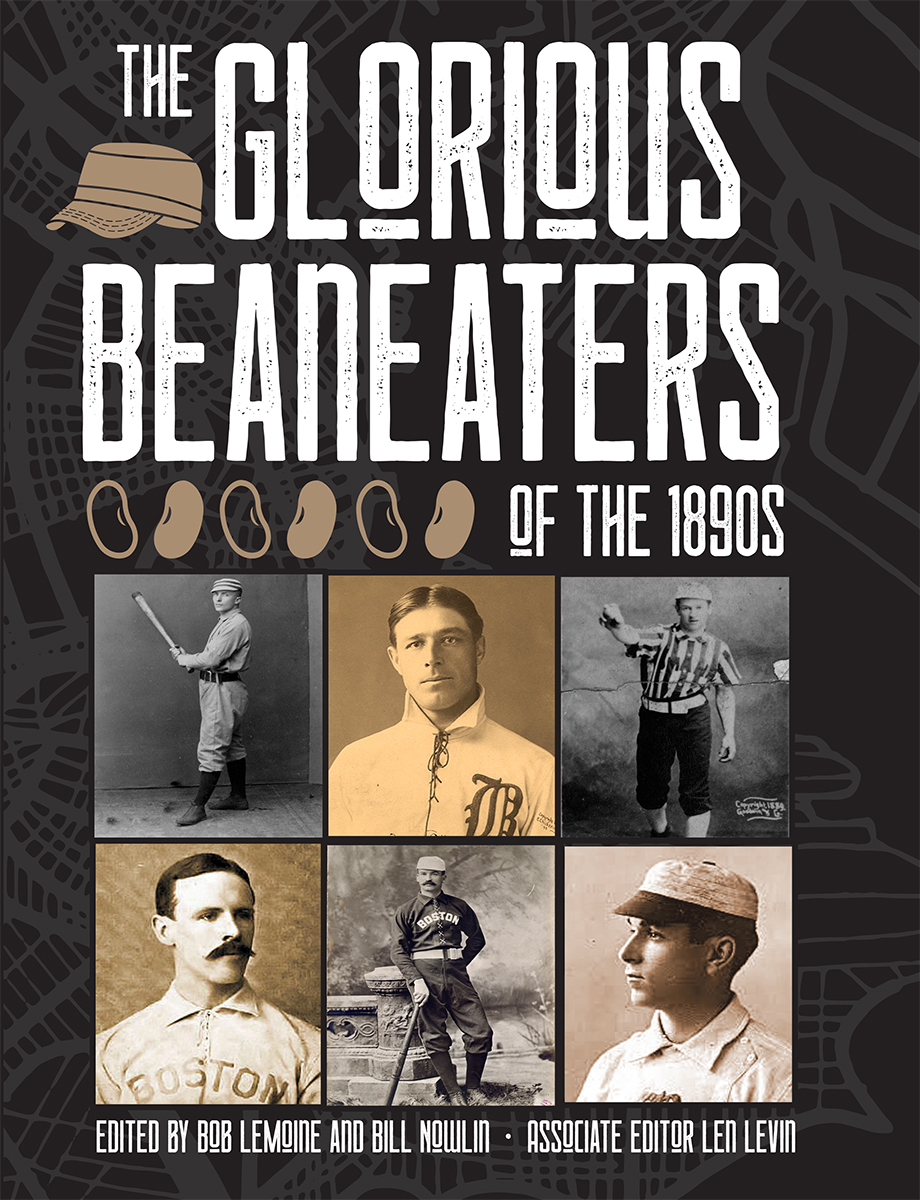

1891 Boston Beaneaters: 18 Straight Down the Stretch

This article was written by J.P. Caillault

This article was published in 1890s Boston Beaneaters essays

At the close of the 1890 baseball season the upstart Players’ League had died, the result of its owners bailing out on the players, leaving the National League and the American Association as the only remaining major leagues. And the climate surrounding those two leagues was far from peaceful.

At the close of the 1890 baseball season the upstart Players’ League had died, the result of its owners bailing out on the players, leaving the National League and the American Association as the only remaining major leagues. And the climate surrounding those two leagues was far from peaceful.

In Boston, in particular, there was open disagreement, as the Association wanted to place, for the first time in its 10-year history, a team in the Hub city. The AA expected that a Boston team would be able to sign to contracts for 1891 many, if not most, of the players who had played for the Boston Reds, the champions of the defunct Players’ League.

The NL Boston Beaneaters’ President, Arthur H. Soden, stated that he would not object to an AA team in Boston, but thought that both clubs would lose money. What Soden, and the other two-thirds of the Triumvirs (as the three men who owned the Beaneaters – President Soden, Director William Conant, and Treasurer James Billings – were known) were hoping to get, though, were some concessions from the Association in exchange for accepting an AA team in Boston. Namely, they wanted some of the players from the previous season’s Boston Reds roster: second baseman Joe Quinn, third baseman Billy Nash, and outfielder Hardy Richardson.1

The Triumvirs had run the Beaneaters franchise for several years. “Soden first got involved with the Beaneaters when he bought three shares of stock, at $30 per share, in the Boston League Base Ball Club back in 1876. Buying stock in a ball club then was done simply to help the game, as a dividend was never thought of. He became president of the club in 1878.”2

“Messrs. Billings and Conant, who are equal partners in the Boston league club, were baseball enthusiasts simply, until Mr. Soden got them to take stock. Mr. Billings became interested along about ’79, while Mr. Conant came to the front in ’83, the year Boston pulled off the league pennant for the last time.”3

In January of 1891, the AA announced that it would indeed place a team in Boston.4 Then, in early February, the Beaneaters made a shocking announcement – they had signed outfielder Harry Stovey, a longtime AA star and one of the main cogs in the previous season’s Boston Reds Players’ League championship team.5 This signing, along with that of second baseman Lou Bierbauer by the NL’s Pittsburgh club, caused an uproar throughout baseball.

The AA’s Philadelphia club, the Athletics, claimed that they owned the rights to Stovey and Bierbauer, since they had been under contract when they jumped to the Players’ League in 1890. Now that the Players’ League no longer existed, the Athletics claimed that the two players should return to Philadelphia under the rules of the reserve system in place under the so-called “national agreement” between the two major leagues (and the Western League, a high minor league).6

Meanwhile, Director Conant of the Beaneaters was discussing the possibility of getting superstar catcher Mike “King” Kelly to return to the team after his one-year hiatus with the Boston Reds.7 Kelly had played with the Beaneaters from 1887 to 1889 and was idolized by all of the baseball fans in Boston. Kelly was considered by most people in baseball to be the sport’s biggest drawing card and, possibly, its best manager and motivator, too, so getting him back was a high priority.

Then, in mid-February came a blitz of announcements that would shape the course of baseball in 1891 and beyond. On February 14 the National Board, the governing body overseeing all affairs of the leagues participating in the national agreement, ruled that Stovey was awarded to the Boston League club and Bierbauer to Pittsburgh (causing the team forevermore to be known as the “Pirates”). Soden was quoted as saying, “We have a perfect right to sign Stovey and will insist that he remain with us. Mr. Stovey would not play Sunday games, and was anxious to play with the league, and he was just the man we wanted.”8

The next day it was revealed that Allen W. Thurman, president of the American Association and one of the voting members of the National Board, had, shockingly, voted for the ruling favoring the League.9 (Thurman was summarily dismissed as AA president, replaced by Louis Kramer.10) Two days later, there was an announcement that Kelly would captain the Association’s new Cincinnati club, permitted to go there by the management of the Boston Reds.11 And then the following day, National League President Nick Young received official notification from the AA of its withdrawal from the national agreement, precipitated, of course, by the ruling of the National Board.12

This set up a “war” between the two leagues that would have a major impact on the possibility of a world’s series between the champions of the Association and the League at the end of the 1891 season and, more importantly, set the stage for the ultimate demise of the Association and the League’s monopoly and syndication of major-league baseball throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century.

In early March the Beaneaters acceded to the financial demands of Billy Nash (reportedly $5,000 for each of the next three seasons plus a signing bonus of $2,500) and signed him as their third baseman and captain.13 And in late March the members of the team started slowly trickling into town to begin preparing for the season. The Beaneaters used the YMCA gym on Boylston Street when the weather was bad and practiced at the South End Grounds when the weather was pleasant.14

Boston planned a big preseason exhibition game for Fast Day (April 2), the Beaneaters hosting John Ward’s Brooklyn AA team, known as “Ward’s Wonders.”15 More than 6,000 fans came to the South End Grounds and saw the League team whip Brooklyn, with Stovey hitting a home run and stealing a couple of bases in his Beaneaters debut.16 The regular season was still weeks away, and, wrote the Boston Globe, “it was a very cold day, but it was Fast day, the bell had rung, the umpire was all ready to shout ‘play ball,’ and another season of the glorious old sport was about to begin.”17

Tim Murnane, the Globe’s prominent sportswriter, saw the Reds as heavy favorites to win the American Association pennant, but in the National League he thought the Giants were the best team, with Chicago and Brooklyn not far behind. As for the local team, Murnane said, “How about Boston? Oh, the Bostons can play ball, but I am a few chips shy when putting the team down for pennant winners. If the men should all work together, without an eye for individual records, they will most likely get into the first division.”18

Boston opened its National League season on Wednesday, April 22, in New York, where the heavily favored Giants hosted the Beaneaters in front of a huge crowd of 17,000. The game was a close pitchers’ duel between Boston’s veteran ace John Clarkson and the Giants’ young, fireballing Amos Rusie. The Beaneaters won in the ninth inning, 4-3, on a fly ball hit by shortstop Herman Long that Giants center fielder George Gore misplayed.19 Three days later, Boston had completed a four-game sweep of the stunned Giants and stood tied for first place with the Cleveland Spiders.

On Monday, April 27, a large crowd of 7,500 showed up at the South End Grounds to see Boston’s first home game of the season. The story was the lead on the Boston Globe front page and even included an illustration of Massachusetts Governor William Russell arriving at the game.20

The Beaneaters’ young ace, Kid Nichols, threw a five-hit shutout and Stovey hit two doubles and a triple as Boston beat Philadelphia, 5-0.21 Boston ended up only splitting that four-game series with Philly, but they were still in first place, a game ahead of three other teams.

The Beaneaters then split four games in Brooklyn, but were still tied for first place with Cleveland, a half-game ahead of Chicago. Murnane expressed his strong opinion that the team was already in desperate need of an additional pitcher, as third starter Charles “Pretzels” Getzien, who had pitched well for the Beaneaters in 1890 and for Detroit previously, had declined rapidly and was simply not capable of filling in adequately when Clarkson and Nichols needed rest.22

There was a lot of excitement in the Hub at the beginning of May, as King Kelly’s “Killers” visited the Reds at the Congress Street Grounds, while Buck Ewing’s Giants came to the South End Grounds, hoping to gain some revenge on Boston for having swept New York in their season-opening series.

The Giants won two out of three, as Boston tried out new pitchers John Kiley and Cyclone Ryan during the series (neither of whom ever pitched in the majors again). On May 10, as the Beaneaters prepared to travel for a long trip out West, where they were scheduled to play four games against each of the four Western teams, they found themselves in second place, one game behind Cap Anson’s Chicago club.

John Clarkson pitched Boston to a series-opening win in Chicago, aided by Stovey’s fourth-inning homer that was “hit far over the outer wall among the bitter weeds.”23 Despite a sterling second game from Stovey (another homer, plus three assists, throwing out runners at second, third, and home), the Colts pounded Kid Nichols.24 The two teams split the next two games, too, so the Beaneaters still trailed by one game when they left Chicago for Cincinnati.

The last-place Cincinnati team called on “Old Charley” (also called “Old Hoss”) Radbourn to beat his former team twice in the series (Radbourn had pitched for Boston for four years before jumping to the Boston Reds of the Players’ League). The Beaneaters, having lost three of four in Cincinnati, then lost three of four in Cleveland, with Cy Young outdueling Kid Nichols in one game that was controversially called because of darkness, causing captain Billy Nash to make “a vigorous protest, but it was of no avail.”25

As the Beaneaters finished up their road trip in Pittsburgh, their need for additional pitching was made all the more clear during the three games with the Pirates, as Nichols and Clarkson won their games, but new pitcher Charles Brynan lasted but one inning and never pitched in the major leagues again.26

On May 27, in what turned out to be a critically important move, Boston obtained from the Pirates 24-year-old Harry Staley, a workhorse who had started nearly 50 games and pitched around 400 innings in each of the previous two seasons.27 It is worth noting that Pittsburgh’s record on this date was 15-12, putting them in second place, three games behind Chicago. They would finish last. And the Beaneaters on that day were in fifth place, closer to cellar-dwelling Cincinnati than to first place Chicago.

Decoration Day (now called Memorial Day) on May 30 marked the first notable holiday of the season, celebrated with doubleheaders in both leagues. At the South End Grounds, 4,000 people attended the morning game, while 10,000 saw the afternoon game.

The Beaneaters swept their two games from Cincinnati, Staley winning his Boston debut in the first game, while Clarkson beat Radbourn in the second. The Boston Globe report gushed about Staley’s work “in the box,” but was especially nostalgic about Radbourn and his mid-1880s glory days with the Providence Grays:

“The real sendoff of the game was given to Old Hoss Charley Radbourn as he walked from the bench to take his position in the box before the game,” wrote the Globe. “‘Rad’ tipped his cap and handled the ball nervously as the crowd cheered. The bronzed old warrior of the diamond felt the blood come to his cheek when he stood on the spot he had made famous but a few years back when he was the main stay of that Rhode Island champion team in the stubborn contests with the Bostons when games lengthened out in to 14 and 16 innings and the score of both teams seldom reached five in all.

“The day as a whole was a base ball success, from the jingle of the half dollar and the merry tick of the turnstile to the smile of the honest face of William Nash.”28

At the end of May, the National League standings saw Boston in a five-team logjam, 3½ games behind first-place Chicago.

In early June Harry Stovey missed five games to be at home with his family, tending to his two-month-old daughter,29who died on June 6 (her twin was stillborn on April 1).30 The Beaneaters lost three of those games and were 4½ games back when Cap Anson’s first-place Chicago Colts made their first visit to the South End Grounds.

“Anson is willing to wager anything, from a chew of tobacco to a dress suit, that his Chicago nine can beat any team in the league for a place, and with a little odds will take his team for a pennant winner,” wrote the Globe. “The Chicago team has always been the leading attraction in this city, and the next four games will be a test of the drawing power of our league team this season. Bill] Hutchinson and Clarkson will most likely do the pitching. Hutchinson is looked on as a wonder, and is doing half the pitching for his team.”31

The attendance at the South End Grounds totaled 12,000 for the four-game series, which the two teams split, Hutchinson and Clarkson each winning one of their two duels.

The New York Giants, meanwhile, were surging. By mid-June, after having swept four games from visiting Chicago, including a Saturday game in front of a record 22,289 fans at the Polo Grounds, to run the Colts’ losing streak to six games, the Giants had won 15 of 16 and were in first place, four games ahead of Chicago and 4½ ahead of Boston.

On June 17 Boston hosted a doubleheader to celebrate Bunker Hill Day, but the cold, wet weather kept the attendance down to about 2,000 for each of the games at the South End Grounds. The Beaneaters beat visiting Brooklyn’s “Ward’s Wonders” twice, Nichols and Staley picking up the wins.

Although Cincinnati’s “Kelly’s Killers” were playing .500 ball in the Association and drawing decent crowds, there was talk of Mike Kelly coming back to Boston. Chicago’s Anson was quoted as saying the Bostons should never have let him go, since Kelly was “one of the greatest ball players in the business and the best drawing card that Boston ever had. It was a big mistake to let him leave the league. With Kel in the Boston team the crowds at the South End grounds would have been just double.”32

The Cincinnati Commercial Gazette reported on what it saw as Boston’s motive: “By getting Kelly away from Cincinnati they would serve a double purpose in breaking up the association club in this city and in adding to their own team one of the most popular players that ever set foot on a ball field. Capt. Kelly today is rated as one of the greatest players in the profession, and he hasn’t an equal as a drawing card.”33

With nothing but rumors about Kelly swirling, the Beaneaters wrapped up their long homestand winning 13 and losing 7, tied for second place with Chicago, 2½ games behind New York. They then left, on June 21, for Philadelphia, embarking on a 3½-week road trip in which they would visit every other team in the league.

Boston won its first game on the trip with Clarkson handling the imposing Phillies’ lineup that included future Hall of Fame outfielders Billy Hamilton, Sam Thompson, and Ed Delahanty, but the Beaneaters then lost the next three in Philly.

They then moved on to another showdown with the Giants in New York. The first scheduled game was rained out, but Clarkson beat Rusie in the second game in front of a large Saturday crowd of more than 7,000. With no Sunday game scheduled, as usual in the NL, Roger Connor and Jim O’Rourke each got three hits off Clarkson on Monday and the Giants beat Boston to split their two games.

The last day of June saw Stovey suffer the ignominy of striking out five times in one game, against Brooklyn’s George Hemming, becoming only the second player ever to do so (the first was the Buffalo Bison’s Oscar Walker in 1879).34

At the end of June the Beaneaters were in third place in the National League, 4½ games behind first-place New York and 3½ behind second-place Chicago.

The Beaneaters played their July 4 holiday doubleheader in Pittsburgh, in front of crowds of more than 5,000, and came away with two wins, Clarkson and Staley beating Silver King and Mark Baldwin. The Giants also won twice on the road, winning in Cincinnati, while the Colts, playing at home in front of crowds of 6,682 and 11,117, lost both ends of their doubleheader against visiting Brooklyn.

There were still plenty of rumors going around about the Beaneaters reacquiring Mike Kelly, especially since Boston manager Frank Selee was said to be disgusted with first baseman Tommy Tucker’s play, both hitting and fielding. Murnane thought that Tucker was not putting up the game that was expected of a man getting a salary of over $4,000. Director Conant, “a warm friend” of Kelly’s, and manager Selee wanted Kelly back, but President Soden and Treasurer Billings were not keen on his return.35

By the middle of July, the National League pennant race had narrowed down to three contenders: New York, Chicago, and Boston. And the second-place Colts, having just lost two of three at home to the first-place Giants, welcomed the third-place Beaneaters for a three-game set. Chicago won the first game easily, with Ad Gumbert shutting out Boston, but each of the next two games went to extra innings before the Beaneaters succumbed. The last game was described as the most exciting of the season. Boston had taken a two-run lead in the top of the 12th inning, but in the bottom of the inning, with two on and two out, a pop fly fell just in front of Stovey, whose throw to the plate “went against the stand, all three men scoring and the game was won before the crowd realized what had happened.”36 And with that sweep, at the midpoint of the NL season, Chicago jumped back into first place.

The Beaneaters’ long 3½-week road trip, during which they won 10 games and lost 10, was finally over. “Staley, Nichols, and Clarkson were the back bone of the team, Kid Nichols doing phenomenally good work in the box,” wrote the Globe.37 With the exception of a brief series in Philadelphia scheduled for the end of July, Boston would be welcoming all of the other NL teams at the South End Grounds over the next month.

After getting swept in Chicago, Boston bounced back during the last two weeks of July and the first week of August, winning 10 of 13 games and jumping into second place ahead of New York and trailing Chicago by only 1½ games, just in time for Cap Anson’s team’s visit to the Hub city.

The first game, on Thursday, August 6, played before a South End Grounds crowd of more than 5,000 fans, ended in the 13th inning when Nichols hit a Chicago batter with the bases loaded, forcing in the winning run. The loss dropped Boston back into third place.

The next day the Colts, behind their workhorse pitcher Hutchinson, won in extra innings again. The Beaneaters finally won on Saturday, in front of nearly 9,000 enthusiastic fans: “It was one of the old-time crowds that witnessed the game yesterday at the South End grounds,” the Globe noted. “About every seat in the pavilion and on the bleachers was taken.”38

By the middle of August, with Boston having concluded its long homestand by winning four of its last five games, and with Chicago losing two of three in New York, the National League race was as tight as it could be, with the Colts in first place, a half-game ahead of the second-place Beaneaters, and one game ahead of the third-place Giants.

Boston then left for its last long road trip of the season, a three-week tour of every NL city but Philadelphia.

At their first stop, in New York, the Beaneaters took two of three from the Giants, permanently relegating the Giants to third place in the NL pennant race. During their next stop, in Brooklyn, Harry Stovey again fell to the curse of Brooklyn’s George Hemming, striking out against him four times, almost equaling the five times Stovey fanned against Hemming back at the end of June. While on the next leg of their road trip, in Pittsburgh, there was a big headline on the front page of the August 26 edition of the Boston Globe:

“Kelly Jumps. Will Play with Boston League Team.”39

Mike Kelly signed a contract that would pay him $25,000 from that date to the end of the following season. It was the “largest salary ever paid to a ball player.”40

Director Conant said, “Well, the King is home again. He’s back with the club he first started with in Boston. He has cost a good deal of money, but he is worth it, and he is the greatest drawing card in the base ball profession. Just imagine the people who will go to see him in Chicago when he gets there.”41

There were, not surprisingly, major repercussions to this announcement. Coincidentally, representatives of the National League and American Association were meeting in Washington to try to hammer out a new national agreement, but the news about Kelly caused Association President Kramer to call a halt to the conference. “Breach is widened” was the subheadline in the Globe.42

And Globe columnist Tim Murnane couldn’t resist making this snide remark: “If Mike Kelly has signed with the league he will probably play with one arm, as he took an oath some time ago that he would cut off his right wing sooner than sign with the league.”43

Overshadowed by the controversial news about Kelly signing with the League and his reappearance in the Beaneaters’ lineup beginning with the games in Cleveland, the Beaneaters won only half of their games over the last two weeks of their road trip, and fell from a half-game back of the Colts to five games back when they arrived in Chicago for a three-game series in early September.

In the first game between the two remaining NL pennant contenders, Chicago walloped Boston, 10-1, Bill Hutchinson limiting the Beaneaters to just two hits.44 The next day, “Anson created a sensation by appearing on the field with flowing whiskers of snowy whiteness and long white hair. He played the game through in this disguise and the crowd seemed to enjoy the sight.”45 And Chicago won again, expanding its lead over Boston to a seemingly irretrievable seven games. The Beaneaters managed to salvage a small sense of pride by beating the Colts in the last game of the series, wrapping up their 19-game road trip with 10 wins and 9 losses. They then headed home, where they would host all of the League’s teams at the South End Grounds over the last four weeks of the season.

Despite being so far behind Chicago in the standings, “Manager Selee said that nothing would please him more than to see the Boston league and association teams playing a series for the world’s championship this fall. This would please the patrons of base ball in this part of the country more than any other thing the magnates could do.”46

The Labor Day doubleheader at the South End Grounds was rained out, but the Beaneaters played back-to-back doubleheaders against visiting Cleveland over the next two days, winning three of four. They then swept three games from visiting Cincinnati, reducing Chicago’s lead to 4½ games as the Colts arrived in Boston for their last visit.

In front of a large Monday crowd of more than 6,000 at the South End Grounds on September 14, Chicago’s “Cannon-ball Willie” Hutchinson beat the Beaneaters again, holding them to just three hits for his 42nd victory of the season. Chicago won again the next day, John Clarkson getting roughed up by the Colts. Chicago had extended its lead to 6½ games and the Boston Journal said, “The Bostons might as well at once give up all hope of winning the championship this year. In the first place there are too few games to play to catch up with Anson; in the next place, they must play a far better game than they have shown of late to be able to cope with any team of the ability of the Chicagos.”47

When Boston finally beat Chicago on September 16, Nichols beating Hutchinson, little did anyone know that the Beaneaters had begun what would turn out to be the most remarkable pennant-grabbing stretch-run sprint in baseball history.

After having a tied game called on account of darkness, Boston won three straight from Pittsburgh at the same time that New York was sweeping three from Chicago, Giants workhorse Amos Rusie winning two of the games.

The Beaneaters then took four in a row from visiting Brooklyn, followed by a three-game sweep of Philadelphia. The Colts pretty much kept up, winning all five of their scheduled games. Chicago’s 1½-game lead looked somewhat tenuous, but as they headed into the last week of the season, the Colts’ final two series would be with sub-.500 teams: fifth-place Cleveland and tail-ender Cincinnati. Boston, meanwhile, would have to face two teams with winning records: the third-place Giants and the fourth-place Phillies.

Then came the controversial series that would forever cast a shadow over the accomplishments of the 1891 Boston Beaneaters team. The New York Giants came to the South End Grounds a bit battered and lackadaisical after having been eliminated in the pennant race. In the first game of the series, the Giants sent 23-year-old Roscoe Coughlin to the pitcher’s box to face the Beaneaters. Coughlin was making only his fifth start of the season. Star first baseman Roger Connor and starting catcher Dick Buckley were not in the lineup for the Giants as they were pummeled by the Beaneaters, 11-3. The skepticism about the integrity of the Giants’ effort began right in Boston, as the Reds’ “Billy Joyce was at the South End grounds yesterday and said: ‘I wonder if that’s the team Jim] Mutrie [manager of the Giants] would put against the Reds for $1,000? Why, that crowd of Giants couldn’t beat nine schoolboys.’ ”48

Chicago, meanwhile, lost to the Spiders, with Cy Young beating Bill Hutchinson, so the Colts’ lead was down to a half-game.

More than 5,000 fans showed up for Tuesday’s doubleheader, as they saw the Beaneaters easily take both games from the Giants. Although New York had aging veteran Mickey Welch pitch the first game, its pitcher for the second game was Mike Sullivan, who was making his first-ever start for the team. Connor and Buckley were still missing from the Giants’ lineup, while Bobby Lowe and Harry Stovey led a barrage of hits against both Welch and Sullivan as Boston won, 13-8 and 11-3.49 Even Tim Murnane was disappointed in the way that the Giants were playing, writing, “The same teams play two games this afternoon, and the Giants should put a little more life into their work if they wish base ball to hold its present high standing among outdoor games.”50

Chicago won a wild back-and-forth game in Cleveland, 14-13, winning in the bottom of the ninth inning, but the Colts and Beaneaters were now in a virtual tie, Chicago leading by the smallest of margins in winning percentage (.626, 82-49 for the Colts vs .624, 83-50 for Boston).51

On the last day of September, more than 4,000 fans came to the South End Grounds to see Boston’s last home games of the season. The Beaneaters again won both games of a doubleheader, beating New York 16-5 and 5-3, running their winning streak to 16 games. Although Connor returned to the Giants’ lineup, star outfielder Hardy Richardson was absent, and the Giants started Coughlin in the first game and Sullivan in the second, a far cry from aces Amos Rusie (33-20 for the season) and John Ewing (21-8). And Chicago was again beaten by Cy Young, so, for the first time since early May, the Beaneaters moved into sole possession of first place, 1½ games ahead of the slumping Colts. The Globe effused, “The Boston league team wound up the season of ’91 at the South End grounds yesterday by taking two games from New York and going to the front in the greatest struggle known in the history of base ball.”52

President James Hart of the Chicago club was irate. That same day, Wednesday, September 30, he wrote to National League President Nick Young asking whether prior consent had been given for Boston to play all of those doubleheaders it had played recently at the South End Grounds (September 19 with Pittsburgh, September 23 with Brooklyn, and September 29 and 30 with New York). According to Hart, consent had to have been granted by six clubs prior to the games having been played. If consent had not been given, then Hart wanted the games “declared void and thrown out of the championship table and the decision made public in tomorrow morning’s papers.”53

The Globe reported that Hart later said: “Public sentiment is running high, and it seems to favor the idea that the Eastern clubs are not playing as well as they might. I have no accusations to make against anybody, but I will say that things do look suspicious.”54

On October 1, the Beaneaters clinched the pennant, with Clarkson beating the Phillies for Boston’s 17th consecutive win. In Chicago, meanwhile, in front of only 2,000 resigned fans, “Cincinnati won from Anson’s men today partly because Tony] Mullane was in wonderful form and partly because the Chicagos manifestly played like men fighting for a lost cause. All of their ginger is gone, and the game was as dreary a thing as one could wish to see, particularly after the score board had announced another Boston victory.”55

Two days later, there was a report from Chicago that “President James A. Hart of the Chicago club today received a telegram from Nick Young, telling him that every club but Chicago had given its consent to the extra games played by the Boston club lately.

“When he received this, Mr. Hart resolved on his course of action at once. On Monday he will forward to President Young formal charges of crookedness on the part of New York in their last games with Boston. ‘I shall probe the matter to the bottom,’ was Mr. Hart’s parting shot.”56

The following day the headlines on the front page of the Globe lauded the Beaneaters: “The league champions of 1892 will hail from Boston. It has been some time since Boston pulled off the league pennant, although they have made a good fight for the last three years. This year it looked almost impossible to overtake Capt. Anson’s Chicago team, but the boys set about the task three weeks ago, and the magnificent work they did from that time until Chicago was passed and the pennant landed was never surpassed in this country.

“To Capt. William Nash and Manager Frank Selee belongs the most credit for bringing the honor to this city. Selee got out all the play there was in his men, and saw they needed a pitcher, when Staley was secured.”57

As for the possibility of the two Boston champions playing a series to decide the world’s championship, an article from Washington stated that NL President Nick Young had received a dispatch from AA President Zach Phelps saying, “The pennant club of the Association hereby challenges the pennant club of the League to play a series of three, five, or seven games for the world’s championship.”58

The Reds, who featured future Hall of Fame sluggers Dan Brouthers and Hugh Duffy, led all of major-league baseball in runs scored. The Beaneaters, meanwhile, allowed the fewest runs in the NL, thanks to their star pitchers John Clarkson (33-19, 2.79), Kid Nichols (30-17, 2.39), and Harry Staley (20-8, 2.50). What an incredible series it would have been for the Hub – a baseball version of the irresistible force versus the immovable object!

However, the series never occurred, as President Young replied to Phelps, “I hold in my possession an agreement called the national agreement, which was solemnly signed by three parties, one of which was your association. I sincerely regret that the breaking of that agreement by your association renders such a series of games as you propose impossible.”59

Two days later, on October 12, the Globe published a letter to the Boston Reds club from President Phelps, saying that he had challenged the NL champs to a world’s series, but they declined. He also said that the club itself challenged the Boston NL club and they declined. He then mocked the NL’s excuse of using the national agreement. “There can, of course, be no agreement except there be at least two parties thereto, and the league alone is now party to what they are pleased to call the ‘national agreement.’ ”60

The next day the committee assigned to investigate the charges brought against the New York Giants by President Hart of the Chicago club submitted its final report, exonerating all involved. The report concluded that the Giants’ poor showing was attributable to their crippled condition. The committee thus determined that the charges of deliberate bad faith were unfounded and the committee regretted that full credit for having won the championship in such spectacular fashion was withheld from Boston as a result of the charges made by Chicago.61

The season of 1891 was arguably the city of Boston’s greatest in its long, rich major-league history. The controversy surrounding the existence of two teams in the city, the weaving throughout the season of the story of favorite son Mike “King” Kelly, the unprecedented stretch run, pennant-grabbing, 18-game winning streak of the Beaneaters, and the unresolved argument as to which team was better, the American Association champion Reds or the National League champion Beaneaters, all made the season among the most memorable ever.

JEAN-PIERRE CAILLAULT has been a Professor of Astronomy at the University of Georgia for 32 years. He joined SABR in 1984, when, as a PhD student at Columbia University, he made his first SABR presentation to the Casey Stengel Chapter (NYC) at the Shea Stadium Diamond Club. He has since written articles for Baseball Digest and SABR’s Baseball Research Journal, a chapter for Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century (SABR 2013), and two books on 19th-century baseball: A Tale of Four Cities (McFarland & Co., 2003) and The Complete New York Clipper Biographies (McFarland & Co., 2009). His presentation at the 2010 SABR National Convention in Atlanta was awarded the USA Today Sports Weekly Award for Best Poster Presentation. He is an avid collector of baseball cards, owning the complete set of Topps cards for every season dating back to 1957.

Notes

1 “League Men Object,” Boston Globe, January 14, 1891.

2 T.H. Murnane, “He Loves the Game,” Boston Globe, August 1, 1891.

3 Ibid.

4 “Untangling the Tangle,” Boston Globe, January 16, 1891.

5 T.H. Murnane, “Two Stars Sign,” Boston Globe, February 6, 1891.

6 T.H. Murnane, “Pick of the Stars,” Boston Globe, January 18, 1891.

7 Ibid.

8 T.H. Murnane, “War Declared,” Boston Globe, February 15, 1891.

9 T.H. Murnane, “Base Ball War,” Boston Globe, February 16, 1891.

10 “Kranmer [sic] at the Helm,” Boston Globe, February 19, 1891.

11 “In War Paint,” Boston Globe, February 18, 1891.

12 “Kranmer [sic] at the Helm.”

13 “Big Money Got Him,” Boston Globe, March 8, 1891.

14 T.H. Murnane, “Experts at Practice,” Boston Globe, March 26, 1891.

15 T.H. Murnane, “How They Pitch,” Boston Globe, March 30, 1891.

16 J.C. Edgerly, “Boston on Top,” Boston Globe, April 3, 1891.

17 Ibid.

18 T.H. Murnane, “Murnane Sizes Them Up,” Boston Globe, April 20, 1891.

19 “Grand Send Off,” Boston Globe, April 23, 1891.

20 “Five Straight,” Boston Globe, April 28, 1891.

21 Ibid.

22 T.H. Murnane, “Trying Point Reached,” Boston Globe, May 4, 1891.

23 T.H. Murnane, “One on ‘Anse,’” Boston Globe, May 12, 1891.

24 T.H. Murnane, “Hoss and Hoss,” Boston Globe, May 13, 1891.

25 T.H. Murnane, “When Hits Would Tell,” Boston Globe, May 23, 1891.

26 T.H. Murnane, “Costly Experiment,” Boston Globe, May 27, 1891.

27 “Staley Signs With Boston,” Boston Globe, May 27, 1891.

28 ”Off His Fodder,” Boston Globe, May 31, 1891.

29 “Tried Two Pitchers,” Boston Globe, June 3, 1891.

30 Jean-Pierre Caillault, personal notes for future biography of Harry Stovey.

31 “Chicago Today,” Boston Globe, June 8, 1891.

32 T.H. Murnane, “They Are After Kelly,” Boston Globe, June 19, 1891.

33 Ibid.

34 Joseph L. Reichler, The Great All-Time Baseball Record Book (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1981), 92.

35 T.H. Murnane, “Wanted ‘King Kel’ Back,” Boston Globe, July 4, 1891.

36 “Played Twelve Innings,” Boston Globe, July 17, 1891.

37 “On Their Native Heath,” Boston Globe, July 18, 1891.

38 T.H. Murnane, “Anson Was Merciful,” Boston Globe, August 9, 1891.

39 J.C. Edgerly, “Kelly Jumps,” Boston Globe, August 26, 1891.

40 Ibid.

41 Ibid.

42 T.H. Murnane, “Breach Is Widened,” Boston Globe, August 26, 1891.

43 T.H. Murnane, “New Agreement Needed,” Boston Globe, August 26, 1891.

44 “Downed Again,” Boston Globe, September 4, 1891.

45 “Bostons Not in It,” Boston Globe, September 5, 1891.

46 “Leaguers at Home,” Boston Globe, September 8, 1891.

47 “Both Beaten,” Boston Journal, September 16, 1891.

48 “Base Ball Notes,” Boston Globe, September 29, 1891.

49 T.H. Murnane, “Won Both in a Canter,” Boston Globe, September 30, 1891.

50 Ibid.

51 Ibid.

52 T.H. Murnane, “Forged Ahead,” Boston Globe, October 1, 1891.

53 “ ‘Things Look Suspicious,’ ” Boston Globe, October 1, 1891.

54 Ibid.

55 “Still They Win,” Boston Globe, October 2, 1891.

56 “President Hart’s Action,” Boston Globe, October 4, 1891.

57 “Champions of ’92,” Boston Globe, October 5, 1891.

58 “League Club Cannot Play,” Boston Globe, October 10, 1891.

59 Ibid.

60 “Champions of the World,” Boston Globe, October 12, 1891.

61 “Exonerate All,” Boston Globe, October 14, 1891.