April 19, 1890: Rochester registers its first win in American Association

“We shall surprise a good many people this summer,” Rochester manager Pat Powers shared with Sporting Life reporter W.L. Harris on the eve of the American Association’s 1890 season.1 New to the Association, the team incorporated as the “Rochesters Limited” had already shocked the National League’s New York Giants, defeating the reigning World’s Series champions in a pair of preseason matches at the Polo Grounds.2 After close losses in its first two games of the season, Rochester engineered a come-from-behind win on April 19 for its first major-league triumph, secured by the strong right arm of left fielder Harry Lyons.

“We shall surprise a good many people this summer,” Rochester manager Pat Powers shared with Sporting Life reporter W.L. Harris on the eve of the American Association’s 1890 season.1 New to the Association, the team incorporated as the “Rochesters Limited” had already shocked the National League’s New York Giants, defeating the reigning World’s Series champions in a pair of preseason matches at the Polo Grounds.2 After close losses in its first two games of the season, Rochester engineered a come-from-behind win on April 19 for its first major-league triumph, secured by the strong right arm of left fielder Harry Lyons.

Before joining the Association, Rochester had competed in the International League, where, known as the Jingoes, they’d enjoyed first-division finishes the previous two years. After Brooklyn, Cincinnati, and Kansas City abandoned the Association for greener pastures in November 1889, Rochester was added, along with teams from Syracuse and Toledo.3

During the winter of 1889-90, the new Players’ League cast a long shadow on both the Association and the League, as the NL was then called. Formed by the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players, the PL strategically placed teams in many of the same cities where the two established leagues already had franchises and signed away many of their talented players by offering higher pay and more ballplayer-friendly policies.4

Coming up from a lower-level league, Rochester drew little attention from PL raiders. Nonetheless, Powers beefed up the roster of the Jingoes team he’d managed the year before with a handful of seemingly flawed players. He added Bill Greenwood, a left-handed-throwing journeyman second baseman; Deacon McGuire, a weak-hitting backup catcher on the brink of stardom; and Lyons, an outfielder with the reputation of being a clever fielder despite fielding stats to the contrary.5

Rochester opened its inaugural Association season in Philadelphia. The Association Athletics were decimated by PL personnel raids. Gone from a team that had finished third in each of the previous two seasons were its three top run-producers – Harry Stovey, Henry Larkin, and Lou Bierbauer – plus swift-pitching ace Gus Weyhing. Owner-manager Bill Sharsig had to lean heavily on a primary battery of 22-year-old hurler Sadie McMahon and catcher Wilbert Robinson and a lineup otherwise filled with reclamation projects. To replace Stovey and Larkin, Sharsig installed a pair of aging veteran corner outfielders: 36-year-old Blondie Purcell, a flaxen-haired former two-way player; and 38-year-old Orator Shafer, a four-time NL assists leader and major-league single-season assist record holder.6

Thankfully, the Blue Legs, as the Association nine were known after their dark blue stockings,7 had Philadelphia all to themselves for their season-opening, four-game series with Rochester. The City of Brotherly Love’s PL nine as well as the NL’s Phillies, were opening their seasons in New York.

Rochester dropped the season opener at Jefferson Street Grounds by a score of 11-8, leaving the bases loaded when their last batter, McGuire, flied out to left in the bottom of the ninth.8 The Philadelphia Inquirer called both teams nervous, with pitchers so wild they seemed “afflicted with St. Vitus’ dance.”9 The second game produced a similar result. Rochester lost 12-9 after the Athletics scored five unanswered runs in the last two innings.10

Hopeful of bringing Flower City its first major-league victory, Powers sent hurler Bob Barr out for the third game. The Jingoes’ ace the previous two years, winning an International League-leading 30 games in 1889 and 35 the year before, Barr had experienced little success during three previous seasons in the majors. He entered 1890 with a career ERA+ of 76 and a .231 won-lost percentage (21-70), the lowest of any major-league hurler with 40 or more lifetime decisions. Regardless, Powers expected great things of Barr in the new season, declaring beforehand that “Barr never had greater speed and he has a slow ball this season that will fool the best of them.”11 Starting opposite Barr was Philadelphia’s Opening Day starter, McMahon. In that meeting, he’d been hit hard but came away victorious.

As they’d done in the two previous games, the Athletics elected to bat first in the third game, played in front of a crowd of 2,106 on a pleasant but chilly (52-degree high) Saturday afternoon.12 The home team broke the ice in the top of the second on a two-out RBI single by Orator’s 23-year-old brother, Taylor.13 Rochester knotted the score in the third. McGuire singled with one out, advanced to second when Purcell in left field couldn’t field the ball cleanly, reached third on Robinson’s passed ball and scored when Barr flied out on a ball that carried to the fence in left field.

Philadelphia recaptured the lead in the fifth on a “corker down the left field line” by Purcell that went for two bases,14 followed by singles from a pair of Sharsig’s scrap-heapers: Slugger Jack O’Brien,15 a former Athletic coaxed out of semi-retirement, and Joe Kappel, who’d bounced around lower-level leagues since playing a handful of games with the 1884 Phillies.

An inning later, Rochester erased the Athletics’ lead once again. With one out in the sixth, speedy Ted Scheffler singled, stole second,16 advanced to third on an errant pickoff attempt by Robinson and scored when shortstop Ed Carfrey, making his lone major-league appearance,17 fumbled a grounder hit by Lyons. The score stood tied at 2-2.

Rochester pulled ahead for the first time in the seventh on a rally that began when 21-year-old rookie Will Calihan banged a double off the outfield fence. Rochester’s Opening Day starting pitcher, Calihan had entered this game in the second inning after center fielder Sandy Griffin broke his left foot sliding into second base.18 Calihan came home on a single pulled to right by the switch-hitting Greenwood.

With neither side able to push a run across in the eighth, the score remained 3-2 in favor of Rochester entering the ninth. Curt Welch, the everyday center fielder on the St. Louis Browns team that dominated the Association from 1885 to 1887, hit a one-out double to left. Purcell lifted a popup to left that Lyons “after a desperate run captured, the momentum nearly upsetting him.”19 A Philadelphia fan favorite who hailed from nearby Chester, Pennsylvania, Lyons drew applause from the appreciative crowd for the play.20

Down to their last out, Philadelphia’s hopes rested on the shoulders of their hard-hitting third baseman, Denny Lyons. The Athletics’ best hitter in 1890, he finished the year batting .354 and led the Association in slugging percentage (.531), OPS (.992), and OPS+ (193).21 Three years earlier, Denny had compiled a then-record 52-game hitting streak that decades later was reclassified as a consecutive on-base streak.22

Hitless in his previous at-bats, Lyons drove a Barr offering into left for a hit. Welch raced for third, then ran through a stop sign put up by Robinson, who was standing “in the coacher’s box.”23 As Welch headed for home with the tying run, Harry Lyons unleashed a “beautiful throw” to the plate.24

Expecting a close play, Welch dropped into a slide. Four years earlier, he’d scored the winning run in the deciding Game Six of the 1886 World’s Championship series (on a wild pitch) with what was dubbed the “$15,000 slide.” This time, he was denied. McGuire tagged Welch, who was called out by rookie umpire Bob Emslie, later to become “the least-known famous umpire in baseball history,”25 and the game was over. Harry Lyons, the son of a Philadelphia policeman, had spectacularly robbed his namesake of a chance to tie the game.26

“It is difficult to tell whether the credit for Rochester’s victory belongs to Harry Lyons, Calihan or Barr,” the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle declared, adding that the “trio combined went far toward winning the game.”27 The Philadelphia Times claimed “bad coaching” cost the Athletics a chance to tie the game in the ninth, but rated the contest “close and exciting throughout.”28

The victory launched an eight-game winning streak for Rochester that propelled the team to the top of the Association standings. Philadelphia overtook them in late May and held onto first place for nearly two months. After financial troubles led the club to start shorting ballplayers their pay in July, the Athletics went into a tailspin.29 They lost their last 22 games and finished in eighth place, ahead of only the disbanded Brooklyn Gladiators. Bankrupt and “in arrears in unpaid salaries, league dues and gate guarantees,” they were expelled from the Association after the season.30

While Rochester had been successful on the field, finishing at .500 and in fifth place, they too suffered withering financial losses, roughly $18,000. Eager to place franchises in cities much larger than Rochester, Association leadership persuaded principal owner-president Henry Brinker to relinquish his franchise for $10,000.31

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kurt Blumenau and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the Baseball-Almanac.com Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Stathead.com websites.

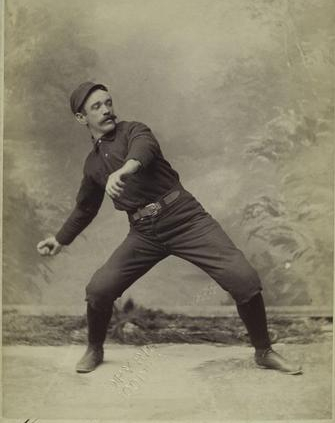

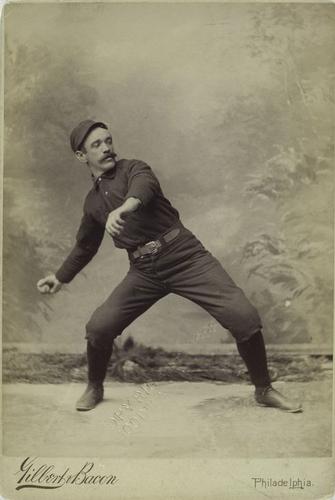

Photo credit: Deacon McGuire, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 W.L. Harris, “Happy Pat Powers,” Sporting Life, April 19, 1890: 13.

2 M.T.S., “Rochester Ripples,” Sporting Life, April 12, 1890: 3; “Rochester Ripples,” Sporting Life, April 19, 1890: 10.

3 John Bauer, “1889-90 Winter Meetings – The Establishment Responds,” in Baseball’s 19th Century Winter Meetings: 1857-1900 (Phoenix: SABR, 2018), 271.

4 For a detailed discussion of the Players’ League, see Robert Ross, The Great Baseball Revolt: The Rise and Fall of the 1890 Players’ League (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press: 2016).

5 “Grand Stand Chat,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 21, 1888: 8. In what was his only previous year as a major-league regular, Lyons led all Association outfielders with 33 errors.

6 Shafer’s 50 outfield assists for the 1879 Chicago White Stockings has, through the 2024 season, never been equaled.

7 “Sharzig’s [sic] “Blue Legs” on Top, Harrisburg Telegraph, April 12, 1890: 1; “1890 Athletic, Philadelphia (Athletics),” Thread of Our Game website, https://www.threadsofourgame.com/1890-athletic-philadelphia/, accessed September 22, 2024.

8 “One for the Athletics,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 18, 1890: 6.

9 “One for the Athletics.” A term dating back to the Middle Ages, “St. Vitus’s dance” refers to irregular and involuntary movements in various muscle groups that can stem from streptococcal infection – a condition now known as Sydenham Chorea. “Sydenham chorea,” Britannica.com website, https://www.britannica.com/science/Sydenham-chorea, accessed October 26, 2024.

10 “Two for the Athletics,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 19, 1890: 6.

11 “Happy Pat Powers.”

12 “Barr, Lyons and Calihan,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 20, 1890: 7; “The Weather,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 20, 1890: 1.

13 “Barr, Lyons and Calihan.” Born in July 1866, Taylor was nearly 14 years and 9 months younger than Orator. As of September 21, 2024, Baseball-Almanac.com listed 454 sets of siblings who played major-league baseball. The author has identified only six other sets of brothers on that list who were further apart in age than the Shafers: Art and Jesse Fowler (23 years, 8 months), Pat and Ham Patterson (19y, 3m), Heinie and Frank Manush (17y, 10m), Bill and Pat Friel (17y, 10m), Bob and Ike “Newt” Fisher (15y, 4m), and Jim and John Paciorek (15y, 4m). “Baseball Brothers,” Baseball-Almanac.com, https://www.baseball-almanac.com/family/fam1.shtml, accessed September 21, 2024.

14 “Barr, Lyons and Calihan.”

15 “Rochester Calls a Halt.”

16 The theft was Scheffler’s second of 77 steals for the year, second only in the Association to Tommy McCarthy, who stole 83 for the St. Louis Browns.

17 Caffrey was filling in for Dennis Fitzgerald, who’d severely wrenched his ankle the day before in what was his first game in the majors. Yet another Philadelphia shortstop made his major-league debut the day after this game, Ben Conroy, who earned the most playing time of the nine shortstops the Athletics used in 1890. “Two for the Athletics.”

18 “Rochester Calls a Halt.”

19 “Barr, Lyons and Calihan.”

20 “The Browns Beaten,” St. Louis-Post Dispatch, May 30, 1888: 2; “Lyons Saved the Game,” Philadelphia Times, April 20, 1890: 3.

21 All three figures are retrospective; they were not compiled in that era.

22 Matthias Koster, “Denny Lyons 52 Game Hit Streak,” Mop-Up Duty website, December 10, 2010, https://mopupduty.com/denny-lyons-52-game-hit-streak/. In two of those games, Lyons’ only “hit” came via a base on balls, which in 1887 were counted as hits. One of major league baseball’s many rule changes in 1968 reclassified 1887 walks as no longer hits.

23 “Rochester Calls a Halt.”

24 “Barr, Lyons and Calihan.”

25 Considered by many of his peers to have been “the greatest base umpire of all time,” Emslie, a pitcher for the 1885 Athletics, is best known for a call he didn’t make. Manning the bases in a late-September game between the New York Giants and Chicago Cubs during the 1908 NL pennant race, he failed to notice whether New York’s Fred Merkle had touched second on an apparent game-ending single, after which home plate umpire Hank O’Day famously waved off the winning run; a play known to history as Merkle’s Boner. David Cicotello, “Bob Emslie,” SABR Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bob-emslie/. Accessed October 3, 2024.

26 “Notes,” Wilmington (Delaware) Every Evening, August 24, 1887: 4;

27 “Barr, Lyons and Calihan.”

28 “Lyons Saved the Game.”

29 Cliff Blau, “The 1890 Athletics: The Worst Team in Major League Baseball History,” Seamheads website, October 9, 2012, https://seamheads.com/blog/2012/10/09/the-1890-athletics-the-worst-team-in-major-league-baseball-history/. Author David Nemec in his The Beer and Whisky League attributes Philadelphia’s collapse to a spate of injuries suffered by Dennis Lyons, “real or imagined,” poor pitching by everyone other than Sadie McMahon and a lack of offense from their middle infielders. David Nemec, The Beer and Whiskey League (New York: Lyons and Burford, 2004), 195.

30 John Bauer, “1890 – Three Divides into Two,” in Baseball’s 19th Century Winter Meetings: 1857-1900 (Phoenix: SABR, 2018), 293.

31 Bauer, “1890 – Three Divides into Two,” 294. Rochester’s population in 1890, according to the 1890 U.S. Census, 5,321, was tiny compared to two of the preferred cities, Chicago (1.1 million) and Boston (448,000).

Additional Stats

Rochester Hop Bitters/Broncos 3

Philadelphia Athletics 2

Jefferson Street Grounds

Philadelphia, PA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.