Introduction: The Whiz Kids Take the Pennant

This article was written by C. Paul Rogers III

This article was published in 1950 Philadelphia Phillies essays

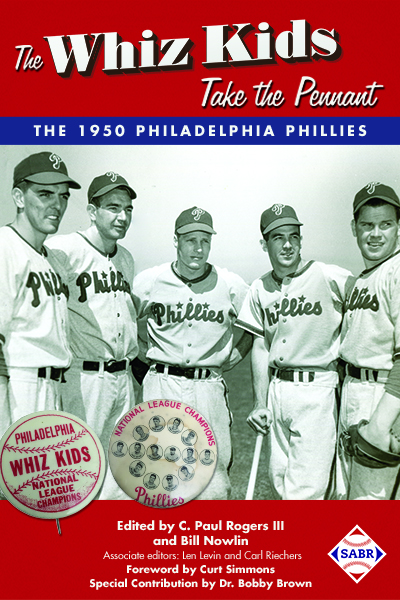

No one would seriously argue that the 1950 Philadelphia Phillies were one of the best teams in baseball history, but they certainly are one of the most memorable. Dubbed “the Whiz Kids” by sportswriter Harry Paxton because of their relative youth, they proved to be most resilient and able to overcome adversity. Although they threatened to run away with the pennant during the dog days of late summer, injuries, the loss of fireballing southpaw Curt Simmons to active military duty, and a late-season hitting slump almost cost them the pennant, where they would have forever been remembered as the Fizz Kids. But the story has a happy ending (excluding the World Series) because the Phillies managed to beat the Brooklyn Dodgers in a thrilling 10-inning game on the last day of the season in Ebbets Field to win the pennant.

No one would seriously argue that the 1950 Philadelphia Phillies were one of the best teams in baseball history, but they certainly are one of the most memorable. Dubbed “the Whiz Kids” by sportswriter Harry Paxton because of their relative youth, they proved to be most resilient and able to overcome adversity. Although they threatened to run away with the pennant during the dog days of late summer, injuries, the loss of fireballing southpaw Curt Simmons to active military duty, and a late-season hitting slump almost cost them the pennant, where they would have forever been remembered as the Fizz Kids. But the story has a happy ending (excluding the World Series) because the Phillies managed to beat the Brooklyn Dodgers in a thrilling 10-inning game on the last day of the season in Ebbets Field to win the pennant.

It was the only the second pennant in Phillies history and the first in 35 years. The Phillies’ run to the flag was marked by clutch hitting and pitching in close games; in fact, they won 29 of 45 one-run games during the regular season. Along the way, the young team captured the attention of not only of victory-starved Philadelphia but indeed of the entire nation, including 10-year-old Bobby Knight growing up in Ohio. Some 60 years later Coach Knight could still name the Whiz Kids’ starting lineup.1

Between the two pennants, the Phillies were mostly dreadful, finishing in the first division only once between 1917 and 1949. They finished dead last 16 times between 1919 and 1945, including five straight years from 1938 to 1942, once finishing 28½ games out of seventh place. The club was plagued by so-called “five and dime” owners who had little financial resources and ran the club on a shoestring. It was common practice for the team to sell star players, such as Grover Cleveland Alexander and later Lefty O’Doul, Chuck Klein, Dolph Camilli, and Kirby Higbe for cash to keep the franchise afloat. Hugh Mulcahy, a fine pitcher who was the first major leaguer drafted in anticipation of World War II, lost so many games that he earned the nickname in the press of “Losing Pitcher” because his name appeared as the losing pitcher in the box score so often.

Until 1938 the club played in an awful bandbox called the Baker Bowl, which sported a right-field wall only 280 feet from home plate, 35 feet high and made of tin. One pitcher, Walter Beck, earned the nickname “Boom Boom” from pitching in the Baker Bowl: one boom when the ball hit the bat, the other when it hit the tin wall. For much of the 1930s a large billboard adorned the tin wall advertising Lifebuoy Soap. The sign proudly proclaimed that “The Phillies Use Lifebuoy,” underneath which a disgruntled fan scrawled one night, “And They Still Stink.”

In 1943 the National League was forced to take over the franchise from owner Gerald Nugent, who could no longer pay his bills. The league sold the team to 33-year-old William Cox, a New York lumber executive. He didn’t last long, kicked out of the game in November by Commissioner Kenesaw Landis for betting on the Phillies. Apparently he bet only on the team to win, but that lapse in betting judgment did not save him.2 Robert R.M. Carpenter Sr. was next up, purchasing the team for his son, Robert R.M. Carpenter Jr., to run. Young Bob was only 28 years old, but had played football at Duke for Wallace Wade and loved sports.

The sale of the team to the Carpenters was the turning point. The elder Carpenter was married to a DuPont and so finally the club had an owner with financial resources. They embarked upon a five-year plan to rebuild the team from the ground up and first named Herb Pennock, who had won 241 games in a Hall of Fame pitching career, as general manager. In fact, Pennock was the first real general manager in Phillies history. The club then went about signing the best young talent coming out of high school and college. They outbid 15 other teams to sign Curt Simmons to a record $65,000 bonus, even going so far as to send the major-league team to Simmons’ hometown of Egypt, Pennsylvania, to play an exhibition game in which Simmons pitched for the town team against the Phillies.3

The Carpenters also paid sizable bonuses to Robin Roberts out of Michigan State, as well as Richie Ashburn, Del Ennis, Stan Lopata, Putsy Caballero, Granny Hamner, Willie Jones, Bubba Church, and Bob Miller, all of whom were future Whiz Kids. On the field, the Phillies gradually improved as more and more of the talented youngsters were called up to the big-league club. In midseason 1948 Bob Carpenter fired the acerbic Ben Chapman as manager and replaced him with Eddie Sawyer, a career minor leaguer who had never played or managed in the major leagues. Sawyer had managed several future Whiz Kids in Utica, New York, and proved to be the perfect choice to lead the young team. He believed in keeping the game simple by just letting talented players play to get the most out of their abilities.

Success was not immediate but was not far off. The team floundered the last half of 1948 and finished sixth, 22 games under .500, as Sawyer replaced veterans with the youngsters. Pennock had unfortunately died suddenly in January 1948 but the younger Carpenter felt ready to take over the baseball operations and added some valuable players in trades, including Dick Sisler from the Cardinals, and Eddie Waitkus, Russ Meyer, and Bill Nicholson from the Cubs. Sawyer also brought up the veteran Jim Konstanty, whom he had managed in Toronto, to shore up the bullpen.

In 1949 the team was much improved, and on June 2 tied a major-league record by slugging five home runs in one inning, two by veteran catcher Andy Seminick, against the Cincinnati Reds in Shibe Park.4 The team managed to weather the near-fatal shooting of first baseman Eddie Waitkus by a deranged female admirer later that month. After an August slump, the team won 27 of its final 43 games to finish in third place with an 81-73 record. After the final game of the season Sawyer gathered his team in the clubhouse and told them, “Come back next year ready to win the pennant.”

The Phillies were able to do just that in 1950, if just barely in a pennant race that went down to the final day of the season. The club played only .500 ball in April but then got rolling behind a young starting rotation consisting of Simmons, who after two inconsistent years hit his stride, Roberts, who also had a breakout season, and two rookies, Bob Miller and Bubba Church. Waitkus had returned at first base from his life-threatening gunshot wound while “Grandpa Whiz,” 29-year-old veteran catcher Seminick, was having a career year at bat while masterfully handling the young pitching staff. The 33-year-old Konstanty, buoyed by his private undertaker pitching coach, was so dominant out of the bullpen that he would win the National League’s Most Valuable Player Award.

The Whiz Kids took over first place for good in early July. They had a five-game lead by August 12 and, fueled by a memorable brawl against the New York Giants when Seminick took out most of the Giants infield, won 14 out of 18. By the middle of September the Phillies had stretched their lead to 7½ games, even with the loss of Simmons to active duty. But injuries to Miller and Church, who was felled by a line drive to the face off the bat of Ted Kluszewski, the hospitalization of veteran pinch-hitter Nicholson because of diabetes and a team hitting slump reduced their lead to a single game over the powerful Brooklyn Dodgers heading into the final game of the season against those Dodgers in Ebbets Field. The Whiz Kids had lost five in a row and eight of 10 heading into that last game. If they lost, it meant a three-game playoff against Brooklyn, which did not bode well for the pitching-thin Phillies.

But they did not lose, winning a thrilling 10-inning game behind workhorse Roberts, who was starting for the third time in five days. They did, however, come about as close to losing as a team can. In the bottom of the ninth in a tie game, the Dodgers had runners on first and second with no outs when Duke Snider laced a line drive hit to center field. Richie Ashburn, who supposedly had a weak throwing arm, scooped the ball on one hop and threw out Cal Abrams, the potential winning run, at the plate by 15 feet.

The Dodgers now had runners on second and third with only one out, but, after intentionally walking Jackie Robinson to load the bases, Roberts bore down and retired Carl Furillo on a foul popup to Waitkus for the second out. Gil Hodges was next and he lifted a fly ball to right field. It looked like a can of corn to the fans, but Del Ennis lost the ball in the late-afternoon sun as the ball descended. It hit Ennis in the chest and fortuitously dropped into his glove for the third out, allowing the Phillies to escape the inning. After the game, Ennis had stitch marks from the ball on his chest.

In the top of the 10th inning, the Phillies managed to get runners on first and second with one out to bring Dick Sisler to the plate against Dodgers ace Don Newcombe. On a one-ball, two-strike pitch, Sisler hit the most dramatic home run in Phillies history with an opposite-field line drive into the left-field stands to give the Whiz Kids a 5-2 lead. Roberts retired the Dodgers in order in the bottom of the inning, giving the Phillies the pennant and bringing a huge sigh of relief from all of Philadelphia.

The World Series against the New York Yankees was a little anticlimactic, at least from the Phillies’ perspective, and without Curt Simmons they went down to defeat in four games, the first three of which were tense, tight one-run pitching duels. While the Whiz Kids were disappointed about the Series, they thought they would have other chances to be World Series champions. It was not to be, however. Players like Konstanty, Seminick, and Sisler were unable to repeat their career years and Simmons was still on active duty in 1951 as the team slipped to fifth place. The Phillies’ refusal to integrate further hampered their ability to compete for future pennants.5 The 1950 team remains the last all-white team to win the National League pennant, a record that is in no jeopardy of being broken.

This book tells the story of those Whiz Kids, a team with one of the most memorable nicknames in baseball history.6 It contains biographies of every player who appeared in a game plus game stories of important games, and many other features about this unique team. In addition to a Foreword by Whiz Kid Curt Simmons, it even contains a “View From the Other Side” by Yankees third baseman and former American League President Dr. Bobby Brown. It is the product of the dedicated, uncompensated work of 36 members of the Society for American Baseball Research, all of whom share a love of baseball and its rich history. Even for the most knowledgeable baseball fan, what follows is a treasure trove of fascinating anecdotes and facts about a bygone era of baseball when the uniforms were flannel, the players still left their gloves on the field between innings, and the games were played in two hours.

PAUL ROGERS is co-author of several baseball books including The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Temple University Press, 1996) with boyhood hero Robin Roberts, and Lucky Me: My 65 Years in Baseball (SMU Press 2011) with Eddie Robinson. Paul is president of the Ernie Banks – Bobby Bragan DFW Chapter of SABR and a frequent contributor to the SABR BioProject, but his real job is as a law professor at Southern Methodist University, where he served as dean of the law school for nine years. He has also served as SMU’s faculty athletic representative for 30 years.

- Read more: Click here to download the free e-book edition or save 50% off the purchase of the paperback from the SABR Digital Library.

- Player bios: Find 1950 Phillies biographies at the SABR BioProject.

- Game recaps: Find memorable 1950 Phillies game stories at the SABR Games Project.

Notes

1 Many serious baseball fans from that era get stumped on Mike Goliat, the Whiz Kids second baseman, when trying to recall the Phillies starting lineup, since Goliat played only that one full year in the big leagues.

2 The 1943 Phillies finished in seventh place with a 64-90 record, 41 games out of first place.

3 Simmons almost defeated the Phillies but the game ended in a 4-4 tie after two town outfielders collided chasing a fly ball, allowing the Phillies to tie the score. The game was then called because of darkness. C. Paul Rogers III, “The Day the Phillies Went to Egypt,” Baseball Research Journal, Fall, 2010: 9-12.

4 C. Paul Rogers III, “The Day the Phillies Came of Age,” National Pastime, (1999): 31-33.

5 The Phillies did not sign their first black player until 1956. In the late 1940s, the Phillies reportedly refused to give Roy Campanella, who was from Philadelphia, even a chance to tryout. He went on to a Hall of Fame career with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

6 Most would agree that the Whiz Kids sobriquet rivals other team nicknames such as the Gas House Gang, the Bronx Bombers, the Miracle Braves, and the Big Red Machine as among most memorable in baseball history.