Even Against Hall of Fame Hurlers, Babe Ruth Was King of Swing

This article was written by Ed Gruver

This article was published in The Babe (2019)

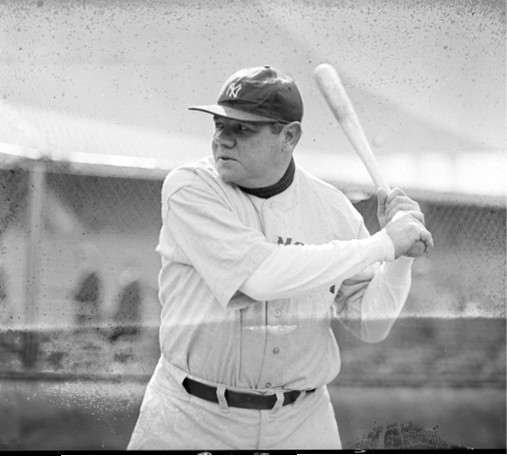

Babe Ruth strikes a batting pose at Fenway Park in the early 1930s. (Leslie Jones photo, courtesy of the Boston Public Library.)

Even among Jazz Age giants like Al Jolson and Jack Dempsey, it was Babe Ruth who was the King of Swing.

“I swing as hard as I can, and I try to swing right through the ball,” Ruth was quoted as saying. “I swing big, with everything I’ve got. I hit big or I miss big. I like to live as big as I can.”1

Ruth roared through the Roaring Twenties, the most famous sports figure in an era that included Dempsey, the ferocious heavyweight champion; gridiron great Red Grange; Notre Dame football coaching legend Knute Rockne; gentleman golfer Bobby Jones; and tennis star Big Bill Tilden.

Ruth rose above them all, his home-run hitting heralding the Lively Ball Era and enthralling everyone from legendary writers Grantland Rice and Damon Runyon to politicos like President Calvin Coolidge and New York Governor Franklin Roosevelt. The Babe’s big swing terrorized opposing pitchers, be it regular season, World Series, All-Star Games, or exhibition contests against Negro League and Cuban stars. His home runs were so majestic that no ballpark could contain them, a fact that awed even a Hall of Fame pitcher who was a teammate of The Bambino.

“No one hit home runs the way Babe did,” former Yankees ace Lefty Gomez said. “They were something special. They were like homing pigeons. The ball would leave the bat, pause briefly, suddenly gain its bearings then take off for the stands.”2

There were many outstanding hurlers in Ruth’s era, but how did The Sultan of Swat fare against the greatest pitchers of his generation? In his 22-year career, The Babe faced 13 future Hall of Fame pitchers, or 14 depending on which story you believe regarding Ruth hitting against Negro Leagues legend Satchel Paige.

In regular-season play, The Babe batted against Hall of Famers Stan Coveleski, Dizzy Dean, Red Faber, Lefty Grove, Waite Hoyt, Carl Hubbell, Walter Johnson, Ted Lyons, Herb Pennock, and Red Ruffing. His lone All-Star Game matchup with a Hall of Famer came against Hubbell. Ruth’s World Series showdowns with HOF pitchers saw him hit against Pete Alexander, Burleigh Grimes, and Jesse Haines.

Coveleski, a tall, lean right-hander, broke into the big leagues in 1912 with Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics. He returned to the majors in 1916 with the Cleveland Indians and spent the next 13 seasons in Cleveland and Washington before teaming with Ruth on the Yankees’ 1928 World Series squad. Coveleski won 20 or more games in a season five times, including four straight from 1918 to 1921.

He claimed a career-best 24 victories in 1919 and matched it the following season. On May 24, 1918, Coveleski hurled a 19-inning complete-game victory over the Yankees and in 1920 won Game Seven of the World Series for the Indians. Teammate and fellow Hall of Famer Joe Sewell said Coveleski threw a spitball that broke from a hitter’s head to the ground and that trying to hit it was like trying to hit a butterfly. Coveleski closed his career with a 215-142 record and a 2.89 earned-run average.

Ruth recorded 86 at-bats against Coveleski and collected 30 hits for a .349 batting average. Among his hits were three home runs, nine doubles, and a triple. Coveleski walked Ruth 37 times and struck him out 10 times.

Ruth’s matchups with Dean were heralded but disappointing for The Babe. When The Bambino batted against Dean in 1935, Ruth was 40 years old, overweight, and wearing the uniform of the Boston Braves.

Dean’s lifetime record – 150-83 with a 3.02 ERA – scarcely does justice to the skills of the hard-throwing right-hander. A celebrated 30-game winner in 1934, Diz finally got to face The Babe in official at-bats on Sunday, May 5, at Braves Field. A crowd of 30,000 watched the former symbol of the Yankees’ Murderers’ Row dig in against the ace of the reigning World Series champion Gas House Gang.

Ruth’s three plate appearances included an 0-for-2 with a strikeout and walk. Dean won the game, 7-0, and it was he rather than Ruth who homered that afternoon. Ruth and Dean met again on May 19 in St. Louis’s Sportsman’s Park. The Babe went 0-for-4 with a strikeout as Diz again went the distance, this time in a 7-3 victory. Ruth’s batting record against Dean was 0-for-6 with one walk and two strikeouts.

Faber spent his 20-year career with the Chicago White Sox, going 254-213 with a 3.15 ERA from 1914 to 1933. The right-hander won 20 or more games four times, including a career-high 25 in 1921 to highlight a stretch of three straight 20-win seasons. Ruth struggled against Faber, hitting .247 in 158 at-bats. Still, The Babe had his moments, totaling 39 hits and 7 home runs. He worked Faber for 28 walks but fanned 27 times.

Ruth had less difficulty dealing with the greatest left-hander of his era – Grove. The ace of Mack’s second Athletics dynasty and later of the Boston Red Sox, Grove was 300-141 with a 3.06 ERA in a 17-year career from 1925 to 1941. He won at least 20 games eight times, including seven straight seasons from 1927 to 1933. The hard thrower peaked in 1931 when he went 31-4 with a 2.06 ERA. Against Grove, Ruth batted .316 with 42 hits in 133 at-bats. He homered nine times. Grove had his say as well, fanning The Bambino 45 times.

Ruth faced several former and future teammates, and three of them – Hoyt, Pennock, and Ruffing – won world championships with him in New York. Hoyt was the right-handed ace of the Yankees’ championship squads of 1927-28, winning 45 games in that two-year span. He went 237-182 with a 3.59 ERA in a 21-year career from 1918 to 1938. Ruth’s initial at-bats against Hoyt came early in The Babe’s career in New York when Hoyt was with the Red Sox in 1920. They opposed each other again in 1930-31 when Hoyt was with Detroit and the Athletics, and finally in 1935 when Hoyt hurled for Pittsburgh.

Nicknamed “Schoolboy,” Hoyt was “the man” in the clutch, posting a 1.83 ERA in the World Series and winning six of his 10 decisions. Ruth hit Hoyt hard, batting .563 with nine hits in 16 at-bats, including four homers.

Ruth had less success against Pennock, a reed-thin 160-pounder nicknamed the Squire of Kennett Square after his hometown in Pennsylvania. Pennock proved the perfect complement to Hoyt, serving as the southpaw ace of the dynastic Yankees of the late 1920s. Pennock’s career began with the Athletics in 1912, and he teamed with Ruth on the Red Sox from 1915 to 1919 before rejoining him in New York from 1923 to 1933. Pennock closed his career in 1934 with the Red Sox and retired with a 241-162 mark and 3.60 ERA. Like Hoyt, Pennock was a clutch pitcher, posting a 5-0 record and a 1.95 ERA in World Series competition.

In 20 at-bats against Pennock, The Babe rapped five hits for a .250 batting average. He made the most of those hits, four of them going for homers and the fifth one a triple. Ruth walked four times and fanned on three occasions.

Ruffing began his career in 1924 with the Red Sox and teamed with Ruth from 1930 to 1934. His peak years came during the second Yankees dynasty when he won 20 or more games in four straight seasons, 1936-39. He won 273 games in his career, lost 225 and owned an ERA of 3.80.

Ruffing was 7-2 in World Series competition, and Ruth had middling success against the right-hander, hitting .255 with 13 hits in 51 at-bats. He homered three times, drew 11 walks and struck out eight times.

Lyons, whose moniker was Sunday Teddy, enjoyed a 21-year career with the White Sox. From 1923 to 1946 he went 260-230 and fashioned a 3.67 ERA. Lyons won 21 or more games three times and led the league in victories in 1925 and ’27. He had less success against Ruth, The Bambino leaving Sunday Teddy with Monday morning blues. In 131 at-bats, Ruth reached the right-hander for 39 hits and seven homers. He doubled five times and tripled twice. Ruth drew 27 walks off Lyons and struck out 17 times.

Ruth’s most anticipated and most celebrated matchups may have been with Johnson, the feared and revered Big Train. Renowned for his “radio fastball” – hitters could hear it, couldn’t see it – Johnson won 417 games in a 21-year career with the Washington Senators. The Big Train’s career numbers are legendary – 12 campaigns with at least 20 wins, including 10 straight from 1910 to 1919. He won 33 games in 1912 and followed with a career-high 36 the following season.

The Babe and Big Train collided in 113 official at-bats. Ruth reached Johnson for 33 hits and a .292 batting average. He slugged eight homers and added eight doubles and two triples. The Big Train blew 25 third strikes past The Bambino.

Baseball’s All-Star Game didn’t begin until 1933, and Ruth, in the twilight of his career, played in only the first two midsummer classics. He made two plate appearances against Hubbell in 1934. The first began the famous string of strikeouts that saw Hubbell’s screwball fan future Hall of Famers Ruth, Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Al Simmons, and Joe Cronin in succession. The Bambino batted against King Carl again in the third inning and walked.

After Ruth changed leagues in 1935, he faced Hubbell in regular-season play. On April 16 at Braves Field, Ruth roped an RBI single to right field in the first inning and a two-run home run to right in the fifth to fuel a 4-2 victory. The Babe also struck out to end the second inning. Ruth’s homer off Hubbell was his final at-bat against the New York Giants’ southpaw. In five plate appearances against Hubbell, who was 253-154 lifetime with a 2.98 ERA, Ruth recorded one homer, a single, walk, and struck out twice.

Until 1969, baseball’s postseason consisted of the American and National League champions meeting in the World Series. Ruth’s postseason plate appearances against Hall of Famers were limited to facing Alexander, Grimes, and Haines. His first plate appearance against Alexander, a right-hander with a career mark of 373-208 and an ERA of 2.56, came in the ninth inning of Game One of the 1915 World Series.

Ruth, a member of the Red Sox, pinch-hit against Alexander, the Phillies ace who was working on a complete-game victory in Philadelphia’s Baker Bowl. Ruth grounded to first for the next to last out of the game. The 3-1 win was the lone victory for the Phillies, who fell to the Red Sox in five games.

Ruth and Alexander renewed acquaintances in Game Two of the 1926 World Series. Ruth was a Yankee by now, Alexander a Cardinal. The Babe went 0-for-4 in a 6-2 St. Louis victory. Ruth was completely handcuffed by the 39-year-old, striking out to end the first inning and failing to get the ball out of the infield the entire afternoon. In Game Six Ruth was 0-for-3 with a walk as Old Pete again went the distance, this time in a 10-2 win. Game Seven saw four future Hall of Famers climb the hill as Haines and Alexander threw for the Cardinals and Hoyt and Pennock for the Yankees. Old Pete trudged out of the bullpen in the seventh and didn’t face Ruth until the bottom of the ninth. The Babe worked a two-out walk but was thrown out trying to steal second with Bob Meusel at bat and Lou Gehrig on deck. The caught-stealing ended the game, 3-2, and gave St. Louis the championship.

Ruth also matched up with Haines in three games in the ’26 fall classic. A right-hander with a lifetime mark of 210-158 and an ERA of 3.64, Haines hurled the eighth inning in relief in Game One in Yankee Stadium and retired Ruth on a groundout to third. Haines started Game Three in St. Louis and went the route in a 4-0 win. He held The Babe to a 1-for-3 afternoon with a walk. Ruth’s lone hit was a single to shallow center to start the fourth. In Game Seven, at Yankee Stadium, Ruth homered off Haines to right-center field in the third inning to give New York a 1-0 lead. Otherwise, he drew four walks off Haines, one intentional.

Two years later, Ruth faced Alexander and Haines in a World Series with a much different ending. Alexander started Game Two in New York, and Ruth walked and scored in the first and singled and scored in the third to help key a 9-3 romp. Haines worked Game Three in St. Louis, and Ruth went 2-for-4 with two singles and two runs scored in a 7-3 victory. Alexander pitched in relief in the fourth and final game. The Babe, in his lone at-bat against Old Pete on that day, helped complete the sweep with a homer to right in the eighth, his record-setting third round-tripper of the afternoon.

Grimes, a stocky right-hander, spent 19 years in the majors with seven teams and compiled a 270-212 record with a 3.53 ERA.

Ruth’s appearances against Grimes came in the 1932 World Series, made famous by The Babe’s controversial “called shot.” Grimes pitched 1⅔ innings of relief in Game One in Yankee Stadium, and Ruth worked a walk to ignite a three-run inning that led to a 12-6 Yankees victory. Grimes didn’t pitch again until the ninth inning of the fourth and final game, and he got The Babe to ground out to first.

Baseball was segregated until 1947, so Ruth never faced the great black pitchers of his era in an official game. Ruth was quoted in the Pittsburgh Courier in August 1933 as endorsing the quality and showmanship of black players, and he encouraged white fans to watch the “kind of ball that colored performers play.” Negro League stars Judy Johnson, Cool Papa Bell, Buck O’Neil, Double Duty Radcliffe, Ray Dandridge, Buck Leonard, Willie Wells, and Monte Irvin returned Ruth’s high praise.3 “We could never seem to get him out no matter what we did,” Johnson told baseball historian Bill Jenkinson.4

Ruth played in numerous exhibition games against great Cuban and Negro League athletes, but many of the results are lost to history. In 16 documented games in which he faced Negro League pitchers, Babe batted .463, going 25-for-54 with 11 home runs. One such performance came in Trenton, New Jersey, one week after the Yankees swept Pittsburgh in the 1927 World Series. Facing aging fastball legend Dick “Cannonball” Redding, a pitcher some old-timers insisted was greater than Paige, Ruth ripped three consecutive tape-measure home runs.5

The story has layers. Trenton promoter George Glasco took Redding aside before the game and reminded him that the fans were there to see Ruth hit home runs, The Babe having smote a record 60 that season. Redding replied that he would heave his pitches “right down the pike.” Along with his three homers that day, Ruth also flied out and popped out.6

Ruth and Redding were not strangers to each other. They met in the fall of 1920, Babe homering off the Cannonball in a 9-4 loss. In the fall of 1925, Ruth and Redding squared off again. Redding and his Brooklyn Royals led by one run, but Ruth’s semipro squad put a runner on in the ninth. With Babe due to bat, Redding’s teammates had two words of advice for their pitcher: “Walk Ruth.” Redding instead tried to slip his fastball past The Bambino. Royals second baseman Dick Seay said Ruth swung his tree trunk of a bat and launched the Cannonball’s offering “into the next county.” In the fall of 1926, The Babe batted against Redding once more and stroked three hits, including two doubles, and struck out once in a 3-1 loss.7

Whether Ruth ever stepped to the plate against Paige is subject to question. Satchel said several times that he regretted never having pitched to Ruth, whom he referred to as the “big man.”8 Ruth’s daughter Julia Ruth Stevens, however, recalled an exhibition game in Brooklyn in which she said Paige got the better of her father. An oft-repeated rumor has Ruth fanning four times against Paige; whether that means in one game or lifetime has never been determined. Buck O’Neil remembered a different outcome during a barnstorming game in Chicago in the late 1930s. He said The Big Bam – as Ruth was sometimes called – hooked his bat into a Paige pitch and pounded a monstrous home run into the trees beyond the center-field wall. The home run was so prodigious – O’Neil estimated it flew 500 feet – that Satchel is said to have stared at The Bambino in wonderment as Ruth rounded the bases.9 According to the story, Paige was so impressed by Ruth’s power that he stood at home plate to shake The Babe’s hand. Satchel sent a boy to retrieve the ball so The Bambino could sign it. Whether the Ruth-Paige stories are fact or fiction depends on what one chooses to believe.

What is fact is that Ruth’s career marks against Hall of Fame pitchers are exceptional. He went 214-for-632, which translates to a .339 average. Add to that 47 home runs, 149 walks, and 140 strikeouts. Those numbers are strikingly close to his regular-season career averages: .342 batting average, 46 homers, 133 walks, and 86 strikeouts.

What this shows is that even against the greatest pitchers of his generation, Babe Ruth remained the King of Swing.

ED GRUVER is the author of seven books and a contributing writer to SABR’s Games Project and several online sports sites.

Notes

1 baberuth.com, Babe Ruth Quotes.

2 Ibid.

3 Bill Jenkinson, “Babe Ruth and the Issue of Race,” baberuthcentral.com.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 John Holway, “The Cannonball,” Society for American Baseball Research, Baseball Research Journal, 1980. https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-cannonball/

7 Ibid.

8 Satchel Paige and John B. Holway, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (Lincoln: Bison Books, 1993), 57.

9 Jenkinson.