The Protection Myth: Most Pitchers Don’t Duck the Risk of 20 Losses

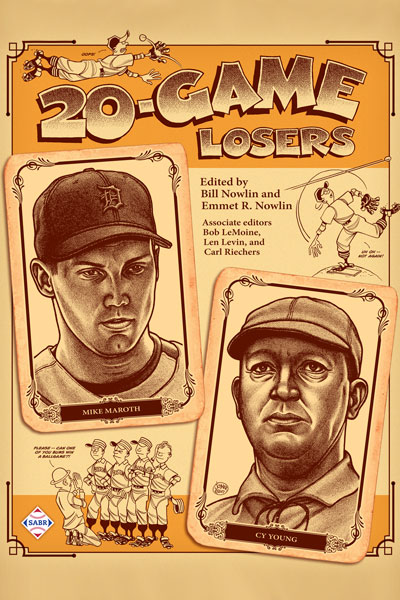

This article appears in SABR’s “20-Game Losers” (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Chris Archer took the mound for the Tampa Bay Rays at Chicago’s U.S. Cellular Field on September 29, 2016, in a meaningless game between two teams slogging to the end of disappointing seasons. But a defeat would make Archer the majors’ first 20-game loser in a dozen years.

Chris Archer took the mound for the Tampa Bay Rays at Chicago’s U.S. Cellular Field on September 29, 2016, in a meaningless game between two teams slogging to the end of disappointing seasons. But a defeat would make Archer the majors’ first 20-game loser in a dozen years.

That didn’t matter to him – or so he said. He didn’t believe a pitcher’s won-lost record was a true measure of his value. The 28-year-old right-hander was a rising star suffering through a miserable season. Personable and outgoing, he was a fan and media favorite, and a tireless off-the-field worker on behalf of children.

The first half of 2016 had been a disaster. After the Rays’ ace lost his first four games, his ERA stood at 7.32 and the sports talkers were asking, “What’s wrong with Archer?” He had turned it around, holding opposing batters to a .260 on-base percentage after the All-Star break.

Archer’s 19th defeat came on September 23 when Boston beat him, the 11th straight time he had lost to the Red Sox. The score, 2-1, was typical of his season; the last-place Rays had scored no more than two runs in 12 of his losses.

In his final start he shut out the White Sox until the sixth, and his teammates gave him a 5-1 lead at the seventh-inning stretch. In the bottom of the seventh, Chicago’s light-hitting second baseman, Carlos Sanchez, slammed a two-run homer to narrow the margin to 5-3. That was also typical of Archer’s season; it was the 30th home run he had allowed. Relievers Brad Boxberger, Erasmo Ramirez, and Alex Colome pitched scoreless ball the rest of the way to preserve the victory, only Archer’s ninth of the year.

He insisted he hadn’t worried about a 20th loss: “Honestly, I never let those type of things creep into my mind because it’s pointless to think about negatives.”1

Tampa Bay Times columnist Martin Kennelly said that if he had been Archer, “I would have come up with a stomach flu or something, anything.”2 The comment reflects the widespread belief that pitchers will hide in their lockers to avoid the stigma of a 20-loss season.

It ain’t so, Joe. It is not at all common for a pitcher to dodge the risk of a 20th defeat. In 56 seasons of baseball’s Expansion Era, since 1961, pitchers have lost 19 games 67 times (some more than once). The majority, 39, took their chances in at least one more start. For most it was a bad, if brave, bet; 31 of them were charged with a 20th defeat.

Two days after Archer’s last start of 2016, the White Sox’ James Shields lost his 19th decision. It came in Chicago’s 161st game, so Shields didn’t pitch again. That was the case with 15 of the pitchers who have lost 19 games in the Expansion Era: The season ended before they had a chance to lose number 20.

Just 13 of the 67 19-game losers were protected from a 20th defeat by either their managers or their own choice. Here are three typical examples:

In 2003 Detroit’s Jeremy Bonderman lost his 19th in the club’s 153rd game. His teammate Mike Maroth had already lost 21 as the Tigers staggered to the worst record in their history, 43-119.

Manager Alan Trammell was protecting Bonderman, a 20-year-old rookie right-hander who was one of the Tigers’ bright hopes for the future. He had been dropped from the starting rotation in September because he was getting battered; he finished with a 5.56 ERA. After his 19th defeat in his only start in the last four weeks of the season, Bonderman said, “I don’t care what happens, I just want to play.”3 Trammell put him into two more games as a reliever, in situations when the Tigers had big leads so he wasn’t at risk of being charged with a loss.

In some cases managers made it clear that they didn’t want their man to lose again. When the Cardinals’ Jose DeLeon was knocked out in the second inning of his 19th defeat in 1990, his catcher, Tom Pagnozzi, said, “Not only was it not a good day, but it was not a good year.” It was DeLeon’s 14th loss in his last 15 decisions. What’s more, he had suffered through a 2-19 season with Pittsburgh five years earlier.

Cardinals manager Joe Torre said DeLeon’s confidence was shot: “He has to start over and not even know this year existed.”4 As it happened, DeLeon developed arm trouble the following year and was never a frontline starter again.

Some pitchers quietly disappeared after a 19th defeat. In 1990 Tim Leary lost his 19th in the Yankees’ 149th game and didn’t pitch again. Leary didn’t deserve his 9-19 record; his adjusted ERA of 96 was just slightly worse than league-average. The club was in last place, going nowhere but home. The Yankees made no announcement, but they were negotiating a new contract with Leary and evidently decided to save him from embarrassment.

Only seven other Expansion Era pitchers have done what Archer did. Like Ted Williams chasing a .400 batting average on the last day of the 1941 season, they chose to face failure and stared it down. They avoided the dreaded 20th loss.

In 1993 Minnesota’s Scott Erickson lost his 19th, his fourth straight defeat, in the club’s 149th game. Taking his regular turn, Erickson started twice more. He didn’t discuss his decision; he wasn’t speaking to the media. A “mystery man” who dressed in black but couldn’t sing like Johnny Cash, the right-handed sinkerballer had been a 20-game winner during the Twins’ worst-to-first run in 1991, but had fallen on hard times.

His next start almost became his 20th loss. After he left the game in the seventh with two men on, reliever Carl Willis allowed both to score, putting Boston up, 4-3, with Erickson in line to be the losing pitcher. The Twins rallied to tie, taking him off the hook. In his final appearance he worked seven innings against the Angels and sat down with a 2-1 lead. Again Twins relievers blew the lead and the game, leaving Erickson with no decision. He finished 8-19 with a 5.19 ERA.

Right-hander Mike Moore spent the first seven years of his career with the 1980s Seattle Mariners, so he had plenty of losing experience. In 1987 he lost for the 19th time on September 20, in the Mariners’ 149th game. He started twice more and won them both, although he gave up six earned runs in his final start, to finish at 9-19. Two years later Moore was traded to Oakland, won 19 games, and wound up pitching in two World Series with the A’s.

Oakland’s Vida Blue, a three-time 20-game winner, lost his 19th in the Athletics’ 152nd game of 1977. With the club headed for last place in the AL West, he took his next turn and pitched nine innings without a decision. “I was glad not to lose 20, but it’s no big deal,” he said.5 He skipped his final start, pleading a tired arm after 279⅔ innings. Blue was traded to the Giants after the season; he would happily have swum across the bay to get away from the sinking, stinking A’s.

Frank Tanana was the rookie phenom of 1974 when he joined the Angels’ rotation. (He had started four games the previous September.) But he lost seven straight decisions in June and July to fall to 4-13 with a 4.05 ERA.

After the All-Star break the 20-year-old left-hander looked like a different pitcher. “I said to myself, ‘Hey, if I don’t turn myself around I’m going to [Triple-A] Salt Lake City,’” he explained. “I buckled down.”6 He began missing bats and dramatically cut down his walks and home runs allowed.

The Angels were no help; they settled at the bottom of the AL West. Despite a 2.13 ERA in the second half, Tanana was charged with his 19th loss in Game 155. “He’s going to be a damn good pitcher,” manager Dick Williams said. “We wouldn’t care if he had 10 more shots at losing that 20th.”7 Tanana made two more starts, both complete-game victories. He beat Minnesota, 3-2, and then, with three days’ rest, shut out first-place Oakland, striking out 10. The Sporting News named the 19-game loser the AL Rookie Pitcher of the Year.

Tanana’s September promotion a year earlier probably saved teammate Clyde Wright from 20 losses. When Wright lost for the 17th time in 1973, a little girl named Debbie Wright, not related, gave him a rabbit’s foot. He won his next two games, but the rabbit’s good luck soon died. Clyde (and Debbie) were victims of weak run support; the Angels scored no more than two runs in 13 of his starts.

After the veteran lefty lost his 19th in Game 135, with nearly a month left in the season, Tanana replaced him in the rotation as the team tried out some prospects. Wright pitched once in mop-up relief, then made two spot starts with a victory and a no-decision to finish at 11-19. The Angels traded him to Milwaukee, where he lost 20 the next year.

Unlike Tanana, Gaylord Perry was an established ace coming off a Cy Young Award when he lost 19 with Cleveland in 1973. He started 41 times that year and worked a career-high 344 innings for the last-place Indians. Perry’s 19th defeat came in Game 143. After that he took the ball every fourth day and won four in a row, the last a 1-0 shutout of Boston, to square his record at 19-19. Perry’s turn came around again on the final day of the season. He could have finished as a 20-game winner or a 20-game loser. Instead he went home to North Carolina, saying in effect, “Who cares?”

Twenty-four-year-old Steve Carlton had blossomed into an elite pitcher in 1969, when his 2.17 ERA was second in the National League. But in 1970 his ERA ballooned by 1.56 runs and his strikeout rate declined on the way to 19 defeats. “My control hasn’t been as good and I haven’t been getting my pitches down as well as last year,” he said.8 (He had not yet stopped talking to reporters.)

After losing number 19 in the Cardinals’ 148th game, Carlton didn’t run away. He started twice more, pitching seven innings without a decision and then ending his season with a complete-game victory over Montreal.

To recap:

19-Game Losers, 1961-2016

|

Made at least one more start |

39 |

|

Season ended before next start |

15 |

|

“Protected” from 20 losses |

13 |

These findings show that the round number 20 in the loss column is a bigger deal for sportswriters and fans than for pitchers. Major-league pitchers are competitive men. Most don’t want to be seen as quitting on the team or playing for their own statistics.

So when another pitcher loses number 19, watch what he does next.

WARREN CORBETT is the author of The Wizard of Waxahachie: Paul Richards and the End of Baseball as We Knew It, and a contributor to SABR’s BioProject.

Sources

Statistics from Baseball-reference.com and its Play Index.

Notes

1 Mark Topkin, “Rays’ Archer Tops 200 Innings, Avoids 20 Losses in Win Over White Sox,” Tampa Bay Times, September 29, 2016. tampabay.com/sports/baseball/rays/rays-manager-cash-says-record-wont-define-archer/2295899, accessed November 8, 2016.

2 Martin Fennelly, “Rays’ Chris Archer, the 20-Loss Stigma and The Measure of This Pitcher,” Tampa Bay Times, September 29, 2016. tampabay.com/sports/baseball/rays/rays-chris-archer-the-20-loss-stigma-and-the-measure-of-this-pitcher/2295755, accessed November 8, 2016.

3 Associated Press, “Twins Maintain AL Central Lead,” Fort Myers (Florida) News-Press, September 20, 2003: 31.

4 Rick Hummel, “Torre Looking for Changes in DeLeon in 1991,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 29, 1990: 4C.

5 “Vida Happy It’s Over,” San Mateo (California) Times, September 29, 1977: 19.

6 Dick Miller, “Brash Tanana Wins Frosh Hill Prize,” The Sporting News, November 26, 1974: 44.

7 Dan Hafner, “Angels Win 3-2 on Pinch Single,” Los Angeles Times, September 28, 1974: III-5.

8 Associated Press, “Major Leagues,” Chillicothe (Missouri) Constitution-Tribune, September 9, 1970: 21.

19-Game Losers, 1961-2016

Compiled by Carl Riechers and Warren Corbett

Source: baseball-reference.com

Protected

Total: 13. These pitchers did not start again after their 19th defeat, skipping at least one turn.

- 1961: Art Mahaffey, Phillies, record 11-19.

- 1961: Bob Friend, Pirates, 14-19.

- 1962: Jay Hook, Mets, 8-19.

- 1963: Don Rudolph, Senators, 7-19.

- 1974: Paul Splittorff, Royals, 13-19.

- 1974: Jim Bibby, Rangers, 19-19.

- 1974: Wilbur Wood, White Sox, 20-19.

- 1978: Rick Wise, Indians, 9-19.

- 1990: Tim Leary, Yankees, 9-19.

- 1991: Kirk McCaskill, Angels, 10-19.

- 2000: Omar Daal, Diamondbacks-Phillies, 4-19.

- 2003: Jeremy Bonderman, Tigers, 6-19.

- 2004: Darrell May, Royals, 9-19.

Not Protected

Total: 39. These pitchers made one or more additional starts after their 19th defeat.

- 1961: Pedro Ramos, Twins, 11-20.

- 1962: Roger Craig, Mets, 10-24.

- 1962: Al Jackson, Mets, 8-20.

- 1962: Dick Ellsworth, Cubs, 9-20.

- 1962: Turk Farrell, Astros, 10-20.

- 1963: Roger Craig, Mets, 5-22.

- 1963: Orlando Pena, Athletics, 12-20.

- 1964: Tracy Stallard, Mets, 10-20.

- 1964: Jack Fisher, Mets, 8-24.

- 1965: Larry Jackson, Cubs, 14-21.

- 1965: Al Jackson, Mets, 8-20.

- 1966: Dick Ellsworth, Cubs, 8-22.

- 1966: Mel Stottlemyre, Yankees, 12-20.

- 1969: Clay Kirby, Padres, 7-20.

- 1969: Luis Tiant, Indians, 9-20.

- 1970: Steve Carlton, Cardinals, 10-19.

- 1971: Denny McLain, Senators, 10-22.

- 1972: Steve Arlin, Padres, 9-19.

- 1973: Stan Bahnsen, White Sox, 18-21.

- 1973: Steve Carlton, Phillies, 13-20.

- 1973: Wilbur Wood, White Sox, 24-20.

- 1973: Clyde Wright, Angels, 11-19.

- 1973: Gaylord Perry, Indians, 19-19.

- 1974: Bill Bonham, Cubs, 11-22.

- 1974: Randy Jones, Padres, 8-22.

- 1974: Steve Rogers, Expos, 15-22.

- 1974: Mickey Lolich, Tigers, 16-21.

- 1974: Clyde Wright, Brewers, 9-20.

- 1974: Frank Tanana, Angels, 14-19.

- 1975: Wilbur Wood, White Sox, 16-20.

- 1977: Jerry Koosman, Mets, 8-20.

- 1977: Phil Niekro, Braves, 16-20.

- 1977: Vida Blue, Athletics, 14-19.

- 1979: Phil Niekro, Braves, 21-20.

- 1980: Brian Kingman, Athletics, 8-20.

- 1987: Mike Moore, Mariners, 9-19.

- 1993: Scott Erickson, Twins, 8-19.

- 2003: Mike Maroth, Tigers, 9-21.

- 2016: Chris Archer, Rays, 9-19.

Season ended before next start

Total: 15.

- 1964: Galen Cisco, Mets, 6-19.

- 1966: Sammy Ellis, Reds, 12-19.

- 1967: George Brunet, Angels, 11-19.

- 1969: Bill Stoneman, Expos, 11-19.

- 1970: Mickey Lolich, Tigers, 14-19.

- 1971: Steve Arlin, Padres, 9-19.

- 1974: Bill Greif, Padres, 9-19.

- 1974: Lerrin LaGrow, Tigers, 8-19.

- 1977: Wayne Garland, Indians, 13-19.

- 1985: Jose DeLeon, Pirates, 2-19.

- 1985: Matt Young, Mariners, 12-19.

- 1990: Jose DeLeon, Cardinals, 7-19.

- 2001: Albie Lopez, Devil Rays-Diamondbacks, 9-19.

- 2001: Bobby J. Jones, Padres, 8-19.

- 2016: James Shields, Padres-White Sox, 6-19.