August 7, 1942: First Negro League baseball game is broadcast on radio

While we take radio for granted today, when it came onto the scene in 1920, it was considered a marvel. It was the first mass medium that brought entertainment and information into people’s homes in real time. Most baseball fans were delighted. There were a few games on the air as early as 1921 (including the World Series), and many more American League and National League games were broadcast the following year, making it easier to follow the pennant race. But in segregated America, fans of Negro Leagues baseball were not as fortunate. They would have to wait until August 7, 1942, before a game was finally broadcast. In that game, the Washington Homestead Grays defeated their archrivals, the Baltimore Elite Giants, 7-3.

While we take radio for granted today, when it came onto the scene in 1920, it was considered a marvel. It was the first mass medium that brought entertainment and information into people’s homes in real time. Most baseball fans were delighted. There were a few games on the air as early as 1921 (including the World Series), and many more American League and National League games were broadcast the following year, making it easier to follow the pennant race. But in segregated America, fans of Negro Leagues baseball were not as fortunate. They would have to wait until August 7, 1942, before a game was finally broadcast. In that game, the Washington Homestead Grays defeated their archrivals, the Baltimore Elite Giants, 7-3.

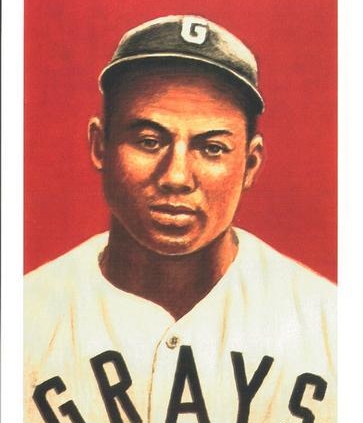

Throughout much of 1942, the Grays and the Giants were locked in a heated battle for first place in the Negro National League. Both teams had built loyal followings, and when they played each other, the games were well-attended.1 The Grays were starting their dominance of the Negro National League; 1942 was their first of four straight World Series appearances. Led by player-manager Vic Harris, they were getting good pitching from lefty Leroy Partlow, and good hitting from right fielder David Whatley and slugging catcher Josh Gibson.

The Giants, led by player-manager Felton Snow, had some good pitchers too, especially Jonas Gaines, the team’s “brilliant southpaw ace.”2 They had clutch hitters as well, including second baseman Sammy Hughes, and an up-and-coming young catcher named Roy Campanella, who was rumored to be getting a major-league tryout in early August.3 In fact, just about every team had players who were drawing cards; in some cities, Negro League contests attracted more fans than the games of the all-white AL and NL teams. This was especially true whenever pitching legend Satchel Paige came to town.4

But unless you were at the games, or subscribed to a newspaper that covered Black baseball, getting information was difficult. The radio stations of that time were not much help; a few stations broadcast the scores of Negro Leagues games, but many others didn’t even do that.5 At each ballpark, there was a public-address announcer who did play-by-play and kept the fans informed about the teams and the players.

At Griffith Stadium, the announcing was done by a well-known Black sportswriter named Sam Lacy; he was sometimes assisted by Harold Jackson, whom Lacy had mentored and trained.6 Jackson dreamed of being a sportscaster, but in 1942, that was not possible. In fact, at that time, there was only one Black sportscaster, New York’s Jocko Maxwell; and while he had a sports show several times a week (and was sometimes a stadium announcer for the Newark Eagles), even he couldn’t find a play-by-play job on any radio station.

There is little surviving information about how the first Negro Leagues radio broadcast came to fruition. What we do know is that the Baltimore Afro-American was the sponsor, and the newspaper’s management collaborated with the D.C.-based Henry J. Kaufman Advertising Agency; the Afro-American, which was celebrating 50 years of publishing that year, agreed to sponsor the entire three-game series, as well as other Homestead Grays games for the remainder of the season.7

We also know that the radio station that broadcast the games was WWDC, one of the newer stations in the area: it had gone on the air on May 3, 1941.8 The station’s chief announcer, soon to become the sports director, used the air name Ray Carson. (At his previous station, he was known as Ray Morgan.) Carson was White, and it was he who did the play-play-play for WWDC during that first game. But he soon had a Black sidekick to assist him with subsequent games: Harold Jackson.9

That first Negro League broadcast took place at Bugle Field in East Baltimore; the park had been built circa 1930 by then-local businessman Joe Cambria, who owned the Bugle Coat and Apron Supply Company. (He owned several semipro and minor-league teams and went on to become a major-league scout for the Washington Senators.10) According to ads in the Afro-American, tickets had been 65 cents at the beginning of the season, but the price was raised in mid-May; from then on, general admission was 85 cents.11

Some attendance estimates said Bugle Field could seat 6,000 fans;12 but we do not have an official attendance for the Friday night game. However, given the rivalry between the Grays and the Giants, and given how well both teams were doing in the standings, the Afro-American’s sportswriters were predicting a capacity crowd.13 And the weather cooperated: after a warm day, the temperature that evening was in the 60s, making it a comfortable night to see a ballgame.

Both teams were aware that a lot was on the line. As Afro-American sports editor Art Carter pointed out, “[T]he 1942 league championship may be decided in [this] series.”14 Even the mainstream (White-run) newspapers, which often ignored the Negro Leagues, paid this series some attention: the Baltimore Sun noted that “the teams are locked in a bitter struggle for first place,” and referred to this series as “the top feud” of Negro Leagues baseball.15 But the anticipation turned out to be greater than the realization for Giants fans; in that Friday night game, they found they had little to cheer about.

Jonas Gaines, who had usually pitched well against the Grays, and had shut them out on only three hits several weeks before,16 had one of his rougher outings of the season. The Grays got to him right away, scoring four runs on four hits in the first inning—including a 379-foot homer by Josh Gibson.17 (In fairness to Gaines, the fielding behind him could have been better; third baseman George Scales, usually known for being a reliable fielder, mishandled a groundball for an error.)

Gaines settled down after that shaky first inning, but in the sixth inning, he gave up two more runs, partly the result of another error—this one by second baseman Felton Snow, which put a man on base. The Grays scored one more in the eighth—a total of seven runs on eight hits. Gaines did strike out 11 batters, but the one person he couldn’t do anything with all night was Gibson, who hit two home runs and drove in four during the game; Gaines also walked him intentionally twice.

As for the Giants, they could not come up with timely hitting. Grays southpaw Roy Welmaker, known for good control and a very effective fastball,18 was not as sharp as he had been in some other games. But he was good enough to win, despite giving up nine hits and three runs. The Giants scored one run in the sixth, driven in by outfielder Wild Bill Wright. And the Giants looked as if they were mounting a comeback in the ninth, when George Scales led off with a home run. But after Felton Snow and Bob Clarke singled, and pinch-hitter Jesse Brown singled in one run, that was all the Giants could come up with, and the rally died out. The final score was 7-3 and it knocked the Giants out of first place.19

It would be interesting to know how the fans reacted to finally being able to listen to a Negro Leagues game on radio, but that too seems lost to history. Members of the Afro-American staff were proud of the accomplishment, however. Baseball writer Ric Roberts praised the newspaper’s pioneering effort and expressed the hope that more Black sporting events would soon be heard on the air.20

Although rain interfered with the Sunday game, several days later, on August 13, the Homestead Grays played the Kansas City Monarchs at Griffith Stadium, and once again the game was on the air. This time, Harold Jackson was able to do some of the play-by-play. (Jackson became a sportswriter for the Afro-American’s Washington office,21 and later, as Hal Jackson, was a popular radio deejay.) And the Grays won that game 3-2, as Roy Welmaker outdueled Satchel Paige.22

Sources and Acknowledgments

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com, and Seamheads.com.

The author would like to thank Baltimore-based librarian Donna Hesson for her assistance. The author is also grateful to John Fredland for his helpful suggestions, Kevin Larkin for fact-checking, and Len Levin for copy-editing.

Notes

1 Bob Luke, The Baltimore Elite Giants: Sport and Society in the Age of Negro League Baseball (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 8.

2 “Pitching Bolstered by Gaines, “ Baltimore Afro-American, June 6, 1942: 25.

3 “Negro Trio Gets Tryout Aug. 4,” Oakland (California) Tribune, July 27, 1942: 10.

4 Ric Roberts, “Grays Outdraw All Sports Events at Griff Stadium; Battle Newark Sunday,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 27, 1942: 26.

5 “Sportscaster Denies Discrimination on Air,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 22, 1943: 26.

6 Hal Jackson, with James Haskins, The House That Jack Built (New York: Amistad Press, 2001), 24-25.

7 “Grays-Elite Series to Be Broadcast,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 8, 1942: 25.

8 “WWDC, Washington Takes Air May 3,” Broadcasting, May 5, 1941: 49.

9 Emory O. Jackson, “Tagging ’Em Out,” Arkansas State Press (Little Rock), August 7, 1942: 7.

10 “Joe Cambria Dies, Once Operated Hagerstown Club,” Hagerstown (Maryland) Daily Mail, September 25, 1962: 12.

11 For example, advertisement in the Baltimore Afro-American, June 13, 1942: 26.

12 Wayne Hardin, “Stadium Sites Recall Glory Days of Black Baseball,” Baltimore Sun, July 24, 1994: M15.

13 Art Carter, “Elites and Grays Open Crucial 3-Game Series,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 8, 1942: 25.

14 Art Carter, “League Title at Stake,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 8, 1942: 25.

15 “Grays Listed,” Baltimore Sun, August 8, 1942: 10.

16 “Grays Nips Monarchs in 11th, Face Elites Sunday,” Baltimore Afro-American, July 25, 1942: 26.

17 Art Carter, “Grays Defeat Elites, 7-3, to Regain NNL Lead,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 11, 1942: 23.

18 “Dave Whatley Shows the Way for Grays in D.C. Games,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 22, 1942: 20.

19 Art Carter, “Grays Defeat Elites, 7-3, to Regain NNL Lead.”

20 Ric Roberts, “All Up in Washington,” Baltimore Afro-American, August 8, 1942: 26.

21 Hal Jackson, with James Haskins, 24.

22 “20,000 See Grays Beat Paige 3-2,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, August 14, 1942: 24.

Additional Stats

Washington Homestead Grays 7

Baltimore Elite Giants 3

Bugle Field

Baltimore, MD

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.