September 12, 1914: Yankees hurler Ray Keating caught red-handed; American League bans emery ball

The inventor of the emery ball, former New York Highlanders/Yankees pitcher Russ Ford, did his best to keep his trick pitch a secret. He began using it in the American League in 1910 and for a while the competitive advantage was all his.1 But teammate Earle Gardner figured out what Ford was up to and he eventually let the cat out of the bag.2 Word quickly spread within the league. By 1914 the emery ball had become commonplace in the junior circuit.3

The inventor of the emery ball, former New York Highlanders/Yankees pitcher Russ Ford, did his best to keep his trick pitch a secret. He began using it in the American League in 1910 and for a while the competitive advantage was all his.1 But teammate Earle Gardner figured out what Ford was up to and he eventually let the cat out of the bag.2 Word quickly spread within the league. By 1914 the emery ball had become commonplace in the junior circuit.3

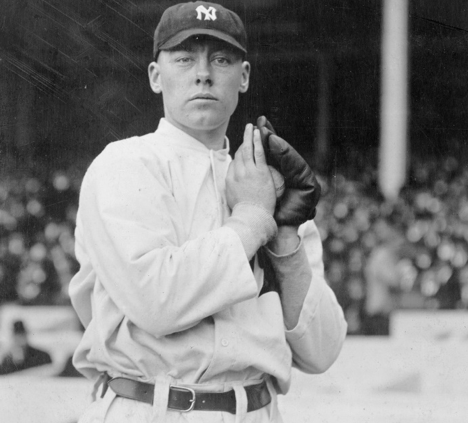

Fans had no clue what was going on – until Yankees hurler Ray Keating was caught red-handed throwing the emery ball in his September 12, 1914 start against the Philadelphia Athletics.4

New York had purchased Keating’s contract in May 1912 from the Lawrence (Massachusetts) Barristers of the New England League shortly after he tossed a no-hitter against the Worcester Busters.5 The $7,000 price tag was reportedly the largest sum ever paid for a player in the Class B circuit.6

The 19-year-old right-hander made his big-league debut once the New England League season ended, posting a 5.80 ERA in six September appearances with New York.7 He followed that up with an uninspiring 6-12 record in 1913.

After Ford jumped to the Federal League for the 1914 season, his former catcher, Ed Sweeney, taught Keating how to throw the emery ball.8 But unlike Ford, Keating didn’t bother disguising the pitch by pretending to load up a spitball, which was legal at the time.9

Despite throwing both an emery ball and a spitter, Keating continued to have mediocre results. Coming into his matchup against the Athletics, the native of Bridgeport, Connecticut, had a 4-10 record and a 3.05 ERA.10

The lowly Yankees were in seventh place with a 59-73 mark, leaving them a distant 27½ games behind the first-place Philadelphia Athletics. They were still in search of their first pennant since joining the AL in 1903. Even the addition of celebrated player-manager Frank Chance in 1913 had failed to turn the Yankees’ fortunes around, and they were headed for their fourth consecutive finish in the second division.11

The mighty Athletics, World Series champions in three of the four previous seasons, held an eight-game lead over the second-place Boston Red Sox with less than a month remaining in the season.12 Philadelphia’s high-powered offense, which was easily the AL’s best, was led by future Hall of Famer Eddie Collins. The 27-year-old was in the prime of his career and he led the league with a .355 batting average.13

Philadelphia manager Connie Mack gave the start to his ace, Charles Bender (15-2, 2.52 ERA).14 The 30-year-old righty came into the game having won his last 14 decisions, leaving him only two wins away from tying the AL record.15

After Keating retired the first two batters of the game, he ended the inning by striking out Collins.

Just before and after taking strike three, the Philadelphia second baseman complained to home-plate umpire Tommy Connolly that Keating was scuffing the baseball.16 According to Connolly, Collins had seen Smoky Joe Wood of the Boston Red Sox use the emery ball in a game in a Philadelphia.17 The incident would have been fresh in Collins’s mind, because Wood’s only appearance of the year at Shibe Park was just one day earlier.

Connolly and Collins checked the ball and found something suspicious. Connolly then inspected Keating’s glove and found a one-inch-square piece of emery paper in the hollowed-out palm. The umpire confiscated the emery paper, although Keating remained in the game.18

Mack was upset that Keating was permitted to continue pitching, so he informed Connolly that the Athletics were playing the game under protest.19 “I can’t keep on examining his glove every few minutes,” reasoned Connolly.20 It is not known if Keating threw any more emery balls in the game.

Since the pitch was not explicitly forbidden, Connolly was in a difficult spot. The only pertinent entry in the rulebook imposed just a $5 fine for intentionally damaging a ball.21

An inning later, the Athletics loaded the bases with nobody out. But New York third baseman Fritz Maisel caught Rube Oldring’s line drive and took one step to the bag for an unassisted double play.22 Keating escaped the inning unscathed by retiring catcher Wally Schang on a groundout.

In the third, Keating struck out Collins a second time. It was only the third time all season that Collins had struck out more than once in a game.23

Although Bender struggled through the first four innings, he still managed to keep New York off the scoresheet. The Yankees put runners on second and third with one out in each of the first two innings, but they came up empty both times. In the fourth, New York loaded the bases with two out before Bender buckled down and struck out Maisel to end the threat.24 The Yankees stranded seven runners on base in the first four innings.

The game settled into a tight pitchers’ duel.

With one out in the eighth, New York right fielder Doc Cook doubled down the left-field line, breaking Bender’s string of 11 consecutive outs. The next batter, former Athletic Tom Daley, got revenge on his former team by lacing a line-drive single that knocked Cook in with the game’s first run.25

Keating limited Philadelphia to three harmless singles from the third inning to the eighth.

The Athletics finally broke through against Keating in the ninth. With two out and Stuffy McInnis on first, Amos Strunk singled “through Maisel.”26 When the throw came home, Strunk continued on to second and Sweeney threw the ball well over the head of shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh and into center field. McInnis trotted home, tying the score, 1-1.27

Sweeney led off the bottom of the ninth with the “taunts of the multitude ringing in his ears.”28 He quickly turned the jeers to cheers by slamming the second pitch he saw from Bender into the right-field stands for a dramatic walk-off homer.29 Hundreds of fans swarmed the field as Sweeney rounded the bases.

Bender took the loss, snapping his winning streak at 14. Collins failed to get the ball out of the infield and went hitless in four at-bats.

After the game, Connolly sent two baseballs that he had taken out of play – each with a round, fuzzy spot about the size of a quarter – to AL President Ban Johnson, along with the confiscated piece of emery paper.30 It was left to Johnson to decide on the legality of the trick pitch.

According to one report, all of the Yankees pitchers had been experimenting with the emery ball, and Keating, Ray Fisher, Carroll “Boardwalk” Brown, and Cy Pieh had all mastered the pitch.31

After a heated postgame argument with the two Yankees owners, Bill Devery and Frank Farrell, Chance abruptly resigned as Yankees manager.32 There were several bones of contention, one of which was Chance allowing Keating to throw the emery ball.33

Chance cited interference from “grandstand managers” Devery and Farrell as the reason for his departure.34 Three days later, once Chance’s settlement terms were finalized, Peckinpaugh took over the managerial duties for the remainder of the season.35

On September 19, just before Keating’s next start, the Yankees were informed that Johnson had banned the emery ball.36 The penalty instituted for throwing the pitch was stiff: a $100 fine and a 30-day suspension.37

The Yankees went 10-10 with the 23-year-old Peckinpaugh at the helm, nudging them into a sixth-place tie with the Chicago White Sox.38 The Athletics finished 8½ games ahead of the second-place Red Sox to claim their fourth pennant in five seasons.39

Collins was overtaken in the batting race by a red-hot Ty Cobb, who hit .416 from September 12 to the end of the regular season.40 But Collins easily won the Chalmers Award as the American League’s most valuable player, leading the junior circuit in runs scored (122) and coming in second in batting average (.344), on-base percentage (.452), and stolen bases (58).

Keating spent three more undistinguished seasons in the big leagues before becoming a mainstay in the Pacific Coast League. The PCL, along with the American and National Leagues, finally outlawed the spitball in 1920, although each league grandfathered in a group of hurlers who could continue to throw the pitch. Keating was one of the pitchers on the PCL’s list.41

He enjoyed his best years in the PCL in 1927-28 when he won a combined 47 games for the Sacramento Senators. But in January 1932 Keating was released by the Seattle Indians, seemingly ending his professional career.

Burleigh Grimes hung on to become the last pitcher to legally throw the spitball in the National or American League, although by the middle of the 1934 season it had become apparent that his career was nearing its conclusion.42 In August of that year, Keating made a surprising − and brief – comeback attempt with Seattle. The 41-year-old, still a grandfathered spitball pitcher in the PCL, used the trick pitch to compile a respectable 3.97 ERA in six relief appearances.43

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org. Unless otherwise noted, all play-by-play information for this game was taken from the article “Sweeney’s Homer Beats Athletics,” on page 31 of the September 13, 1914, edition of the New York Times.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYA/NYA191409120.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1914/B09120NYA1914.htm

Photo credit

Photo of Ray Keating courtesy the Library of Congress.

Notes

1 Ford used the emery ball in 1910 to record one of the greatest rookie seasons in major-league history. He went 26-6, posted a 1.65 ERA, and struck out 209 batters. He jumped to the Federal League in 1914, along with fellow emery ball specialist Cy Falkenberg. T. Kent Morgan and David Jones, “Russ Ford,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Russ-Ford/, accessed March 20, 2023.

2 Ford began throwing the emery ball in games when he was with the Jersey City Skeeters in 1909. Gardner and Ford were teammates in Jersey City in 1909 and in New York with the Highlanders (1910-12). Gardner told Cy Falkenberg, his teammate on the 1912 Toledo Mud Hens, about the emery ball. Falkenberg had a breakout season with Toledo, going 25-8 in 1912. The 33-year-old returned to the big leagues with the Cleveland Naps in 1913, using the emery ball to go 23-10 with a 2.22 ERA. Dan Daniel, “Over the Fence,” The Sporting News, September 15, 1954: 1.

3 Russell W. Ford, “Russell Ford Tells Inside Story of the ‘Emery’ Ball After Guarding His Secret for Quarter of a Century,” The Sporting News, April 25, 1935: 5.

4 “No More Is the Sand Paper Ball,” Pine Bluff (Arkansas) Daily Graphic, September 27, 1914: 5.

5 “Ray Keating Secured by New York Americans; Local Boy Will Join Yankees at Close of Lawrence Season,” Bridgeport (Connecticut) Times and Evening Farmer, May 27, 1912: 8.

6 The $7,000 paid to acquire Keating in 1912 was worth over $200,000 in 2022 dollars after adjusting for inflation. “Yankees Pay $7,000 for Pitcher,” New York Times, May 30, 1912: 9.

7 Keating’s big-league debut was on September 12, 1912. He pitched a scoreless inning of relief against the St. Louis Browns.

8 Daniel, “Over the Fence”; Robert L. Ripley, “About Trick Pitching,” Boston Globe, July 13, 1918: 5; Harry F. Pierce, “Keating’s Use of ‘Emery Ball’ Precedes Squabble Resulting in Resignation of Chance,” St. Louis Star and Times, September 24, 1914: 10.

9 “Pitcher Russell Ford First to Use Emery Ball,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Star-Independent, September 23, 1914: 8.

10 The league-wide ERA was 2.73 in 1914.

11 Chance made his major-league debut in 1898. He was player-manager of the Chicago Cubs from 1905 until 1912, leading them to four pennants and two World Series championships.

12 Philadelphia had been 12½ games in front of Boston on September 2, but the Athletics were swept by the Red Sox in a four-game series at Fenway Park in early September to tighten up the race. Fortunately for the Athletics, they had wrapped up their season series with Boston. The Red Sox were the only team to have a winning record against Philadelphia in 1914; Boston won 12 of 21 games between the two teams.

13 Collins was also leading the league in runs scored (110) and on-base percentage (.464).

14 In Bender’s five previous starts against the Yankees in 1914, he had gone 3-0 with three shutouts. Bender made only four more appearances with the Athletics after this game. He jumped to the Federal League for the 1915 season.

15 At the time, the AL record was jointly held by Walter Johnson and Smoky Joe Wood. Both pitchers won 16 consecutive decisions in 1912. As of the end of the 2022 season, Carl Hubbell of the New York Giants held the National/American League record with 24 straight wins in 1936-37.

16 The author found surprisingly few references to Keating’s emery ball in newspapers the day after this game. A story published in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and several other newspapers on September 13-14 indicated that Collins complained to Connolly after his first-inning strikeout and the emery paper was found in Keating’s glove at the end of the top of the first. An article in the St. Louis Star and Times on September 20 claimed that the controversy erupted in the eighth inning, although Collins did not bat in the eighth. A story written by American League umpire Billy Evans appeared in several newspapers in November; it indicated that Keating was not found out until the third inning, when Collins struck out for the second time. It is worth noting that Evans did not work the Yankees-Athletics game on September 12; he was umpiring in St. Louis that day. “Keating’s ‘Emery Ball’ to Be Investigated,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 13, 1914: 17; Pierce, “Keating’s Use of ‘Emery Ball’ Precedes Squabble Resulting of Resignation of Chance”; Billy Evans, “Diamond Tales from Billy Evans,” Indianapolis Star, November 9, 1914: 9.

17 “Keating’s ‘Emery Ball’ to Be Investigated.”

18 “Keating’s ‘Emery Ball’ to Be Investigated.”

19 United Press, “Emery Ball May Be Like Dum-Dum,” Birmingham (Alabama) News, September 13, 1914: 9; “Keating’s ‘Emery Ball’ to Be Investigated.”

20 “Keating’s ‘Emery Ball’ to Be Investigated.”

21 Francis C. Richter, ed., The Reach Official American League Base Ball Guide, (Philadelphia: A.J. Reach Company, 1914), 382.

22 Heywood Broun, “Home Run by Sweeney Gives Yankees Game,” New York Tribune, September 13, 1914: 12.

23 This was the only game all season in which Collins struck out more than once in less than five plate appearances. “Eddie Collins | Player Batting Game Stats Finder,” Stathead.com, https://stathead.com/tiny/hNWec, accessed March 23, 2023.

24 Maisel finished the season with a .239 batting average and a league-leading 74 steals.

25 Three months earlier, Daley had been traded to the Yankees for outfielder Jimmy Walsh.

26 McInnis reached first when his grounder forced Frank “Home Run” Baker at second base. Baker had singled with one out. Broun, “Home Run by Sweeney Gives Yankees Game.”

27 “Big Sweeney Stars in Dual Capacity,” New York Sun, September 13, 1914: 16; Broun, “Home Run by Sweeney Gives Yankees Game.”

28 “Sweeney’s Homer Beats Athletics,” New York Times, September 13, 1914: 31.

29 “Mackies Bow to Sweeney’s Awful Smash,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 13, 1914: 41; “Big Sweeney Stars in Dual Capacity.”

30 “Keating’s ‘Emery Ball’ to Be Investigated”; United Press, “Emery Ball May Be Like Dum-Dum.”

31 “Ban Bars Emery Ball,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Daily Globe, September 21, 1914: 7.

32 Bill Lamb, “Bill Devery,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bill-devery/, accessed March 22, 2023.

33 Pierce, “Keating’s Use of ‘Emery Ball’ Precedes Squabble Resulting of Resignation of Chance.”

34 The ugly postgame incident between Chance and the Yankees owners “greased the skids for the departure of Frank Farrell and Bill Devery from the game.” On January 30, 1915, the Yankees were sold to Jacob Ruppert and Tillinghast “Til” Huston. In the 12 seasons that Farrell and Devery owned the team, the Highlanders/Yankees won no pennants and compiled a .479 winning percentage. Lamb, “Bill Devery”; “Chance Resigns as the Manager of Highlanders,” New York Evening World, September 12, 1914: 1.

35 “Chance Bids the Yankees Farewell,” New York Tribune, September 16, 1914: 8.

36 “Ban Bars Emery Ball.”

37 Evans, “Diamond Tales from Billy Evans.”

38 Peckinpaugh was the youngest manager in the American or National League in the twentieth century.

39 Philadelphia was swept in the World Series in stunning fashion by Boston’s “Miracle Braves.”

40 It was Cobb’s eighth consecutive batting title.

41 Brian McKenna, “Frank Shellenback,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/frank-shellenback/, accessed March 24, 2023.

42 Grimes pitched in his final major-league game on September 20, 1934. Harry Grayson, “By Harry Grayson,” Waterbury (Connecticut) Evening Democrat, July 25, 1934: 14.

43 Frank Shellenback was the last pitcher to legally throw a spitball in the minor leagues. He pitched in the PCL until 1937, when he was 38 years old. McKenna, “Frank Shellenback.”

Additional Stats

New York Yankees 2

Philadelphia Athletics 1

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.