1882 Winter Meetings: Reconciliation and Cooperation

This article was written by Michael McAvoy

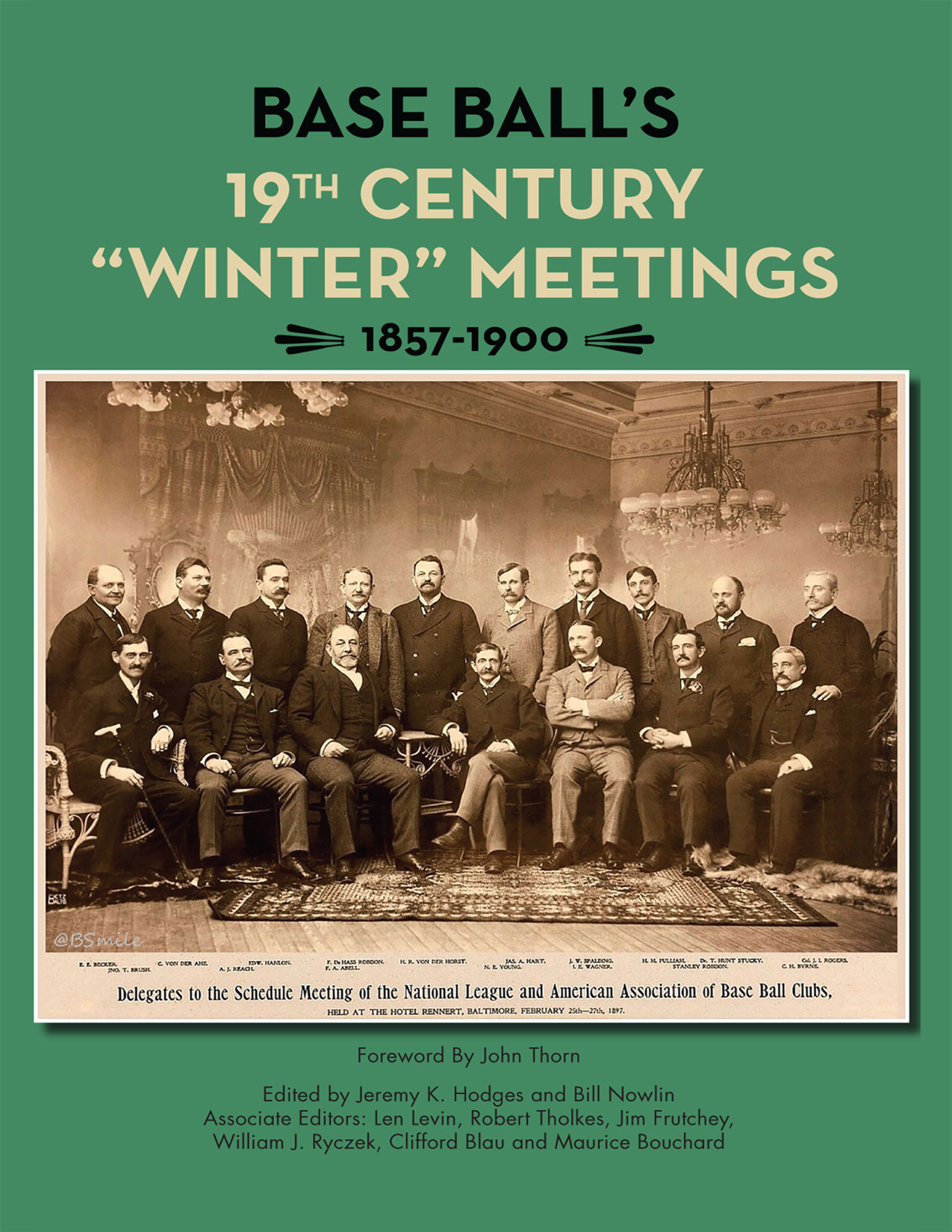

This article was published in Baseball’s 19th Century Winter Meetings: 1857-1900

Introduction

By contemporary accounts, the 1883 championship season was a grand success, noteworthy for the nationwide baseball boom, establishment of new professional joint-stock clubs, and organization of professional baseball associations. The offseason business meetings prepared professional baseball for an orderly championship season. No doubt this was due to a desire for the established National League (NL) to have a more prosperous relationship with the more financially successful American Association (AA).1 Under its new president A.G. Mills, the NL signaled this intention with better communication by appointing a conference committee to solve their differences. Importantly, the resulting Tripartite Agreement successfully organized the primary professional baseball associations and provided a model for how baseball organizations would in following seasons seek recognition within an organized framework. Such result did not have to be so, for the AA’s independence policy demonstrated to the NL that it might develop into a permanent competitor and claim to the best professional league.2

By contemporary accounts, the 1883 championship season was a grand success, noteworthy for the nationwide baseball boom, establishment of new professional joint-stock clubs, and organization of professional baseball associations. The offseason business meetings prepared professional baseball for an orderly championship season. No doubt this was due to a desire for the established National League (NL) to have a more prosperous relationship with the more financially successful American Association (AA).1 Under its new president A.G. Mills, the NL signaled this intention with better communication by appointing a conference committee to solve their differences. Importantly, the resulting Tripartite Agreement successfully organized the primary professional baseball associations and provided a model for how baseball organizations would in following seasons seek recognition within an organized framework. Such result did not have to be so, for the AA’s independence policy demonstrated to the NL that it might develop into a permanent competitor and claim to the best professional league.2

For clubs in member associations, the Tripartite Agreement recognized valid contracts, protected franchises and exclusive territories, extended the privilege of the reserve rule, and established the Arbitration Committee, a private regulatory body to settle the disputes between clubs in member associations. The agreement demonstrated that the NL adapted its mission to tolerate competing baseball associations. The AA gave up its opposition to the reserve rule in exchange for mutual recognition of contracts.

New Baseball Associations Enter the Professional Ranks

Prior to the AA and NL annual meetings, two new professional associations, the Northwestern League (NWL) and the Interstate Association (ISA), organized, developing club structure, protection policy, and a championship schedule. The successful completion of the AA’s 1882 championship season must have encouraged baseball entrepreneurs in places without an AA or NL franchise. Clubs in the new associations were interested in games with NL and AA clubs as well as the privilege of mutual recognition for contracts.

In August 1882, news spread that a new association would organize to offer a championship for the 1883 season for professional clubs in Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin.3 On October 27, 1882, club delegates met at Chicago’s Palmer House to organize the Northwestern League. The meeting adjourned to the first Wednesday after the second Tuesday in December, but instead met at Fort Wayne, Indiana, concurrent with the NL annual meeting.4

The Interstate Association organized on November 9, 1882, at a meeting in Reading, Pennsylvania, for clubs from Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The AA rules were adopted. The ISA formed a committee charged with recommending a membership request to the AA Alliance.5 At Philadelphia’s Girard House on November 25, a letter from the AA was read which endorsed the new association and informed that no clubs would be admitted from places with NL or AA clubs. Directors Eli B. Fox, T.B. Fielders, A.F. Richter, and Charles Waitt were delegated to represent the ISA at the AA meeting on December 13, 1882, in New York City. The ISA meeting was adjourned to December 16, 1882, at Girard House.6

The National League Board of Directors Meeting, December 5, 1882

The NL Board of Directors met on December 5, 1882, at the Hotel Dorrance in Providence, Rhode Island. For the directors, Arthur H. Soden (Boston), W.B. Thompson (Detroit), Freeman Brown (Worcester), A.H. Hotchkiss (Troy), and George H. Hughson (Buffalo), their first order of business was to award the 1882 championship to Chicago. Then the board heard — and rejected– an appeal from Herm Doscher, who had been expelled, and it unanimously endorsed the action by the Cleveland club.7

The National League Annual Meeting, December 6-7, 1882

The NL meeting featured franchise realignment, a new umpire system, some important rules changes, and the promise of an end to its conflict with the AA. Delegates from NL clubs met at the Hotel Dorrance in Providence over December 6-7, 1882.8 First, the board read its report from December 5. Then they discussed franchise realignment. The board explained its decisions to remove memberships for the Troy and Worcester clubs. The delegates for Troy and Worcester tendered their clubs’ resignations as active members, and the NL provided them with honorary membership. The NL admitted franchises from New York and Philadelphia, electing both clubs as members.9

The NL elected officers. A.G. Mills continued as president and Nick Young as secretary-treasurer. Soden, Spalding, Thompson, and Reach were elected to the Board of Directors.10

The NL considered amendments and changes to the constitution and playing rules. An important change was the introduction of the fly-ball game, by removing the foul-bound catch. The new rule increased the chance of a fair hit because a batted ball now had to be caught on the fly to generate an out. For pitching, the pitcher remained 50 feet from home base, but any delivery was permitted except the overhand throw: The pitcher could not allow the ball to pass above the line of his shoulder.11

The NL decided on important changes to its umpire corps and eliminated the related rule 64. For 1883, the NL secretary was empowered to select as umpires four men who were not connected to any club or player. Each umpire was to receive a salary of $1,000, to be received $200 per month during the five-month championship season of May-September. Umpires were to receive expenses when away from their homes. During the season, the umpires would look to the NL secretary, who was empowered to interpret the playing rules. NL clubs were required to accept any umpire assigned by the NL secretary to work a championship game. The NL addressed “kicking” — the action by players of disputing umpires’ game decisions — by solely limiting all appeals to the team captain. The NL could remove an umpire upon a request made in writing by four NL clubs. During the season, the NL secretary was empowered to fill any vacancy to the umpire corps.12

The NL moved forward to end conflict with the AA by forming a “committee of conference” comprising Mills, Soden, and Day. The committee was authorized to obtain an agreement with the AA for mutual recognition of binding contracts or other topics. The NL reinstated players named in the ineligible list.13

In other work, committees were appointed to make recommendations for the 1883 uniform14 and the 1883 championship schedule.15 John B. Sage was named the NL printer. A.G. Spalding & Brothers was provided rights for the official baseball as well as the official NL annual guide. The meeting adjourned until March.16

Concurrent with the NL annual meeting on December 6, 1882, the NWL met at Fort Wayne, Indiana, where it organized formally, adopted a constitution and bylaws, and elected officers. D.G. Morgan from Chicago was elected secretary. A telegram was received from the NL which encouraged games between their clubs and said each organization should respect the contracts of the other. The New York Clipper reported that the NWL did not commit to the requests, because it preferred the AA. Notably, like the NL, the NWL prohibited Sunday baseball games. It adjourned to the second Wednesday in January 1883.17

American Association Board of Directors Meeting, December 12, 1882

The AA board of directors met at the Grand Central Hotel in New York City on the evening of December 12, 1882. It awarded the championship pennant to Cincinnati and drafted a report to recommend membership for the Columbus, Metropolitan (New York), and new Baltimore clubs.18

American Association Annual Meeting, December 13-14, 1882

The next day, the AA convened its annual meeting, expected to last two days.19 On the 13th, the meeting went into executive session — they removed the press from the room — to discuss the AA board’s recommendation that three new clubs be admitted. The Association’s main concern was the joint ownership of the New York entrant by the Metropolitan Exhibition Company and the New York (NL) franchise. Appleton pledged that the Metropolitan club would adhere to the AA’s rules and bylaws and represent the AA interests in any action toward the NL. The rest of the delegates satisfied, the new clubs were unanimously admitted.

The executive session continued and the constitution was revised. The major changes included the relationship of the AA and its alliance clubs with other clubs and the annual dues. Any AA or AA alliance club would be subject to immediate expulsion for playing an NL or League Alliance club during 1883, or permitting any of its players to play with these clubs between April 15 and October 15, 1883 (the championship season was scheduled between May 1 and September 30, 1883). These restrictions prohibited AA clubs from loaning players out to other clubs, when those players were under binding AA contracts. The AA provided to each club an exclusive territorial right of an area of five miles radius from its home city. The privilege required foreign clubs to obtain permission from the home club to play exhibition games in this area. The AA annual dues were increased from $50 to $100. The AA enhanced the expulsion penalty to any player who signed two contracts for the same season. Finally, constitution and playing rules changes were permitted at special meetings rather than only annual meetings. The New York Clipper observed that this provision allowed the AA to end its dispute with the NL with any acceptable agreement reached between the AA and the NL.

The executive session ceased, and the meeting was opened to the press. The convention considered changes to the playing rules next. The AA adjusted the definition for a fair pitched ball, allowing any delivery not above the shoulder.20 In a break from the NL, the AA maintained the foul bound catch, and the New York Clipper commented that this lack of action reflected a preference in the AA for low-scoring games. The AA changed its umpire rules to allow for a salaried corps. Four men were to be selected to receive a salary to work as umpires, under the direction of the person appointed by the AA board. This is a notable change. Previously, clubs were responsible for the game umpire, and paid him. The AA took direct responsibility for the umpire and perfected its system for 1883, hiring professionals with AA and NL experience. Umpires were to receive at least $100 per month and traveling expenses.

During the evening, the AA elected officers. McKnight was reelected president, Pank, vice president, and Williams, secretary-treasurer. Considerable differences affected the selection of directors. Pank and Chris Von der Ahe were selected on the first ballot, while Appleton, William Barnie, and Chittenden split the support required for the other two director spots. On a subsequent ballot, Appleton and Lew Simmons were selected. The Metropolitan Exhibition Company had representation in the NL conference committee and the AA board of directors.

Four delegates from the Interstate Association appeared at the conference, and requested membership for their association in the AA alliance. Additionally, Kramer requested admittance for the Shamrock Club of Cincinnati and the Star Club from Covington, Kentucky. The AA admitted these clubs into the alliance as well.21

The question of the conference committee with the NL was introduced to the AA conference. The NL had authorized and appointed a committee to end the baseball war. Delegates for the Allegheny, Baltimore, Eclipse, and Metropolitan clubs favored a committee while the delegates for the Athletics, Cincinnati, Columbus, and St. Louis clubs opposed. Not having a majority, the conference failed to appoint a committee and adjourned until the next morning.

On December 14, the next morning, the AA convention continued. After Secretary Williams expressed a reluctance to fine AA clubs for infractions, McKnight instructed him to fine clubs when the Constitution provided for fines. The Metropolitan club was directed to employ an official scorer rather than rely upon the city reporters. McKnight returned to the matter of the conference committee, and he requested that the AA reconsider its vote from the prior day. Pank introduced a motion to reconsider the conference committee, and Sommers provided a second. After discussion, the AA delegates then voted, six in favor, and Cincinnati and St. Louis continued against. However, Kramer (Cincinnati) directed that his vote be changed to be in favor of a conference committee, and Barnie, Pank, and Simmons were appointed to confer with the NL.

The conference returned to executive session to discuss players who were blacklisted or otherwise ineligible. The St. Louis and Philadelphia clubs settled their dispute with Ed Rowen, assigning him to the Athletics. Charlie Bennett, Pud Galvin, and Ned Williamson were blacklisted for failing to sign contracts with the Allegheny club. Jerry Denny, Charles Radbourn, and Art Whitney were expelled for violating terms of their contracts with the St. Louis club. John Bergh was expelled for violating a term of contract and accepting advance money with the Allegheny club. John Troy applied for reinstatement, his case was discussed, and the AA reinstated him.

Returning to open session, the AA conference addressed other business. Secretary Williams’s salary was increased by $500. The official AA baseball was discussed. The bid from A.J. Reach was more favorable and the AA accepted its ball, linking the AA fortunes with the sporting-goods business of the NL Philadelphia owner and executive. After setting a March 12, 1883, date for a special meeting to be held at St. Louis for the purpose to consider the conference committee report, the AA conference concluded with setting the location for the next annual meeting as Pittsburgh.

In its analysis of the AA conference, the New York Clipper noted that the AA would continue to schedule championship games on Sunday, allow clubs to set their admission fees, and permit AA clubs to continue to play exhibition games during the season against other AA teams competing for the championship. This, the weekly complained, led to confusion about whether a result counted in the standings.22 These were key differences between the AA and the NL, and the means by which each organization delivered its product and controlled the business practices of clubs. NL clubs could not play baseball games on Sunday, were required to price their admission fees at a minimum of 50 cents, and offered only championship games in their home ballparks. However, the New York Clipper was quick to criticize both the NL and the AA: the NL for its acts to begin the baseball war, and the AA for its competition for players that had increased player salaries. Similarly, the paper praised the NL and AA for appointing conference committees to negotiate a compromise, with the aim of discouraging players from behaving dishonestly, breaking contracts, and getting drunk. The paper urged the AA and NL to reinstate all players except those previously expelled for dishonest play. Then, the AA and NL should agree to recognize each other’s contracts and ineligible lists to discourage players from breaking contracts and engaging in play.23

Between the NL and AA annual meetings and the Conference Committee meeting, the NWL and ISA held meetings. The NWL held its first annual meeting in Chicago on January 10, 1883. Elias Matter (Grand Rapids) was elected president and S.G. Morton of Chicago was elected secretary-treasurer. After amending its constitution, the NWL authorized Matter to meet with the NL and AA conference committees. The NWL adjourned until March 6, when it would meet in Toledo, Ohio.24 The ISA held an adjourned meeting on January 27, 1883, at Pottsville, Pennsylvania. There, the ISA limited the number of its franchises to eight from among a number of aspirants, agreed to hire four permanent umpires, and required a $65 game guarantee to visiting clubs and 50 percent of gross receipts for exhibition games.25

National League and American Association Conference Meeting, February 17, 1883, New York City

In advance of agreeing to any conference meeting, disputes between the parties to the conference continued. William H. Barnie, the manager of the AA Baltimore club, and Lew Simmons, an Athletics club owner and executive, expected the NL to release players for whom AA clubs claimed rights. However, Reach and Ferguson of the NL Philadelphia club offered contracts to two players who had signed contracts with the NWL’s Peoria club, which claimed to have an agreement with the NL to mutually recognize its contracts.26

The AA and NL agreed to meet in New York City, where A.G. Mills resided, on February 17, 1883, in a room at the Fifth Avenue Hotel. Pank, the chairman of the AA conference committee, was unable or unwilling to attend (according to Seymour and Seymour Mills, Pank refused to leave Louisville). Pank appointed O.P. Caylor, a sportswriter at Cincinnati, where he was connected with the AA club, as his proxy.27 NWL President Elias Matter was present, Mills acted as chairman of the conference, and Caylor, secretary. Initially, the AA delegates objected to the presence of Matter, because they believed the NWL was part of the League Alliance. Matter denied its connection, which the AA accepted. During a three-hour meeting, the NL, AA, and Matter settled their differences and agreed to a Tripartite Agreement.28

The New York Clipper observed that the fast compromise was possible because each association recognized each club’s player list, which effectively reinstated all players then under contract. Combined with the recognition of all contracts, the obstacle of the AA’s independence policy was surmounted. With respect to the existing disputes between clubs for rights to players, the NL effectively gave up claims on six players, the AA, nine, and the NWL, two.29

The Tripartite Agreement was designed to reduce disputes between clubs and to clarify their rights with players. All players listed by clubs party to the agreement were members in good standing until November 1, 1883, unless sooner expelled or released. No club was to contract with any listed player prior to October 10, 1883. When a club contracted with a player, it was to notify their respective association’s secretary who in turn was to notify the other two association secretaries. All valid contracts were binding and all clubs and associations were required to recognize each other’s valid contracts. Any player who signed more than one contract would be expelled. When a player was expelled by a club or association, it was expected to notify its association secretary, who was to notify the other two association secretaries. Every club and association was required to recognize each other’s ineligible list. Finally, each club received the right to reserve up to 11 players who were to earn at least $1,000 per season. By September 20, 1883, each club was required to submit its reserve list to its association secretary, who was required by October 1 to notify the other association secretaries, and then they were required to distribute the reserve lists to their member clubs by October 10. Finally, the conference agreed to establish an arbitration committee consisting of three members from the AA, NL, and NWL, for the purpose of resolving disputes involving clubs, players, and contracts, with its decisions to be final. Interestingly, Eastern papers were reported to favor this agreement, but Western papers were opposed, except for those at Cincinnati.30

National League Adjourned Annual Meeting, March 5, 1883, New York City

The NL continued its adjourned annual meeting when on March 5, 1883, noon, its clubs’ delegates arrived at the Hotel Victoria at 27th Street and Broadway in New York City.31 After the conference committee report was read, the NL unanimously adopted it and authorized A.G. Mills to ratify it. Day, Mills, and Soden were appointed as the NL members of the Arbitration Committee. The NL proceeded to other business. Philip Baker, J. Gerhardt, C.W. Jones, and Alex McKinnon were reinstated, but Herm Doescher of the Cleveland club remained expelled. At the request of some AA clubs, the NL waived its game guarantee policy to allow NL clubs to make their own arrangements for exhibition games with AA clubs. The League selected its umpire corps after adopting a rule that no umpire could come from a residence located in an NL city.32 Secretary Young was directed to interpret all disputed NL playing rules. Any player other than the club captain who disputed an umpire’s decision was to be fined $5 to $10, the funds to be paid directly into the NL treasury. During the championship season of May 1 to September 30, the NL decided to prohibit NL clubs from playing each other in exhibition games, but could arrange to play any non-NL club outside of NL cities.33

Northwestern League Special Meeting, March 6, 1883, Toledo, Ohio

The NWL met on March 6, 1883 at Toledo, where it adopted the conference committee report. It adjourned to March 14, 1883, with the season schedule and umpire selection expected to be on the agenda.34

American Association Adjourned Annual Meeting, March 12-13, 1883, St. Louis

The baseball press reported that some clubs in the AA would reject the reserve clause because it ran counter to the AA’s founding principles, and the AA would insist that the ISA receive the same privileges under the agreement as the NWL. Furthermore, any possible disputes brought to the Arbitration Committee were seen to favor the NL as the NWL had three seats.35

The AA convention continued March 12-13, 1883, when it delegates met at St. Louis.36 President McKnight convened the meeting. The AA reviewed the conference report, and the primary issue of discussion was the reserve rule. The rule would advantage some clubs, but it was stated the rule would harm older players and remove from play players who refused to work if the salary offered was too low. The Baltimore, Columbus, and St. Louis clubs were noted in opposition, but they withdrew their objections following discussion to present a unanimous acceptance of the Tripartite Agreement.37 Barnie, Caylor, and Simmons were appointed to the Arbitration Committee.

The AA turned to reinstatement of ineligible players. With an exception for Bill Craver, James Devlin, George Hall, and Al Nichols (the Louisville Four from 1877), and Dick Higham, Herm Doscher, John Bergh, and James W. Keenan of the Allegheny club, the AA reinstated all players.

The game rules were then amended. After defining a valid pitch at its annual meeting, the AA provided for the penalty. The AA changed the definition of a balk to mean any ball delivered above the shoulder. The penalty for a balk was to give the batter and runners a base.38 As in the NL, the umpire was made the sole arbiter of all plays, allowing only the captain to dispute his game decisions.39 Any fine imposed by the umpire was the obligation of the club and due within 10 days to be paid to the AA secretary. The club could withhold the fine from the player’s salary. The penalty for unpaid fines was to expel the offending club. The AA retained the $65-per-game guarantee when the home club retained the gate receipts except on “Decoration-day, Fourth-of-July, and State holidays,” when the visiting club was allocated 12.5 cents for every entrant.40 The AA extended its exclusive-territory privilege to AA alliance members, permitting a single AA alliance member per city.41

Like the NL, the AA developed and amended its umpire policies and rules. Secretary Williams was to select four men as umpires to earn $140 a month and two assistants to earn $10 per game.42 In addition, umpires were to be reimbursed travel expenses up to $3 per day. Umpires were not permitted to travel or lodge in the same hotel with a visiting AA club. Umpires were not permitted to borrow money from players under contract or club officers, directors, or stockholders. To defray the cost of the umpire corps, AA clubs were assessed $125 per month. Umpires could be removed from their position by the AA secretary, upon written appeal by at least five AA clubs, or when two clubs certify that an umpire appeared on the field in a state of intoxication. Finally, the home club was directly liable to maintain order and protect the umpire during championship games under penalty of forfeiture of the game. The umpire was responsible for determining when to direct the home club to maintain order.43 Williams had accepted 30 applications for the umpire positions and appointed four men and two alternates.44

With the AA acceptance, the Tripartite Agreement became baseball law, one that provided an institutional framework for relations among competing associations, rather than the constitutions and bylaws that governed member clubs, or the rules of the old National Association that focused on players and their clubs. It was and is a significant business-of-baseball document. The key parts relate to the mutual recognition of contracts, the player reserve, and the Arbitration Committee. The Arbitration Committee did not resolve disputes during 1882-1883 and there existed uncertain acceptance of the player reserve outside of the NL. However, the mutual recognition of contracts was attractive to other professional associations and clubs. Harold Seymour and Dorothy Seymour Mills provide plenty of evidence of NL clubs obtaining players by ignoring their contracts with independent clubs.45 Clubs or associations seeking the protection of mutual recognition of player contracts by joining an alliance with a Tripartite Agreement signatory was a credible beginning to organizing professional baseball beyond its highest level.

Northwestern League Meeting, March 14, 1883, Toledo, Ohio

The NWL held its adjourned meeting on March 14, 1883 at Toledo. The NWL increased its annual dues from $50 to $100 and adopted the NL’s playing rules, except that it maintained the old plan of a list of men who were permitted to umpire a game. In response to the Toledo club contracting with Fleetwood Walker, an African-American, the Peoria Club presented a motion that no NWL club be permitted to “employ a colored player.” After discussion, the Peoria delegate withdrew his motion. Two clubs were admitted to its alliance: Port Huron and Indianapolis.46

Interstate Association Meeting, March 31, 1883, Wilmington, Delaware

The ISA met on March 31, 1883, at Wilmington, Delaware. It admitted Brooklyn and Trenton, increasing the number of franchises to eight.47

American Association Special Meeting, Board of Directors, June 4, 1883, Columbus, Ohio

The AA called a special meeting of its Board of Directors for June 4, 1883, at Columbus.48 The purpose of the meeting was to resolve a dispute of games played under protest by the Allegheny club with the Athletic club. George Washington Bradley appeared with the Athletics in games against Allegheny on May 21 and 22. The games were won by the Athletics, and Allegheny sought wins for both. Bradley had been released by the Cleveland club, and the Alleghenys’ McKnight alleged that AA Secretary Williams had not been notified by game time of the release, violating section 7 of article VI. The Athletics’ Simmons observed that under section 3 of article VII, the Athletics could play Bradley for five games to fill a vacancy.49

Meeting at Cincinnati rather than Columbus, the directors concluded that although the Athletic club technically violated one article of the constitution, Bradley was eligible under another article. Therefore, the directors decided the games in favor of the Athletic club and proposed an amendment to the AA constitution to prevent a repeat of a similar protest.50

American Association Special Meeting, September 1, 1883, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

The AA called a special meeting on September 1 at Pittsburgh.51 The primary purpose of the meeting was to achieve a consensus for the reserve rule. After considerable discussion, the AA unanimously accepted the 11-man reserve rule, however with limitation. The players of the Providence club were rumored to be moved to Philadelphia. The delegates decided that in the event a franchise was transferred between locations, the agreements regarding the reserve rule were “null and void.” The Philadelphia club’s rights to the players with Providence contracts would not be recognized by the AA.52 The AA likely had in mind the transfer of the Troy and Worcester NL franchises to New York and Philadelphia after the 1882 season. Some of those players became stars in their new clubs.

Secretary Williams had been assigning game dates to the men in the umpire corps. However, at the request of some clubs after the announcement of the schedule, Williams had changed some of the assignments. The AA directed Williams to cease making the changes.53

Another issue for AA clubs was the behavior of the Metropolitan club and the Metropolitan Exhibition Company, which also controlled the NL New York club. Secretary Williams was directed to inform the Metropolitan club that it would be expelled if the AA determined that the Mets were connected to the organization of a club at Hartford, Connecticut, as rumored. Furthermore, the AA directed Williams to inform the Mets that going forward, they had to fulfill two conditions to maintain their AA membership. The first was separate and distinct management. The second required the Mets to maintain their own grounds.54

The AA received applications for admission from clubs in Brooklyn, Chicago, Hartford, and Indianapolis. McKnight deferred discussion on expansion to the December annual meeting.55

If the reserve rule was to be part of Organized Baseball, then the AA clubs must have thought about other associations’ rights. Under the AA Constitution, AA clubs recognized its Alliance clubs’ contracts, but the Constitution offered no provision for any privileges by a reserved-player list. At the end of the 1882 season, Cincinnati signed several Indianapolis players to 1883 contracts without compensation to the Indianapolis club, which wished to retain these players. The New York Clipper believed that this action demonstrated that AA clubs would not protect their alliance members. It cited Secretary Williams’s statement that the AA believed alliance clubs were not beneficial for its clubs. Williams also noted that ISA clubs in particular had no player reserve privileges, as the ISA organized after the Tripartite Agreement. However, under the fifth clause of the Tripartite Agreement, the writer believed it extended reserve rights to AA alliance clubs, including those in the ISA. The writer noted that the AA organized to protect its members from NL clubs and expected new associations to similarly form in opposition if the NL and AA failed to admit new associations to their mutual agreements.56

Union Association Organizational Meeting, September 12, 1883, Pittsburgh, and Union Association Special Meeting, October 20, 1883, Philadelphia

Barney Terrell covers the Union Association (UA) meetings in his articles on the subject, so this discussion is to place into context the anticipated impact due to the organization of the UA.57 By the time of the Arbitration Committee meeting (see below), the UA had organized an association with six clubs in large cities, including some that overlapped with the NL and AA, including Baltimore, Chicago, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis. Washington, home to NL President Nick Young, also had a franchise. The UA also planned franchises for Brooklyn and Indianapolis if they were not offered admission to the AA.58 One of its fundamental principles was to refuse to recognize the rights clubs derived from the reserve rule which had been negotiated by the parties to the Tripartite Agreement. The UA recognized all valid contracts between players and outside clubs, and sought mutual recognition for its contracts with players. To protect itself, the UA threatened any baseball association that failed to recognize its contracts with players: “[A]ny attempt on the part of any baseball organization to induce players who have signed contracts with this Association to violate said contracts must be considered as a declaration of war, and will be met by all the means at our command.”59 In its analysis of the UA entry and its principles, the writer for the New York Clipper speculated that the true purpose of this action would be a trade war which would either result in a combination with the incumbents or would cause their failure. The writer also expressed concern about differences in official playing rules between the major associations. It preferred uniformity of playing rules rather than market confusion from structure and competition.60

Perhaps a response to this threat was the formation of several reserve clubs, such as reported at Boston and Cincinnati. These were effectively auxiliary teams of the NL and AA clubs. Their purpose was twofold. One was to reduce the amount of talent to prospective entrants. Another was to offer home customers baseball games on offdays or when the home club was on the road. These games would keep the home grounds in use.

Interstate Association Special Meeting, September 21, 1883

At the ISA’s special meeting on September 21, at Philadelphia, the ISA resolved that the lack of reserve privileges for its clubs was “an outrage and gross injustice.” The ISA noted that alliance clubs were promised the benefits and protections for their player contracts from the Tripartite Agreement.61

Union League Organizational Meeting, September 25, 1883, New York City

The Union League (UL) organized on September 25, at the Earle Hotel in New York City. The location of franchises was sought directly along rail lines between Boston and Richmond, Virginia. After election of officers and a board of directors, clubs were admitted to membership. The playing rules of the AA were adopted, and the Shibe ball was selected for the official baseball.62 Importantly, the UL resolved to recognize the reserve rule of the NL and AA.63 Interestingly, the UL admitting franchises at Boston, Brooklyn, and Philadelphia potentially ran afoul of the AA and NL clubs’ franchise rights to exclusive territories. The UL instructed the board to send a representative to the annual meetings of the NL and AA. Their meeting adjourned to January 3, 1884, when the UL would meet at the Bingham House in Philadelphia.64

Arbitration Committee Meeting, October 27-28, 1883, New York City

In effect, the meeting of the Arbitration Committee closed the 1883 season. It held its meeting over October 27-28 in the Fifth Avenue Hotel. Day, Mills, and Soden were present for the NL, Barnie, Caylor, and Simmons for the AA, and Matter for the NWL. Mills was selected chairman of the meeting, and Caylor, secretary.65 The objective of this meeting was to develop an agreement to be adopted by baseball associations at their 1883 annual meetings.

The committee noted that the baseball season was a success. Most clubs were thought to have earned profits. No club subject to the Tripartite Agreement brought any dispute to the Arbitration Committee. No dishonest play or act was detected. No breach of contract was reported.66

After a lengthy discussion, the committee endorsed the reserve rule. It noted that any player who was reserved remained reserved by the association in which the player contracted through the connection of his club. As a result, reserved players could not negotiate terms with outside clubs.67 This interpretation broadened the meaning of the reserve, extending it from a club privilege to an association privilege. The Arbitration Committee stated that the reserve rule restrained clubs, rather than players. Clubs were prevented from competing for players, and raising salaries to such levels that only a few clubs in the largest cities would offer professional baseball. The reserve rule, the Arbitration Committee was convinced, increased employment for baseball players, for without it, “the great majority of baseball-players would soon be without occupation.”68

The key outcome of the meeting was the National Agreement, a document recommended for adoption by the AA and NL at their annual meetings. The document built upon the Tripartite Agreement and was the basis for Organized Baseball. The document was specific to the 1884 season, but was intended to be updated for future seasons. As such, the document was intended to be a living institutional framework. The agreement consisted of 11 parts.

First, association secretaries were to notify the other associations subject to the agreement of any player made ineligible by a member club or the association. Similar notice was to be provided for those players whose ineligibility was removed.69

Second, the 1884 contract length was seven months, April 1, 1884-October 31. Clubs were permitted to begin to offer players contracts for the following season on October 10, with no prior negotiations permitted between clubs and players or their agents.70

The third section covered the reserve rule. Clubs were permitted to submit by September 25 up to 11 names of players who were then under contract for the purpose of reserving them for the following season. The reserving club was obligated to pay a minimum salary of $1,000 if either in AA or NL, or $750 if a member of NWL. The secretary of each association was to distribute their list of reserved players to the secretaries of other associations by October 5. The reservation was effective until either the player signed a contract or the club released the player from reservation.71

Fourth, all contracts made in accordance of the National Agreement were to be valid and binding between the club and the player. Unless the player was reserved, no other club was permitted to negotiate for his services for the ensuing season prior to October 10.72 The fifth section regulated releases. It directed that clubs that released, reserved, or contracted players were required to notify their association’s secretary, who was then to notify in writing other associations’ secretaries providing the reason for the release. Association secretaries were to provide similar notification of clubs that disbanded or were expelled. Any of these players subject to the fifth section were ineligible to contract for 10 days after the mailing of the written notice.73 The sixth section prohibited managers and umpires from providing services to more than one association while under contract.74

The next two sections protected a club’s right to an exclusive territory. Section seven institutionalized rights to an exclusive territory by limiting admission to the National Agreement by clubs from places where no club member subject to the National Agreement was located on October 10, 1883.75 Under section eight, clubs could neither play games in which an ineligible player appeared nor play games against clubs that played in games during which an ineligible player appeared.76

The final sections provided the judicial framework. The Arbitration Committee was to consist of three members from each association subject to the National Agreement to be appointed prior to March 31 of each year and to serve until the following March 31. Its decisions were to be final and binding. The Arbitration Committee was empowered to impose the penalty of forfeiture of any rights or privileges granted by the National Agreement on any party subject to the National Agreement.77

The Arbitration Committee demonstrated remarkable progressivism, inviting into an alliance of all professional associations and clubs “organized upon the basis of honest play and financial responsibility.”78 However, there was a caveat. Clubs located in occupied territory, one containing an existing club subject to the Tripartite Agreement, were not welcome, and clubs subject to the agreement should exclude these outside clubs.79 Therefore, the Arbitration Committee advocated exclusive territories for franchises in Organized Baseball. In effect, many of the clubs in the newly organized associations would be viewed as outside clubs.

Most importantly, the 1883-1884 National Agreement would institutionalize the 1882-1883 Tripartite Agreement. The NL and AA both demonstrated little use for an alliance with clubs or other professional associations.80 The National Agreement between professional associations would prove useful to reducing disputes through the orderly process of mutual recognition of contracts, generally recognizing — if not accepting — rights to reserve players and the authority of the Arbitration Committee, and the enforcement of rights and privileges through newly recognized exclusive territories.

Conclusion

The 1883 season was a grand success due to the harmony wrought by the 1882 business meetings. The exciting pennant races in each of the member associations, lack of disputes requiring the attention of the Arbitration Committee, and financial success of many clubs reflected the nationwide baseball boom. The success of the season led the Arbitration Committee to recommend that member associations endorse the National Agreement of Professional Baseball Clubs — an amended Tripartite Agreement — which sought to bring more professional associations into Organized Baseball’s orbit, continue the reserve rule, and reinforce the exclusive franchise rights of clubs in member associations. The importance of this institutional framework is established by its entrenchment of the reserve clause well into the twentieth century, and the exclusive franchise territories which continue to the present day.

Notes

1 During 1882, the AA clubs were located in larger cities, priced their admission at 25 cents, and were known for Sunday baseball and offering alcohol in their parks. The NL clubs occupied a number of smaller locations, collected a 50-cent fee, played no games on Sundays, and offered no liquors to their customers. See the 1882 chapter.

2 The AA’s independence policy, also known as the nonintercourse policy, was a result of the NL recognizing contracts signed between players and its clubs after the players had signed contracts with AA clubs. For example, Detroit (NL) signed Dasher Troy after he signed a contract with the Philadelphia Athletics (AA). Similarly, Sam Wise signed a contract with the League’s Boston club after he signed one with the Association’s Cincinnati franchise. The policy prohibited games between NL and AA clubs during the championship season. During the season, NL rules prohibited its clubs from scheduling exhibition games on their home grounds while AA clubs could and did schedule exhibition games on their home grounds. The policies removed a source of revenue for NL clubs, particularly those from the East who were traveling in the West and could not obtain games at Cincinnati or St. Louis, where the crowds were immense. “The Coming Conventions,” New York Clipper, December 2, 1882: 597. Due to the uncertainty over the policy, which required the AA to expel member clubs for playing interleague games, few games between NL and AA clubs were scheduled after the close of the 1882 championship season. Cincinnati was an exception. The club released its players, a technicality, and games were scheduled with several NL clubs. After the AA pennant-winning Cincinnati Red Stockings split a pair of home games with the NL pennant-winning Chicago White Stockings, the AA notified Cincinnati that it would be expelled if it played games with the NL clubs from Cleveland and Providence. See New York Clipper, October 7, 1882: 467. Following the championship season, the player poaching continued. The Pittsburgh Alleghenys “expelled” Charlie Bennett, Ned Williamson, and Pud Galvin, all of whom signed contracts to play in Pittsburgh in 1883, making them ineligible to play in the AA. New York Clipper, December 16, 1882: 626. Instead, they each signed contracts with their 1882 NL employers, Detroit, Chicago, and Buffalo, respectively. The Alleghenys filed suit against Bennett to restrain him from playing for any other club during 1883, but the judge held for Bennett on the matter of performance and dismissed the suit. New York Clipper, November 25, 1882: 583. In the other direction, Pat Deasley signed contracts with Boston — to obtain salary payments owed for 1881 and 1882 — and St. Louis — twice! — from which he received more advance money. New York Clipper, December 2, 1882: 594. See also “Deasley vs. The Boston Club,” New York Clipper, December 9, 1882: 616. The New York Clipper noted that as late as November 1882, NL clubs continued to attempt to contract with players who had signed 1883 contracts with AA clubs. December 2, 1882: 597.

3 The interest was so great for the Grand Rapids team, the stock subscription was increased from $2,000 to $4,000. New York Clipper, August 12, 1882: 335; August 26, 1882: 363.

4 Delegates were received from Peoria (Illinois), Bay City (Michigan), Springfield (Illinois), East Saginaw (Michigan), Toledo, Fort Wayne (Indiana), and Quincy [Illinois]. Grand Rapids did not send a representative. At its earlier organization meeting, Elias Matter was elected president, V.H. Dumbeck, vice president, with Dumbeck, E.T. Bennett, J.E. Seery, John Rush Matter, W.T. Colbern, Max Nirdlinger, and Charles Overrocker, directors. New York Clipper, November 4, 1882: 531, 536; “The Northwestern League,” New York Clipper, December 16, 1882: 629.

5 Eli Fox was elected temporary chairman and A.F. Richter elected secretary. The clubs admitted in the association were Active of Reading, Harrisburg, Anthracite (Pottsville, Pennsylvania), Burlington, Trenton, Merritt (Camden, New Jersey), and Quickstep (Wilmington, Delaware). New York Clipper, November 18, 1882: 562.

6 Delegates included Fox for Active; Richter, Merritt; Waitt, Quickstep; Henry Myers, Harrisburg, and, Fielders, Anthracite. The officers elected were: Fox, president, Fielders, vice president, Richter, secretary and treasurer. The elected directors were Fox, Fielders, Waitt, Myers, and Richter. New York Clipper, December 2, 1882: 594.

7 “The League Convention,” New York Clipper, December 16, 1882: 629. Cleveland suspended Doscher for “insubordination and dishonorable conduct.” New York Clipper, November 25, 1882: 583. Doscher’s given name was John Henry Doscher.

8 Delegates included Soden and A.J. Chase, Boston; John. B. Sage and Hughson, Buffalo; A.G. Mills and A.G. Spalding, Chicago; C.H. Bulkeley and George W. Howe, Cleveland; Thompson, Detroit; H.B. Winship and Harry Wright, Providence; A.J. Reach, Philadelphia; John B. Day, New York; Hotchkiss, Troy, and Brown, Worcester.

9 New York Clipper, December 16, 1882: 629.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid. Players were reinstated, including Lipman Pike, E.J. Caskins, Mike J. Dorgan, Edward Nolan, Bill Crowley, E.M. Gross, Lew J. Brown, L.P. “Buttercup” Dickerson, Sadie P. Houck, and J.J. Fox. In other cases, NL clubs would not be penalized for playing games with clubs which included Philip Baker, Charles Jones, or Joe Gerhardt. For a history of the ineligible and blacklist, see John Thorn, “Baseball’s Bans and Blacklists,” ourgame.mlbblogs.com.

14 Bulkeley, Day, and Wright. New York Clipper, December 16, 1882: 629.

15 Spalding and Soden. New York Clipper, December 16, 1882: 629.

16 New York Clipper, December 16, 1882: 629.

17 “The Northwestern League,” New York Clipper, December 16, 1882: 629.

18 J.H. Pank (Louisville Eclipse), Lew Simmons (Philadelphia Athletics), and Christopher Von der Ahe (St. Louis Browns) were present. Justus Thorner (Cincinnati) was absent. “The American Association Convention, New York Clipper, December 23, 1882: 645.

19 The delegates recorded present were: H.D. McKnight (Allegheny), Simmons and William Sharsig (Athletics), A.P. Houck and William Barnie (Baltimore), Louis Kramer (Cincinnati), H.J. Chittenden and Horace Phillips (Columbus), Pank, Walter Appleton and James Mutrie (Metropolitan), and Von Der Ahe and D.L. Reid (St. Louis). Ibid.

20 “A fair ball is a ball delivered by the pitcher while standing wholly within the lines of his position, and while facing the batsman; and his hand, while in the act of delivery, must pass his side below the line of his shoulder, and the ball when thus delivered must pass over the home base and the height called for by the batsman.” Ibid.

21 “The American Association Convention,” New York Clipper, December 23, 1882: 645.The Inter-State Association held a meeting December 16, 1882, in the Athletic Club rooms in Philadelphia, to receive the report of their accepted membership in the AA alliance and that their contracts would be recognized by AA clubs. New York Clipper, December 23, 1882: 647.

22 “The American Association Convention,” New York Clipper, December 23, 1882: 645.

23 “The Work of the Conventions,” New York Clipper, December 30, 1882: 661. It recommended the NL make the first move by releasing claims to contested players. “The Conference Committees,” New York Clipper, January 13, 1883: 695.

24 New York Clipper, January 20, 1883: 709.

25 New York Clipper, February 3, 1883: 739. The game guarantee reflected the AA’s business policy for its clubs to capture the benefits from developing their home market.

26 New York Clipper, January 20, 1883: 711. Reach alleged A.C. Anson had acted as an agent for the Philadelphia club in offering the contracts to Frank Ringo and John Coleman, who had signed their contracts in late October 1882, prior to the NL’s agreement with the NWL. See “Coleman and Ringo,” New York Clipper, January 27, 1883: 728. Ringo claimed he and Coleman had signed contracts dated August 22, 1882 before the existence of the NWL. New York Clipper, February 24, 1883: 789. Anson was also involved in a conflict with the AA’s St. Louis club concerning Hugh Nicol, who had signed a personal contract — not an NL contract — to play baseball for Anson. When Nicol learned that he would not be an everyday player for Chicago, he desired another club. Anson wanted $100 for Nicol’s release, but St. Louis offered $50. “The Chicago Club and Nicol,” New York Clipper, January 6, 1883: 674.

27 “The Conference Meeting,” New York Clipper, February 17, 1883: 775. Seymour and Seymour Mills record the effort Mills expended to achieve the meeting. They state that Pank refused to attend the meeting and Mills asked for a proxy. They also state the meeting was held at the Victoria Hotel in New York City. Harold Seymour and Dorothy Seymour Mills, Baseball: The Early Years (New York. Oxford University Press, 1960), 144-145.

28 “The Work of the Conference,” New York Clipper, February 24, 1883: 790. Nemec provides the length of the meeting at 5½ hours. David Nemec, The Beer and Whiskey League (Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press, 1994), 45.

29 “The Work of the Conference,” New York Clipper, February 24, 1883: 790. The New York Clipper recorded the resolutions as follows. New York released John Reilly to Cincinnati. Cincinnati released claims to Buck Ewing, Mickey Welch, and Patrick Gillespie. Boston released Pat Deasley to St. Louis (who relinquished Radbourn, Denny, and Whitney) and Buttercup Dickerson to Allegheny. Allegheny released Ned Williamson, Charlie Bennett, and Pud Galvin. Providence reinstated Philip Baker. Detroit reinstated Joe Gerhardt. Boston reinstated Charley Jones. The NWL released Ringo and Coleman to Philadelphia. The New York Clipper endorsed the Arbitration Committee as a sort of baseball senate, a means by which to govern professional baseball, but it opposed the continuation of the reservation rule. Seymour and Seymour Mills record an unnamed 18 players who had signed two or more contracts. They state that resolution was achieved by “arbitrary [assignment] to specific clubs by mutual agreement.” Baseball: The Early Years, 146.

30 “The Work of the Conference,” New York Clipper, February 24, 1883: 790.

31 The delegates included Soden, Chase, Hughson, Spalding, Howe, Thompson, Day, Reach, J.J. Rogers (Philadelphia), and Wright. “The League Convention,” New York Clipper, March 10, 1883: 818. The location of the meeting is noted in Seymour and Seymour Mills, 145.

32 A.F. Odlin of Lancaster, New Hampshire; S.M. Decker, Bradford, Pennsylvania; W.E. Furlong, Kansas City, Missouri, and, Frank Lane, Norwalk, Ohio. “The League Convention,” New York Clipper, March 10, 1883: 818.

33 “The League Convention,” New York Clipper, March 10, 1883: 808, 818.

34 New York Clipper, March 17, 1883: 840.

35 New York Clipper, March 3, 1883: 803. “The American Association Meeting,” New York Clipper, March 17, 1883: 839.

36 The delegates included McKnight, Simmons, Sharsig, Barnie, Caylor, A.S. Stern(Cincinnati), Phillips, Pank, Mutrie, Von der Ahe, J.P. Sullivan (St. Louis). “The American Association Meeting,” New York Clipper, March 17, 1883: 839.

37 Ibid.

38 The AA modified this penalty further at its umpire meeting on March 18, 1883, at Columbus, Ohio. Secretary Williams required the umpire to enforce “invariably” maintaining the hand below the pitcher’s shoulder, but to warn the pitcher on each batter before ruling for a balk. “The Official Umpires,” New York Clipper, April 28, 1883: 83.

39 “The American Association Meeting,” New York Clipper, March 17, 1883: 839.

40 The visiting club to receive whichever amount was greater, either the guarantee or the gate share. The number of entrants was adjusted for the number of players, umpire, policemen, club officers, and members of the press. “The American Association Meeting,” New York Clipper, March 24, 1883: 5.

41 Ibid. This privilege would be a source of conflict in New York and Philadelphia during the 1883 season. For instance, after the Philadelphia club refused to permit NL clubs from arranging exhibitions with the Athletic club, the Athletic club objected to arrangements for games at Philadelphia between the Merritt Club of Camden, New Jersey, and the Philadelphia club. In response, the Merritt club threatened to leave the ISA, part of the AA alliance. New York Clipper, April 7, 1883: 35. Such behavior went in the other direction, too. Cleveland refused to schedule the Metropolitans in October because the Mets refused to permit Cleveland to play in Brooklyn during the championship season. New York Clipper, September 29, 1883: 454.

42 “The American Association Meeting,” New York Clipper, March 17, 1883: 839.

43 “The American Association Meeting,” New York Clipper, March 24, 1883: 5.

44 The men appointed as AA umpires were John Kelly of New York; William H. Becannon, New York; Charles F. Daniels, Hartford, Connecticut; and Benjamin Sommer, Covington, Kentucky. John E. Bass of Brooklyn, New York, and J.J. Magner of St. Louis were appointed alternates. Ibid.

45 Baseball: The Early Years, 97.

46 “The Northwestern League,” New York Clipper, March 24, 1883: 7.

47 “The Interstate Association,” New York Clipper, April 7, 1883: 35.

48 “The Matter of Contracts,” New York Clipper, June 2, 1883: 171.

49 Ibid.; “Bradley Decided Eligible,” New York Clipper, June 9, 1883: 187.

50 ”Bradley Decided Eligible.”

51 The delegates present were McKnight, Simmons, Barnie, Houck, Stern, Caylor, Gundersheimer (Columbus), Sullivan, and Williams. No delegates were present from Eclipse, Metropolitan, and St. Louis clubs. “The American Association Meeting,” New York Clipper, September 8, 1883: 401.

52 “The American Association Meeting,” New York Clipper, September 8, 1883: 401.

53 Ibid.

54 Ibid. The St. Louis correspondent of the New York Times was reported to have an interview with the Mets’ Appleton. Appleton was unhappy about Williams’ instructions and the AA’s treatment of the Mets. Appleton stated that if the Mets could not locate separate grounds for 1884 they would withdraw rather than be expelled. Appleton claimed that the Mets made less money as members of the AA during 1883 than when they were League Alliance members in 1882. Furthermore, the New York Clipper reported that Mutrie acknowledged that most players playing for Hartford were signed to contracts with the Mets. “The Metropolitan Club,” New York Clipper, September 29, 1883: 455. However, New York Clipper noted that two New York club (NL) players played for Hartford. See September 29, 1883: 453.

55 “The American Association Meeting,” New York Clipper, September 8, 1883: 401.

56 “New Professional Associations,” New York Clipper, September 22, 1883: 440.

57 Barney Terrell, “The 1883-84 Winter Meetings of the Union Association,” elsewhere in this book.

58 “The Union Baseball Association,” New York Clipper, September 22, 1883: 435. “The Union Association,” New York Clipper, October 27, 1883: 523.

59 “The Union Association,” New York Clipper, October 27, 1883: 523.

60 “Competitive Baseball Associations,” New York Clipper, September 8, 1883: 399.

61 New York Clipper, September 29, 1883: 453.

62 The delegates included two clubs from Richmond, three from Baltimore, and others from Trenton, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, Hartford, and Boston. Sidney E. Clarke of Hartford was elected president; L. Moxley, Washington, D.C., vice president; and Francis C. Richter, Philadelphia, secretary. The directors elected included Felix J. Moses of Richmond; H.H. Diddlebock, Philadelphia; William Dooley, Brooklyn; and W.S. Miller, Reading, Pennsylvania. Four clubs were admitted: Virginia Club of Richmond, Keystone Club of Philadelphia, Atlantic Club of Brooklyn, and the Hartford Club of Hartford, Connecticut. A Boston club was to be organized and admitted later. An important exception to the AA rules was the adoption of the fly-ball game. “The Union League,” New York Clipper, October 6, 1883: 469.

63 Ibid.

64 Ibid.

65 Nemec, 55.

66 “The National Agreement,” New York Clipper, November 10, 1883: 556.

67 “Meeting of the Arbitration Committee,” New York Clipper, November 3, 1883: 543.

68 “The National Agreement,” New York Clipper, November 10, 1883: 556.

69 “The National Agreement of Professional Baseball Associations,” New York Clipper, November 10, 1883: 557.

70 Ibid.

71 Ibid.

72 Ibid.

73 Ibid.

74 Ibid.

75 Seymour and Seymour Mills noted that this section was a response to the organization of the UA, which was backed by monied investors. Baseball: The Early Years, 151.

76 “The National Agreement of Professional Baseball Associations,” New York Clipper, November 10, 1883: 557.

77 Ibid.

78 “The National Agreement,” New York Clipper, November 10, 1883: 556.

79 Ibid.

80 Baseball: The Early Years, 103.