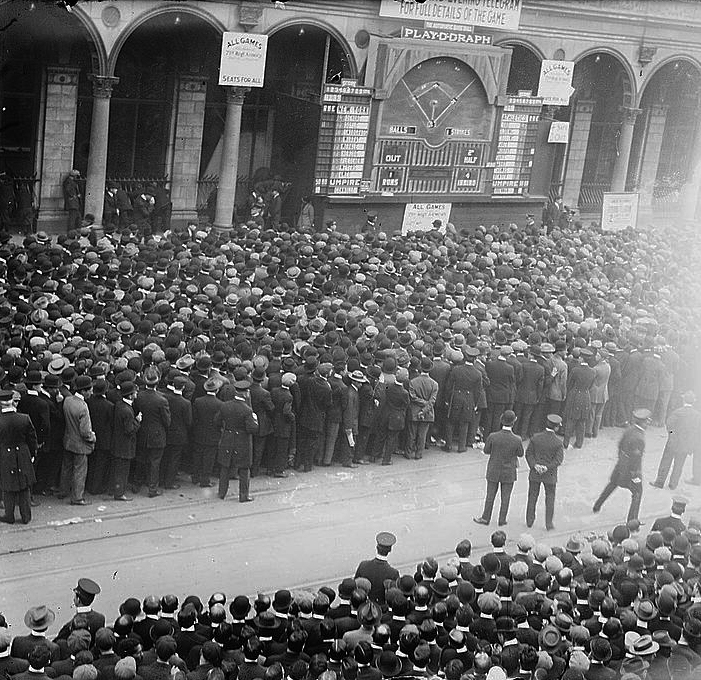

In 1921 many cities did not have a radio station of their own yet, but AM radio signals traveled a long distance and as a result, American listeners in the west could pick up eastern stations like KDKA in Pittsburgh or WBZ in Massachusetts and get the baseball scores.

People in 1921 still didn’t know what to call this new mass medium that had started to bring them news of the games. A few called it “radio,” but many (especially in the newspapers) called it the “radiophone” or the “wireless telephone.”

People in 1921 still didn’t know what to call this new mass medium that had started to bring them news of the games. A few called it “radio,” but many (especially in the newspapers) called it the “radiophone” or the “wireless telephone.”

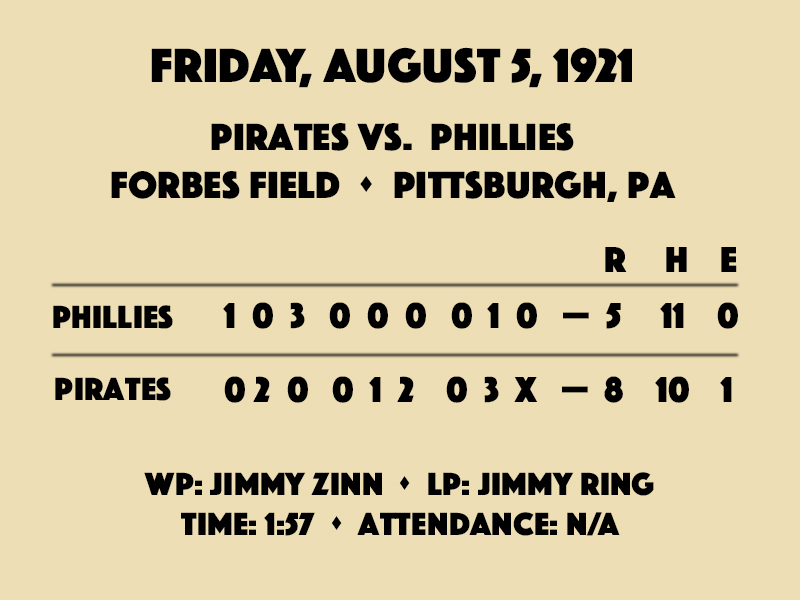

Some baseball game scores and details of play had been transmitted on radio before 1921, among radio enthusiasts. From around 1912 onward, there was a growing number of amateur wireless operators. Some of these experimented with sending out information on baseball scores by voice to friends who were amateur wireless operators themselves. This early amateur experimentation culminated in August 5, 1921, in the first broadcast of a baseball game on commercial radio.

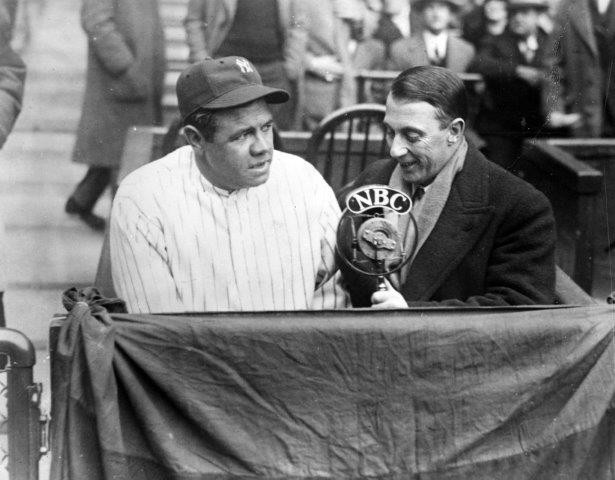

The Pirates were leading the National League when the Philadelphia Phillies rolled into town for this game broadcast by Pittsburgh station KDKA. For the first time, not only was a baseball game transmitted via commercial radio, but Harold W. Arlin also attempted to describe the play-by-play, setting a boundary-challenging example of baseball broadcasting that has continued into the modern era of Internet streaming.

Baseball continues to set new standards in broadcasting today, including the first all-women broadcast team of a game in 2021 between the Baltimore Orioles and Tampa Rays.

— Donna L. Halper and Sharon Hamilton

- Read more: “KDKA’s Harold Arlin broadcasts first baseball game over commercial radio as Pirates rally to beat Phillies,” by John Fredland

- Get the book: Download your free e-book edition of SABR’s Calling the Game: Baseball Broadcasting from 1920 to the Present, by Stuart Shea

Photo: George Westinghouse Museum Collection, Detre Library & Archives Division, Senator John Heinz History Center, Pittsburgh, PA