August 5, 1893: Washington’s Cub Stricker arrested while Phillies shellac Senators

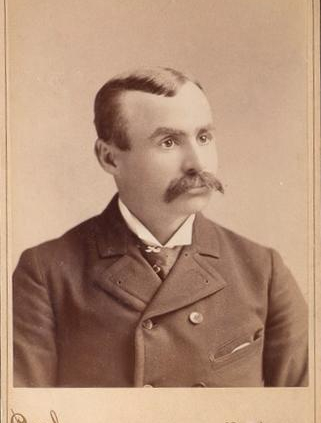

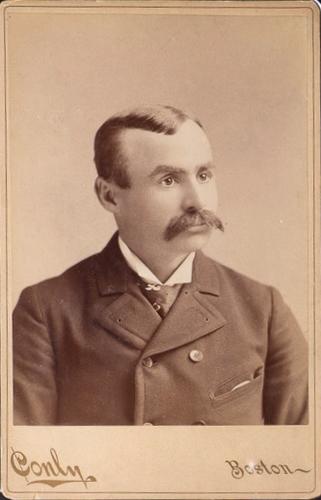

Philadelphia native John “Cub” Stricker began his baseball career amid the amateur ranks as a teenager in 1878. Five years later he was the starting second baseman of his hometown Athletics. And on October 1, 1883, the 5-foot-3, 138-pound Stricker paraded around a euphoric Philadelphia with his teammates; the Athletics were champions of the American Association. The Philadelphia Item noted Stricker’s demeanor, writing, “The happiest man in the line was Stricker. He was one continuous smile.”1 Even the antique gray mule that pulled Stricker’s milk wagon – his offseason occupation – was in the parade.2 It was the best of times.

Philadelphia native John “Cub” Stricker began his baseball career amid the amateur ranks as a teenager in 1878. Five years later he was the starting second baseman of his hometown Athletics. And on October 1, 1883, the 5-foot-3, 138-pound Stricker paraded around a euphoric Philadelphia with his teammates; the Athletics were champions of the American Association. The Philadelphia Item noted Stricker’s demeanor, writing, “The happiest man in the line was Stricker. He was one continuous smile.”1 Even the antique gray mule that pulled Stricker’s milk wagon – his offseason occupation – was in the parade.2 It was the best of times.

Ten years later, it was the worst of times.

On August 2, 1893, the Washington Senators3 arrived in Philadelphia mired in 11th place in the 12-team National League, a half-game ahead of the tailender Louisville Colonels. The Philadelphia Phillies were in second place, only four games behind the league-leading Boston Beaneaters. The three-game series was originally scheduled to be played in Washington but was moved to Philadelphia for financial reasons.4

The Phillies scored 7.60 runs per game in 1893, second only to Boston’s 7.69. Their 1,011 runs scored led the league. The Senators surrendered the most runs in the league, allowing 7.94 runs against per game and 1,032 total runs for the season. Consistent with those track records, the Phillies won 22-7 in the opener, on August 3, and 14-7 a day later. On Saturday, August 5, the 12th and final meeting between the teams for the 1893 season was witnessed by a large crowd of 10,440.5

Washington manager Jim O’Rourke could not field his standard lineup for the series finale, with four players playing out of position. First baseman Henry Larkin got drunk the previous night, missed curfew, and arrived late to the ballpark on Saturday. He was fined and suspended.6 Sam Wise, the third baseman, suffered from cholera, so backup catcher Deacon McGuire was moved to first base, O’Rourke shifted from the outfield to catcher, Duke Farrell went from catcher to third base, Stricker played second base, and pitcher Al Maul played left field.

The Phillies batted first and opened the contest with a bang when leadoff hitter Lave Cross smashed an Otis Stockdale curve to center field for a double. Bill Hallman and Sam Thompson followed with successive singles to right field, scoring Cross. A force at second on Ed Delahanty’s grounder left runners at the corners with one out. Jack Boyle doubled to right-center, plating Hallman. Jack Clements continued the barrage with a single to right, bringing home both Delahanty and Boyle and increasing the Phillies’ advantage to 4-0.

The Phillies piled on five more runs in the second before the Senators got on the scoreboard in the bottom of the inning. With one out, Weyhing walked Maul. Joe Sullivan bunted for a single and Weyhing hit Paul Radford to load the bases. Stricker bunted for a hit, scoring Maul. Sullivan and Radford scored on Stockdale’s single to center. Two more Washington runs followed, narrowing the Phillies’ lead to four runs.

Philadelphia’s offense continued to churn with two more runs in the third to make it an 11-5 game. The Inquirer’s baseball correspondent described the atmosphere: “The slugging done by the Phillies tickled the crowd and they hurrahed and shouted to their heart’s content for three innings. … [T]hen the Senators changed pitchers.”7 Maul replaced Stockdale in the box for the fourth and sent the Phillies down in order. In the Senators’ half, Stricker bunted for a hit, advanced on Stockdale’s sacrifice, and scored when Hallman made a wild throw, cutting the deficit to 11-6.

After trading runs in the fifth, the Phillies exploded for seven runs in the sixth inning, to the crowd’s delight. “[The Phillies] hit the ball on the nose again,” the Inquirer explained, “and the Senators played as though their hands were full of grease. … [T]he excitement rose to fever heat.”8

Sharrot popped a ball into short right field. Amid shouts from the crowd in the right field bleachers to muff the ball, Stricker ended the inning by making a fine catch. Stricker said something to the fans, who responded in kind. Then things got interesting.

“‘Cub’ drew back his right arm and threw the ball in the direction of the right-field seats.”9 The ball bounded over the short fence and hit fan William Wright in the face, breaking his nose. Police officers assisted Wright to the pavilion where he was examined by a doctor.10

The ballpark was pandemonium for the next five minutes as fans shouted for Stricker’s ejection and arrest. Umpire Jack McQuaid and police Sergeant Charles Egolf approached Stricker but took no action. The incensed crowd “hooted vigorously” at Stricker, the Inquirer recounted, yelling, “We’ll fix you after the game!”11

Fan riots on the field in Philadelphia had happened before.12 Sergeant Egolf feared another one was brewing. Before the Senators batted in the ninth, Egolf arrested Stricker and took him to the 22nd District Station, near the ballpark. “Here he had a consultation with Wright … and the latter was induced to withdraw the charge.”13 Stricker sneaked out the back of the station house, avoiding the angry fans who congregated at the front.

The Phillies tacked on two more runs in the seventh, and they led 21-7 as the Senators went to bat in the bottom of the ninth. “Maul tripled with one out. Delahanty made a running catch on a deep fly by Sullivan. Maul tagged and Delahanty launched the ball to Clements at the plate. “It was a close race between Senator Maul and the ball,” the Inquirer reported, “but the Senator won by about two inches.”14

The crowd thought that Delahanty’s throw was in time, which would have ended the game. They jumped onto the field and made for the exits. The Inquirer described the scene. “It was a shouting, howling mob, and there were only four policemen to control it.”15 Washington’s O’Rourke tried to convince McQuaid to forfeit the game to the Senators, claiming the game could not resume. Phillies manager Harry Wright implored the crowd to return to their seats, telling them, “Gentlemen, if you don’t get back we will lose the game.” The masses complied and the game resumed.

Weyhing walked Radford and suddenly the Senators were in a dilemma: It was Stricker’s turn in the order, but he couldn’t come to the plate because he was at the police station. Both the Inquirer and Sporting Life claimed Washington didn’t have a substitute. But why? Rule 25, Section 1 of the rule book stated that teams were required to have at least one substitute available.

Washington’s roster was composed of 13 players on August 5. With Larkin suspended and Wise sick, only 11 players were available to play. Pitcher Jouett Meekin was used as a late-game defensive replacement in left field. The only active Washington player not to appear in the game was Duke Esper, who had pitched the previous day and may not have even been at the ballpark, leaving Meekin as the only available substitute.

If another Senator batted, Stricker would be declared out because he would have been skipped in the batting order, thus ending the game. Radford took matters into his own hands by attempting to steal second base and was put out by pitcher Frank O’Connor for the game’s final out. The Phillies defeated the Senators, 21-8. But the day’s action was not over.

A 20-minute cushion battle commenced as patrons began to leave the ballpark by way of the playing field. Fans in the pavilion began to throw cushions at those leaving. “The thickest of the fight was on the right field side of the pavilion,” said the Inquirer.16 Those on the field began to throw the cushions back “and then stormed the stand.” The excitement escalated to the pavilion’s upper deck. Cushions were strewn about the field. “The battle was so fierce and the struggle so great that the heavy railing in front of the pavilion was pulled out of place, and at one time, when forty men and boys were clinging to it, it looked as if it would fall.”17 The festivities ended when the combatants became exhausted.

Thanks to Sporting Life, we know who prevailed: “The field crowd had less ammunition, but more numbers, and the pavilion fighters were finally routed.”18

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org for pertinent information.

Notes

1 “Reception Notes,” Philadelphia Sunday Item, October 7, 1883: 6.

2 “The Base Ball Parade,” Philadelphia Times, October 2, 1883: 1.

3 This club was part of the American Association in 1891 and the National League from 1892 through 1899. It is not related to the American League’s Washington Senators/Nationals of the twentieth century.

4 John B. Roche, “From Washington,” Sporting Life, August 5, 1893: 1.

5 The NL’s average attendance in 1893 was 2,778.

6 John B. Roche, “Washington Whispers,” Sporting Life, August 12, 1893: 2.

7 “A Base Ball Row and Cushion Fight,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 6, 1893: 1.

8 “A Base Ball Row and Cushion Fight.”

9 “A Base Ball Row and Cushion Fight.”

10 “Stricker’s Escapade,” Sporting Life, August 12, 1893: 1.

11 “A Base Ball Row and Cushion Fight.”

12 Matt Albertson, “August 26, 1889: Extra baseball, a free fight, and a protest in Philadelphia,” SABR Games Project, accessed May 14, 2023.

13 “Stricker Arrested,” Sporting Life, August 12, 1893: 1.

14 “A Base Ball Row and Cushion Fight.”

15 “A Base Ball Row and Cushion Fight.”

16 “The Cushion Battle,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 6, 1893: 1.

17 “The Cushion Battle.”

18 “After Consequences,” Sporting Life, August 12, 1893: 1.

Additional Stats

Philadelphia Phillies 21

Washington Senators 8

Philadelphia Ball Park

Philadelphia, PA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.