100 years later, looking back at Ernie Shore’s ‘perfect game’

This article was written by John McMurray

This article was published in SABR Deadball Era newsletter articles

This article originally appeared in the SABR Deadball Era Committee’s February 2017 newsletter.

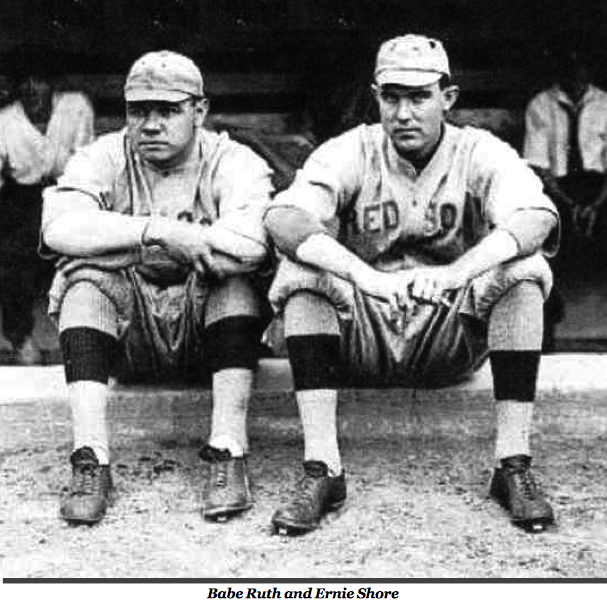

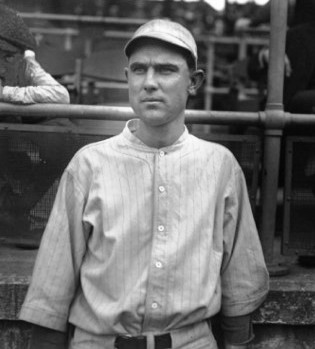

In early 1961, nearly 44 years after the event, Al Laney recalled Ernie Shore’s unique pitching achievement against the Washington Senators with a memorable opening line in the New York Herald Tribune: “On a Saturday in the summer of 1917 at Fenway Park in Boston, a tall, slim handsome young man settled down on the end of the Red Sox bench prepared for a long afternoon of idleness. A double header with Washington was on but it was not Shore’s turn to pitch.”

In early 1961, nearly 44 years after the event, Al Laney recalled Ernie Shore’s unique pitching achievement against the Washington Senators with a memorable opening line in the New York Herald Tribune: “On a Saturday in the summer of 1917 at Fenway Park in Boston, a tall, slim handsome young man settled down on the end of the Red Sox bench prepared for a long afternoon of idleness. A double header with Washington was on but it was not Shore’s turn to pitch.”

The events to follow have taken on the force of baseball legend. Boston starting pitcher Babe Ruth became agitated after walking Ray Morgan, Washington’s leadoff hitter; Ruth then confronted umpire Brick Owens about balls and strikes, suffering a swift ejection; Shore entered the game; and, after Morgan was caught stealing on the first pitch, Shore retired the next 26 batters consecutively, resulting in what would, for many years, be considered a perfect game.

The Shore game is likely the most remembered baseball event of 1917. Its only plausible challenger for the most remarkable moment of the season is the Red-Cubs double no-hit game which took place nearly two months earlier. Fred Toney of the Cincinnati Reds and Hippo Vaughn of the Chicago Cubs were untouchable in the only game in which neither team got a hit over nine innings. Yet, because of the never-to-be duplicated set of circumstances surrounding Shore’s achievement, Shore’s feat justifiably follows the Merkle Game in 1908 and Game Seven of the 1912 World Series as the most remembered of the Deadball Era.

Then 26 years old, Shore was anything but a pitching novice. Having pitched superbly in both the 1915 and 1916 World Series, Shore was already a formidable, if underrated, pitcher. But the understated Shore had the misfortune of being perpetually in the shadow of Babe Ruth, his onetime roommate. The renown that Shore would normally have received for winning both the opening and deciding games of the 1916 World Series was trumped by Ruth having pitched 13 shutout innings in Game Two, in what Hugh S. Fullerton wrote in the New York Times the next day was “the greatest world’s series game ever played, before perhaps the greatest crowd that ever saw one.” That Ruth was buoyed by great defense during Game Two or that Shore did not give up an earned run while pitching a complete game in the deciding Game Two are details which have been forgotten over time.

Today, as then, Shore’s performance on June 23, 1917 is seen first and foremost through the lens of Ruth. Even in Shore’s 1980 obituary in the New York Times, the two remained linked, with the headline “Ernie Shore; Pitched A Rare Perfect Game After Relieving Ruth” at least partially taking the spotlight away from the former Red Sox right-hander. In Babe: The Legend Comes To Life, Robert Creamer offered this summary of the dynamic:

“Shore pitched in the minor leagues with him at Baltimore and was a better pitcher then than the Babe; yet Ruth was adulated far more than Shore. When the two of them were sold together to the Boston Red Sox, newspaper comment of the day said that the transaction could not help but be a good one for the Red Sox because of Ruth. But with Boston it was Shore who moved right in as a starting pitcher, while Ruth faltered and was sent back to the minor leagues again for a time…

“In 1917 Shore pitched a perfect game, one of the rarest feats in baseball. The Babe started that game and was thrown out of it by the plate umpire before getting anyone out. Shore, sent hurriedly to the mound in Ruth’s place, did not allow anyone to reach base to reach base in the nine full innings that followed and was credited with a perfect game. Baseball fans are more aware of that game because of Ruth than because of Shore. Even then, on his biggest day in baseball, Shore’s solid accomplishment was overshadowed by the Babe’s personality.”

Accounts of Ruth’s clash with umpire Brick Owens outline the same general sequence of events but differ in the descriptions. In the Boston Globe game story published the next day, Ruth reportedly became agitated over two of the pitches called as balls during Morgan’s at-bat. “‘Get in there and pitch,’ ordered Owens. ‘Open your eyes and keep them open,’ chirped Babe. ‘Get in and pitch or I will run you out of there’ was the comeback of the arbiter. ‘You run me out and I will come in and bust you on the nose,’ Ruth threatened. ‘Get out of there now,’ said Brick.” The story then says that catcher Pinch Thomas (referred to in the article as ‘Chester Thomas’) tried to get in between Ruth and Owens, who was still wearing his mask, but that Ruth began “swinging both hands,” striking Owens with his right hand “behind the left ear.” Finally, “Manager [Jack] Barry and several policemen had to drag Ruth off the field.”

Accounts of Ruth’s clash with umpire Brick Owens outline the same general sequence of events but differ in the descriptions. In the Boston Globe game story published the next day, Ruth reportedly became agitated over two of the pitches called as balls during Morgan’s at-bat. “‘Get in there and pitch,’ ordered Owens. ‘Open your eyes and keep them open,’ chirped Babe. ‘Get in and pitch or I will run you out of there’ was the comeback of the arbiter. ‘You run me out and I will come in and bust you on the nose,’ Ruth threatened. ‘Get out of there now,’ said Brick.” The story then says that catcher Pinch Thomas (referred to in the article as ‘Chester Thomas’) tried to get in between Ruth and Owens, who was still wearing his mask, but that Ruth began “swinging both hands,” striking Owens with his right hand “behind the left ear.” Finally, “Manager [Jack] Barry and several policemen had to drag Ruth off the field.”

Creamer’s account uses entirely different dialogue: “‘Open your eyes!’ Ruth yelled. ‘Open your eyes!’ ‘It’s too early for you to kick,’ the umpire yelled back. ‘Get in there and pitch!’ Ruth stomped around the mound angrily, wound up and threw again. ‘Ball four!’ Owens snapped. Ruth ran in toward the plate. ‘Why don’t you open your god-damned eyes?’ he screamed. ‘Get back out there and pitch,’ Owens shouted, ‘or I’ll run you out of the game.’ ‘You run me out of the game, and I’ll bust you one on the nose.’ Owens stepped across the plate and waved his arm. ‘Get the hell out of here!’ he cried. ‘You’re through.’

“Ruth rushed him,” continues Creamer. “Chester Thomas, the catcher, got between the angry pitcher and the umpire, but Ruth swung anyway, over the catcher’s shoulder. He missed with a right, but a left caught Owens on the back of the neck. Ruth was in a frenzy, and Thomas and Jack Barry, who came running to the plate, had to pull him away from the umpire. A policeman came down from the stands and led the still fuming Ruth off the field.”

But Ruth’s account in his own autobiography, The Babe Ruth Story as told to Bob Considine, complicates matters further, as Ruth incorrectly refers to Eddie Foster as the first batter (Foster batted second), says that he threatened to punch Owens “on the jaw” (rather than the nose, as Creamer cited), and says that Thomas and other players dragged him off the field, without mentioning police intervention at all. Writing in Sports Illustrated in 1962, Mal Mallette said Ruth threw “a looping right-hand punch,” while noting that some said Ruth punched Owens on the jaw while others said that Ruth hit the umpire behind the left ear. Perhaps the only universally agreed-upon details are contained in one contemporary headline, which encapsulated the events succinctly: “Shore Is Not Hit; Umpire Is, by Ruth.”

But what is most unusual about the Shore game is that, for all the attention provided to the squabble with Ruth, the on-field action that followed is usually discussed in much less detail. Once again, Shore seems to have been dwarfed by baseball’s most renowned player and character. It is almost as if Shore’s performance, though efficient, did not have sufficient color to merit much more than platitudes or generalities. One representative example, the aforementioned story by Laney: “Allowed only five warm-up pitches, Shore went to work, and when he was done two hours later he had achieved that rarest of baseball feats, a perfect game.”

The vintage Globe account offers the most comprehensive account of the game’s action, saying:

“Ernie just breezed along calmly. He fielded his position well and was ready for any of those cantankerous bunts that the opponents might try to lay down but strange to say the Griffmen were off that stuff, relying mostly on the slam-bang system. The Carolinian is indebted to Scotty (shortstop Everett Scott) and Duffy Lewis for making his record. The Bluffton Kid robbed (Charlie) Jamieson of a hit in the fifth when a hard hit ball was deflected by Shore, Scotty being obliged to travel fast. However, he made a one hand pick-up and tossed out the runner.

“In the seventh, ‘Duff’ went back to his own little cliff for a bang from Morgan and in the final frame came in like lightning and speared one that (John) Henry had planted in short left. Shore fanned only two and it did not seem as if he was working hard. He made a number of nifty plays himself. Barry closed the game with a grand play on a swinging bunt by pinch hitter (Mike) Menosky. … When later asked about the propriety of a bunt—swinging or not—late in a no-hitter, Shore was unfazed, saying: “That’s the way (manager) Clark Griffith was. He never gave the opponents a thing.”

In a May 21, 1952 interview published in The Sporting News, Shore said: “I’ve never seen a more helpless team in baseball than Washington was that day. They hardly got the ball out of the infield all day.” Shore, though, said years later that his best game was a 13-inning, 1-0 victory against the Detroit Tigers in 1915. “If my fastball was breaking, I could beat anybody,” he said.

Originally considered a perfect game since Shore retired 27 consecutive batters after entering the game, including the one baserunner that he inherited, the game was later changed to a combined no-hitter following a re-evaluation by Major League Baseball in 1991 under Commissioner Fay Vincent’s direction. Given the question that persisted from the start of how Shore could have pitched a perfect game when he did not pitch a complete game, he said: “I don’t know what they meant when they said I didn’t pitch a complete game. But how complete is complete? You have to get 27 men out and I got 26 and the other was retired when I was pitching. No other pitcher retired a single batter.”

Just as Harvey Haddix would no longer be credited with a no-hitter in a game in which he allowed a hit, Shore would not be listed as a pitcher who threw a perfect game since one runner did reach base. Though no longer the third pitcher of the modern era, following Cy Young and Addie Joss, to pitch a perfect game, Shore noted that the novelty of the game itself would make his effort more well-remembered than the perfect game of, say, Charlie Robertson.

Just as Harvey Haddix would no longer be credited with a no-hitter in a game in which he allowed a hit, Shore would not be listed as a pitcher who threw a perfect game since one runner did reach base. Though no longer the third pitcher of the modern era, following Cy Young and Addie Joss, to pitch a perfect game, Shore noted that the novelty of the game itself would make his effort more well-remembered than the perfect game of, say, Charlie Robertson.

Following his retirement, Shore served as sheriff of Forsyth County in North Carolina, a position in which he served for 36 years. He was the first sheriff in North Carolina to equip police cars with two-way radios, according to the New York Times, and also became president of the State Sheriff’s Association. The baseball park in Winston-Salem, North Carolina was also named in Shore’s honor.

Laney reported in 1961 that the 69-year old Shore and “the slim young man of Fenway in front of whom life stretched so pleasantly in 1917 is the same.” Shore’s fame from baseball also extended into his post-playing life: “Practically everyone has heard of me,” said Shore. “If I have to pick up a prisoner in some remote spot, I generally get special treatment I wouldn’t get otherwise. People are always asking me about that game. I can’t say I really mind.” In the second game of that doubleheader, incidentally, Dutch Leonard pitched a complete game against Walter Johnson while the Senators got only four hits.

“Ernie Shore had pitched many a fine game for Boston, including World Series victories, but he never had and never would pitch another game such as this one,” said Laney. “Say his name anywhere that baseball is known about, and this one day at Fenway will spring to mind.” Perfect game or not, Shore’s remarkable performance from one-hundred years ago remains one of the most distinctive moments of the Deadball Era and, much like the Merkle game, offers a confluence of events that baseball fans surely will never witness again.

JOHN McMURRAY is chair of SABR’s Deadball Era Research Committee. Contact him at deadball@sabr.org.