Wayne Minshew, “Niekro’s Floater Teases Batters,” The Sporting News, August 28, 1971, 20.

38 “Sisler Frets, Sees His ‘Dream Race’ Faltering,” The Sporting News, July 15, 1972, 37.

39 “Int. Items,” The Sporting News, July 29, 1972, 48.

40 Bob Didier interview #2.

41 Jim Hawkins, “Tigers Finally Land Backup Catcher — Didier,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1973, 24.

42 “Didier Seeking Chance to Wake Somebody Up,” The Sporting News, July 29, 1973, 47.

43 Larry Wigge, “Catcher Bob Didier Gets His Second Silver Glove,” The Sporting News, December 15, 1973, 47.

44 Bob Didier interview #2.

45 Venezuela did not participate in this edition of the Caribbean Series because of a players’ strike. Instead, there were two teams from the host nation, Mexico.

46 Alfonso Araujo Bojórquez, Series del Caribe: Narraciones y Estadísticas, 1949-2001, Culiacán, Sinaloa, Mexico: Colegio de Bachilleres del Estado de Sinaloa, 2002, 41.

47 Bob Didier interview #2.

48 The Oystermen were 9-22 under Gaspar but Courtney (who’d played for and managed Guaymas at age 22 in the 1949-50 season) turned the club around, going 27-23.

49 Ibid.

50 Skidmore wound up in Iowa that year too. He was unhappy as a benchwarmer in Pawtucket and used his connections to swing a deal to the Oaks.

51 Wayne Minshew, “Brimming with Talent: Braves’ Rookie [Jerry] Royster,” The Sporting News, March 13, 1976, 38.

52 Bill Lane, “Local Braves’ Strengths: Line-Drive Hitting, Pitching,” Kingsport (Tennessee) News, June 21, 1977, 4.

53 Bob Didier interview #1.

54 Didier and Sullivan, Podnuh, 107-108.

55 “Didier Fined and Suspended,” The Sporting News, June 28, 1980, 39.

56 Bob Didier interview #1. Kit Stier, “Brain Trust Added to Oakland ‘Family,’” The Sporting News, November 8, 1982, 33.

57 Bob Didier interview #2. A nearly identical story about Davalillo comes from his time with the Cardinals in the early ‘70s.

58 Bob Didier interview #1.

59 Ibid.

60 Ibid.

61 Ibid.

Full Name

Robert Daniel Didier

Born

February 16, 1949 at Hattiesburg, MS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.