April 26, 1902: Addie Joss dodges a Toledo sheriff, then stifles the Browns for a one-hit shutout in his debut

On the third Sunday of April 1902, Toledo sheriff Charley Pierce waited at the Neil House, a landmark hotel in downtown Columbus, Ohio,1 for a guest who never arrived. Pierce was there, at the hotel where the American League’s Cleveland Blues would be spending the night,2 to execute a warrant for the arrest of Adrian “Addie” Joss, who’d been indicted several days earlier. Learning that the sheriff was waiting to arrest Joss, Blues officials spirited the 22-year-old pitcher off the team’s train before it pulled into Columbus.3

On the third Sunday of April 1902, Toledo sheriff Charley Pierce waited at the Neil House, a landmark hotel in downtown Columbus, Ohio,1 for a guest who never arrived. Pierce was there, at the hotel where the American League’s Cleveland Blues would be spending the night,2 to execute a warrant for the arrest of Adrian “Addie” Joss, who’d been indicted several days earlier. Learning that the sheriff was waiting to arrest Joss, Blues officials spirited the 22-year-old pitcher off the team’s train before it pulled into Columbus.3

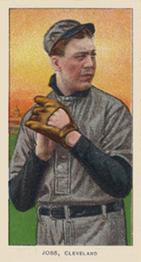

Joss, a 6-foot-3 right-handed phenom, had spent the previous season dominating opponents for Charles Strobel’s Toledo Mud Hens of the Western Association, winning 27 games and fanning 210.4 That summer, while bidding wars raged between the first-year American League and the established National League, the AL’s Boston Americans and NL’s St. Louis Cardinals each offered Strobel $1,500 for Joss’s contract. Former major leaguer Arlie Latham, acting for an anonymous bidder, asked Strobel to name his price.5 Joss being the Mud Hens’ primary gate attraction, Strobel declined to part with him at any price.

Unbeknownst to Strobel, Charlie Ebbets met with Joss in August to recruit him for the National League and his Brooklyn Superbas. In September, the St. Louis Republic reported that Ebbets had “iron-clad contracts” with the six of the Western Association’s strongest players, including Joss.6 A month later, Bill Armour, manager of the Cleveland franchise, claimed Joss was joining his squad in the American League;7 an agreement reportedly sealed with a $500 bill.8

In December the Detroit Free Press claimed Joss had “come to an ‘understanding” and would pitch for Toledo;9 yet weeks later he appeared on preseason rosters for both Brooklyn and Cleveland.10 Strobel vowed to fight to hold onto Joss.11 “If Joss … attempts to play in Brooklyn this coming season I will begin action against both [him] and the Brooklyn Club.”12

It became clear in late March that Joss, described as a “jumper” in the press,13 was heading not to Brooklyn, but to New Orleans for spring practice with Cleveland.14 Strobel vacillated for a time,15 then filed charges. He claimed Joss had accepted a $150 contract advance on false pretenses, later returning $100 and pocketing the rest. A grand jury in Toledo sided with Strobel, and on April 16 issued an indictment and a warrant for Joss’s arrest.16

Two days after he’d skirted Sheriff Pierce, Joss traveled to Toledo and turned himself in. He paid a $500 bond to avoid jail until a trial could be held, and joined his teammates in St. Louis for the start of the 1902 season.17

Cleveland opened the regular season with a four-game series against the St. Louis Browns at newly refurbished Sportsman’s Park. Though they bore the name of the team that had dominated the American Association in the 1880s before becoming a National League cellar-dweller in the 1890s, these Browns were a reborn American League franchise. Relocated from Milwaukee, where they’d been known as the Brewers, this was their first year in St. Louis.

Debuting new solid blue road uniforms, the Blues fell to the Browns on Opening Day—and the next. (Unhappy with the playful nickname “Bluebirds” that those uniforms engendered with the public, the Cleveland ballplayers would soon start calling themselves the Bronchos; a name modern databases mistakenly ascribe to the 1902 season in toto.)18 In the third game of the series, Clarence “Gene” Wright, another Western Association pitcher whom Armour lured away from Ebbets, dominated the Browns, throwing a two-hit shutout. Emboldened by Wright’s performance, Joss, scheduled to face St. Louis the next day, proclaimed, “If Wright could hold them down to two hits I will hold ’em down to four.”19

The Saturday, April 26, series finale pitted Joss against St. Louis native Wee Willie Sudhoff, in his first start after jumping from the NL Cardinals.20 Umpiring the game was Bob Caruthers, ace of three Browns American Association championship teams and the one-time interim manager of the NL Browns, in his first year as an American League arbiter.21 As was common for that time, Caruthers (whose name was often misspelled as “Carruthers” in box scores) was the only umpire working the series.

The game got underway on a comfortable afternoon, shortly after a zephyr passed through the city, tearing off roofs, signs, and at least one chimney.22 Both teams went scoreless in the first inning, with Joss fanning fellow Wisconsin native Davy Jones for his first career strikeout.23 In the second inning, Joss struck out the side on 10 pitches. “The mighty Jesse] Burkett looked like a has been and the popular Bobby] Wallace an exploded myth,” a St. Louis sportswriter opined.24

Sudhoff matched Joss inning for inning, holding Cleveland hitless through the third inning.25 Jack McCarthy led off the fourth with a single for the Blues’ first hit, and reached third on a one-out single to center by Osee Schrecongost. After Schreck (as the Cleveland first baseman was typically called) was gunned down trying to steal second, Sudhoff escaped without allowing a run.

In the top of the sixth, the Blues threatened to break the deadlock. Ollie Pickering singled to center with one out, stole second, and reached third on another McCarthy single. Zaza Harvey, who’d collected six hits the day before, scorched a grounder to third baseman Barry McCormick. As McCormick threw to first, the speedy Pickering broke for home. 26 First baseman John Anderson fired a strike to catcher Jiggs Donohue, who tagged out a sliding Pickering.

The “entire Cleveland nine” argued that he was safe, with captain Frank Bonner’s “forceful and unpleasant” protests earning him a seat in the bleachers.27 When Caruthers threatened to eject a few more ballplayers, Cleveland stopped kicking.28

Controversy marked the bottom of the sixth as well. With one out, Burkett hit a low line drive to right field. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported that Harvey “came in on the dead run and scooped the ball up just as it struck the ground. Whether he got it before it actually touched the latter or not it was impossible to say.”29 Caruthers ruled that the ball hadn’t been caught, giving the Browns their first hit. Harvey protested, to no avail.30

After play resumed, Burkett advanced to second on an out and to third on a passed ball. Joss walked Jones, who then stole second. With “heavy hitter” Anderson batting,31 Burkett broke for home on a one-strike pitch. Anderson, either unaware of the steal attempt or fearing that Burkett might be thrown out, “lost his head” and swung, hitting a liner to left field. McCarthy snared the ball a foot off the ground and threw to third base in time to double up Burkett, ending the inning.

Cleveland finally scored in the seventh. A grounder from Schreck rolled through the legs of shortstop Wallace, and with two outs John Gochnaur drew a walk. After going hitless in his first 14 major-league at-bats, rookie Harry Bemis singled to left field, plating Schreck with the first run of the game.

Joss followed with a drive that either hit or went over the left-field bleacher fence and bounced back onto the field for his first major-league hit. The Blues claimed it was a home run but Caruthers awarded Joss a double, and allowed both baserunners to score. The Blues were now leading 3-0.

The ball had hit the “top molding,” according to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.32 The Cleveland Plain Dealer claimed a “high wire screen” denied Joss a home run in one game summary, and in another story asserted he was entitled to a home run because the ball hit a post in the right field bleachers.33 The St. Louis Republic noted that Joss’s drive was the first to strike the new Grand Avenue bleachers on the fly.

Back in Cleveland, Joss’ bold pregame prediction had drummed up immense interest in the game. Crowds gathered around scoreboards and ticker-tape machines set up by the Cleveland Plain Dealer to follow Joss’s debut, with readers shouting out the results of each play.34 When the ticker began reporting results of the seventh inning, riveted fans fell silent. The tape reader’s cry of “nothing for St. Louis” brought a sigh of relief. “Bedlam reigned supreme” after a call of “three for the Bluebirds,”35 with “hats, umbrellas and canes waving in the air.”36

Joss held the Browns scoreless and hitless over the final two innings to secure a one-hit shutout. “Three lusty cheers from hundreds of throats rent the air” as the final score appeared on Cleveland scoreboards.37 The next day, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch marveled at how Joss “appeared to make the St. Louisians quail.”38 He was “invincible from start to finish,” according to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.39

After his debut, attention turned to Joss’s pending trial. Cleveland owner Charles Somers made clear that the club would fight to keep him.40 That commitment included giving Strobel the rights to Cleveland pitcher Jack Lundbom in compensation for losing Joss.41

On July 5, Joss traveled back to Toledo to appear before the grand jury. His attorney submitted a motion to quash the indictment, which the prosecuting attorney elected not to contest. The case against Joss was dismissed.42

Joss went on to compile a 17-13 record in his rookie season, with a league-leading five shutouts, and a top-10 finish in strikeouts (106), WHIP (1.114), and ERA (2.77). An impressive start to a brief but brilliant Hall of Fame career.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Ray Danner and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Statscrew.com for pertinent information, including the box score and play-by-play. He also relied on summaries of this game published in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and St. Louis Republic newspapers and Scott Longert’s biography Addie Joss: King of the Pitchers (Cleveland: SABR, 1998); and Alex Semchuck’s SABR biography of Addie Joss, Charles F. Faber’s SABR biography of Bob Caruthers, and Bill Nowlin’s SABR biography of Osee Schrecongost.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/SLA/SLA190204260.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1902/B04260SLA1902.htm

Notes

1 The Neil House was the former residence of recently assassinated President William McKinley while he served as Ohio governor (1892-1896).

2 The Blues were completing a series of exhibition games as they worked their way back to Cleveland from spring training in New Orleans.

3 “Addie Joss,” Columbus Dispatch, April 21, 1902: 11.

4 Joss’s Toledo statistics are taken from Scott Longert, Addie Joss: King of the Pitchers (Cleveland: SABR, 1998), 31.

5 Longert.

6 “New Timber for Brooklyn,” St. Louis Republic, September 25, 1901: 7.

7 In addition to Joss, Armour claimed three other players would be joining Cleveland who’d recently been signed by Brooklyn. They were pitcher Clarence “Gene” Wright, and infielders John Gochnaur and Ed Wheeler, all former members of the Western Association’s Dayton (Ohio) Veterans. Wright and Gochnaur ultimately played for Cleveland in 1902, while Wheeler stayed with Brooklyn. “Harmony Reigns in the National,” Pittsburg Press, October 27, 1901: 25.

8 Longert, 37.

9 “About the Ball Tossers,” Detroit Free Press, December 10, 1901: 9.

10 “Two League Teams,” Sporting Life, February 15, 1902: 3; “Dayton Doings,” Sporting Life, January 11, 1902: 10.

11 “Baseball Suit Still in Court,” Pittsburg Press, January 5, 1902: 18; “Strobel Will Fight for Players,” St. Louis Republic, January 7, 1902: 6.

12 Strobel’s position was that Toledo was “under the protection of the National League,” via the National Agreement, which bound all teams in professional leagues to obtain the release of a reserved player, such as Joss, before signing them. “Savage Strobel,” Sporting Life, January 18, 1902: 10.

13 See for example, “Brief Sporting Items,” New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, March 22, 1902: 3, and E.B. Johns, “Toledo Topics,” Sporting Life, March 29, 1902: 8.

14 “Cleveland Chatter,” Sporting Life, March 29, 1902: 3.

15 Sporting Life reported that in early April, Strobel had elected to “take no legal steps” to force Joss to abide by the contract he claimed Joss has signed the previous December. “News and Gossip,” Sporting Life, April 12, 1902: 5.

16 The warrant specified that Joss was to be arrested upon his return to Ohio. “‘Addie’ Joss in Trouble,” Portage (Wisconsin) Register, April 17, 1902: 4.

17 “Addie Joss Surrenders,” Omaha World-Herald, April 23, 1902: 2.

18 Cleveland featured solid blue road uniforms from 1902 through 1904, prompting fans and the press to start calling the team Bluebirds shortly before the 1902 season began. The Bronchos name began appearing in the press by the end of May 1902. “Will Be Two Local Leagues,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 16, 1902: 12; “Lajoie and Bernhard Report in Cleveland,” Columbus Dispatch, May 28, 1902: 13.

“Dressed to the Nines: A History of the Baseball Uniform,” Hall of Fame website, http://exhibits.baseballhalloffame.org/dressed_to_the_nines/uniforms.asp?league=AL&city=Cleveland&lowYear=&highYear=&sort=year&increment=9, accessed August 8, 2022.

19 “Thoughts for Fandom,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 26, 1902: 6.

20 Sudhoff , who’d won 17 games the year before for the Cardinals, was the first Missouri-born ballplayer to play for both the Browns and the Cardinals. Brian Flaspohler’s Willie Sudhoff SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Willie-Sudhoff/.

21 Most recently an umpire in the Western League, Caruthers was hired by AL President Ban Johnson prior to the 1902 season. “Tabeau Talks of Brashear,” St. Joseph (Missouri) News, January 28, 1902: 6.

22 The high temperature for the day was 63 degrees. “What the Wind Did,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 27, 1902; National Weather Service past weather website, https://www.weather.gov/wrh/climate, accessed August 5, 2022.

23 Joss was born in Woodland, Wisconsin, northwest of Milwaukee, and first achieved baseball notoriety while playing for teams in Juneau, Wisconsin. Jones, two months younger than Joss, was born in Cambria, Wisconsin, 40 miles northwest of Woodland.

24 “Joss To [sic] Much for New Browns,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 27, 1902: 18.

25 In his 1998 biography of Addie Joss, author Scott Longert describes Joss being baited by veterans Burkett and a Jack O’Connor in the top of the third inning. He recounts a dialogue the pair had (between the first-base and third-base coaching boxes) in which they mocked Joss’s minor-league credentials and his curly locks. Their heckling had the hometown crowd roaring with laughter, according to Longert. Joss gave them no satisfaction, so the pair blocked his path to the Cleveland bench after the fourth inning, forcing him to walk around them. There’s no mention of this banter (or of Joss being blocked by the pair) in any of the game summaries published in St. Louis or Cleveland newspapers. Additionally, O’Connor wasn’t a Brown until the 1904 season. (He played for the Pittsburgh Pirates throughout the 1902 season.) This suggests that the story may be apocryphal. Longert, 44.

26 Pickering was the Blues’ top basestealer in 1901, with 36. No other Blues player had more than 15.

27 According to the St. Louis Republic, Bonner was the first AL player ejected during the 1902 regular season. The short-fused Caruthers led the league’s umpires with 22 ejections during the 1902 season. Bonner was ejected again by Caruthers 10 days later for arguing a call at first base. “Two Coats of Whitewash,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 27, 1902: 22.

28 When the kicking was done, Jack Thoney replaced Bonner at second base, making his major-league debut. “Joss Holds Browns to a Solitary Hit.”

29 “Browns Were Blanked,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 27, 1902: 12.

30 Author Scott Longert claimed that Caruthers made the call from behind home plate, and so was in a poor position to see what happened. A remark in the St. Louis Republic that Caruthers “umpired all the games from back of the pitcher’s box” implies that he may have actually had the best view possible in a single-umpire game. Longert, 44; “Joss Holds Browns to a Solitary Hit.”

31 Anderson led the 1901 Milwaukee Brewers with eight home runs.

32 “Browns Were Blanked.”

33 The St. Louis Post-Dispatch agreed with the wire-screen version, adding that the ball struck the wire 15 feet over (left fielder) Burkett’s head.[33] “Two Coats of Whitewash”; Edwards, “Brown’s [sic] Get One Hit Off Joss”; “Joss To [sic] Much for New Browns.”

34 Longert, 45.

35 Bluebirds was a name applied to the Cleveland squad that first appeared in the press prior to the 1902 season. By late May the team would be known as the Bronchos, a name selected by the Cleveland ballplayers, who were unhappy with the not-so-manly Bluebirds moniker. Modern databases, such as Baseball-Reference.com, identify the 1902 Cleveland team as the Bronchos. “Will Be Two Local Leagues,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 16, 1902: 12; “Lajoie and Bernhard Report in Cleveland,” Columbus Dispatch, May 28, 1902: 13.

36 Edwards, “Brown’s [sic] Get One Hit Off Joss.”

37 “Brown’s [sic] Get One Hit Off Joss.”

38 “Joss To [sic] Much for New Browns.”

39 “Browns Were Blanked.”

40 “Joss’ Joke,” Sporting Life, May 3, 1902: 13.

41 It’s unclear exactly when Lundbom, a right-handed spot starter for the Bronchos, was released to Toledo. He last pitched for Cleveland on June 21, and first appeared in a Toledo box score after a game on July 12. Lundbom was released by Toledo in August and returned to Cleveland, pitching in three more games for them that season. “Baseball Gossip,” Buffalo Enquirer, August 18, 1902: 4; “To-day’s Games,” Cleveland Leader, July 13, 1902: 22.

42 Author Scott Longert claimed that the grand jury itself elected to quash the indictment after Joss’s attorney submitted the motion. “The Case of Joss,” Sporting Life, July 12, 1902: 6; “General News of Sport,” Elkhart (Indiana) Truth, July 12, 1902: 3; Longert, 46.

Additional Stats

Cleveland Blues 3

St. Louis Browns 0

Sportsman’s Park

St. Louis, MO

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.