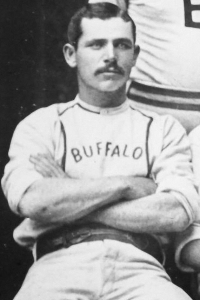

Bill Crowley

According to his obituary in 1891, Bill Crowley was “at one time, one of the best ball players that donned a uniform.”1 A 5-foot-7, 159-pound right-handed outfielder, Crowley often played bigger than his size, and was considered one of the heaviest and hardest hitters of his time.2 Crowley was known primarily for his defensive prowess, especially his arm. Crowley recorded four outfield assists on May 24, 1880, and repeated the feat three months later, eventually tallying 23 on the season.

According to his obituary in 1891, Bill Crowley was “at one time, one of the best ball players that donned a uniform.”1 A 5-foot-7, 159-pound right-handed outfielder, Crowley often played bigger than his size, and was considered one of the heaviest and hardest hitters of his time.2 Crowley was known primarily for his defensive prowess, especially his arm. Crowley recorded four outfield assists on May 24, 1880, and repeated the feat three months later, eventually tallying 23 on the season.

Crowley’s career was marked by inconsistency, owing in large part to troubles with his throwing arm and his alcoholism, which got him banned from the National League in 1881, and kicked off a minor-league club in Toledo later in the decade. When Crowley was at his best, though, precious few outfielders could combine his fielding ability with his strong and accurate throwing arm. His peak lasted from 1879 to 1884, primarily playing with the National League’s Buffalo and Boston clubs. Modern metrics suggest that he was 11 percent better than the average hitter in his leagues during this span (via OPS+), which when coupled with his proficient defense, made him one of his era’s most well-rounded ballplayers. His only league championship came with the 1883 Philadelphia Athletics, but Crowley was released in the thick of the pennant race and thus could not celebrate with his hometown team.

William Michael Crowley was born in Philadelphia on April 8, 1857. The son of Irish immigrants, he worked in a print factory in his hometown of Gloucester, New Jersey, and in a mill in Washington, New Jersey, before signing with the National Association’s Philadelphia White Stockings in 1875. Census records of the time do not give the identity of Crowley’s father, but his mother, Mary, worked as a housekeeper. His older brother, Francis, and his younger brother, Joseph, also worked in the print factory. His sister, Sarah, worked in the cotton mill. Eight days shy of his 18th birthday, The Times of Philadelphia described Crowley as of “fine physique” and “remarkable judgment.”3 Crowley, 18 years old, was the Association’s youngest player, and served primarily in a utility role, splitting time between third base and center field. He struggled at the plate, batting .081 (3-for-37) in his rookie campaign, but was praised for his “fine catches” in center field.4 His third-base defense was considered weak,5 and Crowley shifted permanently to the outfield for the majority of his career.

After missing the 1876 season, Crowley was signed by the Louisville Grays of the National League for the 1877 campaign. That season he had his first brush with the less than savory elements of the game: Four of his teammates – shortstop Bill Craver, left fielder George Hall, third baseman Al Nichols, and star pitcher Jim Devlin – were banned from baseball after the season for throwing games. The 20-year-old Crowley acquitted himself well in Louisville, batting .282 in a league-leading 61 games played.

Crowley slipped out of the major leagues after 1877, and linked up with Buffalo of the International Association in 1878. He played a handful of games behind the plate, forming a battery with baseball’s first 300-game winner, Pud Galvin.6 More often, though, Crowley played in the outfield and continued to establish himself as a reliable hitter. Buffalo joined the National League in 1879, and Crowley settled into an everyday right-field role. His steady play during his two years with the Bisons was quite the change of pace for the Buffalo club, which had a 46-32 record in 1879 but slipped to 24-58 in 1880. Despite the poor showing from his club, Crowley again was an above-average hitter, and his 23 outfield assists ranked fourth in the league.

In Buffalo Crowley met one of his lifelong best friends, third baseman Hardy Richardson. Richardson became one of the game’s early superstars, batting over .300 seven times and leading his league in home runs twice.

As 1880 drew to a close, Crowley received a $1,000 offer from the Boston Red Stockings, and jumped at the chance to play for future Hall of Famer Harry Wright, who carried six pennants to his name as the skipper of both the National Association and National League’s Boston clubs.7 Unfortunately for Crowley and Boston, the 1881 team fared poorly, and weathered three separate six-plus-game losing streaks. Crowley’s offense took a bit of a downturn; he batted .254 with eight fewer extra-base hits than the year prior.

The 1881 season was pivotal in Crowley’s career, and not to his benefit. He was banned from the National League for what was labeled “general dissipation and insubordination” by League President William Hulbert. In all, Crowley and eight others, including Lip Pike, were barred, likely due to drunkenness and suspected game fixing.8 The newly formed American Association respected the ban; Crowley lost an appeal in March and did not play in professional baseball in 1882.9

The ban was lifted in 1883 and Crowley signed with his hometown American Association team, the Philadelphia Athletic Club. Philadelphia sportswriters were protective of their favorite son, declaring that his blacklisting was for “no known cause.”10 Crowley’s first appearance with his new team came on April 7, when he helped the team christen its new grounds at Twenty-Sixth and Jefferson Streets in an exhibition game against Yale. Crowley wasted no time making an impression, rapping a pair of doubles from the number-three position in the lineup, and making a spectacular catch, complete with a pair of somersaults.11

This would be one of few bright spots for Crowley in the early part of 1883; he was hitless his other four games in April, ending the month with an .087 batting average (2-for-23).12 Crowley’s performance reached a low point on April 25, when he went 0-for-5 against a minor-league nine from Camden, New Jersey, that folded by July.13

May treated the 26-year-old a bit better, as he batted .279 with several clutch hits and turned in stellar fielding. However, as the month drew to a close, Crowley had a rare lapse in fielding proficiency when he muffed a key fly ball in a May 30 tangle with Cincinnati, leading to the Reds taking the victory in extra innings in front of a “howling mass of humanity.”14 This game was dubbed “one of the greatest struggles for supremacy that has ever taken place on the ball field,” and was played before an estimated 15,000 fans, so many, in fact, that they could not help but interfere with several foul balls.15

The spotlight would continue to betray Crowley in 1883, when the surehanded outfielder made four errors in front of 12,000 fans during a July 1 tilt with the St. Louis Browns.16 Crowley played infrequently during the summer, with young catcher Jack O’Brien and backup outfielder Bob Blakiston getting playing time in center field.17

A couple of days into September, Crowley was no longer a member of the Athletics, having been released while the team was in the thick of a pennant race. The Athletics must have had its issues with Crowley, as they decided that they would rather have center field patrolled by out-of-position players or weak bench options, all while tied with the Browns. It appeared that the club made the correct call: The Athletics rattled off eight wins in their next nine contests, including a series victory over the impressive Browns. But the Athletics wound up winning the American Association crown.

Crowley soon found another home, playing the remainder of the 1883 season with the Cleveland Blues of the National League. There he found his stride quickly, notching seven hits in his first three games.18 Crowley was likely aided by batting sixth in the lineup, with stars Fred Dunlap and Jack Glasscock helping to take the pressure off the beleaguered outfielder.19 While his bat was lively, his once powerful arm began feeling the brunt of long throws from center field (ballparks of the day typically exceeded 450 feet in dead center), and he was pulled from a September 20 game.20

In October the Beaneaters once again came calling, having apparently forgiven Crowley for his past indiscretions and offering him an $1,800 contract, which Crowley spurned.21 A month later the Beaneaters upped the offer to $1,900 and Crowley was Boston-bound.22 The Times-Democrat in New Orleans reported in February 1884 that “Bill Crowley says his arm is well, and he threatens to play great ball for the Bostons this season.”23

Great ball he did play, posting his best batting season to date, belting six home runs and tying for the team lead with 61 runs batted in.24 Two of those home runs came in the span of a week against Old Hoss Radbourn of the Providence Grays, who was in the midst of his historic 60-win season, one baseball historians consider a prime candidate for the greatest pitching season of all time. On the negative side, on June 7 Crowley struck out to end Charlie Sweeney’s 19-strikeout game, a record that stood for 102 years until it was broken by Roger Clemens in 1986.25

Crowley primarily played right field for the Beaneaters, and was considered to be one of the finest fielders to ever grace the South End Grounds. This was no small feat, as the right-field foul pole at the Grounds was 255 feet from home plate, with 440 feet to the fence in right-center. Two years after his death, the Boston Globe claimed that “Jack Manning, Bill Crowley and Tom McCarthy are the only players that ever mastered the trick of playing right field on the Boston grounds.”26

Boston held the league lead as late as August 6, with a 50-20 record, a half-game ahead of Providence, but middling performance from the Beaneaters (23-18) and dynamic play from the Grays (35-8) down the stretch gave the National League crown to Boston’s close rival.

In November the Boston Globe reported that Crowley had signed with Buffalo, a decision that he claimed was due to being under the influence of alcohol and one he apparently regretted.27 Crowley shifted from right to left field, likely due to the arm issues that continued to plague him. The move failed to fully keep Crowley healthy, as he reportedly missed time due to the “old complaint” in the summer of 1885.28 With his arm deteriorating, and his bat going quiet – his .241 average in 1885 was the worst full-season mark of his career – Crowley (and the Buffalo Bisons for that matter) never played in the major leagues again.

Buffalo was bought out by the Detroit Wolverines, who now owned the rights to Crowley. His defense a far cry from where it was when he graced the South End Grounds, he was released by Detroit so he could negotiate with other clubs.29 A club from Macon, Georgia, showed interest, but Crowley was not keen on going south and believed he could find a better contract offer.

Nothing north of the Mason-Dixon line materialized, and Crowley indeed headed south to play for the Charleston (South Carolina) Seagulls of the Southern Association. He occasionally dazzled fans with phenomenal defensive plays,30 but his batting continued to decline and he was released in a cost-cutting measure by the end of July after batting .236 in 83 games.31

Crowley returned home to Gloucester, New Jersey, and did not receive an offer until April of the following year, when he was offered contracts by the Mobile Swamp Angels of the Southern League, and the Eastern League’s New Haven Blues.32 Crowley, familiar with New England and bearing an aversion to the South, opted to join the Blues, where he was named team captain.33

Crowley batted .350 for New Haven but reportedly was plagued by his reliance on alcohol. After the season a local paper reported that he was currently working in the oyster business, but “would like to sign again in some good town where intoxicating liquors are not sold.”34

Ten years after last playing in the International Association, Crowley was back, this time playing for the London (Ontario) Tecumsehs.35 The 1888 London club was made up of a few misfit parts, including diminutive hurler Larry Corcoran, who, like Crowley, had his best days behind him and a taste for liquor. By June 11 both were suspended for drunkenness, which assuredly hampered their play (Crowley batted .196 in 24 games, Corcoran posted a team-worst 5.36 ERA in 42 innings).36 The next week, the pair were sent packing.37

Within two weeks, Crowley had caught on with the Toledo Maumees of the Tri-State League where he played left field.38 His stay with Toledo did not last long, as he fell ill in mid-August, and returned home to New Jersey.39 His stint with Toledo was the last of his baseball-playing career, although he did manage and occasionally play in exhibition games with the Gloucester club, playing for one last time in April of 1890 against the Philadelphia Players League squad.40 A report from the time called Crowley “quite a sick man”41 and his name was rarely printed again until his death.

Much like former teammate Larry Corcoran, Crowley’s heavy drinking caught up with him, and he died of Bright’s disease (now commonly known as nephritis) at the age of 34 on July 14, 1891, at his home in Gloucester. Crowley was buried at St. Mary’s Cemetery in Bellmawr, New Jersey. He was never married and fathered no children. He was eulogized in the Philadelphia Inquirer as “a favorite with all ballplayers and managers,” and his funeral was said to be well-attended.42 The Buffalo Courier stated that “Crowley was a fine batsman, superior outfielder, a good catcher, and one of the best long and line throwers in the profession.”43

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and Ancestry.com

Notes

1 “Gloucester City Gleanings,” Courier-Post (Camden, New Jersey), July 15, 1891: 4.

2 “Catcher Crowley Dead,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 16, 1891: 3.

3 “Base Hits,” The Times (Philadelphia), April 10, 1875: 4.

4 “The Baseball Field,” The Times, May 20, 1875: 4.

5 “Philadelphia vs. Boston,” The Times, May 12, 1875: 1.

6 “Base-Ball,”Buffalo Morning Express, May 6, 1878: 4.

7 “Sporting Notes,” Buffalo Commercial, November 17, 1880: 3.

8 Hal Bock, Banned: Baseball’s Blacklist of All-Stars and Also-Rans (New York: Diversion Books, 2017), https://books.google.com/books/about/Banned.html?id=78sBDgAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&newbks=1&newbks_redir=1#v=onepage&q=crowley&f=false

9 “Convention at Philadelphia,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 14, 1882: 2.

10 “The Athletic Nine: The Other Players,” The Times, March 11, 1883: 3.

11 ”The Athletic Club wins a game over Yale,” The Times April 8, 1883: 2

12 “Athletic Averages,” The Times, May 6, 1883: 2.

13 “The Athletics Win,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 26, 1883: 2.

14 “Beaten by the Cincinnatis,” The Times, May 31, 1883: 4.

15 “Cincinnati vs. Athletic,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 31, 1883: 3.

16 “The Athletics Lose,” The Times, July 2, 1883: 1.

17 1883 Philadelphia Athletics, Baseball-Reference.com.

18 “Games To Be Played,” The Times, September 16, 1883: 2.

19 “The Morning Games,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 15, 1883: 2

20 “Forty-Four Victories,” The Times, September 21, 1883: 3.

21 “Gloucester’s Latest,” Camden Courier-Post, October 2, 1883: 1.

22 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, November 14, 1883: 3.

23 “Base Ball,” New Orleans Times-Democrat, February 4, 1884: 2.

24 Bill Crowley, Baseball-Reference.com.

25 Ed Achorn, “June 7, 1884: Charlie Sweeney Strikes Out 19 for Providence,” https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/june-7-1884-charlie-sweeney-strikes-out-19-for-providence/

26 “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, September 3, 1893: 7.

27 “Sporting Gossip,” Boston Globe, November 7, 1884: 5.

28 “Around the Bases,” Boston Globe, July 7, 1885: 2.

29 “Baseball Gossip,” Macon Telegraph, April 8, 1886: 3.

30 “The National Game,” Abbeville Press and Banner (Abbeville County, South Carolina), June 30, 1886: 2.

31 “One Base Hits,” Leavenworth (Kansas) Times, July 31, 1886: 4.

32 “Diamond Dust,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 14, 1887: 5.

33 “Sports in Season,” Sunday Truth (Buffalo, New York), June 5, 1887: 7.

34 “Will There Be a League?” Morning Journal-Courier (New Haven, Connecticut), December 13, 1887: 4.

35 “Local News Items,” Camden Courier-Post, February 1, 1888: 1.

36 “Close Decisions,” Boston Globe, June 11, 1888: 8.

37 “Base Ball,” New Haven Morning Journal-Courier, June 18, 1888: 4.

38 “Tri-State League Notes,” The Sun (New York), July 1, 1888: 6.

39 “Notes from Toledo,” Detroit Free Press, September 1, 1888: 8.

40 “Sporting Notes,” Camden Courier-Post, April 4, 1890; 1.

41 “Sporting Notes,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, March 18, 1890: 6.

42 “Gloucester City Gleanings,” Camden Courier-Post, July 17, 1891: 3. The “favorite” quote comes from Philadelphia Inquirer, July 16, 1891: 3.

43 “Diamond Glints,” Buffalo Courier, July 24, 1891: 8.

Full Name

William Michael Crowley

Born

April 8, 1857 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

Died

July 14, 1891 at Gloucester, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.