April 14, 1936: Boston Bees make their debut on Opening Day

The 1935 edition of the Boston Braves weren’t just bad, they were historically bad. Many people credit the hapless 1962 New York Mets as being the worst team of the modern era with their 40-120 record, but the 1935 Braves actually finished with a slightly worse won-lost percentage than that Mets squad (.250 for the Mets, .248 for the Braves with a 38-115 record). When a team does that bad in a season it isn’t uncommon for an overhaul to follow, both of the front office and the players. But the Braves took the renovating a step further — they completely changed their identity.

The 1935 edition of the Boston Braves weren’t just bad, they were historically bad. Many people credit the hapless 1962 New York Mets as being the worst team of the modern era with their 40-120 record, but the 1935 Braves actually finished with a slightly worse won-lost percentage than that Mets squad (.250 for the Mets, .248 for the Braves with a 38-115 record). When a team does that bad in a season it isn’t uncommon for an overhaul to follow, both of the front office and the players. But the Braves took the renovating a step further — they completely changed their identity.

From the outset of the 1935 season the Boston Braves were in financial turmoil. Looking for any way to bring in additional revenue, team President and primary stockholder Judge Emil Fuchs even signed Babe Ruth to play for the Braves and draw in a crowd. The move paid off at first, with fans coming out in droves to see Ruth’s return to Boston, but after the initial excitement it became obvious that Ruth was well past his prime, and after 28 games in a Braves uniform he quit.

On August 1, with all hope of lifting the Braves out of debt gone, Fuchs handed in his resignation and his shares of the team’s stock, and the Braves were on the search for a new owner.1 As of late November the Braves ownership situation had not been settled and the National League was forced to step in and take control of the team.2 On December 10 the NL office brought in longtime baseball executive Bob Quinn to run the franchise as its new president,3 and he went to work immediately on a rebuild. Between his hiring in December and Opening Day, Quinn made eight deals with that involved 15 players. Despite all the changes in the office and in the lineup, manager Bill McKechnie kept his role and returned as skipper for the coming season.

The changes in team personnel were just a portion of the Boston’s offseason makeover. In January 1936 the club announced that it was no longer to be referred to as the Braves and held a contest for fans to suggest a new moniker.4 The name of their home ballpark was changed from Braves Field to National League Field. And though they were still without an official nickname, the team’s colors were changed from their traditional navy and red to royal blue with gold trim.

On January 30 it was announced that the new team name was the Bees. The name was chosen out of over 1,300 submissions, beating out Blue Birds, Colonials, and Blues, among others.5 Sportswriters pondered if the home field should now be referred to in articles as the “beehive” instead of the “wigwam.”6 Boston headed to spring training in February with hopes that a revamped lineup, along with the new persona, would help erase memories of the previous year and pull the team out of the National League cellar.

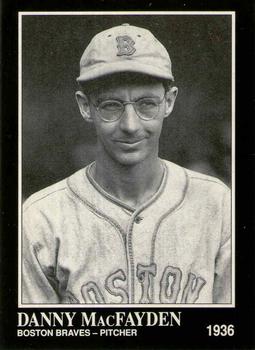

The Bees opened the 1936 season on April 14 with a visit to Philadelphia for an afternoon game. Only 9,000 fans came to the Baker Bowl to see the Phillies and Bees — the two cellar dwellers of the National League. Curt Davis was scheduled to make the Opening Day start for the Phillies for the second year in a row. The Bees sent Danny MacFayden to the mound for the third Opening Day start of his career. (The previous two had been with the Red Sox in 1930 and 1932.)

The festivities for the day began at 1:00 P.M. with a performance by the United States Marine Reserve Corps band, followed by the traditional parade of the teams to the flagpole. The Phillies emerged from the dugouts in their red, white, and blue home uniforms, and the Bees sported their new road grays, featuring blue caps and stirrups. They represented Boston with the city name across their chest in blue and gold, and a gold “B” on their hats. A pregame ceremony paid tribute to catcher-manager Jimmie Wilson, coach Hans Lobert, outfielder Ethan Allen, pitcher Syl Johnson, and former pitcher Al Maul for their years of service to Philadelphia baseball. Philadelphia Mayor S. Davis Wilson fired a strike to Wilson for the first pitch, and the Phillies took the field to begin the game.

The teams exchanged scoreless frames for the first two innings, but MacFayden ran into trouble in the bottom of the third. Third baseman Johnny Vergez led off with a single and went to second on Leo Norris’s sacrifice. Davis helped his own cause by driving a single back up the middle that plated Vergez with the first run of the game. Next Ethan Allen tapped a slow roller that was headed between the pitcher’s mound and first base. MacFayden broke toward the ball, but backed off to let second baseman Tony Cuccinello take it, except that Cuccinello had seen MacFayden moving in and he too had slowed down. Cuccinello finally charged in and fielded the ball but Allen narrowly beat the throw to first.

George Watkins grounded out for the second out as the runners moved up a base. With runners now on second and third, Johnny Moore hit a high chopper that bounced up toward second base. Cuccinello ran in to make a play, but when he looked up he was blinded and turned his back to the sun, and the ball bounced past him into shallow right field. Both runners had been on the move with two outs and both scored on the play. The Phils scored once more in the inning when Dolph Camilli doubled to score Moore from first, putting the Bees in a four-run hole. These were the only runs Philadelphia mustered during the game, but it was all they needed.

Davis had defeated Boston five times in a row going back to the 1934 season, and he picked up right where he left off. After walking leadoff batter Gene Moore to start the game, Davis quickly settled in and cruised through seven shutout innings before giving up a run in the eighth. Cuccinello led off that inning with a walk, then went to third base on a single by former Phillie Hal Lee, one of his two hits in the game. Al Lopez followed with a grounder to shortstop Norris, and the Phillies ceded the run in order to complete a 6-4-3 double play. This run accounted for all of Boston’s scoring in the game.

Davis allowed eight baserunners. (Pinky Whitney was hit by a pitch, and then four singles and three walks), and other than Cuccinello no other Bees got past second base. The final score didn’t reflect it, but MacFayden also pitched a solid game. Outside of the rough third inning, he only gave up two singles and a walk before being relieved by Wayne Osborne for the eighth inning.

The Phillies made things interesting in the eighth by loading the bases on a single and two walks, but Osborne closed out the inning without any scoring. In the top of the ninth inning Boston made one last effort to get back in the game. The Bees placed runners on first and second with one out after a single and a walk, but Wally Berger popped out to first base and Cuccinello flied out to right field for the final out. Curt Davis earned the complete-game victory, his sixth in a row over Boston, and he tacked on a hit and an RBI for good measure.

The inaugural Boston Bees season started off rough, but by the end of the year they were a much-improved ballclub. They finished 1936 with a record of 71-83, nearly doubling their win total from the previous year and bumping them up two notches in the NL standings to sixth place, ahead of Brooklyn and Philadelphia.

Boston played for four more seasons as the Bees, but the new name never seemed to catch on, and it certainly never helped them climb out of the second division. In April 1941 Quinn was able to bring in a new group of stockholders to share in the ownership of the club.7 At the first meeting of the new owners, on April 29, one of the items on the agenda was to officially change the team name back to the Braves.8 The team had already dropped the royal blue and gold colors and transitioned back to navy and red a couple of years earlier, and they never did display “Bees” anywhere on the uniforms, a sign that maybe Boston fans were not taking to the new team identity and that a change back to the old name was only a matter of time.

Sources

Caruso, Gary. The Braves Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995).

Coen, Ed. “Setting the Record Straight on Major League Team Nicknames,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2019: 69-70.

Costello, Rory. “Bob Quinn,” SABR BioProject.

LeMoine, Bob. “Judge Emil Fuchs,” SABR BioProject.

The author used baseball-reference.com for play-by-play information and box score (baseball-reference.com/boxes/PHI/PHI193604140.shtml).

newspapers.com was used to research articles from the Boston Globe (1935-1941).

Notes

1 Melville E. Webb Jr., “Club Still to Be Sold,” Boston Globe, August 1, 1935: 18.

2 Hy Hurwitz, “National League Takes Over Braves,” Boston Globe, November 27, 1935: 1.

3 “Bob Quinn Has Taken Over Braves,” Boston Globe, December 11, 1935: 20.

4 James C. O’Leary, “’Braves’ Drop Old Nickname,” Boston Globe, January 4, 1936: 1.

5 “Braves Are to Be Called the ‘Bees,’” Boston Globe, January 31, 1936: 23.

6 “Live Tips and Topics,” Boston Globe, January 31, 1936: 24.

7 Melville E. Webb Jr., “New Englanders Hold Bees Now,” Boston Globe, April 21, 1941: 10.

8 “Bees No More, It’s the Braves,” Boston Globe, April 30, 1941: 20.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Phillies 4

Boston Bees 1

Baker Bowl

Philadelphia, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.