Gus Weyhing

“Gus Weyhing is one of the swiftest pitchers in the business. He is, comparatively speaking, a small man and his appearance gives no indication of the muscular power necessary to manipulate the ball at the speed with which he delivers it.”1

“Gus Weyhing is one of the swiftest pitchers in the business. He is, comparatively speaking, a small man and his appearance gives no indication of the muscular power necessary to manipulate the ball at the speed with which he delivers it.”1

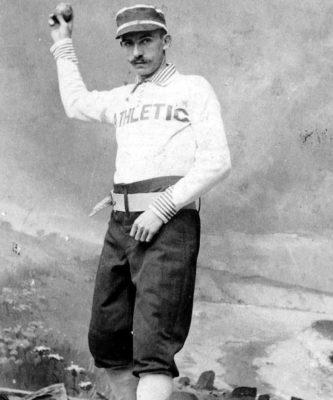

The 145-pound Weyhing was a true rabble rouser, often as mischievous off the field as he was wild in the pitcher’s box. The mustachioed twirler put together a career that might appear Hall of Fame-worthy at first blush, considering his lofty win total (264) and innings pitched (4,337). His legacy, however, is as the all-time major league leader in hit batsmen with 277, a record that has remained unassailed since Weyhing last plunked a batter in 1901.

August (“Gus”) Weyhing was born on September 29, 1866, in Louisville, Kentucky, the second youngest of six children.2 His parents, Adam Weyhing (saloonkeeper) and Katherine (née Bubenhoffer, homemaker), had immigrated from Württemberg, Germany.3 At fifteen, Weyhing lived with his family at 431 Chestnut Street in Louisville, and was employed as a house painter.4 Weyhing’s younger brother John (11)—also a future major league pitcher—was a store clerk.5 His mother, Katherine, was widowed.

Gus Weyhing’s formative baseball career began in 1885, as a right-handed pitcher for the Henley company team in Richmond, Indiana. Micajah Henley manufactured sports equipment and had patented the flip-up stadium seat.6 Weyhing pitched well and it was front page news when he struck out 17 Cambridge City batters on September 25.7 On September 30, his team played for the Indiana State Championship against that same Cambridge City club.8 Tied 2-2 after nine innings, Richmond took the lead, 3-2, in the top of the tenth, to “men and women and children waving hats and handkerchiefs and ballooing at the top of their voices.”9 Weyhing struck out the first two batters he faced in the bottom of the tenth. Unfortunately—just one out away from the championship—he hit a batter in the ribs, then allowed an infield single and a walk-off, three-run home run.10 Despite the disappointing end to the season, Weyhing finished the 1885 campaign with a 19-3 record and several offers to join the professional ranks.11

In January 1886 Weyhing reportedly signed with Atlanta in the Southern League in a deal that would pay him $125 (approximately $3,600 today) per month.12 Less than a week later, however, he instead signed with the Charleston Seagulls, along with his Henley batterymate Charley Williams.13 Weyhing quickly won over the fans in Charleston and was presented with a gold watch and chain by his local admirers during the game on April 24.14 By May, Weyhing was ballyhooed as “the greatest pitcher in the Southern League…regarded as the equal of Toad] Ramsey” (who had posted an 0.89 ERA over 354 IP for the 1885 Chattanooga Lookouts).15 Soon after, he drew interest from the Philadelphia Athletics, though the Philadelphia Times did not predict he would find much success in the American Association.16 On July 14, Weyhing tossed his final game for Charleston, with Memphis “knocking Weyhing completely out of the box.”17 It was widely rumored that he had quit after having strained his arm, an injury that caused his muscles to form an “unnatural lump on his back.”18 Despite the ignominious end to his first professional campaign, Weyhing posted a 13-18 record that belied a microscopic 0.76 ERA across 32 starts. His 25 hit batsmen and 43 wild pitches presaged a career that would be defined by wildness—in more ways than one.

Weyhing signed with the National League Philadelphia Quakers before the 1887 season and worked out in the month before heading east from Louisville with Joe Crotty, a light-hitting catcher who had seen his last big league action in 1886 with the New York Metropolitans. Crotty expected Weyhing would be one of the best pitchers in the National League: “[H]e has good command of the ball and plenty of speed.”19 On April 9, Weyhing made his first appearance in an exhibition game between the Quakers and American Association Philadelphia Athletics, tossing a pair of scoreless relief innings.20 He started a game on April 10, but was pulled after allowing 11 runs (seven earned) in five innings.21 The Quakers released him before the regular season began and he was quickly scooped up by the crosstown Athletics.22 He made his debut for the Athletics on May 2, an “effective” performance in which he recorded his first major league win and hit against the Brooklyn Grays. Three days later he was tagged for the loss against the Baltimore Orioles in a “dull and uninteresting” affair in which he was simply described as “wild.”23 Amid the ennui, Weyhing plunked third baseman James “Jumbo” Davis, the first in his record-setting career.24

On July 16 Weyhing drew the start at St. Louis. He pitched well, unfazed by a runaway team of horses that galloped onto the field at the end of the third inning. Browns first baseman Charles Comiskey was “liberally rewarded by cheers and applause” after he daringly captured the horses and saved the carriage.25 Weyhing complained of a sore arm after six innings and was pulled. He missed just a few starts and returned the field on July 26, a 3-2 victory at Cincinnati. Another 29 starts brought his rookie season total to 55, 53 of which were complete games. He ended the season 26-28, with a 4.27 ERA in 466 1/3 innings pitched. His lack of command was evident—he led the major leagues with 37 hit batsmen to set the rookie record and finished third with 49 wild pitches.26

In 1888 Weyhing was back with the Athletics, who had also signed Gus’s nineteen-year-old brother John, a southpaw hurler.27 John Weyhing never appeared for Philadelphia, however, and was signed by the American Association Cincinnati Red Stockings after his release in July.28 It was at Cincinnati on July 6 that Gus Weyhing and the Athletics threw an epic temper tantrum described as “the most disreputable conduct ever witnessed at the Cincinnati Ball Park.”29 Mayor Amor Smith Jr. left the ballpark in an outrage over the profanity used by the Athletics in protesting the safe call on a Bid McPhee stolen base. Weyhing later walked off the field, refusing to continue, which resulted in a hefty $200 fine. Umpire Herm Doescher was so disgusted he formally resigned after the chaotic contest.30

Weyhing tossed a shutout at Brooklyn on April 28 in which his no-hitter was broken up with two outs in the ninth.31 He was able to complete the job on July 31, however, when he tossed a no-hitter against the Cowboys in Kansas City. The only two Cowboys to reach base were on a walk and a hit by pitch. Two Kansas City runners having been caught stealing at second base, however, meant that Weyhing faced the minimum. Gus was just as electric at the plate, legging out a double and triple as the Athletics won, 4-0.32 Dispelling any notion of a sophomore jinx, Weyhing compiled a 28-18 record in 47 starts and drastically shrunk his ERA to 2.25. His success was not necessarily tied to harnessing his command, however, as he led the league with 56 wild pitches and a record-setting 42 HBP.33 He married Mollie (maiden name unknown) on November 12 in Jeffersonville, Indiana, just across the Ohio River from Louisville.34

With the Athletics in 1889, Weyhing made 53 starts and posted a 30-21 record with a 2.95 ERA, the first of four consecutive years in which he would win at least 30 games. He was a little less wild, finishing second with 34 hit batsmen and tied for second with 37 wild pitches. In December he jumped to the upstart Players League to pitch for John Ward’s Brooklyn team in 1890 for $3,200 (approximately $92,000 today), with a $500 advance.35 With Brooklyn, Weyhing was touted as “one of the swiftest pitchers in the business.” On May 30 he endured personal tragedy when his mother died unexpectedly.36 Tracked down by telegraph while traveling with the team, he was unable to get back to Louisville in time for her funeral. Just weeks later, John Weyhing (who had last appeared for an inning in a single game in 1889 for the Columbus Solons) died after a year-long battle with tuberculosis.37 In the aftermath of this difficult time, Weyhing began to make headlines for unruly off-field behavior.

The Ward’s Wonders were in Buffalo to finish the 1890 season and played their penultimate game against the last-place Bisons on October 2. Gus, who had finished his 1890 season 30-16, with a 3.60 ERA and only 17 hit batsmen, observed the game from the grandstand where he “engaged in an animated conversation with Umpire Snyder” that resulted in Weyhing being tossed from the stands.38 He returned after the game in an intoxicated state and was arrested on charges of disorderly conduct after using “vile language” in the presence of ladies.39 These charges, however, were dismissed the next morning and no fine was imposed, much to the disappointment of the Buffalo Courier: “[I]t is a pity that he was not made an example of, for he richly deserved a good-sized fine.”40 More trouble would follow.

A cadre of ballplayers and a “well-known official under the local government” gathered at the Piel Brothers beer hall in Brooklyn following the end of the 1890 season.41 As the group enjoyed an ample quantity of German lager, it was suggested that Weyhing might keep his “arm in practice” by tossing a sandwich at the finely painted ceiling.42 With a rapid succession of sloppy sandwich missiles “hurled with unerring precision,” Weyhing transformed a fresco of Gambrinus “into a huge plot of butter and mustard.”43

In the ensuing week, Weyhing was made the victim of an elaborate practical joke in which he was “arrested” for the damage. A private detective served him with a phony arrest warrant and his lunchmates were provided bogus subpoenas. At a nearby tavern, the witnesses appeared with their subpoenas, along with a representative from the district attorney’s office who “formally” announced the charges against Weyhing. As Gus sat at a table with his head in his hands, he was sentenced to a year imprisonment. Weyhing relented, “I’ll pay whatever damage was done!” The group enjoyed some liquid refreshments at his expense and after he was $10 (nearly $300 today) poorer, Weyhing was finally let in on the joke.44 Unfortunately, a spy in attendance snitched to Gottfried Piel, who had been previously unable to identify the perpetrator. On October 21 a legitimate warrant for Weyhing’s arrest was issued on Piel’s charge of malicious mischief for the damage estimated at $200 (approximately $5,700 today).45 Weyhing had already headed back home to Louisville for the offseason by this time, perhaps unaware of his fugitive status.

The Players League folded after its inaugural season so Weyhing returned to the Philadelphia Athletics for 1891 at a salary of $2,500.46 On the way to Washington for a game on April 23, the train made a scheduled stop in New York at 2:15 a.m.47 As Weyhing slept on the train he was awakened by Brooklyn policemen and hauled off to the Tenth Precinct station house, where he “finished his interrupted nap.”48 Later that morning, friends posted $500 bail and Gus was off to Washington to rejoin the Athletics.49 He took the 4-2 loss on April 24 and there was no further mention of the fresco flap in the newspapers. Despite a rocky 1-5 start in April, Weyhing regained his status as the ace of the Athletics staff. He completed the 1891 campaign 31-20, with a 3.18 ERA in 51 starts, good for a career-high pitching bWAR of 9.9 and an overall bWAR of 7.8 (after factoring in his hitting and fielding). His trademark wildness returned, however, as he hit 31 batters and uncorked 28 wild pitches. The Philadelphia Athletics disbanded following the 1891 season, so Weyhing was again without a club.

On January 26, 1892, the case of “William Joyce” was called in Louisville city court. Joyce was charged with larceny for having stolen a pair of pigeons from a Louisville pigeon show that had closed the night before. The man who approached the bench, however, was immediately recognized as “the athletic form of Gus Weyhing, the celebrated base-ball pitcher.” Weyhing, a pigeon fancier, had entered eight birds for competition at the exhibit. As Weyhing left the exhibition, a pair of missing blondinettes—valued at $50 each (approximately $1,400 today)—were found in his basket and identified by numbered tags. The rightful owner had him arrested, but Gus had identified himself to the police as William Joyce, a former teammate in Brooklyn.50 Apparently suffering no penalty for having offered a false identity, Weyhing’s lawyer had the case continued in order to allow him to have his witnesses present.51 On January 30, the case was dismissed because the complaining witness was not present in court. Regardless, Weyhing’s attorney asked to put on the case anyway to clear Weyhing’s name. Gus and several witnesses took the stand, resulting in a not guilty verdict on the merits.52

In February 1892 Philadelphia Phillies owner Colonel John Rogers inked Weyhing for the season at a salary of $3,250 (approximately $93,500 today).53 Rogers proudly showed off the contract, pointing to the “the name of the erratic twirler written in bold German” at a press conference where he also announced having signed Roger Connor. As a member of the Phillies, Weyhing partially attributed his success to the revenge killing of a snake. Gus and teammate Lave Cross housed pigeons and chickens at Forepaugh Park (home of the Players League Philadelphia Quakers). The day after the Barnum and Bailey circus arrived, several of Weyhing’s birds turned up missing and the main suspect was a large green circus snake that had escaped its enclosure.54 Cross emptied a pistol into the snake and a postmortem examination confirmed their grim suspicions. Weyhing had the snake’s hide turned into shoes that he wore proudly for years to come.

Weyhing turned in a stellar season for the 1892 Phillies, posting a 32-21 record and 2.66 ERA in 49 starts. In relief, he also finished a league-best 10 games, retroactively being credited with a league-best three saves. He again led his team with a pitching bWAR of 9.0 and overall bWAR of 7.4. He added another 18 hit batsmen to his tally. Before the 1893 season, he declared that he would play in Louisville for the NL Colonels or not at all.55 Colonel Rogers was not concerned, “Oh, Gus always gets a funny fit like that this time of the year. You know Weyhing’s home is in Louisville, but he has twirled for the Phillies so long that he would not be content to play in any other city. Yes, we will have Gus all right next year. In fact, we could not do without him.”56

On March 7, 1893, the National League magnates abolished the pitcher’s box, the front of which had been 50 feet from home plate, to “a boundary plate covering a twelve-inch space” at the now familiar 60’ 6” distance.57 Unable to coax his release from the Phillies, Weyhing returned for the 1893 season, taking a pay cut to $1,800 despite his success the prior season. Whether it was the greater pitching distance, the cumulative toll of having averaged 438 innings pitched over the previous six seasons, or issues in his personal life, the 26-year-old Weyhing was not quite as dominant in 1893, posting a 23-16 record as his ERA ballooned to 4.74. Despite the increased pitching distance, Weyhing plunked another 20 men. On September 25 he filed for divorce in Louisville and in October, his cigar manufacturing company went out of business.58

Prior to the 1894 season Weyhing accepted an invitation from University of Pennsylvania baseball coach Arthur Irwin to teach his pitchers the secrets of the “pretzel-curves” for which he was famous.59 For the 1894 Phillies, whom Irwin also managed, Weyhing would post his final winning season at 16-14—in spite of a 5.71 ERA, likely buoyed by a team that hit .350 for the season, including future Hall of Fame outfielders Sam Thompson (.415), Ed Delahanty (.405), and Billy Hamilton (.403). Gus tacked on another 15 HBP, but tossed only five wild pitches, a career low for any of his full seasons. He met again with the University of Pennsylvania pitchers after Philadelphia’s regular season ended, a training session that also drew interest from the team’s prospective catchers.60

Weyhing began the 1895 season again training with the University of Pennsylvania nine. He was confident the Phillies were to be “very strong in the [pitcher’s] box” for the coming season.61 However, he was wild and ineffective in a pair of starts and, on May 4 was given his ten days’ notice of release.62 As soon as his release was final on May 13, he was signed by Connie Mack to pitch for the Pittsburgh Pirates, having spurned offers from St. Louis and Louisville.63 Weyhing made a single start for Pittsburgh on May 21, earning the win and smacking a double against Washington, all while wearing a “white cap of large dimensions” that mismatched his teammates’ blue caps.64 He was injured on May 26 when he was hit in the side during batting practice, perhaps fittingly, by an errant pitch by teammate Tom Colcolough.65 Mack released Weyhing on May 27, claiming the Pirates already had enough pitching.66

After years of preseason threats that he would play in Louisville or nowhere, Weyhing finally inked a deal with his hometown team on June 13, 1895.67 He made his Colonels debut the next day in Philadelphia and was treated rudely by his former team as he yielded 19 hits, walked five, and gave up 17 runs. At least he did not hit a batter. This appearance was significant for another reason: his three consecutive starts for three different ball clubs would not be matched until Jaime Garcia repeated the feat in 2017.68 Weyhing was relatively unproductive for the Colonels, finishing his season 7-19 with a 5.41 ERA, punctuated by a fistfight with umpire Fred Jeyne in a train car en route to Louisville on September 16.69

Prior to the 1896 season, Weyhing issued “his annual message in which he says he will show some people how good ball is pitched.”70 He also made preseason news by shaving his mustache.71 Neither his bravado nor lack of facial hair would help his diminishing effectiveness, however. Weyhing made five starts for Louisville and despite a 2-3 record—including a final home win over Brooklyn on May 13—he was released on May 23.72 It was reported a day earlier that Weyhing had withdrawn a suit for divorce, having again reconciled with Mollie.73

On June 1, Weyhing headed to Rochester, New York, after catching on with the Browns of the Class A Eastern League.74 He was roughed up in his initial start for Rochester on June 9, taking the 14-5 loss against the Springfield Ponies, and was no better in his final start on July 21, giving up 17 hits in a 14-2 loss to the Scranton Miners.75 He was released by Rochester on July 25 after compiling 5-5 record in 10 starts and one scoreless relief appearance.76 Just three years removed from a 20-win season with the Phillies, 29-year-old Weyhing found himself unable to stick in the Eastern League, an association he had ironically disparaged as “simply a minor concern” when compared to the NL shortly after signing with the club.77

Bereft of a major league suitor in 1897, Weyhing agreed to become a player-manager for the Fort Wayne Indians of the Class B Interstate League. Before the season started, however, ownership decided to move in a different direction after confronted with the exorbitant salary demands of the players Weyhing was signing.78 He found himself instead with the 1897 Dallas Steers of the Class C Texas League, playing for manager John McCloskey, a fellow Louisvillian. Weyhing had a rough season for Dallas, compiling a 13-13 record, with an ERA in the neighborhood of 7.00.79 Despite his troubles, Weyhing remained prideful, reporting that he was “doing well in the Texas League.”80

Surprisingly, Weyhing was able to parlay this unspectacular season into a return to the National League with Washington in 1898. Despite a 15-26 record and surrendering a league-high 181 earned runs for the Senators that season, he was the most valuable pitcher for the 11th-place team.81 Weyhing was also able to get himself a mid-season bonus of sorts, when he successfully filed a writ of attachment for $500 in salary owed to him by the Dallas club, earning admiration in his putting one over on a magnate.82 His hit-by-pitch total of 16 did not even make the top-ten for the year. Weyhing pitched similarly for the Senators in 1899, compiling a 17-21. His 28 hit batsmen was third in the League.

On January 26, 1900, Washington owner Earl Wagner travelled to Louisville to sign several of his players who lived in the area. At the time, there were rumors that the National League was planning to “retire” four teams, but Wagner was reportedly proceeding under the assumption that Washington would be part of the league in 1900.83 On March 9, however, Weyhing was sold to the Brooklyn Superbas for $500 in a mass roster liquidation by Wagner after the NL contraction was made public.84 But before the season commenced, Weyhing was cut by Brooklyn manager Ned Hanlon.85

Weyhing reported to have contracted typhoid fever and as of April 1 was still convalescing in Louisville.86 Days later, it was reported that his wife Mollie had deserted him and that he would “no longer be responsible for her debts.”87 (In November he would formally file for divorce from Mollie in Louisville, not knowing her whereabouts.88) On April 18, he was signed by the St. Louis Cardinals, but released after seven appearances.89 Weyhing exacted his revenge on the Cardinals, however, by suing to attach St. Louis’s share of the gate receipts for the game so he could recover $100 the team allegedly owed him for the ten days’ notice of his release.90,91 Hanlon re-signed him on July 28 and Gus was serviceable in his eight starts for Brooklyn, finishing 3-4 with a 4.31 ERA. He made his final start for the Superbas on September 18, losing to former teammate Cy Young. Hanlon released Weyhing on September 20, just weeks before Brooklyn was crowned National League champion.92

Weyhing married Mamie Gehrig (Lou Gehrig’s cousin) on January 9, 1901 at the First English Lutheran Church in Louisville.93 The Weyhings moved into an 1,100-square-foot, shotgun-style home at 1421 Rufer Avenue.94 He began the 1901 campaign with the Western Association Louisville Colonels and pitched himself back to the big leagues by compiling a 14-6 record in 20 starts through July 3. It was initially reported that manager Walt Wilmot released Weyhing so he could join the Cleveland Blues of the nascent American League.95 A conflicting story, however, reported that Weyhing had instead deserted the Louisville club because Wilmot refused a demand to increase his pay from $225 per month to $250, allegedly related to increased living expenses that would be incurred due to the mid-season move of the Louisville club to Grand Rapids, Michigan.96 That he jumped his contract is probably supported by the Western Association having blacklisted him.97

Gus was ineffective in a pair of appearances for the Cleveland Blues and was released July 18.98 On August 14 manager Bid McPhee reported that Cincinnati was “so hard up for pitching talent that he was forced to pick up Weyhing, whom, he understands, is behaving and faster than he has been for several summers.”99 Described as an “antique twirling marvel” who had “been playing hide and seek with the big leagues,” Gus made a single start for the Reds on August 21 against Rube Waddell and the visiting Chicago Orphans. Weyhing took the complete-game 9-1 loss, having given up three earned runs. Chicago right fielder Jock Menefee was hit by pitches twice that afternoon, numbers 276 and 277 of Weyhing’s record-setting career. He was released by Cincinnati on August 25 and never again appeared in the major leagues.100

In 1902 Weyhing compiled a combined 11-14 record and 4.14 ERA for the Memphis Egyptians (Southern Association) and Kansas City Blues (American Association). The following season, he split his time between the Southern Association Little Rock Travelers and Atlanta Crackers; (incomplete) 1903 statistics revealed similar results—an 11-13 record and 5.10 ERA.101 Weyhing did not play professional baseball in 1904 but was appointed an American Association umpire on July 26.102 A lawsuit filed in 1904 by John Sauer & Co. claimed Weyhing owed $237.63 for leaf tobacco purchased in 1903 for his Louisville cigar store.103

Weyhing returned to baseball in 1910 as the first manager of the Tulsa Producers in their inaugural season in the Western Association.104 He was credited there with innovating the display of NL, AL, and Western Association game scores in the ballpark “as quickly as [they] can be bulletined.”105 His tenure was short-lived, however, as the club was already on its third skipper before the end of May.106 Perhaps surprisingly, the 43-year-old Weyhing resurfaced as a player on May 6 with the Texas League Galveston Sand Crabs, starting the second game of a doubleheader against the Oklahoma City Indians. He pitched well but was tagged with the loss in the 2-1 ballgame.107 In his final professional appearance on May 25, 1910, Weyhing was pulled after giving up two runs in three innings against the Waco Navigators.108 Galveston won the game, but the reliever was credited with the win. Weyhing was released on May 27 and immediately applied to become a Texas League umpire.109

Weyhing made his umpiring debut on June 28.110 The very next day, he was called out by the Houston Buffaloes for using profane language following an argument over a protested call.111 His temperament likely led to his demise as an umpire; just weeks into his umpiring foray, Horace Shelton of the of the El Paso Herald urged the Texas League president “to keep a pink slip handy” after Waco fans found fault with Weyhing’s safe call on a steal of home on July 12.112 This appears to have been the final game Gus worked behind the plate.

Weyhing and Emmett Rogers tried unsuccessfully to organize a Class D Southern Oklahoma league in 1911, with Gus set to manage the Shawnee franchise.113 A league with the same name was established in 1916, but by this time, Weyhing was a patrolman for the Louisville Police Department.114 He worked thereafter as a saloonkeeper and night watchman at the Louisville Water Company.115 He lived out the remainder of his life quietly with Mamie in Louisville. They had no children. Although Weyhing was credited with the nickname “Cannonball,” the author has not found any contemporaneous accounts of that moniker used during Weyhing’s playing days. The first appearance of “Cannonball Gus” was found in a 1942 article.116

Gus Weyhing died at home on September 4, 1955, of arteriosclerosis and was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Louisville. He was survived by his wife Mamie, who was buried next to Gus in 1966.

Besides remaining the undisputed leader in hit batsmen with 277, Weyhing holds some other dubious distinctions. In 2016, James Shields of the White Sox became the first hurler since Weyhing in 1895 “to allow seven-plus runs over the first three innings of a game, six times in one season.”117 Weyhing is also still seventh on the all-time list for errors by a pitcher (128), likely due to his status as the last major league pitcher to play without a glove.118

Overall, Weyhing ranks 40th all-time with 264 wins, 18th with 232 losses, 12th with 449 complete games and 22nd with 19,188 batters faced. He is also fifth all-time with 240 wild pitches, tenth with 1,570 bases on balls, and seventh with 1,872 earned runs. Six times he finished in the top ten for strikeouts per nine innings.

On what would have been Weyhing’s 107th birthday, the Chicago Tribune recalled that Weyhing had worked as a saloonkeeper—just like his father—in Cincinnati. When business soured, “the sheriff notified Gus that he’d have to vacate the place by July 1. Weyhing put a sign in the window: ‘The first of July will be the last of August.’ You have to like a guy like that.”119

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank SABR member Frank Vaccaro for his assistance with citations for several details of Weyhing’s life.

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Dennis Pajot.

Sources

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.familysearch.com

Notes

1 “The Three Big Teams,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 20, 1890: 17.

2 US Census Bureau, 1870 US Census. (Note: Weyhing’s mother is listed also as “Catherine” and “Katerina.”)

3 1870 US Census.

4 US Census Bureau, 1880 US Census.

5 1880 US Census

6 U.S. Patent No. 755,133, issued March 22, 1904.

7 “The Ball Game,” Richmond (Indiana) Item, September 26, 1885: 1.

8 “Base Ball,” Cambridge City (Indiana) Tribune, October 1, 1885: 3.

9 “Base Ball,”

10 “Base Ball,”.

11 August Weyhing clipping file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library; David L. Porter, Frank J. Olmstead, Biographical Dictionary of American Sports (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000).

12 “Baseball Prospects,” Richmond Item, January 19, 1886: 1.

13 “Base Ball,” (Nashville) Tennessean, January 25, 1886: 8.

14 “Baseball,” (Memphis, Tennessee) Public Ledger, April 26, 1886: 2.

15 “Only Two Games,” Atlanta Constitution, May 16, 1886, 12. (Ramsey pitched for the AA Louisville Colonels in 1886.)

16 “Ball Notes in the South,” Philadelphia Times, July 4, 1886: 11.

17 “The Diamond,” Public Ledger, July 15, 1886: 3.

18 “Sporting,” Buffalo Enquirer, August 25, 1898: 8.

19 “Gus Weyhing to Go East,” Louisville Courier-Journal, March 12, 1887: 3.

20 “A Game of Errors,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 9, 1887: 7.

21 “The Ball Games,” Philadelphia Times, April 10, 1887: 6.

22 “Diamond Dust,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 25, 1887: 3.

23 “The Association,” Philadelphia Times, May 6, 1887: 1.

24 “The American Association,” Indianapolis Journal, May 6, 1887: 3.

25 Louisville Courier-Journal, July 17, 1887: 7.

26 The rookie HBP record was broken in 1896 by Danny Friend of the Chicago Cubs, with a still-standing record of 39 HBP.

27 “Base Ball,” Philadelphia Times, March 25, 1888: 16.

28 Date is approximate. “America’s Games,” York (Pennsylvania) Dispatch, July 7, 1888: 1. (John Weyhing pitched for the 1888 Cincinnati Red Stockings and in eight starts went 3-4 with a 1.23 ERA.)

29 “American Association,” Chicago Inter Ocean, July 7, 1888: 2.

30 “American Association”.

31 “Brooklyn Bewildered,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 29, 1888: 16.

32 “The Athletics Scalp the Cow-Boys,” Philadelphia Times, August 1, 1888: 4.

33 This was the major league record for a season until 1891 when Columbus Salons hurler Phil Knell plunked a staggering 54 batters, still the major league season record.

34 New York Clipper, September 30, 1893: 496.

35 “Base Ball Notes,” Boston Globe, December 31, 1889: 5.

36 Kentucky Deaths and Burials, 1843-1970.

37 August Weyhing clipping file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, “Another Death in the Weyhing Family,” June 28, 1890.

38 “Buffalo Wins a Hard-Fought Battle,” Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express, October 3, 1890: 6; Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, October 3, 1890: 6.

39 “Weyhing’s Bad Break,” Sporting Life, October 4, 1890:1

40 “Diamond Glints,” Buffalo Courier, October 5, 1890: 7.

41 “Weyhing the Ball Tosser,” Brooklyn Times Union, October 21, 1890: 1.

42 “Weyhing the Ball Tosser”

43 “Want Weyhing,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 21, 1890: 6; “Weyhing the Ball Tosser,” Brooklyn Times Union, October 21, 1890: 1.

44 “Gus Weyhing Was Arrested,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 24, 1890: 2.

45 “Weyhing the Ball Tosser,” Brooklyn Times Union, October 21, 1890: 1. The Piel Brother’s brewery and beer hall was located five blocks from Eastern Park, home of the Brooklyn Ward’s Wonders and was a favorite haunt for “Capt. Johnny Wards’ ball players.” Part of the original building still stands on the northeast corner of Sheffield and Liberty; “Want Weyhing,” Brooklyn Eagle, October 21, 1890: 6.

46 “With the Athletics’” Louisville Courier Journal, February 11, 1891: 2.

47 “Caught on the Fly,” Brooklyn Citizen, April 23, 1891: 1.

48 “Gus Weyhing Arrested,” Philadephia Inquirer, April 24, 1891: 2; “He Got in a Box,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 23, 1891: 6.

49 “Caught on the Fly,” Brooklyn Citizen, April 23, 1891: 1.

50 “Weyhing Accused of Laceny,” Chicago Inter-Ocean, January 27, 1892: 6.

51 “Found in Weyhing’s Basket,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, January 27, 1892: 9.

52 “Weyhing Honorably Discharged,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, January 31, 1892: 11.

53 “Roger Connor and Gus Weyhing Fall into Line,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 12, 1892: 3.

54 “Weyhing’s Slippers,” Buffalo Courier, April 24, 1898: 21. In the article Weyhing misremembered that he played for the Phillies in 1891.

55 “Connor Will Stay Here,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 1, 1893: 3.

56 “Connor Will Stay Here,”

57 “Men of the Diamond,” Chicago Tribune, March 8, 1893: 7.

58 “Sixty Witnesses,” Louisville Courier-Journal, October 14, 1893: 7; New York Clipper, September 30, 1893: 496. It appears the couple reconciled, and no divorce decrees was issued at that time.

59 “Vail’s Men Win,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 7, 1894: 3.

60 “Plenty of Base Ball Material,” The Philadelphia Times, October 16, 1894: 8.

61 “Gossip from the Field of Sports,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 20, 1895: 4.

62 “Gus Weyhing to Go,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 5, 1895: 19.

63 “The Pennant Race,” Pittsburg Press, May 14, 1895: 5.

64 “An Awful Massacre,” Pittsburg Post, May 22, 1895: 6.

65 “Weyhing Has a Rib Broken,” Philadelphia Times, May 27, 1895: 8.

66 “Gus Weyhing Released,” Pittsburg Press, May 27, 1895: 1.

67 “Sporting Notes,” Pittsburg Post, June 14, 1895: 6.

68 “Yankees Go Down Quietly,” Hartford Courant, August 5, 2017: C4.

69 “Baseball Notes,” Brooklyn Times Union, September 17, 1895: 6.

70 “Baseball Notes,” (Lincoln) Nebraska State Journal, January 26, 1896: 19.

71 “About Ballplayers,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 3, 1896: 15.

72 “Louisville Goes to Pieces,” Chicago Tribune, May 24, 1896: 6.

73 “Diamond Dust,” Bureau County Tribune (Princeton, Illinois), May 22, 1896: 2.

74 “Base-Ball Gossip,” Louisville Courier-Journal, June 2, 1896: 6.

75 “Scranton Passes Wilkes-Barre,” (Scranton, Pennsylvania) Times-Tribune, July 22, 1896: 3.

76 “Base Ball,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) News, July 31, 1896: 3.

77 “Baseball Notes,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Sunday Leader, July 19, 1896: 3.

78 “It’s Manager Meyer,” Fort Wayne (Indiana) News, February 10, 1897: 1.

79 Baseball-Reference.com does not list any statistics for Weyhing’s 1897 campaign with Dallas. These numbers are approximations based on the author’s thorough review of box scores, line scores, and articles found in the Austin American-Statesman for the 1897 season and are probably incomplete.

80 Wilkes-Barre Sunday News, July 4, 1897: 5.

81 Baseball-Reference.com lists Weyhing’s pitching WAR as 3.2 and overall WAR 2.5, both tops on the team for pitchers.

82 Washington (DC) Evening Star, July 5, 1898: 9.

83 “Earl Wagner in the City,” Louisville Courier-Journal, February 27, 1900: 8. In retrospect, it is likely that Wagner needed signed contracts in hand for the 1900 season in order to sell his players to the remaining National League teams, and he had simply feigned ignorance regarding the immediate future of his Washington club.

84 “League Good to Freedman,” Brooklyn Citizen, March 10, 1900: 5. Baseball Reference transaction entry showing a March 9, 1900 purchase of Weyhing by Brooklyn from St. Louis is incorrect. Weyhing’s contract was purchased from the folding Washington franchise.

85 “Baseball Gossip,” Buffalo Enquirer, March 28, 1900: 4.

86 “Among the Ballplayers,” The Lexington (Kentucky) Herald, April 2, 1900: 8.

87 “Ball Player’s Wife Deserts,” Topeka (Kansas) State Journal (Topeka, Kansas), April 3, 1900: 2. Research of genealogy, census, and marriage records has not revealed any further information about this Mollie Weyhing’s maiden name.

88 “Base Ball Notes,” Washington Evening Star, November 6, 1900: 9.

89 “Sporting Notes,” Pittsburg Post-Gazette, April 19, 1900: 6.

90 “Row at Brooklyn,” Buffalo Review, September 20, 1900: 2.

91 “Base Ball Notes,” Washington Evening Star, July 28, 1900: 9.

92 “Notes of the Game,” Brooklyn Citizen, September 21, 1900: 6.

93 Kentucky, County Marriage Register, 1901: 64-65; August Weyhing clipping file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, David L. Porter, Frank J. Olmstead, Biographical Dictionary of American Sports (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000); Death notice, January 18, 1964.

94 https://www.zillow.com/homedetails/1421-Rufer-Ave-Louisville-KY-40204/131835700_zpid/, accessed September 4, 2019.

95 “Notes,” Dayton (Ohio) Herald, July 3, 1901: 6.

96 “Gus Weyhing Comes Home,” Louisville Courier-Journal, July 4, 1901: 7.

97 “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, July 23, 1901: 2.

98 “His Second Discontent,” (Knoxville, Tennessee) Journal and Tribune, July 19, 1901: 3.

99 “Chat of the Game,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, August 14, 1901: 3.

100 “Only Four Hits,” Boston Globe, August 26, 1901: 2.

101 These numbers are approximations based on the author’s review of box scores, line scores, and articles for that season and are probably incomplete.

102 “Too Hot for Bug Holliday,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 28, 1904: 6.

103 “Pitcher Weyhing Sued,” Louisville Courier-Journal, November 3, 1904: 10.

104 “Weyhing at Tulsa,” Wichita (Kansas) Beacon, March 12, 1910: 7. Baseball Reference lists the Tulsa team name as the “Oilers.” It appears that the official name was the “Producers,” selected following a naming contest that drew 3000 suggestions. “‘Producers’ is the Name,” Coffeyville (Kansas) Journal, April 5, 1910: 3.

105 “Hook Slide Required,” (Guthrie) Oklahoma State Capital, April 10, 1910: 8.

106 “Missouri Town Going Strong in Western Association Race,” Fort Worth Record and Register, May 22, 1910: 13.

107 “They Broke Even,” Shreveport (Louisiana) Times, May 7, 1910: 7.

108 “Sand Crabs Won Game,” Shreveport Times, May 26, 1910: 7.

109 “Weyhing Would be Umpire,” Houston Post, May 28, 1910: 4; Baseball Reference lists Weyhing as manager of the 1910 Guthrie Senators of the Western Association; however, the author was unable to find any reports to corroborate.

110 “Diamond Dots,” Oklahoma City Pointer, June 29, 1910: 3.

111 “Base Running Wins Contest from Houston,” Oklahoma City Pointer, June 30, 1910: 3.

112 Horace H. Shelton, “Texas League Notes,” El Paso Herald, July 15, 1910: 8; “Miserable Afternoon for Waco,” Shreveport Times, July 13, 1910: 6.

113 “Magnates Busy Signing Men,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, January 22, 1911: 44.

114 “Southern Oklahoma League is Organized,” (Oklahoma City) Oklahoman, March 13, 1916: 6; “Hans Wagner Sees His Old Pal, Gus Weyhing,” Dayton (Ohio) News, April 9, 1916: 22.

115 “Big League Star of 1890s, ‘Gus’ Weyhing, Dies Here,” Louisville Courier-Journal, September 5, 1955: 1.

116 Bill Gottlieb, “Who was Dodgers’ Leading Pitcher?” Brooklyn Eagle, June 14, 1942, 29; Weyhing was referred to as “Doggie” in “Comedians of Baseball,” Washington Post, September 4, 1910, 31.

117 Coleen Kane, “Tough Omen for Sox,” Chicago Tribune, August 25, 2016: 5.

118 Charles F. Faber, Baseball Prodigies: The Best Major League Seasons by Players Under 21, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2014), 227.

119 “Cursory Anniversary,” Chicago Tribune, September 29, 1973: 159.

Full Name

August Weyhing

Born

September 29, 1866 at Louisville, KY (USA)

Died

September 4, 1955 at Louisville, KY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.