September 8, 1960: Minneapolis Millers face St. Paul Saints for final time at Metropolitan Stadium

On a cool 1960 September evening in Bloomington, Minnesota, one of the greatest rivalries in minor-league baseball came to an end.

On a cool 1960 September evening in Bloomington, Minnesota, one of the greatest rivalries in minor-league baseball came to an end.

But nobody knew.

When the St. Paul Saints visited Metropolitan Stadium to play the Minneapolis Millers on September 8, little did anyone know that it would be the last game ever between the two teams and the last American Association game to be played there.

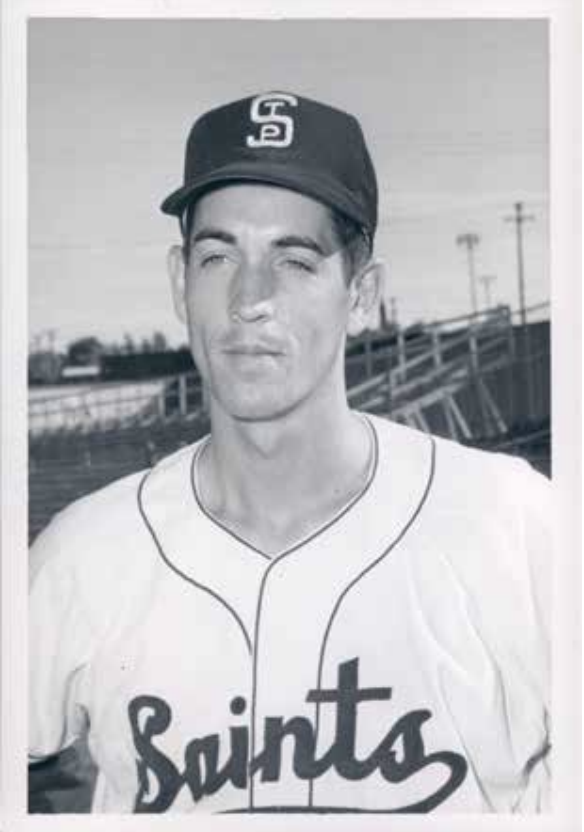

For the record, Saints starter Jim Golden, pitching in the evening game of a doubleheader, won his 20th game of the season, allowing only four hits and three walks in a 7-0 Saints victory.

The Saints finished the season with an 83-71 record and lost four games to two to Louisville in the postseason playoffs.

The Millers finished the season by winning one of three games at Houston and finishing with a fifth-place record of 82-72.

But the real end of the season occurred at a meeting of major-league owners on October 26, at which they allowed the Washington Senators to move to Minnesota for the 1961 season.

While that was great news for fans who had tried for the previous decade to lure major-league baseball to the Twin Cities, it marked the end of the line for both the Millers and the Saints and, with it, a storied rivalry.

The two teams were separated by the Mississippi River and the great loyalty of their fans … nearly equaled by dislike for one another.

Nicollet Park, just off the busy intersection of Lake Street and Nicollet Avenue in south Minneapolis, and Lexington Park, the Saints home at Lexington and University Avenues, were separated by just several miles and a 30-minute streetcar ride.

A sign of the pride and competition between the cities was that the streetcar journeyed over the Lake Street Bridge unless you were from St. Paul, in which case the ride took you over the river on the Marshall Avenue Bridge. It was actually the same bridge … only the names were changed to preserve the rivalry.

Tom Mee, the public-relations director for both the St. Paul Saints and the Minnesota Twins, frequently referred to the rivalry as “probably the shortest road trip in professional baseball.”

Both cities built new ballparks in the mid-1950s, motivated by the need to modernize and the fact that neither city would ever get major-league baseball without a modern ballpark.

Meanwhile, the leaders of the Minneapolis effort purchased farmland in Bloomington, just off Cedar Avenue and what was to become Interstate 494. Metropolitan Stadium opened in 1956 with a seating capacity of 18,200, but with the possibility of adding enough seating to more than double its capacity. Eventually the ballpark had more than 45,000 seats, allowing it to host professional football on a field that ran north to south between the third-base line and the right-field bleachers. The Millers drew an impressive crowd of 18,366 for their inaugural game against Wichita.

For St. Paul that new ballpark turned out to be Midway Stadium, located on Snelling Avenue, south of the Minnesota State Fair Grounds. It opened in 1957 with a seating capacity of 10,250 and an Opening Day crowd of 10,169.

The distance between the two new ballparks was 10.7 miles.

In a competition that ran from 1902 to 1960, the Saints held a 679-626 advantage over the Millers.

As the highest level of minor-league baseball, both the Millers and the Saints featured an array of promising rookies and longtime veterans either on the last legs of their career as players or on the start of careers as managers or coaches.

The outfield trio of Willie Mays, Ted Williams, and Carl Yastrzemski led a list of Millers who eventually were elected into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Other Millers Hall of Famers were Roger Bresnahan, Jimmy Collins, Rube Waddell, Red Faber, Bill McKechnie, Zack Wheat, George Kelly, Billy Herman, Ray Dandridge, Hoyt Wilhelm, Monte Irvin, Orlando Cepeda, Dave Bancroft, and Jimmie Foxx.

Likewise, St. Paul had its share of future Hall of Famers, led by Duke Snider and Roy Campanella. That list also has Charles Comiskey, Miller Huggins, Bill McKechnie, Leo Durocher, Lefty Gomez, Dick Williams, and Walter Alston.

The fact that McKechnie appears on both lists was not unusual. In fact, it was relatively common for players to move from one team to another, as was the case with first baseman Gail Harris, the former Millers slugger who was to play a key role in the final-game victory as a member of the Saints.

One of the highlights of the rivalry was the “split doubleheader,” in which where the teams would play an afternoon game in one park and an evening game in the other.

It was common for a brushback pitch in game one to be followed by a brawl in the second game. It was a classic case of neighbors not getting along well.

That final game at Met Stadium was part of a split doubleheader, but both games were at the Millers’ home field. The time between games allowed the home team to clear the ballpark and charge a separate admission to the season-ender.

For the host Millers, the 1960 season had been less than fulfilling. While the team performed well on the field, fans were not excited. The thrill of the new ballpark had diminished, and fans still resented the move of the New York Giants to San Francisco despite some flirtation with the Twin Cities.

Millers fans seemed less enchanted with being a Boston Red Sox farm club than a Giants Triple-A franchise, and the lack of enthusiasm was reflected in attendance.

Millers general manager George Brophy, in a midyear dispute over the local media’s fixation on dwindling crowds, had taken to not announcing daily attendance figures. Only after the final game did he reveal that annual attendance had dropped from 160,167 in 1959 to 115,702 in 1960. Major-league teams considering a move to the relatively virginal Midwest were unlikely to be impressed with an average attendance of 1,500 per game.

Each team had a personal interest in the final series. For the Saints it was a chance for Golden to win 20 games. For the Millers the question was whether Yastrzemski, successfully making the transition from second base to left field, could win the American Association batting title in a close race with Denver’s Bobo Osborne.

In addition, Yastrzemski was heading into the doubleheader with a 30-game hitting streak, the league’s longest of the season.

The baseball teams had substantial competition as the season neared its end. Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird was the number-one best seller, a new dance called the Twist was taking over dance floors, and nightly television reports from the Rome Olympics introduced Americans to a new sports hero, Wilma Rudolph.

The teams agreed on a shortened seven-inning first game, which the Millers won on a four-hit shutout behind 6-foot-6 right-hander Don Schwall, who was slotted into the parent Boston Red Sox pitching rotation in 1961, where he responded with a 15-7 won-lost record and a 3.22 earned-run average.

Crafty veteran Art Fowler of the Saints, 38 years old and 13 years removed from a stint as a Miller, held the Millers to just two hits in a losing effort. Fowler was to return to Met Stadium in 1969 as a pitching coach under new Twins manager Billy Martin.

Yastrzemski went 0-for-2 in the first game to end his hitting streak and followed that with an 0-for-4 performance in the night game.

The Saints pounded Millers pitching for 13 hits en route to a 7-0 victory in the nightcap. First baseman Harris, a stalwart of Millers lineups in the mid-1950s, went 2-for-4 with two home runs and two runs batted in. Center fielder Carl Warwick went 3-for-5 with two singles and a double, while Johnny Goryl, another former Miller, and a future Twins infielder, coach, and manager, chipped in with a single and a run scored.

Just three days earlier Golden had gone the distance in winning his 19th game.

“We were expected to finish what we started,” Golden recalled years later in an interview with the author. “We didn’t pay much attention to pitch counts. We did chart each game as to where pitches were hit and off of what kind of pitch.”

Golden also recalled another unusual aspect of the intercity series.

“We never went to the visitors clubhouse at Met Stadium,” he said. “We’d get together and dress at our home clubhouse at Midway Stadium. Then we’d take a bus to Metropolitan Stadium. After the game we would return to Midway to shower and change back into our street clothes.”

Miller Notes:

Yastrzemski finished second in the American Association batting race at .339 vs. Denver’s Osborne’s .342. Yastrzemski became Boston’s starting left fielder in 1961. He starred there for the next 23 years and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1989.

With the Twins moving to Met Stadium in 1961, Boston moved its Triple-A affiliate to Seattle, and the parent Dodgers moved the Saints to Omaha.

The Twins, in their first year in the majors, drew 1,256,723 fans, third best in the American League.

Golden, promoted to the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1960, appeared in one game that year and compiled a 9-13 major-league record over the next four years with the Dodgers and Houston, pitching mostly in relief.

Sources

Conversations with Tom Mee.

Author interview with Jim Golden, March 2020.

Additional Stats

St. Paul Saints 7

Minneapolis Millers 0

Metropolitan Stadium

Bloomington, MN

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.