September 26, 1906: Honus Wagner’s hitting, fielding overshadow Lefty Leifield’s darkness-shortened no-hitter

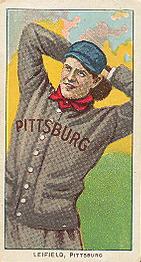

Pitching on a staff with three established 30-something stars and sharing a dugout with the league’s best player, the Pittsburgh Pirates’ 22-year-old southpaw Lefty Leifield probably recognized that copy would be hard to find during the 1906 season, but not this difficult. After Leifield tossed a darkness-shortened six-inning no-hitter against the Philadelphia Phillies on September 26, the Philadelphia Inquirer boasted that “[Honus] Wagner’s all-around playing in the game was the feature,”1 while newspapers from the Smoky City made nary a mention of Leifield’s name in accounts of the game.

Pitching on a staff with three established 30-something stars and sharing a dugout with the league’s best player, the Pittsburgh Pirates’ 22-year-old southpaw Lefty Leifield probably recognized that copy would be hard to find during the 1906 season, but not this difficult. After Leifield tossed a darkness-shortened six-inning no-hitter against the Philadelphia Phillies on September 26, the Philadelphia Inquirer boasted that “[Honus] Wagner’s all-around playing in the game was the feature,”1 while newspapers from the Smoky City made nary a mention of Leifield’s name in accounts of the game.

Concluding the season with 19 of their last 20 games on the road, the Pirates were scuffling when they arrived in the City of Brotherly Love to take on the fourth-place Phillies. Player-manager Fred Clarke’s third-place squad lost the first of the four-game set, 4-3, the 12th loss in their last 18 games, to fall to 87-55. They had not been within 10 games of the first-place Chicago Cubs since August 11. The Phillies, on the other hand, were playing inspired ball for skipper Hugh Duffy, the former batting star of the 1890s. With 12 victories in 19 games, they improved to 68-75, and still possessed an outside shot to reach .500 with 10 games to play.

On a crisp, 70-degree, partly cloudy Wednesday afternoon, a crowd of 2,596 came out for a twin bill at the Baker Bowl, the Phillies bandbox ballpark located on North Broadway. Some might have questioned sarcastically whether Phillies batters showed up.

In the first contest future Hall of Famer Vic Willis shut out the Phillies on six hits for his 22nd victory. In his first season with the Pirates after eight seasons with the Boston Braves, Willis reached the 20-win mark for the fifth of eight times in his career.

On the slab for the Bucs in the second game was Leifield, a 6-foot-1, 165-pound string bean in his first full season. According to Lenny Jacobson in Leifield’s SABR biography, Pittsburgh’s starter relied on excellent control for his success, instead of a single devastating pitch.2 Sportswriters John J. Evers and Hugh S. Fullerton reported that Leifield “seldom uses curves unless compelled to, and his fast ball which breaks with an odd little jump, is one of the hardest for batters to hit.”3

After breezing through a September call-up the previous year, going 5-2, Leifield emerged as a bona fide ace on a staff with three of them. In addition to Willis, two hurlers from the club’s 1903 World Series championship team still commanded respect: Sam Leever, en route to his fourth 20-win campaign in the last eight years, and Deacon Phillippe, with six 20-plus-win seasons on his docket. Leifield entered the game with a 17-11 slate and a team-high seven shutouts, among them a two-hitter, three five-hitters, and a yeoman, 13-inning blanking.

But his best outing in 1906 had resulted in a loss. In the afternoon game of an Independence Day twin bill in Chicago, Leifield held the Cubs without a baserunner through eight innings before Jimmy Slagle led off the ninth with a single in rainy conditions, and eventually scored as a result of an error.4 Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown also tossed a one hitter — Leifield connected for the only hit — and won, 1-0.

Leifield was not as sharp in this contest in Philadelphia as he was in the Windy City. Through six innings, he yielded two walks and had Wagner to thank for his abbreviated no-no. “The big Dutchman fielded in wonderful style,” reported the Inquirer, “and killed off at least two hits.”5 In the second inning, the 5-foot-11, 200-pound fleet-footed shortstop raced into left field and snared Paul Sentell’s fly over his shoulder while sprinting with his back to the grandstand, according to the Pittsburgh Press.6 Three innings later, Wagner made what the Press called a “remarkable pick up” on Ernie Courtney’s hard grounder and tossed to first.

“While Leibield [sic] was playing with the Phillies, the Pirates were hammering [Walter] Moser,” observed the Inquirer.7 A 25-year-old rookie right-hander, Moser was searching for his first big-league win in his fifth career appearance and third start since his acquisition from the Lynchburg Shoemakers in the Class C Virginia League, where he had won 24 games. Moser benefited from a “neat double play” in the first inning, noted the Pittsburgh Gazette-Times.8 Replacing Clarke, who had injured his leg prior to the twin bill and missed both games,9 Dutch Meier lofted one to right field where Johnny Lush snared it and then fired a strike to first to catch Bob Ganley, who apparently thought the ball would fall.10 The 20-year-old Lush was a budding two-way star, en route to 18 wins on the mound while making 21 starts in the outfield in his first full season.

“Wagner was at his best,” raved the Pittsburgh Post, and was seemingly involved in all pivotal action in this game. The 32-year-old, 10-year veteran was still at the top of his game. Hans, as newspapers liked to call him, was closing in on his fourth batting title (and would capture four more in the next five years). He led off the second by beating out an infield hit and moved up on Joe Nealon’s sacrifice. Moser fielded Tommy Leach’s bunt, but instead of going for a sure out at first, tossed too late to third to erase Wagner. Bill Abstein’s fly out was deep enough to plate Wagner for the first run.

Though the Phillies committed only one official error, the Inquirer declared that the team’s “poor fielding and inability … to field bunts hit toward the first base gave the Pirates the game on a silver platter.”11 The Pirates tallied three more runs in “easy fashion” in the third, wrote the Gazette-Times.12 With two outs, consecutive singles by Ganley, Meier, and Wagner produced the first of those. With Nealon at the plate, Wagner pilfered second. When Meier charged home in what appeared to be a delayed double steal, shortstop Mickey Doolin returned the throw home, but the ball sailed over catcher Red Dooin’s head. Meier scored and Wagner raced around to score, too, to make it 4-0.13

The Phillies’ poor defense contributed to the Pirates’ four-run outburst in the fifth. Second baseman Kid Gleason fumbled Bill Hallman’s leadoff grounder. Hallman took third on Moser’s wild pitch and scored on Ganley’s single. After Meier bunted safely, Wagner walked (perhaps intentionally) to load the bags. Nealon’s single drove in two more. In relentless Deadball Era style, Leach laid down a sacrifice bunt, advancing both Wagner and Nealon. Abstein’s deep fly drove in Wagner, his third run of the game, to give the Pirates an 8-0 lead.

With the Pirates comfortably ahead after six innings, umpire Hank O’Day called the game because of darkness. Leifield was credited with a no-hitter to complete the doubleheader shutout, but the Pirates offense – which had collected nine hits in each game – was the focus of Pittsburgh newspapers. Ganley collected five hits and scored three runs; filling in ably for Clarke, Meier also had five hits, and Wagner had four hits and two walks, and scored four times.

Leifield finished the season with an 18-13 record and the league’s fifth-best ERA (1.87). His eight shutouts trailed only Three Finger Brown’s nine. He emerged as a solid starter, averaging 17 wins for the Pirates over the next five seasons (1907-1911). He subsequently suffered arm problems, was out of the big leagues after the 1913 season, and had a comeback with the St. Louis Browns (1918-1920). He flirted with a no-hitter on August 19, 1919, holding the visiting Boston Red Sox hitless until a seventh-inning single, and finished with a one-hitter.

Leifield won 124 games and tossed 32 shutouts in his 12-year big-league career. For 85 years his name was counted among those who authored a no-hitter; however, that changed in 1991 when Commissioner Fay Vincent convened and chaired the Committee for Statistical Accuracy. It amended the definition of a no-hitter to include only those games that last at least nine innings and end with no hits. An estimated 36 abbreviated no-hitters were removed from the ranks, included Leifield’s.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and SABR.org.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/PHI/PHI190609262.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1906/B09262PHI1906.htm

Notes

1 “Phillies Drop Double Header,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 27, 1906: 10.

2 Lenny Jacobson, “Lefty Leifield,” SABR BioProject. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/lefty-leifield/.

3 John J. Evers and Hugh S. Fullerton, Touching Second (1910), quoted from Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Fireside, 2004), 278.

4 “Pirates Blanked in Double Header,” Pittsburgh Post, July 5, 1906: 10.

5 “Phillies Drop Double Header.”

6 “Phillies Are Twice Blanked,” Pittsburgh Press, September 17, 1906: 14.

7 “Phillies Drop Double Header.”

8 “Phillies Blanked in Both Games,” Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, September 27, 1906: 8.

9 “Pirates Hand Out Double Goose-Egg,” Pittsburgh Post, September 27, 1906: 10.

10 “Phillies Blanked in Both Games.”

11 “Phillies Drop Double Header.”

12 “Phillies Blanked in Both Games.”

13 “Phillies Blanked in Both Games.”

Additional Stats

Pittsburgh Pirates 8

Philadelphia Phillies 0

6 innings

Game 2, DH

Baker Bowl

Philadelphia, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.