October 3, 1942: Cardinals stun Yankees on Ernie White’s shutout

After the St. Louis Cardinals beat the New York Yankees 4-3 in St. Louis to even the World Series at one game apiece, the teams traveled to New York for Game Three. Wartime exigencies forced both teams to travel on the same train. It was an awkward arrangement, but there was no intermingling between the players during the 23-hour trip.1

After the St. Louis Cardinals beat the New York Yankees 4-3 in St. Louis to even the World Series at one game apiece, the teams traveled to New York for Game Three. Wartime exigencies forced both teams to travel on the same train. It was an awkward arrangement, but there was no intermingling between the players during the 23-hour trip.1

St. Louis faced a major challenge playing the next three games at Yankee Stadium: New York had won 15 of its last 17 World Series home games. Among the Cardinals, however, there was a sense of excitement about playing in “The House That Ruth Built.” As Marty Marion said, “It was a thrill to play at Yankee Stadium. Let me tell you something about playing in Yankee Stadium. Of all the places to play in baseball, that’s it.”2

While the Cardinals may have been excited, buoyed by their second-game win, the Yankees could not get over the feeling that they had been robbed of victory. They were still grousing about umpire George Magerkurth’s calling Whitey Kurowski’s fly ball down the left-field line fair, a call that gave him a triple and St. Louis a crucial run. That the team wouldn’t let the play go was reflected in manager Joe McCarthy’s berating umpire Bill Summers for the call while the train sped east. Summers had been home-plate umpire for that game.3

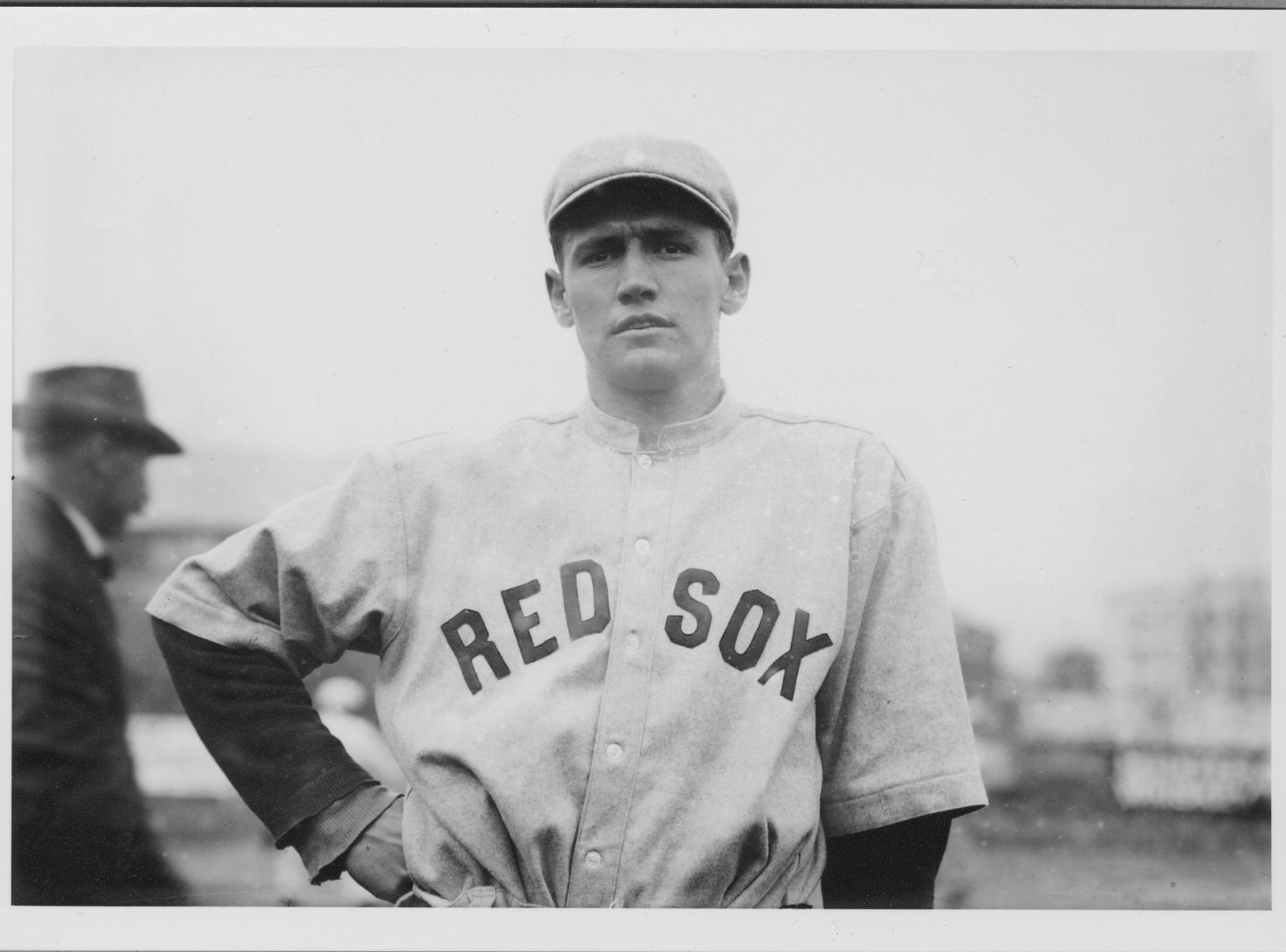

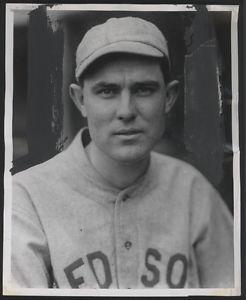

If looking back was not enough, the Yankees openly expressed concerns about facing Cardinals starting pitcher Ernie White. White did not appear nearly as impressive a pitcher as 20-game winners Johnny Beazley and Mort Cooper (who had started for St. Louis in Games One and Two), his seemingly mediocre 7-5 record paling alongside those of his fellow starters. White had won 17 games the previous season, but in 1942 he began the year with a sore arm. Just as he was working himself into shape, he suffered a setback when he was hit by a line drive and putout of play for several weeks.4 Once he recovered, his 3-0 record in September proved crucial to the Cardinals’ stretch drive toward the pennant.

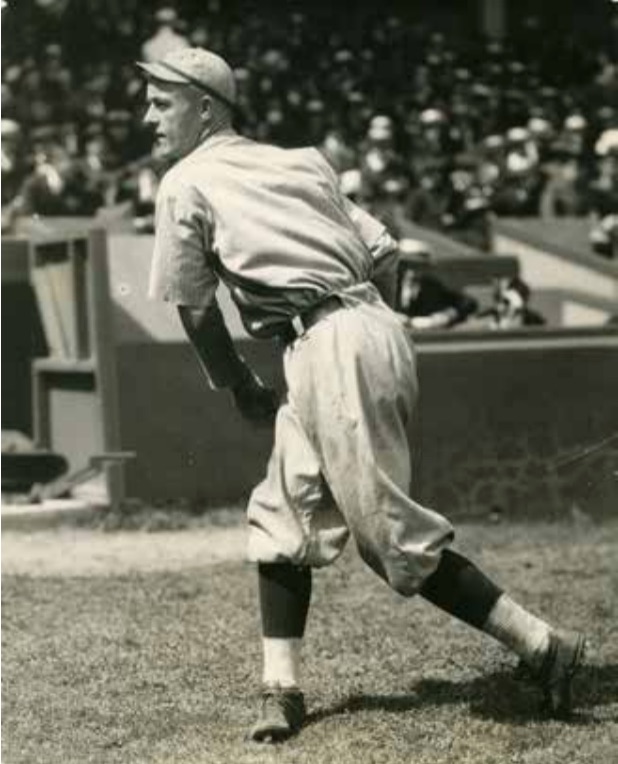

Normally what a player accomplished during the season would make little impression on a World Series opponent. But White had given New York fits during spring exhibition contests. He was the hurler who the Yankees thought “would give (us) the most trouble.”5 Opposing White was Spud Chandler, 16-5 during the season. The 35-year-old veteran had squelched a Cardinals rally in the first game but not before being touched for two hits. He had suffered the Yankees’ only loss in the 1941 World Series against the Brooklyn Dodgers, losing Game Two.

Events in New York are often done on a grand scale and Game Three was no exception. The attendance of 69,123 was a record for a World Series game. In the crowd were New York Governor Herbert Lehman, his future successor Thomas Dewey, New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, and countless other politicians and celebrities. Baseball was represented by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, and Will Harridge and Ford Frick (presidents of the American and National Leagues respectively). Not to mention Babe Ruth.

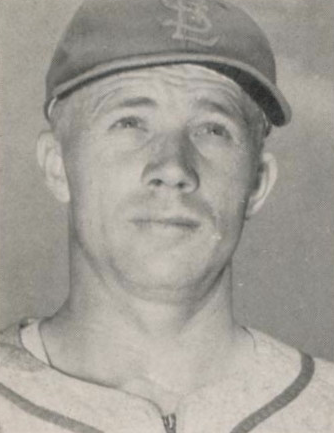

White pitched a shutout, scattering six hits over nine innings, striking out six and did not issue a walk. The Yankees’ only scoring threat came in the first inning when Phil Rizzuto made a bunt single, stole second, and went to third on a throwing error, only to be stranded when Joe DiMaggio struck out. From then on, no other Yankee got past first base.

St. Louis scored in the third when Kurowski received the only walk issued by Chandler. Marion laid down a bunt and was thrown out at first. The Yankees disputed the play, arguing that the ball had first bounced in the batter’s box and was thus foul. After arguments and deliberations, the umpires ordered Marion to bat again. He topped the ball down the third-base line and was safe at first. White sacrificed Kurowski and Marion up 90 feet. Jimmy Brown grounded to Joe Gordon at second and Kurowski scored.

The Cardinals got their second run in the ninth when Brown singled off Marv Breuer, who had relieved Chandler. Terry Moore bunted and both Cardinals were safe as Breuer’s errant throw on a force-play attempt pulled Rizzuto off second. The decision generated another eruption among the Yankees. Once again in this World Series Magerkurth, then in his 14th season as a National League umpire, was the focal point of a dispute.6Magerkurth called Brown safe after seemingly signaling that he was out. Instantly surrounded by protesting New Yorkers, the umpire held his ground and his call stood. Enos Slaughter singled Brown home. Moore reached third on another close play. Third baseman Frankie Crosetti was enraged by umpire Summers’ safe call at third.

As The Sporting News described it, Crosetti “gesticulated wildly and began shoving Summers around.”7After the Series Crosetti was fined $250 and suspended for the first 30 days of the 1943 season for his actions. The Yankees’ continued berating of the umpires could not have helped their cause over the course of the Series. Beginning in Game One, when McCarthy began to “bark” at Magerkurth over balls and strikes, a behavior continuing through the Series, the New Yorkers exhibited decidedly un-Yankee like demeanor.8 Tension on the club was palpable, something absent from their National League rivals.

After the dispute with Crosetti ended, Jim Turner relieved Breuer. Stan Musial was intentionally walked to load the bases with no outs. Walker Cooper flied out to shallow center and Moore held third. Turner then got Johnny Hopp to hit into an inning-ending double play. In the bottom of the ninth, White allowed a harmless single to DiMaggio before retiring the side, giving the Cardinals their second win of the Series. White had pitched the greatest game of his career.

While White received a great deal of praise, much of the attention centered on the Cardinals’ stunning play in the outfield. Moore, Musial, and Slaughter took the Yankees out of the game with spectacular catches. In the bottom of the sixth, with New York’s Roy Cullenbine on first and two outs, DiMaggio hit a long drive to left-center with Musial and Moore in pursuit. At the last second Moore lunged for and caught the ball. Observers felt that if he had not caught the ball DiMaggio would have had an inside-the-park home run.

In the seventh Joe Gordon hit a fly to deep left and Musial, with his back to the outfield wall, caught the ball over his head as it was about to leave the field. The next batter, Charlie Keller, smashed a pitch deep to right but Slaughter, leaping high, caught the ball against the right-field fence.9

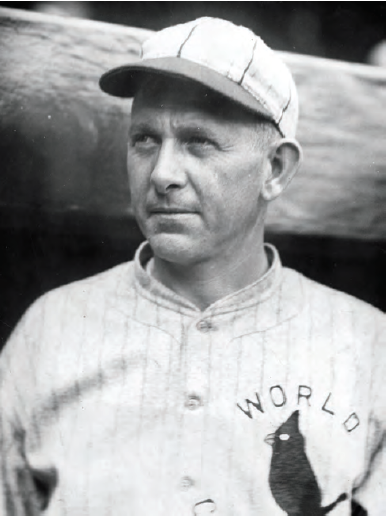

The Yankees were stunned. It was the first time they had been shut out in a World Series game since 1926, when the Cardinals’ Pop Haines accomplished that feat in Game Three. It was the first time since that same World Series that the Yankees had lost two games in a row. (The Cardinals’ victories were in Games Six and Seven.)

Although the big story on sports pages would continue to be the World Series, another narrative was developing that would have great effect on the Cardinals, as well as the Brooklyn Dodgers. On the same day as White’s victory, word came out that Sam Breadon, owner of the Cardinals, would allow the Dodgers to speak with Branch Rickey about joining their organization. Rickey’s contract as general manager with St. Louis expired at the end of 1942 and Brooklyn was looking to fill that position with Rickey after Larry MacPhail resigned to join the Army.

Rickey denied he was negotiating with Brooklyn. “I haven’t and if I had I wouldn’t say anything about it but I haven’t,” the St. Louis general manager said.10Under Rickey, general manager of the Cardinals since 1919, the team had won six pennants. Only the New York Giants (seven) could claim as many in that span.

That Rickey would be leaving the Cardinals was old news. Over a year earlier, J. Roy Stockton revealed in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that Rickey’s contract would not be renewed.11 He and Breadon had come to a parting of the ways. In 1938 Commissioner Kenesaw Landis had ruled that some of Rickey’s minor-league player transactions were improper and made 74 farmhands free agents, embarrassing Breadon. This and Breadon’s resentment of Rickey’s $50,000 salary plus commissions on player deals factored into his deciding to let Rickey go.

During the ensuing months rumors flew as to where Rickey might land once leaving the Cardinals. Some sources said the American League St. Louis Browns; others had him going to the Detroit Tigers.12Despite Rickey’s denials, word of his being allowed to negotiate with Brooklyn was accurate. Once Rickey moved to the Dodgers, the club rose to dominance of the National League in the 1940s and ’50s and a decline in the Cardinals’ eminence.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 “Spud Chandler and Ernie White Selected to Pitch Series Game at Stadium Today,” Details of the train trip were also outlined in The Sporting News. See Fred Lieb, “Clubs Use Same Train,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1942: 6. Lieb’s article says the train had 19 cars.

2 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: Avon Books, Inc., 2000), 244-245.

3 “Spud Chandler and Ernie White,” Hartford Courant, October 3, 1942: 9.

4 Mike Richard, “Ernie White,” SABR BioProject, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/b505a3b0.

5 “Spud Chandler and Ernie White,” Hartford Courant, October 3, 1942: 9.

6 “Cards Make Only Five Assists, Milkman Turner Unsung Hero,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1942: 15.

7 Ibid.

8 “Gossip of First Game,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1942: 3.

9 “Blow That Beat Bonham Foul – McCarthy,” The Sporting News, October 8, 1942: 14; Jack Cavanaugh, Season of ’42: Joe D, Teddy Ballgame, and Baseball’s Fight to Survive a Turbulent First Year of War (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2012), 248-249. Various accounts of the game, particularly in The Sporting News, have errant accounts of when these catches took place during the game.

10 “Rickey Conference Permitted Dodgers,” New York Times, October 4, 1942: S9.

11 J. Roy Stockton, “Rickey to Leave Cards? Way Paved for Move after 1942,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 20, 1941: 15.

12 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 318.

Additional Stats

St. Louis Cardinals 2

New York Yankees 0

Game 3, WS

Yankee Stadium

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.