August 13, 1953: Campanella, Furillo home runs lead Dodgers to comeback win

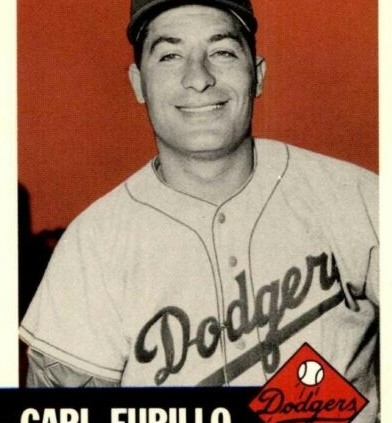

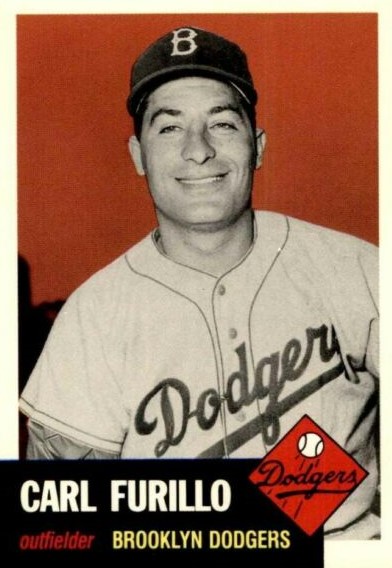

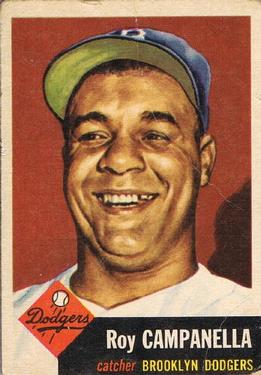

Roy Campanella — “The husky backstop is recognized as one of the greatest fielding catchers of all time. Carl Furillo — “It was his great throwing arm that earned him the nickname of ‘The Reading Rifle.’” — Topps Baseball Archives1

The 1953 season was a banner one for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Late in the season, Jackie Robinson put it this way, “We have the ball club this year, the kind of team it takes to beat the Yankees. We have the power, the kind of hitters who can belt the ball out of the park at any time, at any pitch.”2 Indeed, the lineup was stacked with .300 hitters: Gil Hodges (.302), Roy Campanella (.312), Jackie Robinson (.329), Duke Snider (.336), and Carl Furillo (.344). They led the major leagues with 208 home runs and the National League in many offensive categories, including batting average (.285). And Carl Erskine threw his first 20-win season for good measure.

The 1953 season was a banner one for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Late in the season, Jackie Robinson put it this way, “We have the ball club this year, the kind of team it takes to beat the Yankees. We have the power, the kind of hitters who can belt the ball out of the park at any time, at any pitch.”2 Indeed, the lineup was stacked with .300 hitters: Gil Hodges (.302), Roy Campanella (.312), Jackie Robinson (.329), Duke Snider (.336), and Carl Furillo (.344). They led the major leagues with 208 home runs and the National League in many offensive categories, including batting average (.285). And Carl Erskine threw his first 20-win season for good measure.

In first place since late June, they pulled away to win the National League crown by 13 games over the Milwaukee Braves. The Dodgers won consecutive National League pennants, the first time for the franchise since 1899-1900.

Two Dodgers took away highly esteemed individual honors. Furillo won the NL batting crown and Campanella was named the league’s Most Valuable Player for a second time.3 A game in August against their archrivals, the New York Giants, illustrates what they contributed to the Dodgers’ success in 1953.

The Dodgers were finishing a grueling 16-game road trip with three games at the Polo Grounds. Having won the first two games against the Giants, they were playing a third game only because of early-in-the-season April showers.

Before returning to New York, they swept a three-game series in Cincinnati, so they were now sporting a five-game winning streak. Billy Loes (12-6, 4.57 ERA), the Dodgers’ starting pitcher, gained one of those wins over the Reds with 3 2/3 innings of one-hit relief pitching. The Giants started rookie Al Worthington (2-4, 2.47 ERA). Worthington’s major-league debut in July couldn’t have gone any better. He shut out the Phillies 6-0 at the Polo Grounds on two hits on July 6 and then proceeded to shut out the Dodgers 6-0 on four hits at Ebbets Field five days later.

Over the first three innings, Worthington picked up where he left off in his previous start against the Dodgers, limiting them to a walk by Hodges. Meanwhile, Loes yielded a two-run homer to deep left field by Wes Westrum in the second inning after Daryl Spencer walked. When Al Dark hit a solo home run to deep left in the third, the Giants led 3-0.

With two outs in the fourth inning, the Dodgers were ready to break through against Worthington after Robinson walked and Campanella singled him to second. Hodges’ double to left-center scored Robinson, but Campanella was thrown out at the plate, Bobby Thomson to Spencer to Westrum.

The Dodgers tried to stay in the game with single runs in the fifth and sixth innings. In the fifth, George Shuba singled to right with one out. Manager Charlie Dressen decided to have Wayne Belardi pinch-hit for Loes. When Belardi singled to left and Jim Gilliam doubled to right, Shuba scored. Dave Anderson of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle agreed with Dressen’s decision and didn’t mince words: “Loes was useless again, his third straight knockout as a starter.”4 In the sixth, Robinson singled and Campanella walked, setting up Furillo’s first-pitch RBI single to center off Worthington for the Dodgers’ third run.

Dodgers’ relief pitchers Bob Milliken and Jim Hughes were largely ineffective as the Gants widened their lead. In the fifth inning, Westrum walked and misfortune struck Milliken. Worthington reached safely on a sacrifice bunt and Hodges’ fielding error. Dark’s RBI foul fly down the right-field line and three successive singles resulted in three runs, all unearned. In the sixth, with Hughes on the mound, Spencer opened with a bunt single down the third-base line. With two outs, the Giants again packaged three successive singles for two more runs and an 8-3 lead. Erv Palica came in to get the last out, Hank Thompson’s fly ball to center.

Those runs ended the Giants’ offense for the evening. Over the last 4⅓ innings, Palica, Ben Wade, and Clem Labine limited the Giants to two singles, allowing the Dodgers’ bats to make it a game again.

Those runs ended the Giants’ offense for the evening. Over the last 4⅓ innings, Palica, Ben Wade, and Clem Labine limited the Giants to two singles, allowing the Dodgers’ bats to make it a game again.

The seventh inning started with Worthington walking Gilliam and yielding singles to Bobby Morgan and Snider for a Dodgers run. Worthington was replaced by knuckleballer Hoyt Wilhelm.5 Giants manager Leo Durocher didn’t even get to make that change since he had been banished in the fifth inning after arguing balls and strikes with umpire Bill Jackowski.6 Wilhelm retired Robinson on a fly ball, but Campanella arced a 295-foot home run into the lower right-field stands for his 30th of the season, scoring Morgan and Snider ahead of him and cutting the Giants’ lead to a single run, 8-7.

The Giants carried that one-run lead into the ninth. When Campanella returned to bat in the ninth inning, he hit Wilhelm’s first pitch, probably a knuckleball, the other way right down the left-field line. Joseph Sheehan of the New York Times noted that it was “a pop fly that Al Dark confidently expected would descend into his glove.”7 However, the ball nicked the protruding left-field scoreboard at the Polo Grounds for Campanella’s 31st home run and a tie game.

Labine’s second consecutive three-up-three-down inning sent the game to the 10th inning. On Wilhelm’s very first pitch of the inning, Furillo lofted his 17th homer into the left-field stands. Labine closed out the Giants in their half of the 10th inning for the 9-8 Dodgers win.

For the Dodgers, the victory was their sixth straight on their way to a season-long streak of 13 wins in a row.8 Dodgers fans could celebrate a sweep of the Giants. Sheehan was quick to point out the symmetry of this game with the one the night before — Giants squander a five-run lead, Labine is the winning pitcher and Wilhelm is the losing pitcher.9 The bats of both Campanella and Furillo were hot at the very same time. Campanella had now hit safely in eight consecutive games, 13 hits, 4 home runs, and 12 runs batted in, on his way to a season-long streak of 12 games. Furillo was matching the Dodgers’ winning streak with a six-game hitting streak of his own with 12 hits to raise his average to .331.

Furillo continued his torrid hitting with four hits in his next game against the Pirates, opening the Dodgers homestand. He raised his average to .344 before disaster struck on September 6. Giants pitcher Ruben Gomez hit Furillo on the wrist during a typically heated Dodgers vs. Giants game at the Polo Grounds.10 Furillo charged the Giants’ dugout and was met by Giants manager Leo Durocher, a continuation of a feud that had been simmering for years. In the ensuing melee, Furillo broke a bone in his left hand, ending his season. He won the batting title when Red Schoendienst’s last-weekend-of-the-season attempt to pass him fell two points short (.342).11

Meanwhile, Campanella continued his march toward several batting records. By season’s end his 41 home runs and 142 runs batted in set several new marks.12 His home-run total set a new Dodgers mark previously held by Gil Hodges’ 40 homers in 1951. His RBI total easily broke the old mark of 130 held by Babe Herman (1930) and Jack Fournier (1925). Measured against other catchers, Campanella’s 142 runs batted in broke the previous National League record of 122 set by Walker Cooper (1947) and Gabby Hartnett (1930) as well as the major-league mark of 133 set by Bill Dickey (1937).

While this story emphasizes the offensive prowess of Roy Campanella and Carl Furillo in the 1953 season, their baseball cards highlight their considerable defensive skills.13 Campy and Skoonj made the 1953 Brooklyn Dodgers one of the best!14

Author’s note

Baseball cards like the ones illustrated in this essay tell the story of ballplayers in pictures, numbers, and words. The rich history of baseball cards and collectors has been told in SABR’s Baseball Research Journal.15 For the young Brooklyn Dodgers fan of the 1950s, the name of the game was baseball-card flipping and tossing with friends to augment the collection, primarily putting doubles at risk to do so.16

Simply put, flipping requires a second player to try to match the picture facing up (heads) or the statistics facing up (tails) of the card flipped by the first player. On the other hand, tossing requires a “playing field” such as the front steps of a house. Get your card closer to the bricks of the stoop than any of your opponents and you won, perhaps even with a leaner. The playing field in this case was often shared with a game of stoopball played with a spaldeen ball manufactured by Spalding.17 Great fun!

Sources

The author accessed Baseball-Reference.com for box scores/play-by-play information (baseball-reference.com/boxes/NY1/NY1195308130.shtml) and other data, as well as Retrosheet.org (retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1953/B08130NY11953.htm).

Notes

1 Baseball cards #27 (Roy Campanella) and #305 (Carl Furillo) are from the Topps’ Ultimate 1953 Series.

2 Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson (New York: Ballantine Books, 1997), 259.

3 Roy Campanella won the NL MVP award in 1951, batting .325 with 33 home runs and 108 runs batted in. He won a third league MVP award in 1955, batting .318 with 32 home runs and 107 runs batted in.

4 Dave Anderson, “Brooks in Spot to Put Clamp on Flag Chase,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 14, 1953: 11.

5 The 30-year-old Wilhelm was in only his second major-league season of a 21-year Hall of Fame career.

6 When Leo Durocher retired from major-league baseball in 1973, his 95 career ejections as a manager were surpassed only by John McGraw (132). The record is now held by Bobby Cox (161).

7 Joseph M. Sheehan, “Brooklyn’s Rally Brings 9-8 Victory,” New York Times, August 14, 1953: 11.

8 “Brooks 13-Game Skein Compiled Against 3 Clubs,” The Sporting News, September 2, 1953: 7.

9 Sheehan.

10 Louis Effrat, “Furillo and Durocher Stage Battle; Dodger Player Fractures Left Hand,” New York Times, September 7, 1953: 1.

11 Carl Furillo picked up where he left off. In the 1953 World Series against the Yankees, he batted .333 (8-for-24) with two doubles, one home run, four runs batted in, and four runs scored.

12 Anderson.

13 Given an opportunity that came only once, would Hall of Fame catcher Roy Campanella have been able to handle Hall of Fame pitcher Hoyt Wilhelm’s knuckleball? SABR author Mark Armour wrote, “His fabulous knuckleball began to attract attention for how difficult it was to catch. After selecting Wilhelm to the 1953 All-Star team, National League manager Charlie Dressen expressed concern over whether Roy Campanella would be able to catch him, and Hoyt did not pitch.” Too bad! (Mark Armour, “Hoyt Wilhelm,” SABR Baseball Biography Project).

14 Furillo’s nickname “Skoonj” was the shortened form of the Italian word scungilli, meaning snail, which was his favorite dish.

15 Arthur Zillante, “Review: Books on Baseball Cards,” Baseball Research Journal, Summer 2010.

16 “Baseball Card Games,” Streetplay.com, streetplay.com/thegames/baseballcards.shtml.

17 Paul Dickson, The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, 3rd Edition (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009). Page 830, Stoopball: “A variation of baseball played without a bat, usually one to a side. A rubber ball is thrown against a set of steps (or stoop) by the player on offense, while the defense tries to catch the ball on the fly as it comes off the stoop.” Page 807, Spaldeen: “The smooth, hollow, pink, high-bouncing rubber ball used in such baseball variations as stickball, stoopball, punchball, and box baseball.”

Additional Stats

Brooklyn Dodgers 9

New York Giants 8

10 innings

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.