April 10, 1962: Dodgers lose to Reds in opening game at Dodger Stadium

Walter O’Malley is a bane or a blessing dependent upon which coast the person describing him resides.

In Brooklyn, baseball fans remember O’Malley with contempt for transporting their beloved Dodgers to Los Angeles after the 1957 season. LA baseball fans are proud that O’Malley’s decision not only made the city a major-league metropolis, but also opened the Western region to expansion: Angels in 1961; Padres in 1969; and Mariners in 1977. In the 1990s, the Diamondbacks and Rockies debuted.

While the Dodgers displaced the city’s two Pacific Coast League teams – the Hollywood Stars and Los Angeles Angels (no connection to the American League squad) – they needed a major-league ballpark of their own. From 1958 to 1961, they played in Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

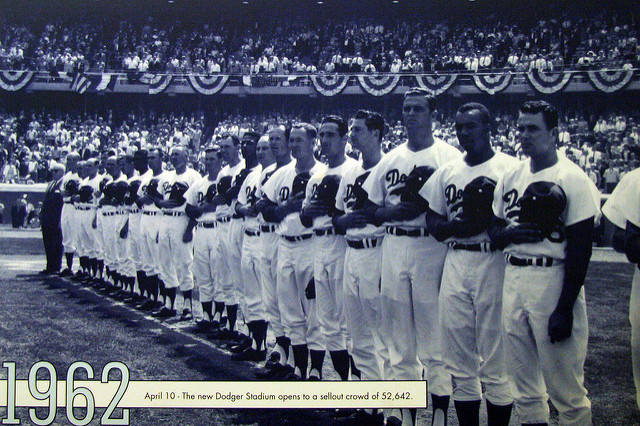

In 1962 O’Malley unveiled his vision for a modern ballpark befitting the fans who immediately embraced Dodger Blue as their favorite color in the spectrum. Dodger Stadium debuted on April 10, ushering in a new era for Southern California baseball. But it began on somewhat of a sour note: The Dodgers lost the Opening Day game to the ’61 NL champion Reds. Score: 6-3.

This new edifice eclipsed the stadiums built in days of yore because of design, comfort, and luxury commanding respect, excitement, and awe.

Sportswriting legend Jack Murphy wrote, “Never has the game of rounders been played amid such splendor. The Dodgers new park is so plush that I wouldn’t dare remove my coat or loosen my tie while writing this essay; surely an usher would evict me immediately.”1

Johnny Podres had the honor of being the Dodgers’ first starting pitcher in the new ballyard, which drew 52,564 fans on this special day. They sat in seats with muted colors of yellow, orange, turquoise, and blue. With the increasing use of color television, Dodger Stadium would be a visual lure for TV viewers. Groundskeepers had painted the grass green.2

The home team faced a 1-0 deficit in the top of the first. Vada Pinson got the first RBI off the southpaw, scoring Cincinnati’s leadoff batter Eddie Kasko, who had smacked a double and taken third base on Cookie Rojas’s sacrifice.

LA responded with two runs in the bottom of the fourth, courtesy of Ron Fairly’s two-run double, scoring Jim Gilliam and Duke Snider. Gilliam had begun with a single and moved to second base on Wally Moon’s grounder to second baseman Rojas. Snider’s infield single gave Gilliam a path to third base, putting runners at the corners. After John Roseboro grounded out and gave Snider the opportunity to take second, Fairly’s swat gave Dodgers fans something to cheer about in their new ballpark.

The Reds evened the score in the top of the sixth. Pinson led off with a walk followed by two outs, Frank Robinson’s foul out to Fairly at first base and Wally Post’s fly ball to Willie Davis in center. Gordy Coleman’s single gave Pinson second base; Tommy Harper’s single to Dodgers stalwart Snider in right field scored him and pushed Coleman to third. Harper extended his journey to second base when Snider fired the ball.3 Podres loaded the bases with an intentional walk of Johnny Edwards to face Reds hurler Bob Purkey. The strategy proved valid. Purkey struck out.

When the Reds came up next, they added three runs. Podres got two outs on Kasko’s grounder to third baseman Daryl Spencer and Rojas’s fly to Moon in left. Then Cincinnati commenced a two-out rally. Pinson doubled; Robinson got an intentional walk; and Post smashed a three-run homer.

Alston admitted that his strategy of walking Robinson came from apprehension of his prowess. “Well, Robinson has always been a thorn in our side,” explained the Dodgers manager, beginning the ninth of 23 seasons at the helm. He was the league’s Most Valuable Player last year and you know he got a hit the next time he came up.”4

Podres retired Coleman on a fly out to Davis, sending the Dodgers to bat with a 5-2 gap.

Walter Alston changed pitchers in the top of the eighth, after Podres gave up singles to Harper and Purkey. Larry Sherry came into the game with one out, then retired Kasko on a fly ball and pinch-hitter Jerry Lynch on a called third strike.

When Dodger Stadium’s new occupants loaded the bases in the bottom of the eighth, Cincinnati changed pitchers.

Purkey had gotten Tim Harkness – pinch-hitting for Sherry – out on a grounder to Harper. Maury Wills drew a walk, which was never good for opposing NL squads in ’62. He broke Ty Cobb’s stolen-base record of 96 in a single season with 104 thieveries. Here, he stayed in the vicinity of first base until Gilliam’s single sent him to second and Moon’s walk advanced him to third.

Cincinnati left-hander Bill Henry came in from the Reds bullpen and faced Tommy Davis pinch-hitting for Snider. To the frustration of fans from Moorpark to Mission Viejo, Davis grounded to Kasko for a double play.

The Reds amplified their lead with a sixth run in the top of the ninth. Ron Perranoski relieved Sherry. (LA’s ace reliever led the majors with appearances in 70 games that season.) Pinson and Robinson hit back-to-back singles; Pinson scored on flies by Post and Coleman to center field.

Cincy’s offense shone brighter than klieg lights at a Hollywood premiere. Pinson had a 4-for-4 day with three runs scored, a walk, and an RBI. Post went 3-for-5; Harper also notched three hits.

What made the victory more splendid than usual was the lack of rest for the victors. According to Lou Smith of the Cincinnati Enquirer, “less than five hours of sleep” graced the visiting squad, a result of an extended plane flight lasting more than nine hours and a 4:00 A.M. arrival in Los Angeles. Smith wrote that “strong headwinds” caused the expanded length.5

It was Podres’ first loss on his journey to a 15-13 record in 1962.

Besides his team’s inaugural loss, O’Malley faced some glitches with elevators and parking. With parking-lot sections exceeding 50, chaos emerged. “The opening day crowd had all kinds of trouble determining where their parking areas were located – and even the attendants often were confused in giving directions,” explained reporter Hank Hollingworth. “One Long Beach party wasted one hour after reaching the parking lot entrance before landing in the proper parking section.”6

Elite fans and the press had access to two elevators. One went kaput in the middle of the game. But an array of 10 buttons made the job of the operators confusing at best for the other elevator.7

Traffic was predicted to be a hassle. It wasn’t. A highly significant factor was the buildup of a perceived crisis that inspired fans to jaunt to the ballpark as early as 9:30 A.M. for a 1:00 P.M. start. LAPD Chief William H. Parker said, “We expected this to be one of the biggest traffic problems we have had to face.”8

Los Angeles Times reporter Paul B. Zimmerman observed that the parking lots were empty within a half-hour after the game ended.9

But the new ballpark in Chavez Ravine did not have a smooth path toward completion. Indeed, O’Malley had to navigate challenges in the political, social, and public relations. In his book Stealing Home: Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between, SABR 2021 Seymour Medal winner Eric Nusbaum tackles the complexities involving Hispanic families living in Chavez Ravine balanced against the civic goals of a baseball hallmark. Public housing vs. public relations. Nusbaum writes of O’Malley: “[H]e was acquiring the hangover from the war over public housing that had made this land available in the first place.”10

Dodger Nation had an aura of excitement in ’62. In addition to Dodger Stadium setting a new standard for ballparks and Wills’s exemplary performance on NL basepaths, Don Drysdale went 25-9 and won the Cy Young Award. The Dodgers tied the Giants for the NL title, then lost two out of three in a playoff. The Yankees defeated the Giants in seven games to win the World Series.

Acknowledgments

This article was copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes below, the author relied on pertinent information from Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org, including the box scores.

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1962/B04100LAN1962.htm

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/LAN/LAN196204100.shtml

Notes

1 Jack Murphy, “Park Lights Glow, Starlights Dim at New Dodger Stadium,” Monrovia (California) Daily News-Post, April 11, 1962: 4.

2 George Lederer, “Daffy Day At Chavez (?) Ravine,” Long Beach (California) Independent, April 11, 1962: C-2.

3 Retrosheet’s account does not say if Snider threw the ball home or to third base.

4 Associated Press, “Wally Moon Sums It Up: Good Game, Wrong Finish,” San Bernardino Daily Sun, April 11, 1962: 8. Robinson led the National League in slugging percentage from 1960 through 1962. For two of those years, he led the majors.

5 Lou Smith, “Dodgers’ New Stadium Utmost in All Respects,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 11, 1962: 23.

6 Hank Hollingworth, “Dodger Fans Find Parking, Not Traffic, Is Headache.” Long Beach Independent, April 11, 1962: 1.

7 “Dodger Fans Find Parking, Not Traffic, Is Headache.”

8 Paul Zimmerman, “Stadium Opener Lost by Dodgers,” Los Angeles Times, April 11, 1962: 1.

9 “Stadium Opener Lost By Dodgers.”

10 Eric Nusbaum, Stealing Home: Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between (New York: Public Affairs, 2020), 279.

Additional Stats

Cincinnati Reds 6

Los Angeles Dodgers 3

Dodger Stadium

Los Angeles, CA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.