Washington Senators I team ownership history

This article was written by Andrew Sharp

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

The Washington Senators played at Griffith Stadium from 1911 to 1960 before leaving for Minnesota. The expansion Senators played one year there in 1961 before moving across town to D.C. Stadium, later called Robert F. Kennedy Stadium. (Library of Congress, Horydczak Collection)

When the National League dropped four cities, including Washington, after the 1899 season, an opening was left for the upstart American League. What remained of the Kansas City team from the Western League was moved to Washington, where the Senators became an original member of the AL in 1901.

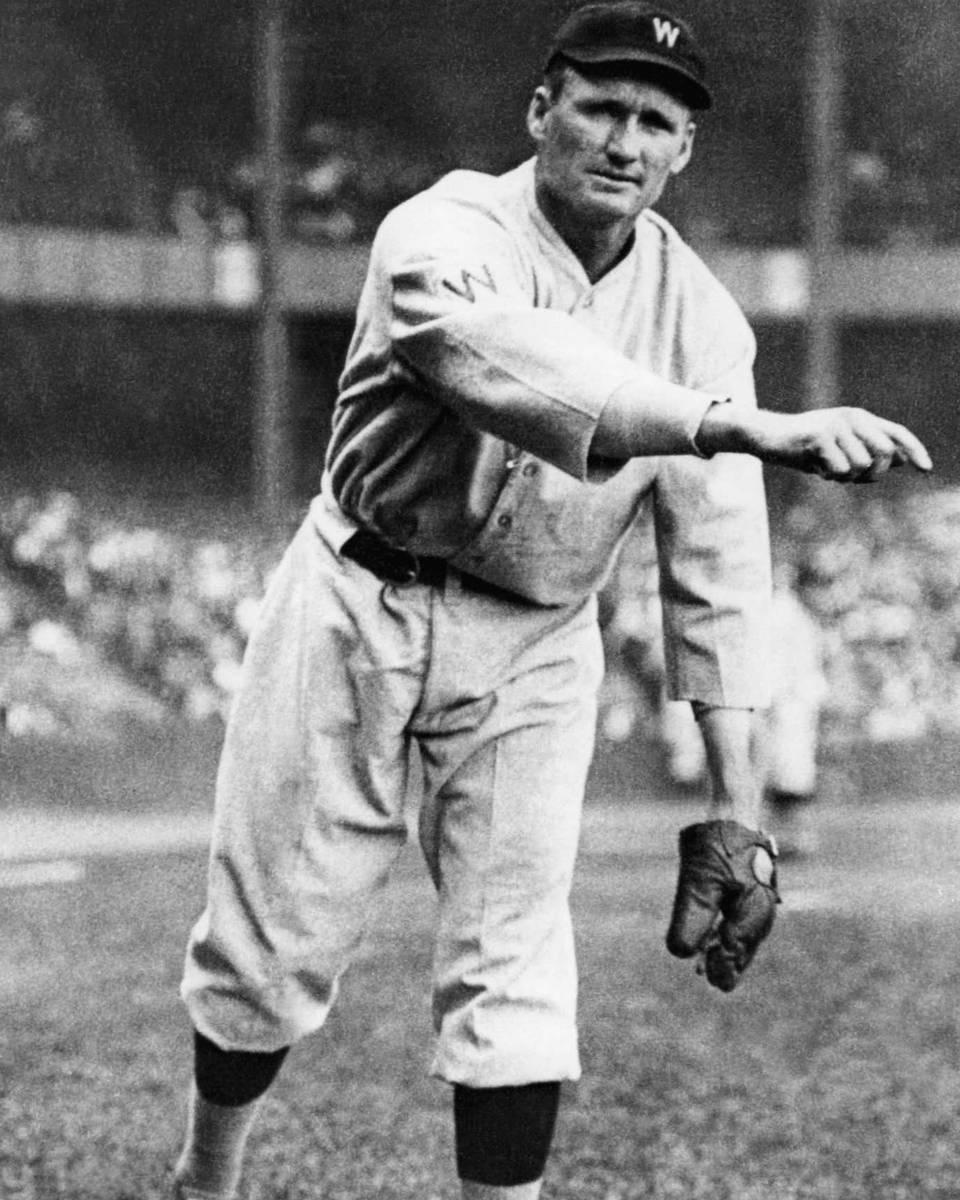

The team stumbled through its first 11 seasons, poorly financed and drawing few fans. Then a man who had played a key role in establishing the AL came to town. Clark Griffith would become the face of Washington baseball, first as manager, then as the hands-on majority owner until his death in October 1955. Five years later, his nephew would abandon the city Clark Griffith called home.

Washington had a team in the 12-team National League from 1892 through 1899. It was owned by brothers George and Jacob Earl Wagner, who were in the meat-packing business in Philadelphia. The Wagners routinely sold off any players who showed decent talent and never reinvested their profits into the franchise. Finishing no higher than sixth in its eight seasons, Washington ended 1899 in 11th place. The NL had enough of the city, along with Baltimore, Cleveland, and Louisville.

The Western League, founded by Ohio attorney Jimmy Williams, began play in 1892, but folded midway through the season. Financially strapped, Williams begged off giving it another try, so star first baseman Charles Comiskey recommended to team owners still interested that Cincinnati sportswriter Ban Johnson be hired to get the league going again in 1894. Comiskey and Johnson had become friends when the latter championed the Players League, to which Comiskey had jumped in 1890.

Johnson had in mind cleaning up the game by increasing the authority of umpires to discipline players and by banning profanity, among other attempts to make the games more appealing. His efforts worked well enough that several Western League teams outdrew the weaker National League franchises by the late 1890s. By then, Johnson and Comiskey, who had become owner of the team that became the White Sox, were working on a plan to create a major league to challenge the NL monopoly.

With Comiskey having moved his St. Paul team to Chicago and another league team having moved from Columbus to Cleveland, Johnson dropped the regional name in favor of the American League. Johnson, Comiskey, and Griffith, a star pitcher with the NL’s Chicago team, met in Chicago in late September 1900 to plan their strategy. Griffith had recently played a central role in establishing the Ball Players Protective Association. After the NL rejected Johnson’s plea to limit the drafting of minor leaguers and the association’s demand for higher pay, the AL began signing NL players for far more than that NL’s $2,400 salary cap.

With Griffith’s help, the AL was able to sign more than 100 NL players. Griffith personally persuaded 39 of 40 players he had targeted to jump to the new league. Only Honus Wagner resisted. Connie Mack also was heavily involved, recruiting players for the Philadelphia team he would manage and eventually own. Ohio industrialist Charles Somers, who wanted a new team in Cleveland, was the financial might behind the new league.

Griffith had become friends with Comiskey back in 1891 when the future White Sox owner persuaded him to sign with the American Association’s St. Louis team. After helping with the AL recruitment, Griffith became manager of Comiskey’s White Sox, then moved on to manage the Highlanders once the AL added a team in New York in 1903.

On December 7, 1900, Washington newspapers reported that Johnson had awarded an AL franchise to the District of Columbia. He put the owner of Kansas City’s Western League team, Jimmy Manning, in charge of the Washington franchise and gave him a share of the team, although Johnson retained financial control. In fact, at this point Johnson held a 51 percent stake in all eight AL teams.1 Manning arrived in Washington on December 17, 1900. A few days later, Johnson and John McGraw, who also was heavily involved with the new league, arrived in town. The three toured the city, looking at vacant blocks that might be suitable for a new ballpark. They settled on site in the Northeast section on Florida Avenue near Bladensburg Road, where Manning built a playing field and grandstands that he named American League Park.

The old National League Park on Georgia Avenue between U and W Streets, near Florida Avenue, wasn’t available because National League owners, in one of many efforts to thwart the AL, were scrambling to set up a high-level minor league that would have a team in Washington. The NL leased the old park to a Washington businessman, Will B. Bryan, who claimed to have the backing of the local electric company. The league never got off the ground.

The early years: Little success

Although Manning announced before the 1901 season that he had sold an interest in the team to Detroit hotel owner Fred Postal and that Postal was elected team president, Johnson remained the majority owner of the franchise with 51 percent of the shares. Manning, who was installed as the team’s manager, announced the inaugural Washington roster on February 1, 1901. All but two of the players had been with the Kansas City team in 1900. The opening day crowd of 9,772 included Spanish-American War hero Admiral George Dewey. The team finished the AL’s first season in sixth place. The year’s attendance of 161,661 ranked fifth in the league. According to Shirley Povich in his 1954 history, The Washington Senators, the team turned a profit during that first year.2

Manning lasted just a season as manager, team president, and part owner. To sign NL players, Johnson had established a pool of money available for AL teams, and Manning was happy to take advantage of it. Before he left, Manning tried to access league funds to sign Wee Willie Keeler, but Johnson balked. He was concerned that the earlier, and expensive, signing of Ed Delahanty might have been too aggressive.3

When Manning quit, he blamed “Johnson’s nature. … He brooks no opposition whatsoever.” Manning went back to managing Kansas City in the reconstituted Western League in 1902. His replacement, brought in by Johnson, with no input from Postal, was Tom Loftus, who had managed the NL’s Chicago team the two previous seasons. Lofton expressed his belief that spring training simply presented opportunities for players to injure themselves or “to have a good time and forget what they were there for.” He often read the day’s newspaper in the grandstands while the team practiced.4

During the 1901 season, a one-armed man who had the scorecard concession at American League Park began announcing lineups and substitutions to the patrons using a bullhorn. Previously, umpires had yelled changes to the press box, but few others in attendance could hear what they were. Thus, E. Lawrence Phillips became baseball’s first “megaphone man,” announcing changes to the fans at all Washington games from late 1901 until July 4, 1928, when an electrified public-address system was activated.

Before the 1902 season, Washington was able to sign four players from the Philadelphia Phillies, the prize being Ed Delahanty, who proceeded to lead the AL in hitting. The Phillies went to court to challenge this and other raids but could do no more than keep their former players from accompanying their new teams to Philadelphia for games with the Athletics. The team again finished sixth with 61 victories, the same as in the previous season. Still, the 1902 financial statement showed a profit of nearly $2,000.5 Pleased with the results, Postal gave Loftus a share of the team, but Johnson remained in control.6

Despite the profit, the 188,000 attendance was seventh in the league, slightly ahead of the failing franchise in Baltimore. Rumors that Johnson was about to move the Washington team to Pittsburgh were persistent enough that Postal had to issue a public denial. All this was settled when representatives of the NL met with Johnson in New York on December 11, 1902, with a plea for peace between the leagues. An agreement reached in January kept Delahanty, who was about to jump to the Giants, in Washington. Although he resisted the decision well into spring training, Delahanty was among nine players awarded to the AL, while seven others were given to the NL.7

As part of the deal, Johnson agreed not to put a team in Pittsburgh. He already had planned to set up a team in New York, while abandoning Baltimore. That move was seen as expanding the Senators’ home territory, eliminating a nearby franchise.8

Postal, who was little more than a figurehead, remained as team president in 1903 with Loftus staying on as manager. The Opening Day game, on April 11, attracted a crowd of 11,950 and featured the first game ever played by the AL’s New York team, then known as the Highlanders and managed by Griffith.

Delahanty’s fatal fall from a railroad bridge in July was the darkest moment of a season that saw Washington fall into last place. This was the first of four cellar finishes over nine years. (The other five were seventh place.) The team’s futility gave birth to the quip: “Washington: First in war, first in peace, and last in the American League,” which appeared in the June 27, 1904, Washington Post and was credited to Charles Dryden, the era’s most famous baseball writer and humorist.

Hardly a surprise, Loftus wanted to spend more to acquire players. The relation between Postal and Loftus deteriorated enough during the season that Postal in August threatened to resign. Johnson came to town and entertained an offer for the team from Charles Jacobson, a Washington businessman. Jacobson, however, balked at assuming the team’s debt, once he found the amount was between $12,000 and $15,000. When no one else stepped forward by early March, Johnson bought the shares of the team the league didn’t already own, including those of Postal and Loftus, for $15,000 and then paid the bills.9

Finally, local ownership and a star pitcher

Later that month, Johnson was able to sell most of the team’s stock to a group of local businessmen, organized by former Associated Press reporter and baseball writer William Dwyer. The main financial backer of the group was Thomas C. Noyes, an editor at the Evening Star, Washington’s largest newspaper. The Noyes family owned the paper. Also part of the group was Wilton J. Lambert, who had been the team’s attorney since 1901, and Scott C. Bone, managing editor of the Washington Post who years later became territorial governor of Alaska. Lambert was named club president and Dwyer vice president, general manager, and treasurer.10

Later that month, Johnson was able to sell most of the team’s stock to a group of local businessmen, organized by former Associated Press reporter and baseball writer William Dwyer. The main financial backer of the group was Thomas C. Noyes, an editor at the Evening Star, Washington’s largest newspaper. The Noyes family owned the paper. Also part of the group was Wilton J. Lambert, who had been the team’s attorney since 1901, and Scott C. Bone, managing editor of the Washington Post who years later became territorial governor of Alaska. Lambert was named club president and Dwyer vice president, general manager, and treasurer.10

With the two major leagues at peace, the Senators moved into the expanded National League Park (renamed American League Park, of course) on Georgia Avenue — a location at which the team would remain for the rest of its tenure in Washington. Some of the grandstands from the old park were moved and reinstalled to increase capacity at the Georgia Avenue site.11

The new owners took control of a club on the way to its worst record: 38-113, 55½ games out of first. After firing Loftus a week before the season started, Dwyer made catcher Malachi Kittredge interim manager for 17 games until Patsy Donovan won release from his Cardinals contract. While AL attendance was up overall by 750,000, the Senators drew just 132,344. By May, Dwyer had had enough and left town.12

In January 1905, Noyes led a new local group that acquired 55 percent of the team’s shares. The league held the remaining 45 percent. Noyes assumed the presidency. Others who bought shares included Bone of the Post, who two years later founded the Herald. With Noyes and Bone involved, the team at least was assured of newspaper coverage. First baseman Jake Stahl, who had joined the Senators the previous season, was named player-manager.

In an effort to leave the past behind, the team held a preseason contest to adopt a new name. The choice was Nationals, although most fans and newspapers continued to call the team the Senators. Washington officially would remain the Nationals through the 1956 season, thus the nickname Nats often used in headlines.

The 1905 team got off to a good start — indeed, no start could be worse than 0-13 that began the ’03 season — and remained in the first division until midseason. Injuries to key players and an illness that put Stahl out of action led to a slump that dropped the team to seventh place, but the 64 victories were 26 more than in ’03, and the players shared a $1,000 bonus promised by Noyes in April if Washington avoided the cellar. At their meeting in December, stockholders were presented with a report that the team had spent $12,910 to acquire players and had sold players for $3,125. Noyes was drawing a salary of just $600 a year as team president.13

Washington finished seventh again in ’06, but won nine fewer games and finished 37½ games out of first. At end of the year, Stahl was replaced as manager by Joe Cantillon, a fiery former umpire. Stahl refused to play for Washington and ended up with a semipro team in Chicago when the Nats were unable to trade him before the 1907 season.14 Noyes gave Cantillon a three-year contract at a $7,000 salary and a promise of 10 percent of the team’s profits.15

Cantillon did little to improve Washington’s performance, but he was responsible for the Senators discovering and nurturing the greatest player ever to wear the team’s uniform: Walter Johnson, who made his debut in August 1907. The new ownership bade goodbye to Cantillon in early 1910 and hired Jimmy McAleer as manager. He wasn’t much better than Cantillon, producing two seventh-place finishes, but he was around for the start of a Washington tradition that lasted as long an AL franchise remained in the city. President William Howard Taft threw out the ceremonial first pitch on Opening Day in 1910, something each of his successors did through Richard M. Nixon (with a vice president or other officials occasionally pinch-hitting).

Weeks before the 1911 season was to begin, a fire set by a plumber’s torch burned the Senators’ wooden ballpark to the ground. Noyes fulfilled a pledge that a new park would be built before the season started. The cost of the project would lead to the most significant development in the history of the franchise.

The arrival of Clark Griffith

After 5½ seasons managing New York and two back in the NL with Cincinnati, Griffith was questioning whether he should abandon baseball. Unlike Comiskey and Mack, he had not been able to secure even partial ownership of a team. Now his old teammate McAleer was leaving Washington to become part-owner of the Boston Red Sox.

During the 1911 World Series, Washington’s ownership group sent minority stockholder Edward Walsh to approach Griffith about managing the team in 1912. Griffith previously had become friends with Noyes. Soon after, Griffith met with the stockholders and was told the team was about to double the franchise’s outstanding shares to pay for construction of the new ballpark. Griffith offered to buy as many shares as the other owners would allow, but he didn’t have the means to match the price several of the owners were asking. Noyes and Walsh, however, agreed to sell shares to Griffith for what they had paid. Along with another partner, Benjamin Minor, the three agreed to sell 1,200 shares to Griffith for $12.50 a share. He would then purchase another 800 shares at $15 each from other stockholders. The 2,000 shares would give Griffith a 10 percent share of the team and make him the largest single stockholder.16

Griffith had $7,000 from selling the cattle on his Montana ranch.17 He approached Ban Johnson for a previously promised $10,000 loan, but the league president declined. Desperate not to miss this opportunity, Griffith mortgaged his ranch for $20,000, bought his share of the team and on October 27, 1911, signed a three-year contract as manager at $7,500 a year. Although Johnson refused to lend Griffith money and their relationship frayed, Johnson seemed pleased that Washington signed him to manage. “It’s a good thing for the Washington club to get an experienced shrewd and wise baseball genius,” Johnson told Sporting Life.18

Eight years earlier, Johnson had played a part in preventing Griffith from acquiring part-ownership of the Detroit Tigers. Griffith had led a group of Chicago investors that bid $40,000 to buy the team, but the AL president wanted Griffith to remain as manager in New York.19

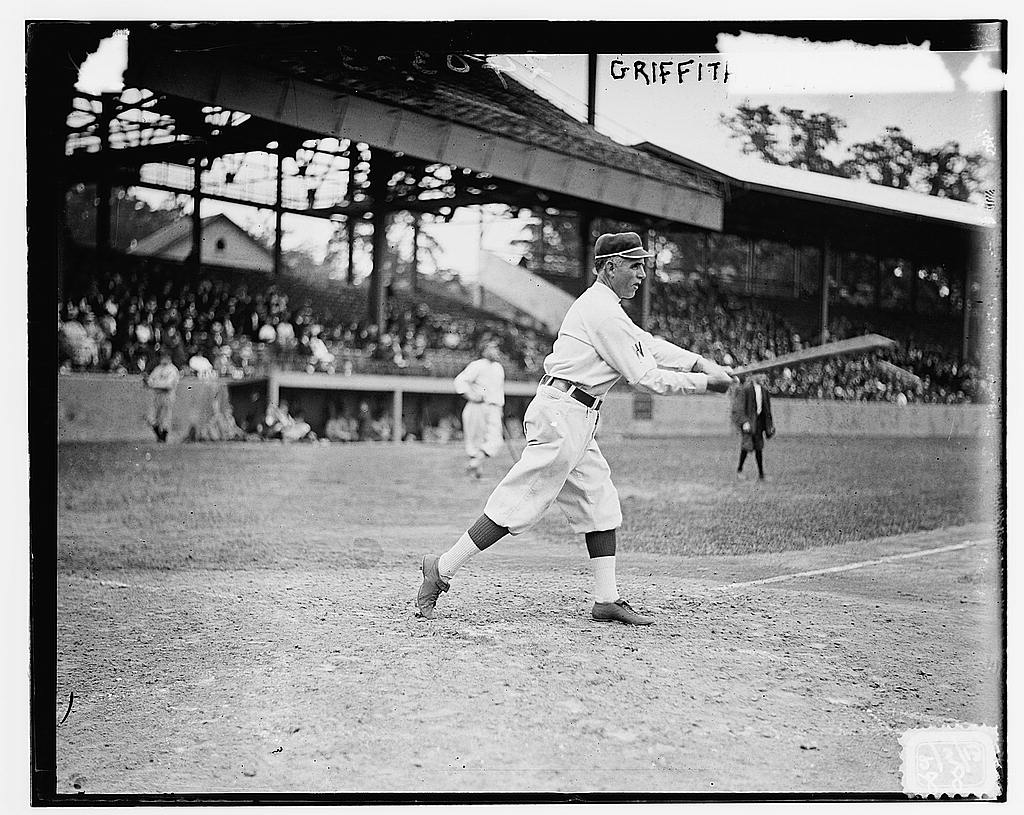

Washington Senators manager Clark Griffith takes a swing during infield practice in 1913. (Library of Congress, Bain News Service)

Behind the strong arm of Walter Johnson, Griffith managed consecutive second-place finishes for Washington in 1912 and 1913, winning 91 and 90 games. Gate receipts jumped 50 percent as attendance rose from 244,884 in 1911 to 350,663 in 1912 (still just fifth in the AL, however). The team reportedly turned a profit of $90,000, and the board of directors declared a dividend. The success won Griffith, already widely known as the Old Fox, a seat on the board and a raise to $10,000 a year. Several players received bonuses.20

Griffith lost an ally in August 1912 when Noyes died at age 44 of pneumonia. The board chose Minor as his successor. Unlike Noyes, Minor insisted that Griffith clear player transactions with him. Griffith soon made it clear he wasn’t about to abide by that rule.

Before the 1913 season, Griffith went for all the marbles. He wrote a personal check for $100,000 to purchase Ty Cobb from Tigers owner Frank Navin, asking only that Navin give him two weeks to make good on the check. The Senators board was aghast. Griffith’s plan was to sell 100,000 advance tickets for $1 that fans could use for any game they chose. Navin, however, sent the check back.21

With an eye fixed on the bottom line, Minor tried to renegotiate Walter Johnson’s salary after the 1914 season, despite pleas from Griffith and the looming threat of the Federal League. After Johnson had agreed to a deal with the Federals, Griffith enlisted Fred Clarke of the Pirates to visit the star pitcher and persuade him to re-sign with Washington on the strength of a promise of a better offer. Johnson eventually got a five-year contract at $16,000 a year from Washington.22

Griffith’s teams couldn’t sustain the 1912-13 pace, but they remained competitive. Still, attendance faltered. The 1917 total was the lowest in the league, although the widely reported figure of 89,682 is surely an undercount. (A game-by-game tally with figures for all but seven days from Baseball-Reference shows a total of 145,384 for 72 dates.)23 One reason for the decline was the nation’s entry into World War I just before the season started. Although the federal government added an estimated 25,000 employees in Washington during the war, many of them worked well into the evening. Senators games started no later than 3:30 P.M. The team’s poor play — it never climbed higher than fifth in the standings — certainly didn’t help.

The team lost $43,000 in 1917, which forced members of the board to underwrite personal loans to meet expenses.24 The declining trend prompted talk about whether a team in Washington was viable.25 A rebound in the war-shortened 1918 season, which put Washington back in the middle of the pack in attendance and third in the standings, tended to quell the rumors. In May, for the first time, the Senators were allowed to play on Sundays. The adoption of daylight saving time, which let Washington start its games an hour later, likely helped, too.26

Still anxious to gain a greater share of ownership, Griffith in 1917 sold his 4,000-acre ranch in Craig, Montana, for $85,000, less what he owed on the mortgage.27 He intended to use the money to partner with John Wilkins, a Washington businessman, to acquire majority control of the Senators. When that deal stalled, he approached Branch Rickey, then with the St. Louis Browns, about making an offer, but Rickey soon after moved into management with the Cardinals.28

Although he didn’t get the five-year deal he sought, Griffith had signed a three-year contract in 1915 to keep managing. But he continued to seek a larger ownership role. Before that would happen, however, Griffith gained a considerable amount of favorable notice for himself and Organized Baseball by promoting a drive to supply equipment to military training camps during the war. Griffith raised more than $100,000 in small donations to send supply ships full of bats, balls, and gloves to the American Expeditionary Force in Europe, but a German U-boat sank the first such vessel before its cargo was delivered.

The Nats manager also interceded to prevent league President Johnson from shutting the season down in July after a government ruling that ballplayers needed to serve in the military or work in an industry essential to the war effort. Griffith knew Secretary of War Newton D. Baker and got him to agree that if the players participated in military drills — with their baseball bats instead of rifles — the regular season could continue until Labor Day with another two weeks for the World Series. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt took part in some of the drills.29

Griffith becomes majority owner

After a seventh-place finish in the standing and in attendance in 1919, Griffith met with resistance from his fellow shareholders when he tried to get them to spend money to improve the roster. Frustrated, he turned to old friend Mack, who introduced him to William E. Richardson, a wealthy grain exporter and business partner of the Athletics’ majority stockholder, Tom Shibe. “Come back and see me after you’ve rounded up enough stock to give us controlling interest,” Richardson told Griffith.30

Offering $15 a share, Griffith found he and Richardson could purchase 85 percent ownership. The president of the Metropolitan National Bank in Washington had enough faith in Griffith’s baseball savvy to lend him the $87,000 he needed to partner with Richardson to close the deal. The two split the new shares equally, with the 2,700 shares Griffith already owned giving him majority control. Richardson granted Griffith permission to vote his shares at stockholder meetings and pledged to stay hands-off in on-field matters. This partnership and operating agreement lasted until Richardson’s death in 1942 and the death of his twin brother, George M. Richardson, who inherited his shares, in 1948.

Assuming the club presidency, Griffith appointed Edward B. Eynon Jr. as business manager. Eynon, who had headed the Liberty Loan drives in Washington during World War I, stayed with the team until his death, a month after Griffith’s own, in November 1955. He was vice president and secretary-treasurer by then. Eynon often served as Griffith’s golf partner as his boss gradually improved his game until the Old Fox was able to card rounds as low as the upper 70s.31

By the 1920 season, Griffith realized that as an owner he had enough to do without being the field manager. He likely was the last majority owner of a major-league team to wear a uniform as the manager.32 In 1921 he turned those duties over to the first of several player-managers he would employ, longtime shortstop George McBride. McBride led the team to 80 victories and a fourth-place finish, but suffered a head injury in August when he was hit with a throw during an infield practice. Another player-manager, longtime star outfielder Clyde Milan, took over in 1922, but the team fell to sixth. Then it was veteran infielder Donie Bush’s turn to manage. Disappointed that one of his best-hitting clubs finished under .500 in 1923, Griffith then turned to his 27-year-old second baseman, Bucky Harris, who led the team that would win Washington’s only world championship. The 1924 season was the start of his three stints totaling 18 years as Washington’s manager, the last ending a year before Griffith’s death in 1955.

In 1921 Griffith began to make improvements to the ballpark, of which he became owner when he took over the team. It had been rebuilt in a hurry after the March 1911 fire and needed upgrading. Griffith built an office for himself under the grandstands, near the new main entrance he had installed on the Florida Avenue side of the ballpark.33 For the next 30 years, he would regularly play cards with old friends there or regale sportswriters with stories about his early days. One thing Griffith did not change was the cavernous depth of the stadium’s outfield. Until the fences were moved in a bit in the early 1950s, Washington’s ballpark was a notoriously difficult place in which to hit home runs.

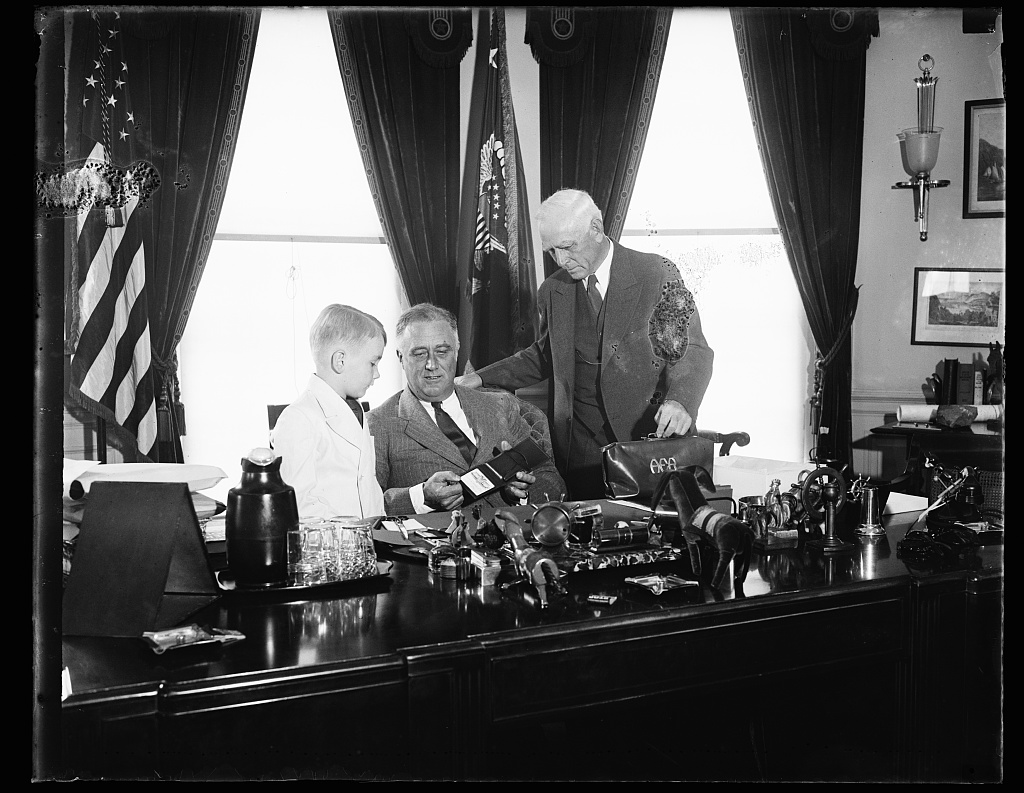

After he became the majority owner, Griffith solidified the tradition of the presidential opener in D.C. by personally presenting the chief executive with two season passes each spring. The presidential box at the stadium was always available if the man in White House wanted to take in a game other than the season’s opener.34

A major change came in the childless Griffith’s personal life in the fall of 1922. Appalled at the poverty of her alcoholic brother, James Robertson, and his family in Montreal, Addie Griffith, Clark’s wife, brought back two of the Robertson children to live with them in Washington. The children, Calvin and Thelma, adopted the Griffith name. After their father died, the rest of the family eventually moved to Washington, with Calvin Griffith’s brothers and a sister taking jobs with their uncle’s team. One of the brothers, Sherry Robertson, ended up playing for the Senators. Another sister, Mildred, became Griffith’s executive secretary.

The Washington Post’s banner headline on September 30, 1924, after the Senators clinched the American League pennant. (Newspapers.com)

A bigger stadium and a championship team

In August 1923 Griffith announced plans to substantially increase the seating capacity to 35,000 in what became known that season as Clark Griffith Stadium. After construction of a second deck that extended over the field farther than the lower deck, 12,000 seats were added to the existing 20,000. Additional seats could be added for football games, frequently held there, to allow seating for up to 38,000. Revenue from renting the ballpark for college and later professional football games provided a source of revenue that helped keep Griffith afloat financially. With segregation the norm in the nation’s capital, Griffith built a right-field pavilion for black fans attending Senators games. He began making the ballpark available to nearby Howard University for its annual football game with Lincoln University. The Thanksgiving Day meeting of the two leading black colleges attracted capacity crowds.35

By the 1920s, the neighborhood surrounding Griffith Stadium has become populated by middle-class black families, many of them doctors, lawyers, or government workers. Griffith was enough of a businessman to know that cultivating the city’s growing black population made economic sense. He let teams from the segregated high schools play there. A black evangelical minister attracted more than 25,000 followers to his baptism services in the ballpark. However, after an exhibition game between a black professional team and a white one nearly became violent in the fall of 1920, Griffith banned interracial baseball games there for the next two decades.36

Even before the ballpark’s expansion, Washington fans responded favorably to Griffith’s ownership. Attendance increased from 234,000 in 1919 to almost 360,000 in 1920, then to more than 456,000 in both 1921 and ’22. Griffith was making money. The team’s balance sheet showed profits of $153,608 in 1920 and $133,410 in ’21. A disappointing sub-.500 finish in 1923 contributed to an attendance decline to the 1920 level, but that coincided with a league-wide drop. Still, Griffith turned a profit, albeit a modest one: $33,167.37 Stockholders received small dividends those first three seasons.

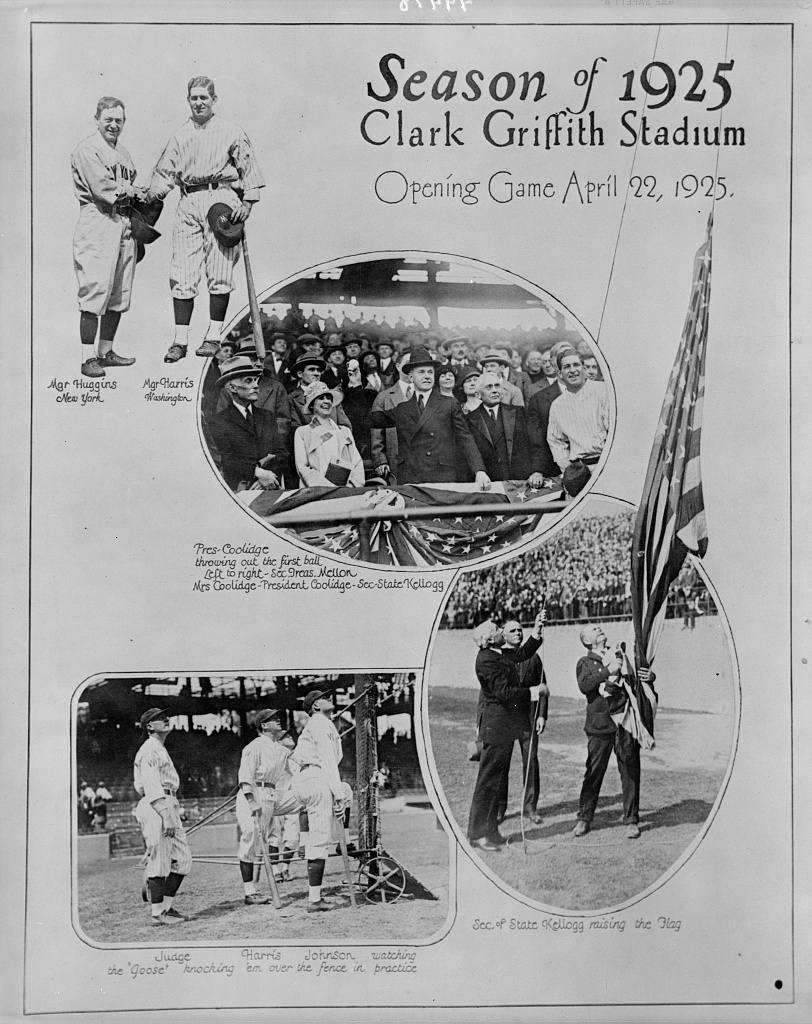

Griffith used some of the profits to renovate the home and visitors clubhouses and put new sod on the infield, making it among the best in baseball. Increased seating and other improvements in place for the 1924 season proved fortuitously timed. Attendance reached a then-record 586,310 in Washington’s first pennant-winning season. The total was fourth best in the AL, even though Washington remained by far the league’s smallest city. Gate receipts for the 1924 World Series topped $1 million. The second pennant season, 1925, drew 817,199 people to Griffith Stadium. The team’s profits jumped to $231,037 in 1924 and $408,746 in ’25, a figure that Senators would not exceed until 1947. Adjusted for inflation and not boosted by rent from football’s Redskins, 1925 undoubtedly was Griffith’s most profitable season. It provided him the means to build a substantial house in Northwest Washington adjacent to Rock Creek Park.38

The 1920s were the beginning of the era when player trades and acquisitions were no longer the purview of the field managers, but were more often made by general managers hired by wealthy owners. Griffith and Mack, who searched for prospects on independent minor-league teams, were becoming anachronisms. Rickey represented the future when he began acquiring or establishing working agreements with what became known as farm teams. Other organizations followed Rickey’s lead. That Griffith continued to go it alone is often cited as one of the reasons his teams would no longer contend after World War II.39

For the 10-year stretch from 1924 through 1933, however, Griffith’s successful trades and savvy eye for talent brought Washington three AL pennants and three other seasons of 92 or more wins. He was helped most by two men: Joe Engel, a former Senators pitcher who became Griffith’s right-hand man and trusted scout, and later by Joe Cambria, an Italian by birth who became the premier discoverer of Cuban talent that Griffith so often relied on to bolster his rosters. Those two (both of whom later became minor-league club owners), along with Calvin Griffith, the nephew whose role would increase, formed Clark Griffith’s brain trust over the years on baseball matters. Whatever current or former Senator was managing the team — most often Bucky Harris or Ossie Bluege — would be the only other person in the mix.

A losing record in 1928 cost Harris his job and drove attendance below 400,000. The next season, Walter Johnson’s first as manager, was even worse. The Senators finished 10 games under .500, despite having the third highest payroll in the AL.40 The number of fans showing up fell back to the 1923 level, and Griffith had his first taste of red ink: a loss of nearly $44,000. Then, 94 wins and a second-place finish in 1930 pushed attendance up to 614,972. The team’s profit the year after the stock market crash was $56,808.

The Washington Senators celebrated their American League pennant on Opening Day 1925 with a ceremony that included President Calvin Coolidge throwing out the first ball (center) and Secretary of State Frank Kellogg raising the American flag (bottom right). At top left, Senators manager Bucky Harris shakes hand with Yankees counterpart Miller Huggins. (Library of Congress, National Photo Company Collection)

Surviving the Depression

As the Great Depression grew worse, the financial success didn’t last. Major-league attendance, more than 10.1 million in 1930, fell to 8.4 million in ’31 before bottoming out at just over 6 million in 1933. Griffith, however, did well weathering the storm. His team lost $28,000 in 1931, a year when only the Yankees and Athletics in the AL made money. Only Philadelphia avoided a loss in ’32, while four teams lost far more than Griffith. Washington won its last pennant in 1933, but Griffith could not quite turn a profit: The team lost $501. The other seven AL teams had far greater losses; Philadelphia’s $21,047 was the next smallest. Griffith actually made money in six of the next seven season leading up to World War II.41

Despite a small profit in 1934, the defending champs faded badly. Griffith’s team had the second highest payroll in the league in 1933 at $187,059.42 At the end of the ’34 season, repayment of a $124,000 bank loan was due. His latest playing manager, Joe Cronin, had married Calvin’s older sister, Mildred. Griffith now was Cronin’s in-law as well as his boss. Griffith would say years later that the family relationship put undue pressure on Cronin, but the $250,000 that Boston paid for the future Hall of Fame shortstop and the dumping of Cronin’s $23,000 salary eased the pain and kept the Senators in the black.43

By the early 1930s, more and more minor-league teams had working agreements with the majors. After a couple of false starts that year, Griffith finally found a minor-league team from which to develop talent. The Southern Association charter prohibited team ownership by a major-league franchise, but Griffith got around that by putting up the money to buy the Chattanooga club in Engel’s name. As president, the longtime scout made the team a financial success with frequent promotions and appearances by the baseball clowns Al Schacht and Nick Altrock.44 Still, a one-team farm system paled in comparison with what the Cardinals, Yankees, and others had established.

In a belated effort to compete, Griffith tried to buy two low-level minor-league teams in the Southeastern League with money left over from dealing Cronin, but that circuit folded. In March 1935, with Cambria acting as the middleman, he purchased the Lancaster team in the Pennsylvania State League and Harrisburg in New York-Penn League.45 (Today’s Harrisburg team in the Eastern League is still called the Senators and coincidentally is a Washington Nationals affiliate.) Meanwhile, however, attendance in Washington fell to 255,011 that season, leaving Griffith especially strapped for cash. Before the end of the decade he had disposed of the two Pennsylvania teams and sold his interest in Chattanooga to Engel, although the two still maintained a relationship. That left him with only a Class B team in Charlotte, where he had dispatched Calvin to run the front office and serve as manager, and Orlando in the Class D Florida East Coast League.46

The next season, Cambria brought Griffith the first of a steady stream of Cuban players: Bobby Estalella. The third baseman-outfielder was of mixed race, as opposed to Castilian, and had dark enough skin that opposing players taunted him with racial epithets. Both Shirley Povich and Burt Hawkins, a former Washington Evening Star sportswriter, told author Brad Snyder that they considered Estalella to be black,47 as did some of his teammates and many opponents.

When the 1936 All-Star Game was played before thousands of empty seats in Boston, Griffith convinced his fellow owners that he could produce a full house if the game were played in Washington in 1937. That he did. The capacity crowd of 32,000 at the 1937 game included President Franklin D. Roosevelt and dozens of other dignitaries.48

Griffith’s favorite ballplayer, Walter Johnson, was one of the radio announcers for the All-Star Game, and three years later, in 1940, Griffith hired him to broadcast Senators games. Johnson also doubled as the public-address announcer that season. Johnson was supposed to work with a play-by-play man, but with a tight budget he ended up handling play-by-play. The next season, however, the man who would remain the radio voice of Washington baseball through 1956, Arch McDonald, returned from a year in New York, ending Johnson’s time in the broadcast booth.49

A vigorous early opponent of night baseball, Griffith eventually changed his tune. In 1941, with the help of an interest-free loan from the league,50 he spent $230,000 to install lights at the ballpark.51 The boost in attendance thanks to night baseball helped the lighting system pay for itself in two years.52 The Senators were allowed to play 21 night games in 1943, seven more than other teams could. By 1944, he argued for unlimited night baseball at his ballpark and, with Roosevelt’s encouragement, got his wish.

After selling Cronin, Griffith had brought Harris back as manager. This second term for Harris lasted eight seasons but produced just one with a winning record, 82 wins and a tie for third in 1936. Ossie Bluege succeeded Harris in the depth of World War II and surprisingly produced a second-place finish in 1943. But with virtually the same team a year later — Mickey Vernon was drafted, but Joe Kuhel produced essentially the same numbers — the 1944 team became the first under Griffith to finish last. Still, attendance relative to the entire league remained strong: the third highest in ’43 and fourth highest in ’44.

As he had done during World War I, Griffith used his Washington connections to help keep baseball alive after the attack on Pearl Harbor brought the nation into World War II. Although Commissioner Kenesaw Landis had written to President Roosevelt asking that baseball be allowed to continue, the commissioner had been a vocal opponent of the New Deal. So when Roosevelt sent the “Green Light” letter in February 1942, Griffith, a friend of the president, took credit for the decision.53

After losing $11,358 in 1941, Griffith made money during the war years. Despite the 90 losses in ’44, the club made a profit of more than $90,000 and paid a dividend to stockholders. The Senators by this time were not Griffith’s sole source of revenue. Football’s Redskins had begun renting Griffith Stadium in 1937 after moving from Boston. In 1940 Pittsburgh’s Homestead Grays of the Negro National League began playing more than half of their league games at the ballpark.

As successful as the Grays were on the field, a dominance matching that of the Yankees, the games in Washington drew smaller crowds the first two seasons than the team did on the road. Once Josh Gibson returned to the Grays after playing in Venezuela, and Satchel Paige began appearing with his Kansas City team or with all-star squads, the Grays began to draw better, helping the team’s bottom line and that of Griffith, who provided ticket-takers and ushers and controlled concessions. Playing 11 home games at Griffith Stadium in 1942, the Grays drew 127,690 fans, an average of 11,608 a game.54

Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith, right, presents a “gold pass” to President Franklin Roosevelt before Opening Day on April 13, 1936, at the White House in Washington, D.C. The pass allowed the President to attend any major-league baseball game. At left is Sandy McDonald, the 8-year-old son of a local radio broadcaster. (Library of Congress, Harris & Ewing Collection)

One last run, but clinging to the past

Rosters in 1945 were stocked with players too old for the draft — or the big leagues, under normal circumstances — or otherwise medically ineligible. (Three Nats knuckleball starters were 4-F.) Yet despite having Hall of Fame caliber Negro League stars playing in his ballpark and a black fan base to support them, Griffith continued to ignore appeals from sportswriter Sam Lacy and others to break baseball’s color barrier and sign one or more black players.55 Instead, he encouraged the Negro Leagues to become more organized with the ultimate goal a postseason series between the white and black championship teams.56 Not until 1954 did Washington feature a black player, and even then the player was not an African-American but a Cuban — this time an admittedly black Cuban.

Griffith’s reliance on stadium rentals for revenue likely contributed to Washington’s missing out on the AL pennant in 1945. He had agreed to have the Senators end their home season on September 18 so the Redskins could use the field for a late-September home game. The Senators season ended on September 23 when Washington split the last of nine doubleheaders in three weeks, this one with the Athletics in Philadelphia. That left the Senators, at 87-67, a game and a half behind the first-place Tigers, 86-64 with four games left.

The Tigers shut out Cleveland in the first game of a doubleheader on September 26 but lost the second game and still needed one win to clinch the pennant. If the Tigers dropped their final two games, Washington and Detroit would be tied. Rain in St. Louis kept the Tigers idle for three days. On October 1 Hal Newhouser, in relief, won the clincher when Hank Greenberg’s ninth-inning grand slam beat the Browns. The Griffith-era Senators never again would come as close.

Despite finishing second, not a single member of the 1945 Senators hit a ball over the outfield fences at Griffith Stadium. The only home run hit at home that season was an inside-the-park job in August, by the 39-year-old Kuhel, no less. Griffith was no fan of home runs. In the early 1920s, no doubt influenced by the cavernous dimensions of his ballpark, he had campaigned to change the rules so that balls hit over fences of less than a certain distance would not count as homers. Beyond that, Griffith was a devotee of speed and defense. He tried to build teams that reflected his preferences. All of which makes the oft-repeated quip attributed to him so out of character: “Fans like home runs, and we’ve assembled a pitching staff to please our fans.” No one seems to recall exactly when he said this, although supposedly it was after he watched his team take a beating.

Being part of a pennant race in 1945 produced the second highest attendance to that point in Washington history — 652,660, fourth best in the league and just 5,000 fewer than third-place Chicago. Only the pennant-winning team in 1925 had drawn more. The best was still a season away, however. With the war ended and demobilization proceeding slowly, 1,027,026 fans attended games at Griffith Stadium in 1946. That turned out to be the only season Washington would top one million. The $357,414 profit that year was the best Griffith had done since 1925.

Although attendance fell to 850,758 (still the second highest in team history), Griffith did even better in 1947. His team earned a record $457,195.57 Stockholders received small dividends from 1943 through 1948, most of the money, of course, going to Griffith and Richardson. Despite Griffith’s perpetually tight operating budget, the team paid dividends in 23 of the 36 years he was the majority owner. Between 1920 and 1956, the last time a dividend was declared, the Senators paid shareholders a total of $1,224,040. Only the Tigers and Indians paid out more during the same period.58

Amid the postwar boom in attendance and interest in the game, the Senators’ performance on the field deteriorated rapidly. After finishing fourth, two games under .500, in 1946, Washington lost 90 games in ’47 and 97 in ’48, somehow managing to finish seventh each year. But 1949 turned out to be by far the worst season since Griffith took over as owner. A 50-104 record left Washington in last place, 47 games behind the first-place Yankees. His inability to sign, develop, or trade for enough solid players had become increasingly apparent. With the exception of Mack, who hardly was doing any better, wealthy businessmen owned all the other major-league teams. Attendance, although still robust by Washington standards at 770,745, was seventh in the league, ahead only of the anemic Browns. To top it off, the Senators lost money — albeit just $18,323 — while every other team in the AL turned a profit in 1949.59 The demise of the Negro National League after the ’48 season ended both the Homestead Grays’ stay at Griffith Stadium and a source of rental revenue.

The news got worse for Griffith after the season. The Richardson family had been trying to find a buyer for the family’s 40.4 percent stake in the team. Griffith had an agreement with William Richardson to be able to match any offer for his share. He believed the agreement continued when George Richardson inherited his brother’s stake. Once George died in August 1948, his heirs actively sought bids for their shares. Griffith made several offers, but was outbid by John J. Jachym, a Jamestown, New York, businessman and war hero who had owned the minor-league team there. With the financial backing of Pennsylvania oilman Hugh Grant, Jachym paid a reported $550,000 for the Richardson shares.60

Griffith learned that Jachym had become part-owner when his would-be new partner walked into the Griffith Stadium office just before Christmas in 1949. Unlike the Richardson brothers, Jachym had no intention of being a silent partner. As a young man before the war, he had worked for Branch Rickey. He had done some scouting then and more recently for the Tigers, so he had a background in baseball. Griffith, however, felt nothing but resentment. With his family owning just 44 percent of the team’s stock, Griffith was afraid Jachym would try to gain majority control.61

Although they declined to sell their shares to Griffith, now 80 years old, he persuaded enough of the minor stockholders to vote with him at January 1950 board meeting to deny Jachym any role with the team. Griffith also rejected Jachym’s suggestion that Washington buy the available Buffalo franchise in the International League.62

Acquiring a top-level minor-league team was just one of many ideas Jachym offered for improving the fortunes of the Washington franchise, but Griffith would have none of it. His unfavorable first impression of Jachym apparently was sealed when his new partner told Griffith how much he admired Rickey. Griffith retained a long-standing dislike of both the National league and Rickey-inspired farm systems.63

Unable to get his foot in the door, Jachym held his shares for six months before selling them to a Griffith ally, H. Gabriel Murphy, for a profit of at least $80,000, taxed at the long-term capital-gains rate. Griffith promised Murphy, a Washington insurance broker, the right of first refusal on his own shares, if the Griffith family should decide to sell. In return, Murphy sold Griffith the shares he needed to hold more than 50 percent and promised to be the kind of silent partner the Richardson brothers had been.64 He was given a seat on the board and named team treasurer. The rejection of Jachym and his progressive approach meant the best chance for the long-term survival of the Senators in D.C. likely had passed.

Griffith made one concession to modernizing his stadium in 1950: He finally shortened the distances to the wall in left and left-center field, which had been more than 400 feet, making Griffith Stadium just a bit less of a graveyard for fly balls.(65) After his uncle’s death, Calvin Griffith in 1956 installed a beer garden in front of the bleachers in left. Beer was sold for the first time at Griffith Stadium in August of that year, the last the eighth A.L. ballparks to allow alcohol sales. Calvin also put up a fence in front of the left-field stands, shortening the distance to 350 feet from home plate in an effort to help power hitters Roy Sievers and Jim Lemon.65

Five seasons of 20 games or more under .500 ended with the return of Bucky Harris as manager for the 1952 season. Washington won two games more than it lost (78-76), yet could finish no higher than fifth. Harris, who won a pennant in New York in 1947 before losing a three-way race — and his job — in ’48, used his knowledge of the Yankees roster and farm system to Washington’s advantage, suggesting deals to Griffith that strengthened the Senators. The acquisitions of Jackie Jensen, Jim Busby, and Bob Porterfield were prime examples. Porterfield was the top pitcher in the AL in ’53, the main reason the team was able to finish exactly at .500 and in fifth place again.

A sad ending

The final two years of Griffith’s stewardship of the team and of his life surely would not rank as his most satisfying. When the Senators finished 22 games under .500 in 1954, Griffith let Harris go for the third time (urged on by Calvin Griffith), and for the first time, turned to a manager who had no previous connection with Washington, Charlie Dressen.

For reasons that are unclear, Griffith also supported the move of the St. Louis Browns to Baltimore, some 30 miles up the road from Washington, for the 1954 season. Knowing that another American League team so close could hurt Washington attendance, Calvin Griffith opposed the move. (Long term, the presence of the Orioles no doubt weighed in favor of leaving Washington without a team for 33 years. Orioles owner Peter Angelos wasn’t about to agree willingly to give up his territorial rights as Clark Griffith had done.)

The popular Douglass Wallop novel The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant, published in 1954, put an exclamation point on the downtrodden nature of Washington baseball. The book was turned into the hit Broadway musical Damn Yankees, and the next year, as if on cue, the Griffith team was losing more than 100 games for just the second time in his 44 years in Washington. Charles Dryden’s shopworn quip about Washington being “last in the American League” gained renewed truth. The laughs at the expense of the Senators had to weigh on the 85-year-old Griffith. He was hospitalized with nerve pain and died several days later, on October 27, 1955. His funeral was front-page news nationwide. His will left his shares to Calvin and his sister Thelma, with each receiving 25.5 percent of the team. Thelma let Calvin vote her shares.

Calvin Griffith, already executive vice president, took control of the team. Even before his uncle’s death, he had become increasingly anxious about the viability of the team in Washington. The old ballpark had the smallest seating capacity in the league, and the surrounding area was deteriorating, although the new team president tended to blame slumping attendance on the racial makeup of the neighborhood far more than the poor performance on the field. Murphy’s ambition to become majority owner by acquiring the Griffith family stock was rebuffed. Murphy filed several lawsuits to block any move, but those efforts also were ultimately unsuccessful.

Calvin Griffith, already executive vice president, took control of the team. Even before his uncle’s death, he had become increasingly anxious about the viability of the team in Washington. The old ballpark had the smallest seating capacity in the league, and the surrounding area was deteriorating, although the new team president tended to blame slumping attendance on the racial makeup of the neighborhood far more than the poor performance on the field. Murphy’s ambition to become majority owner by acquiring the Griffith family stock was rebuffed. Murphy filed several lawsuits to block any move, but those efforts also were ultimately unsuccessful.

In September 1958, even as financing plans for a new multipurpose stadium were approved by Congress, which controlled the District of Columbia budget, Griffith remained noncommittal about staying in Washington.66 When the site in the Southeast section of the city was chosen for what was to become District of Columbia Stadium, Calvin Griffith said he preferred a location in the far Northwest part of the city, an upscale area with a substantial white population. After winning a May 1959 court challenge by Murphy to his right to leave town, Griffith had stated that “moving the Washington franchise is not my intention.”67

Yet as the 1959 season ended, Calvin formally notified the president of the American Association that the Senators would move to Minneapolis, which had been home to an AA team.68 Griffith soon learned that at least five AL owners would veto any move, however, so he did not seek a formal vote. The Senators would remain in Washington for the 1960 season.

The opposition of other owners was based on several factors. They recognized the value of the tradition Clark Griffith had solidified: having the president of the United States throw out the “first pitch” at the season opening game in Washington. Joe Cronin, by now American League president, obviously had strong ties to the Senators, as did his wife. The most important consideration, however, was the fear that abandoning Washington would prompt Congress to revoke Organized Baseball’s exemption from the antitrust laws.69

That fear was intensified by Branch Rickey’s proposed Continental League, whose eight teams would include one in Minneapolis-St. Paul. Under pressure to expand or face such competition, major-league owners met in October 1960 and decided to add two teams each. The National League, acting first, had given itself until the 1962 season to re-establish its presence in New York and add a team in Houston. American League owners chose to expand sooner and voted on October 26 to add Minneapolis-St. Paul and Los Angeles for the 1961 season. But Minnesota’s Twin Cities would not be saddled with an expansion team. Instead, they would inherit the relocated Senators, giving Calvin Griffith what he had sought the year before. After 60 seasons as one of the charter members of the American League, the original Senators would be replaced in Washington by an expansion team.70

ANDREW SHARP grew up in the D.C. area as a fan of Washington Senators I and II, and spent 30-plus years in the wilderness as a New York Mets fan before happily regaining a Washington team to support. A retired newspaper editor, he began writing BioProject essays in 2017 and has written SABR’s ownership histories of the Griffith era and the expansion Senators. He charts minor-league games on a freelance basis for Baseball Info Solutions.

After the expansion Washington Senators left in 1962, Griffith Stadium was torn down three years later. Howard University Hospital now sits on the site of the old ballpark and the location of home plate is marked inside the hospital entrance with a plaque. (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library)

Notes

1 Shirley Povich, The Washington Senators: An Informal History (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1954), 36.

2 Povich, 37. The 1901 home attendance was 358,692, Povich wrote, but that questionably high figure is cited by no other known source. Attendance figures from the early twentieth century are best viewed with skepticism.

3 Tom Deveaux, The Washington Senators, 1901-1971 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2001), 8.

4 Morris A. Bealle. The Washington Senators: The Story of an Incurable Fandom (Washington, DC: Columbia Publishing Co., 1947), 54.

5 Povich, 275.

6 Deveaux, 9.

7 Deveaux, 10-11.

8 Donald Dewey and Nicholas Acocella, Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball Teams (New York: Harper Collins, 1993), 569.

9 “League to Run Club,” Washington Post, March 9, 1904.

10 Bealle, 60.

11 Steven A. Riess, ed., The Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball Clubs, Volume II: The American League (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2006), 674.

12 Povich, 41.

13 Povich, 42.

14 Bealle, 69.

15 Povich, 43. In contrast, Beale wrote that “the club shopped for the cheapest manager they could find … Cantillon.”

16 Deveaux, 33.

17 Ted Leavengood, Clark Griffith: The Old Fox of Washington Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2011), 90.

18 “Griffith Plans,” Sporting Life, November 25, 1911.

19 “Angus to Retire,” Sporting Life, November 14, 1903.

20 “At the Capital,” Sporting Life, October 12, 1912.

21 Povich, 86-87.

22 Povich, 94.

23 Leavengood put the 1916 attendance at 431,000, while Total Baseball and Baseball-Reference list the 1916 figure as 177,365. During 1917, an attendance of 527 is listed for a game on Thursday, August 5, and for a Saturday doubleheader two days later. This clearly is an underreporting error for the Saturday game, given that all other Saturdays drew crowds of several thousand.

24 Deveaux, 46.

25 “Washington Will Remain an American League Member, Declares Ban Johnson, Denying Franchise Shift Rumors,” Washington Post, December 7, 1918.

26 J.V. Fitz Gerald, “Daylight Saving Measure May Aid Baseball Clubs,” Washington Post, January 18, 1918.

27 “Griffith Sells His Ranch,” Sporting Life, March 3, 1917.

28 Leavengood, 119.

29 Deveaux, 47.

30 Povich, 98.

31 Leavengood, 144.

32Connie Mack managed in a business suit. Earl McNeely, the man who drove in the run that gave Griffith his only world championship, later played for, managed, and briefly owned the Sacramento team in the Pacific Coast League, all in 1934.

33 Leavengood, 139.

34 Henry W. Thomas, Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train (Washington: Phenom Press, 1995), 109.

35 Brad Snyder, Beyond the Shadow of the Senators (New York: Contemporary Books/McGraw Hill, 2003), 11.

36 Snyder, 12-13.

37 Riess, 968. The profit/loss statements of all teams were provided to the US House Subcommittee on the Study of Monopoly Power, 82nd Congress, in 1952 and updated for the Antitrust Subcommittee, 85th Congress, in 1957.

38 Leavengood, 179.

39 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001): 898; Leavengood, 258.

40 Riess, 972.

41 Riess, 968.

42 Riess, 972.

43 Clark Griffith as told to J.G. Taylor Spink, “50 Golden Years in the American League,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1952.

44 Leavengood, 216.

45 Leavengood, 249.

46 Leavengood, 256.

47 Snyder, 70.

48 Povich, “Clark Griffith, 50 Years in Baseball,” Washington Post, February 17, 1938: X19.

49 Thomas, 335.

50 Leavengood, 255.

51 Povich, The Washington Senators, 219.

52 Bealle, 164.

53 Snyder, 94.

54 Snyder, 147.

55 Snyder, 58.

56 Snyder, 75. Snyder discusses at length Sam Lacy’s criticism of Shirley Povich for not pressuring Griffith to integrate his team sooner, although a collection of Povich columns published in 2005, edited by his children, states that Povich advocated integration of the majors in the 1930s.

57 Riess, 968.

58 Riess, 970.

59 Riess, 968.

60 Povich, 229.

61 Povich, 230.

62 Povich, “Jachym Plans to Keep Washington Hot Seat,” The Sporting News, February 8, 1950.

63 Francis Stann, “Griff’s Dislike of Jachym Laid to Praise of Rickey,” The Sporting News, June 28, 1950.

64 Stann, “Griff Gets Silent Partner as Buyer of Jachym Stock,” The Sporting News, June 28, 1950.

65 Lawrence S. Ritter, Lost Ballparks (New York: Viking Penguin, 1992), 88.

66 Dave Brady, “Cal Griffith Non-Committal on New Park,” The Sporting News, July 20, 1960.

67 Povich, “’No Intention to Move Nats,’ Griffith Says,” The Sporting News, June 3, 1959.

68 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Nats Will Shift to Minneapolis, Griff Notifies Doherty and A.A.,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1959.

69 Deveaux, 207.

70 Associated Press, “AL Going Into Los Angeles and Twin Cities in 1961,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 27, 1960.