Beyond Bunning and Short Rest: An Analysis of Managerial Decisions That Led to the Phillies’ Epic Collapse of 1964

This article was written by Bryan Soderholm-Difatte

This article was published in Fall 2010 Baseball Research Journal

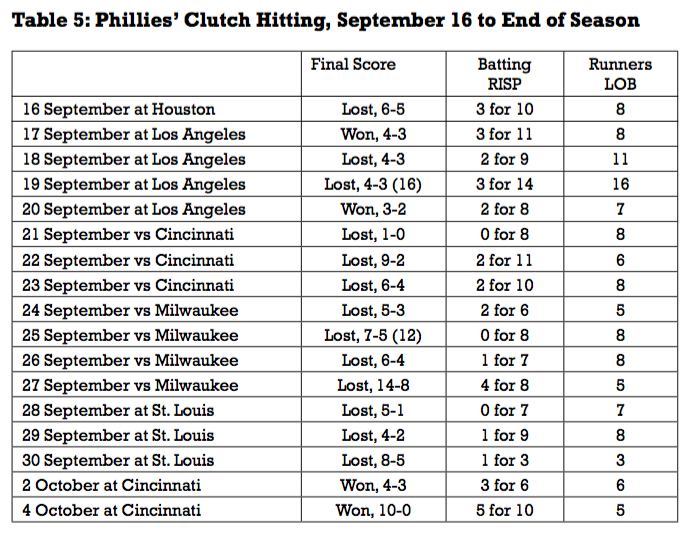

Nearly all accounts of the 1964 Philadelphia Phillies’ epic collapse, which would etch itself deep in the city’s historical psyche, focus on the Phillies’ 10-game losing streak that started on September 21, when they had a 6½-game lead with only 12 games remaining, and ended with them having lost eight games in the standings in ten days. Half of the Phillies’ preferred starting rotation was grappling with injuries—Dennis Bennett was pitching with a sore shoulder, and Ray Culp had not pitched since mid-August because of arm trouble.

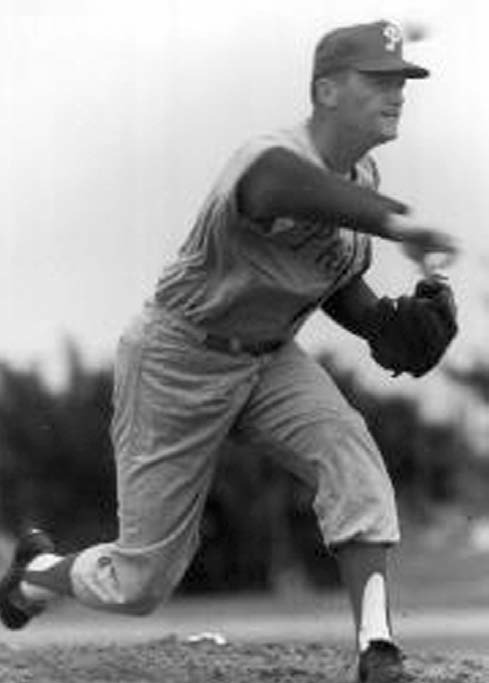

Even so, manager Gene Mauch is often blamed for starting his two best pitchers, right-handed ace Jim Bunning and left-handed ace Chris Short, twice each on two days’ rest, instead of the normal three, during the losing streak. In accounts of the Phillies’ implosion—by David Halberstam in October 1964 and William C. Kashatus in September Swoon: Richie Allen, the ’64 Phillies, and Racial Integration and in the Baseball Prospectus compilation on great pennant races, It Ain’t Over ’Til It’s Over — Mauch is portrayed as increasingly panicked, lashing out at his players and perhaps over-managing in a desperate attempt to salvage the pennant.1

These narratives provide an excellent account of what happened, including key plays along the way— such as with the ever dangerous Frank Robinson at bat, Reds utility infielder Chico Ruiz daringly steals home with two out in the sixth inning, scoring the only run in the game that began the Phillies’ 10-game losing streak—and players’ perspectives on the unfolding disaster. The authors of these accounts note that Mauch’s decision to start Bunning and Short on short rest was ill conceived and probably cost the Phillies some games they might have won had those two been pitching on normal rest. But they do not consider some other decisions made by Mauch that might have cost the Phillies some games during those critical weeks.

After a comprehensive play-by-play analysis from the game logs posted at Baseball-Reference and made available through the painstaking efforts of Retrosheet researchers, I believe there were at least six critical decisions Mauch made, other than those affecting how he used Bunning and Short in the final two weeks, that backfired to upend Philadelphia’s pennant dream. Four of them came in the five days before the Phillies began their 10-game losing streak. To make sure that I fully understood the circumstances of the games, I personally scored each play of each game so I could plainly see how each game developed.

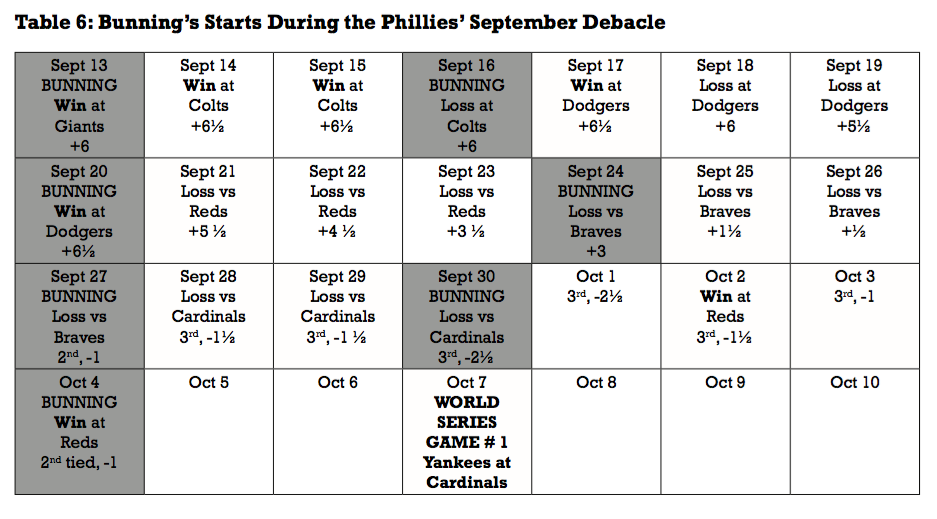

I started with the Phillies’ game at Houston on September 16. They went into this game with a comfortable lead of 6 games, with 17 left on the schedule. This was the first of three September starts that Bunning made on only two days’ rest. The other two are more understandable, because they’re in the midst of the Phillies’ 10-game losing streak. But why would manager Mauch start Bunning on short rest on September 16, when at this point the prospect for a tight pennant race down the stretch looked so unlikely? To understand the context, let’s begin with a quick look at how the Phillies got to where they were.

HOW THE PHILLIES GOT TO THE THRESHOLD OF A PENNANT

In the article on the 1964 pennant race in It Ain’t Over ’Til It’s Over, the argument is made that what is often overlooked in discussions of the Phillies’ collapse is that the team should not have been in contention in the first place, notwithstanding that they exceeded expectations by finishing surprisingly high, fourth place, in 1963.2 Mauch’s daily lineup was much less settled than that of the National League’s other putative contenders for 1964—the defending champion Dodgers; the Cardinals, who had finished second the previous year; the Reds; and the Giants—and with many more weaknesses. Mauch had only three players whose names he wrote into the lineup every day—Johnny Callison in right field, Tony Taylor at second base, and rookie sensation Richie Allen, as Dick Allen was then called (against his wishes) at third base. Callison and Allen both had sensational years; Taylor was a steady hand at best.

The only other position player to start as many as 100 games for the Phillies was catcher Clay Dalrymple, a left-handed batter who platooned with the right-handed Gus Triandos. Mauch started the season platooning the rookie left-handed-hitting John Herrnstein at first base with the veteran right-handed-hitting Roy Sievers. Neither hit well, and by mid-season Sievers was gone and replaced by veteran right-handed-hitting Frank Thomas (acquired from the Mets in early August), who took over the position full-time until suffering a hand injury in early September that kept him out of the lineup most of the final month of the season. Mauch used a platoon in left field, with the left-handed-hitting Wes Covington paired off first with rookie Danny Cater and later with rookie Alex Johnson, and in center field for most of the second half of the season, with the left-handed-hitting Tony Gonzalez trading off with Cookie Rojas. Mauch started the year with Bobby Wine as his regular shortstop and ended using mostly Ruben Amaro, neither of whom hit well.

Going into the season, the Phillies’ pitching was not considered on par with that of the other NL-contending teams. Only Jim Bunning, acquired in a winter trade from Detroit, had an established pedigree. Mauch’s starting rotation was right-handers Bunning and Ray Culp and southpaws Chris Short and Dennis Bennett as his core four, with righty Art Mahaffey as a fifth starter. Jack Baldschun was the best of an otherwise suspect bullpen. By September, however, Mauch’s starting rotation was in deep trouble. Culp was sidelined with an elbow problem and made his last start on August 15, and Bennett was battling a persistently sore shoulder. Bennett continued to pitch through the pain. Mauch replaced Culp in his fourman rotation with Mahaffey, and 18-year old rookie Rick Wise replaced Mahaffey as the fifth starter, whenever one was needed. Fortunately, Bunning and Short were healthy and pitching well.

The Phillies got off to a fast start, winning 9 of their first 11 games, and never trailed by more than 2 games as they positioned themselves for a pennant chase. On July 16, they moved into a tie for first and gradually built a lead that reached 7½ games on August 20 after a string of 12 wins in 16 games against the three worst teams in the league—the Cubs, the Colts, and the Mets. The Dodgers had imploded, getting off to a 2–9 start, and never recovered. The Giants had spent much of May and June in first place but then went 28–31 in July and August, reaching a nadir of 8½ games behind the Phillies on August 21, amid racial-diversity issues in the San Francisco clubhouse. The Reds had split their first 44 games (actually their first 45, as one was a tie) and then began a steady climb up the standings from sixth to second, which they reached on August 20, although settling in at a distant 7½ games behind the Phillies. And the Cardinals were languishing in eighth place with a 28–31 record on June 15 when they made the trade with the Cubs that brought them Lou Brock. The Cards still trailed by as many as 11 games on August 23, presumably not harboring pennant dreams, but won 13 of their next 16 games—the last in Philadelphia—to close within 5 games of the Phillies, in second place, on September 9.

By mid-September, the question of whether the Phillies were good enough to compete for the pennant was moot. Paced by Allen and Callison on the offensive side, and by Bunning and Short on the mound, Gene Mauch had his Phillies in command of the pennant race. To say that the Phillies had overachieved to get to this point—a 6-game lead with 17 games remaining after Bennett and Baldschun combined for a four-hit, 1–0 shutout in Houston on September 15—and that their subsequent collapse should somehow not diminish the great success they had in 1964 would be disingenuous. Some of the most compelling pennant races in baseball history have involved teams that were not expected to compete but did, and won—the 1914 “Miracle” Braves, the 1969 “Miracle” Mets, anyone?

Of course, some might argue that the 1964 Phillies peaked too early—that eventually their weaknesses caught up with them—while the 1914 Braves and 1969 Mets peaked at just the right time, both coming from far behind to finish first by a decisive margin, their late-season momentum carrying them on to win the World Series before their weaknesses could reassert themselves.

MAUCH’S MAJOR STRATEGIC BLUNDER—LOOKING AHEAD TO THE WORLD SERIES?

MAUCH’S MAJOR STRATEGIC BLUNDER—LOOKING AHEAD TO THE WORLD SERIES?

And so it was with great expectations that the good citizens of the City of Brotherly Love awoke on the morning of September 16, 1964, for their Phillies had beaten the Colts out in Houston the night before and held a commanding 6-game lead over second-place St. Louis, with time for the other contenders running out fast. San Francisco was 7½ games back, and Cincinnati, 8½. The Phillies, in fact, had been in first place every day since July 17. It seemed inconceivable that the Phillies would not soon be appearing in the World Series for the third time in franchise history.

It was then that Gene Mauch made perhaps his biggest mistake of the season. He decided to start Bunning, his ace, in Houston on September 16, on only two days’ rest. The ninth-place Colts were certainly not contenders. Moreover, in his last start, a 4–1 ten-inning complete game victory in San Francisco, he struck out nine and gave up seven hits. Pitch counts were not much (if at all) in managers’ minds back then and were not recorded for posterity, but clearly Bunning threw well over 100 pitches in his 10-inning effort.

In the chapter on the 1964 pennant race in It Ain’t Over ’Til It’s Over, Mauch’s decision to start Bunning on this date is called “inexplicable.”3 Kashatus says that Mauch was anxious to extend the Phillies’ lead in the standings and that the ninth-place Colts would seem to be perfect patsies for a pitcher of Bunning’s caliber even if he was not fully rested.4 Halberstam says Mauch wanted Bunning to pitch in every series the Phillies played down the stretch.5 Both Kashatus and Halberstam say Mauch wanted Bunning to pitch in Los Angeles, but he would have anyway, if he had not started in Houston.6 He would have opened the series in L.A. for the Phillies the very next day—and would have been in to start the opening game in the next series against the Reds, who still had some hope for the pennant, while the Dodgers had none. By starting in Houston, however, Bunning was indeed available to pitch the final game of the LA series, but that meant he would miss the Cincinnati series entirely, unless Mauch intended to use him again on short rest.

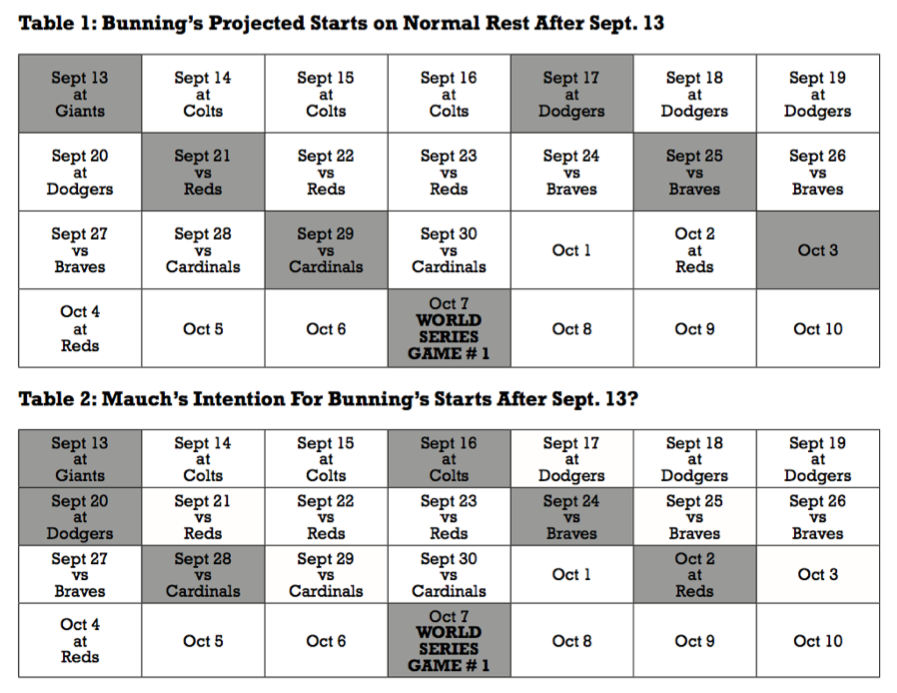

Those explanations might be true, but they don’t make sense, at least not to me. Why start Bunning on short rest? When we consider the calendar and that the Phillies were beginning to print World Series tickets, what emerges as the most plausible reason for this decision is that Mauch was trying to set up his best pitcher, Jim Bunning, to start the first game of the World Series—scheduled to begin on Wednesday, October 7—on suitable rest. (See table 1.) Ironically, had there been a game scheduled between the Phillies and Reds on Saturday, October 3, Bunning would have been perfectly lined up to start the World Series by making his last five regular-season starts on normal rest. But a quirk in the scheduling had the Phillies and Reds concluding the season with games on Friday, October 2, and Sunday, October 4, but with a day off on Saturday between the two games.

(Click image to enlarge.)

If this analysis is correct, Mauch faced a dilemma. If Bunning continued to pitch on his normal schedule, his last start before the World Series—assuming he was to start the first game, which of course was a given—would have been on September 29, giving him a full week off before the World Series began. (See table 1.) Starting pitchers especially establish a rhythm for pitching during the season, and Mauch probably assumed that seven days between starts was too long for a workhorse like Bunning, who might lose his edge with so much downtime.

Mauch could have decided to give his ace four days’ rest between his remaining starts, which would have had Bunning making his final start of the regular season on Friday, October 2, giving him another four days’ rest before the start of the World Series. But this would not have been a viable solution for Mauch even if he were willing to buck the then conventional practice of the top starting pitcher taking the mound every four days and to start Bunning every fifth day. With Culp out, Bennett hurting, and no depth in his rotation, Mauch really had no option to go to a five-man rotation until the World Series. Instead, he appears to have decided that keeping to the rhythm of three days’ rest between starts was preferable and took the gamble of starting Bunning—presumably just this once— on short rest against the woeful Houston Colts, in order to set him up to have proper rest before his final regular-season start on October 2. That would have given Bunning an extra fourth day before pitching in Game 1 of the World Series. (See table 2.)

In his Houston start on short rest, Bunning gave up six runs in 4 1?3 innings, leaving the game after giving up three hits and two walks to the six batters he faced in the fifth. At the time, it was a loss that had no bearing on the standings, and in fact the Phillies won the next day in the first of four games in Los Angeles, beating Don Drysdale, against whom Bunning would have pitched on normal rest, to increase their lead to 6½ games with 15 remaining. All seemed right with the world in Philadelphia, but Gene Mauch had made what in hindsight proved to be a disastrous decision: starting Jim Bunning on two days’ rest.

QUICK HOOK OF YOUNG STARTER HAS CONSEQUENCES

Although the Phillies did win 4–3 that next day, September 17, in Los Angeles, Mauch made another decision that would have unanticipated consequences down the road. He started right-hander Rick Wise, a rookie teen, instead of Art Mahaffey, whose previous two starts apparently had caused Mauch to lose confidence in him, according to several accounts, including Kashatus’s.7 Mahaffey had given up three runs in only two-thirds of an inning on September 8 in a 3–2 loss to the Dodgers in Philadelphia, and then two runs in two innings on September 12 in a 9–1 loss in San Francisco.

Wise was making only the eighth start of his career, however. Back in August, he did have back-to-back victories in which he pitched effectively into the eighth inning, but in his two starts immediately before this one on September 17 he did not pitch well. He gave up five runs in four innings to the Braves on August 25 and was removed by Mauch in the first inning of his next start on September 7 against the Dodgers after facing only three batters—giving up two walks and a single—all of whom scored. He got no one out.

Here was Wise starting against the Dodgers again, ten days later, and he already had a 3–0 lead from the top of the first, but this game began much the same way as his last start had. Wise had given up two singles, a walk, and a groundout resulting in two runs when Mauch decided that—even with a 6-game lead and a depleted starting rotation—he had seen enough for the day of young rookie Wise, who had turned 19 only days before. With left-handed batters Johnny Roseboro and Ron Fairly next up for Dodgers, Mauch called on veteran southpaw Bobby Shantz rather than let Wise try to work his way out of trouble and see if he might settle down.

At the time, it seemed like a brilliant move. Shantz pitched into the eighth inning and gave up only one run of his own to earn the 4–3 win that put the Phillies up by 6½ games. However, with Bunning and Short his only two healthy starting pitchers, Mauch had no pitchers to spare. Instead of showing commitment to his decision to start a young rookie in a late-season game during a pennant drive, Mauch replaced him in the first inning. In effect, he used two pitchers in one “starting role” that day. An unintended consequence was that Bobby Shantz, who faced 25 batters in relief of Wise, was unavailable to pitch in dire circumstances two days later.

The Phillies’ unraveling began the next two days with consecutive 4–3 losses in Los Angeles. Chris Short, starting on normal rest, took a 3–0 lead into the last of the seventh on September 18, having given up only two hits. Three batters later, the score was tied on a three-run home run by Frank Howard. The Dodgers won on a two-out single off Phillies’ relief ace Jack Baldschun with two outs in the ninth. The next day, September 19, the two teams battled into the sixteenth inning, tied 3-3, when Baldschun—having already worked two innings in this game and six innings in the previous four days—gave up a single to Willie Davis, intentionally walked Tommy Davis after Willie stole second, and then surrendered a wild pitch that advanced Willie to third with left-handed batter Ron Fairly at the plate.

Gene Mauch chose this moment to replace his relief ace with rookie southpaw Morrie Steevens, who was appearing in his first major-league game of the season and had only 12 appearances in the major leagues before this. Mauch had only one other left-handed option available, the crafty veteran Bobby Shantz, but Shantz had pitched 7 1?3 innings just two days before in relief of Wise and was not sufficiently rested—apparently not even to face one batter, although getting the out would have meant going into the seventeenth inning. Instead of staying with Baldschun to get one more out to escape the inning, Mauch went with Steevens. There were two out, and the possible winning run on third. As a left-hander, whether pitching from the stretch or from a full windup, Steevens on his delivery would have had his back to the runner at third. Steevens apparently was so focused on Fairly, as well he should have been, that he was inattentive to Willie Davis, which he should not have been; Willie Davis took advantage and stole home, scoring the winning run.

BUNTING DICK ALLEN

Mauch had an opportunity to win this game in the fourteenth inning, when Johnny Callison led off with a single. Dick Allen, the cleanup hitter, strolled to the plate. After Allen was the pitcher’s spot (the result of an earlier double switch) but, this being a long game in which he had already used seven position players off the bench, Mauch had limited options for a pinch-hitter. Specifically, he had the light-hitting Bobby Wine, who was batting .209, with only 4 home runs and 33 RBI, and hadn’t played in five days—except as a defensive substitute who did not get a chance to bat.

Allen, coming to bat with nobody out and Callison on first in the fourteenth inning of a tie game, was the Phillies’ most dangerous hitter. He already had 26 home runs for the year and was third in the league in slugging percentage. In his three previous plate appearances, he had two singles and been intentionally walked by the Dodgers. Even though he knew that Wine was to bat next, Mauch opted to play for one run rather than letting his cleanup batter hit with the possibility of driving in the run. He had Allen—his best and most feared hitter—lay down a sacrifice bunt. Allen did so successfully, but that left Mauch with only two outs to work with and two weak hitters—Wine, followed by .238-hitting catcher Clay Dalrymple—to try to drive in Callison from second. Callison was picked off, Wine flied out, and the Phillies failed to score, ultimately setting up Willie Davis’s game-winning steal of home. The loss still seemed relatively inconsequential, however, as Bunning came back on September 20, on his normal rest, to win his eighteenth game of the season, 3–2, both runs unearned in the ninth.

WITH 12 GAMES LEFT, THE PHILLIES FACE THE PERFECT STORM

We are now at where most accounts of the Phillies’ 1964 collapse begin. When the Phillies returned to Philadelphia on September 21 for their final homestand of seven games, they once again had a 6½-game lead over both the Reds and the Cardinals and were 7 games ahead of the Giants. Even if the Reds or Cardinals won all of their remaining games, the Phillies needed to win only 7 of their remaining 12 games to win the pennant outright. If the Cardinals or Reds won 10 of their last 13 games—which, in fact, St. Louis did— the Phillies could have finished the season 4–8 and still gone to the World Series. It would take nearly a perfect storm for Philadelphia to not win the pennant.

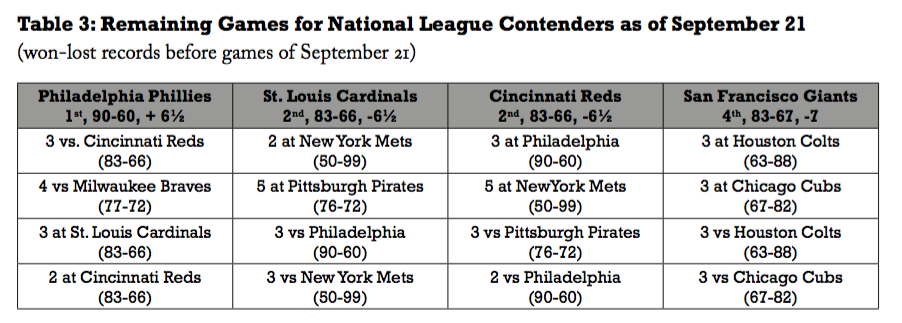

And, as fate would have it, the remaining schedule conspired to make that perfect storm plausible. (See table 3.)

(Click image to enlarge.)

The Reds had five of their 13 games remaining against the Phillies, and the Cardinals had three games left with the Phillies, giving both teams the opportunity to make up significant ground against the first-place team they had to overtake. But the Reds also had five games against the awful Mets and three against the struggling Pirates, who were in sixth place at the close of play on September 20. And the Cardinals had five against those awful Mets and five against those struggling Pirates. The Giants, who really shouldn’t have been in the discussion at this point, as any combination of six Phillies’ wins or six losses of their own would eliminate them from contention, had the advantage of playing their final 12 games against the eighth-place Cubs and ninth-place Colts.

The Phillies, however, did not have any of the National League’s worst teams on their remaining schedule. In eight of their final 12 games, they had to contend against their two closest competitors, the Reds and Cardinals—meaning they would lose ground in any game they lost. And the Phillies’ other four games were with the fifth-place Milwaukee Braves, whose potent lineup was well able to do serious damage to Mauch’s worn-out pitching staff, especially with his regular third starter, Culp, disabled with an elbow problem; his fourth regular starter, Bennett, enduring a sore shoulder; and both Mahaffey and Wise deemed less than reliable by their manager. The Phillies were scheduled to close the season with three games in St. Louis and two in Cincinnati. At this point, at the start of play on September 21, both the Cardinals and the Reds still had a dim chance, but Mauch had reason to hope they would no longer be a pennant threat by then.

To put their remaining schedules in a different perspective: The Reds and the Cardinals were playing teams (including the Phillies) with a combined winning percentage of .483 on the morning of September 21, while the Phillies were going against teams (the Reds, Braves, and Cardinals) with a combined winning percentage of .544—a significant difference. Philadelphia had a tougher schedule, but still, a 6½-game lead with only 12 remaining should have been safe, almost impossible to lose.

The Phillies seemed to have an advantage in that seven of their final 12 games were at home. With a 46–28 record at Connie Mack Stadium, the Phillies at this point had the best home record in the National League. Their first three games were against the Reds, who really needed to sweep the series to have a realistic chance of catching the Phillies. While there was nothing at the moment the Phillies could do about the Cardinals and the Giants, just one win in the three games would leave the Reds 5½ games back, a gap that would be virtually impossible to close with only 10 games left. How important would just one win have been? Even if the Cardinals swept their upcoming two game series with the Mets in New York, one Phillies win against the Reds would have left St. Louis five games behind with 11 remaining, and with not very much hope.

BUNTING DICK ALLEN AGAIN AS THE LOSING STREAK BEGINS

The Phillies lost the first game of their series with the Reds in dramatic fashion, 1–0, when Chico Ruiz stole home with two outs in the sixth inning. On his delivery, Mahaffey, back in the starting rotation, would have been facing the third-base line. Of course, with Frank Robinson, one of baseball’s most accomplished and feared batters, at the plate, the Phillies (including their manager) could be excused for assuming that an attempt to steal home in this situation was highly improbable. But steal home Ruiz did. Reds pitcher John Tsitouris was in command the whole game, pitching a six-hit shutout, and Philadelphia’s lead was down to 5½ games.

All accounts of this game mention that both Mauch and Reds manager Dick Sisler were shocked that Ruiz had the gall to try to steal home with Frank Robinson at bat. What they don’t mention is that the Phillies’ best chance for a run came when Tony Gonzalez led off the home first with a single, bringing up Dick Allen—whom Mauch had batting second in the lineup, rather than in a power slot, and whom he once again asked to sacrifice the runner to second rather than hit away with the possibility of setting up a big first inning. The Phillies had all 27 outs remaining, so why give up Philadelphia’s best, most effective hitter at this point in the game? If Allen got out and the runner was still on first, Mauch would have still had two outs in the inning and eight more innings to go. The sacrifice turned out to be good, but the runner ended up stranded on third.

This was the second time in three days that Mauch called for Allen to lay down a sacrifice bunt. The first time, as we have already seen, in the September 19 game in Los Angeles, Mauch had Allen bunt with a runner on first and nobody out in the 14th inning in an effort to break a 3–3 tie, despite knowing that none of the batters following Allen in the order were notable run-producing hitters. This time, in the first inning with nobody out, Mauch was hoping to set up an early run. With Dick Allen on his way to 201 hits, 29 of them home runs, an OPS of .939 (fifth in the league), and more total bases, 352, than anyone else in the league (Willie Mays had 351), Mauch’s decision to have Allen sacrifice-bunt is open to legitimate question, especially as most other managers did not use their most powerful hitters to lay one down for lesser lights to try to drive the runner home.

Allen batted .542 with runners on base during the 17 days that forever shocked Philadelphia. Had he been allowed to swing away in either of those plate appearances against the Dodgers and Reds, the outcome of either game, or of both games, might have been different. One more win at that point in the season, with so few games remaining, might have been all it would have taken to permanently deflate the hopes of the Reds and Cardinals before they began their surge upward.

Gene Mauch’s reputation as manager was that he tended to call for plays—the sacrifice, the hit-and run—to work for one run at a time, even from the very beginning of the game, in order to score first if at all possible. The problem is that sacrificing an out to help set up a run is precisely that—giving up an out, and there are only three outs an inning and 27 a game. While this strategy made sense for managers of teams (Walter Alston, for example, with his mid-1960s Dodgers) that had difficulty scoring runs, Mauch had a lineup with much more ability to score runs. Even so, he often chose to sacrifice for one run—even with his best hitters at the plate—instead of trusting in his firepower.

The two best hitters in the Phillies’ lineup, Allen and Callison, who hit a combined total of 60 home runs in 1964, both, in the course of the season, laid down six sacrifice bunts to move a base runner up with nobody out. In calling for them to do so, Mauch, in the interest of playing for one run, gave up as outs the two batters most likely to drive in runs. Of the league’s other premier hitters who also hit for power, Willie Mays had one sacrifice bunt for the Giants in 1964, Orlando Cepeda and Willie McCovey none; Frank Robinson did not have a sacrifice all year for the Reds; neither did Ken Boyer for the Cardinals; nor did Hank Aaron or Eddie Mathews for the Braves. Milwaukee, in fact, had five players who hit 20 or more home runs, only one of whom had any sacrifice hits—Denis Menke, not otherwise known as a power guy, with four.

WHERE SHOULD DICK ALLEN HAVE HIT?

WHERE SHOULD DICK ALLEN HAVE HIT?

It seems Gene Mauch never decided where the appropriate place in the batting order was for his rookie phenom, Dick Allen, in 1964; he changed his mind about that at least three times. In the first part of the season—64 games from opening day through June 12, during which the Phillies went 29–21 (.580)—the powerful Allen most often batted second, a lineup spot usually used to help set up runs for the third, fourth, and fifth hitters. Allen batted cleanup only three times in the first two months of the season—understandable, given that he was still an unproven rookie. By this point in the season, June 12, he was batting .294 and had 12 home runs and 32 RBIs, leading the Phillies in all three triple-crown categories. Allen also had an .895 OPS. Aside from his power numbers suggesting that the third or fourth slots in the batting order would have been a more logical fit for him, he also had a propensity to strike out a lot—not a good thing for a number-two batter. Allen led the league in strikeouts in 1964 with 138, averaging one strikeout every five at-bats when he batted second in the order.

Seeing what his emerging young slugger could do, Mauch put Allen into the cleanup spot on June 13, where he stayed for 53 of the Phillies’ next 55 games, during which they went 33–22 (.600). By August 6, Allen was batting .311 and had a .913 OPS, with 19 home runs and 56 RBIs. On August 7, however, right-handed power-hitting Frank Thomas joined the Phillies to fill their glaring weakness at first base. From then until September 17, Mauch alternated Thomas with the left-handed Wes Covington in the cleanup spot. Of the 42 games played in that time, Allen batted fourth only twice and once again was used most frequently (23 times) in the number-two spot of the lineup, although Mauch also often had him batting third (17 times), with the usual number-three hitter, Johnny Callison, second in the order in those games. From looking at who the opposing starting pitcher was, it is not apparent that Mauch’s shifting of Allen and Callison between second and third in the order had anything to do with whether the pitcher threw left-handed or right-handed. The Phillies were 27–15 (.643) in their best stretch of the season, at the end of which Allen was batting a team-high .307 and had a teambest .913 OPS, with 26 home runs and 79 RBI.

Mauch, however, still had not settled on a permanent spot in the batting order for his most dangerous hitter. In the final 15 games, Allen batted fourth eight times, second five times, and third twice. He finished the season batting .318 (fifth in the league), with 29 home runs and 91 RBIs.

Would it have made a difference had Mauch stayed with Allen in the second or third slot in the final weeks, particularly when the games became desperate as Philadelphia’s lead evaporated? There is much to be said for lineup stability. There is also much to be said for a hitter batting cleanup who was as much of a power threat as Dick Allen was. In the final 15 games of the season, Allen continued to hit well even as the rest of the Phillies did not. While the Phillies as a team were terrible in the clutch with runners on base, especially in scoring position, Allen was . . . well, clutch. He went 13-for-26 with runners on base in those 15 games—a .500 batting average—and walked or was intentionally walked several times. He also had those two sacrifice bunts.

LOSING BUILDS MOMENTUM

After the Phillies’ dispiriting 1–0 loss on September 21, Chris Short was roughed up the following day in a 9–2 loss to Cincinnati, victimized by yet another steal of home (by Pete Rose, as part of a double-steal in the third) and by a two-run homer by Frank Robinson. And on September 23, in the final game of the series, Vada Pinson’s second home run of the day broke a 3–3 tie in the seventh as Cincinnati went on to a 6–4 win to sweep the series. Bunning, whose regular turn in the rotation would have had him starting the first game of this series if not for his short-rest start in Houston, did not pitch against Cincinnati.

The failure to take even one game from the Reds cost the Phillies three games in the standings in three days, but with a 3½-game lead and now only nine games remaining, it still seemed time was on their side. Moreover, the Cardinals and Giants were both five games back, presumably no longer in the picture. But for Philadelphia, the losing had become contagious. Bunning, pitching for the second time on his normal rest after his September 16 start in Houston, threw six strong innings on September 24 in the first of four games against the Braves, but the Phillies were held scoreless until the eighth in a 5–3 loss. But the Phillies had a three-game lead at the end of the day.

No need yet to be desperate, but Gene Mauch, feeling that the sure-thing pennant was slipping away, acted in desperation On September 25 he started Short, on only two days’ rest, instead of Mahaffey, whose turn it was in the rotation and who had pitched so well in his previous start (the one where he neglected to check Chico Ruiz at third). Kashatus suggests that Mauch did not start Mahaffey in this game because he felt that the pitcher had cracked under pressure when he allowed Ruiz to steal home.8 Short pitched effectively into the eighth inning, giving up only three runs on seven hits, but left trailing in the game. Callison tied the score in the eighth with a two-run home run, and the game went into extra innings. In the tenth, Joe Torre’s two-run home run for the Braves was matched in the bottom of the inning by Dick Allen’s two-run inside-the-park home run, which tied the game at 5–5. Milwaukee won in the twelfth, however, 7–5. As had been the case too often in recent games, Mauch’s Phillies were abysmal with runners in scoring position. In eight such at-bats in this game, they were hitless.

STAYING WITH SHANTZ TOO LONG

But things looked brighter the next day, September 26, when the Phillies took an early 4–0 lead behind Mahaffey against the Braves, only to once again go cold at the plate when there were opportunities to score runs. The game went into the ninth inning, the Phillies’ lead in the game whittled down to 4–3. Due up for the Braves in the ninth were two of baseball’s best hitters, the right-handed Hank Aaron followed by the left-handed cleanup hitter Eddie Mathews. The Braves’ pitcher, batting fifth in the order as a result of earlier maneuvers by Milwaukee manager Bobby Bragan, was scheduled to bat third in the inning. Fourth up in the inning, however, would be another dangerous right-handed batter, Rico Carty.

Despite this formidable array of mostly righthanded batters, beginning with perennial home-run threat Aaron, Mauch allowed southpaw Bobby Shantz to take the mound in the ninth. Shantz had gotten the final two outs of the eighth, coming into the game in a bases-loaded situation with one out. The Braves’ third run of the game was scored on a passed ball. The Phillies’ right-handed relief ace, Baldschun, was no longer available, having relieved starter Mahaffey in the eighth, and was followed by Shantz. With Aaron leading off the ninth, capable of tying the game on one swing, Mauch could have turned to right-hander Ed Roebuck, warming up in the bullpen. Instead, he stayed with Shantz.

He stayed with Shantz after Aaron started the ninth with a single. This made sense, since Mathews was a left-handed power hitter. He stayed with Shantz after Mathews singled even after the right-handed Frank Bolling was announced as a pinch-hitter. This maybe also made sense, since Bolling, the Braves’ mostly regular second baseman, was hardly a dangerous hitter, his average hovering slightly above .200. Bolling reached on an error, loading the bases. The Phillies had a one-run lead but had yet to secure an out in the ninth. Coming up to bat was the right-handed Carty. He had come into the game batting .325, with 20 home runs and 80 RBIs. Still, Mauch stayed with southpaw Bobby Shantz, when he had right-hander Ed Roebuck waiting in the bullpen.

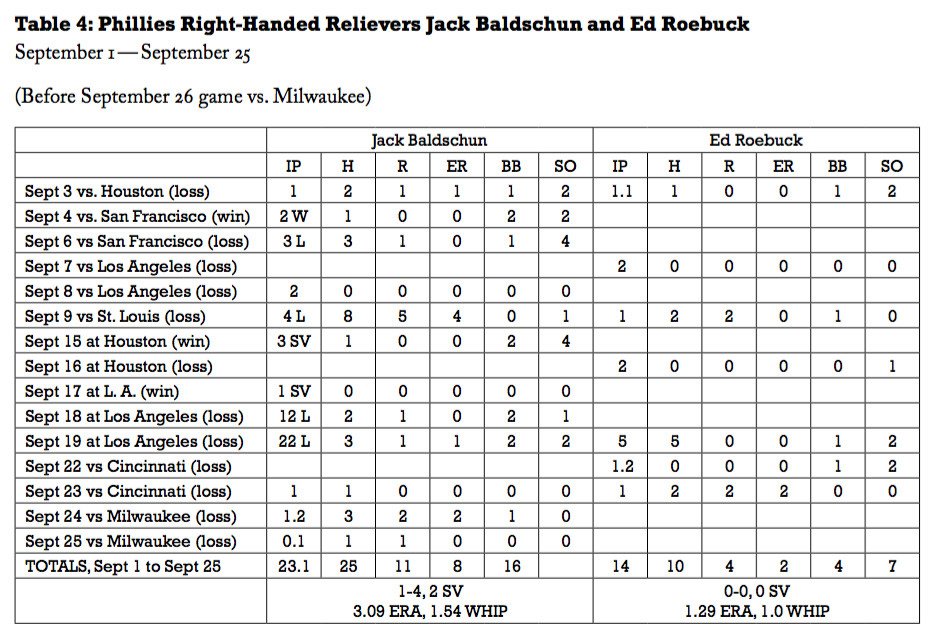

Why not turn to Roebuck? In a month when Mauch’s bullpen was stressed—relief ace Baldschun had lost four games already in September and allowed 37 of the 106 batters he had faced so far in the month to reach base, including one of two in this game before Shantz replaced him in the eighth—Roebuck had been pitching well. (See table 4.) In fact, Roebuck had allowed only four earned runs in his previous 14 appearances dating back to August 18. Two of those came on the three-run home run he surrendered to Vada Pinson that made him the losing pitcher in the final game of the series with Cincinnati. (See table 4.) That was three days ago. Presumably, Mauch no longer had much trust in Roebuck because he stayed with Shantz in a situation where he desperately needed an out. Carty tripled, the Phillies’ lead was gone, Shantz was removed from the game, and Mauch finally brought in Roebuck. The Phillies went down quietly in their half of the ninth.

Gene Mauch had now watched his team lose six straight games, eight of their last nine dating to September 18, and nine of eleven dating to when he decided to start Bunning on short rest against Houston. With the Reds having extended their winning streak to seven straight games, the Phillies’ lead was down to half a game. Meanwhile, the Cardinals, having won five of their last six, had closed to within a game and a half.

BUNNING AND SHORT IN DESPERATION STARTS

Now was truly desperation time for Mauch and the Phillies. Bunning told Halberstam he volunteered to pitch the final game of the Milwaukee series with only two days’ rest. With Bennett suffering through a sore shoulder, Mauch probably felt he had no other choice—certainly not 19-year old Rick Wise, who pitched to only four batters, giving up two runs, in his last start on September 17 and to only three batters in his start before that. Following a script similar to that of his short stint against Houston, Bunning gave up five consecutive hits before departing in the fourth without getting an out. All five hits led to runs in a 14–8 Milwaukee blowout in Philadelphia’s final home game of the season. Ironically, given that they lost, this was the Phillies’ first real offensive outburst since they beat the Giants, 9–3, way back on September 5 in Philadelphia. The Reds beat the Mets in a doubleheader, and for the first time since July 16 the Phillies were no longer in first place. Philadelphia was now down a game to Cincinnati and just barely ahead—by half-a-game—of the surging third-place Cardinals of St. Louis, the Phillies’ next destination.

(Click image to enlarge.)

The unintended consequence of his having started Short and Bunning out of turn against Milwaukee was that Mauch was now forced to use his two best pitchers on only two days’ rest between starts against the Cardinals—which were now a team they (the Phillies) had to beat to keep from falling behind yet another suddenly emergent pennant contender, let alone to keep pace with the Reds, against whom they would play their final two games of the season. Had they pitched in turn in the rotation, Short and Bunning would have been available to pitch on normal rest in the season series that now mattered the most—against the Cardinals, with the pennant at stake. Both did start in St. Louis, but on short rest, and both lost.

In the first of the three-game series, Mauch had Short making his third start in seven days. It was his second consecutive start on two days’ rest. Short pitched into the sixth inning, leaving the game trailing 3–0. His mound opponent was Bob Gibson, who was making 1964 the year that established him as almost impossible to beat when the Cardinals needed a win—as they did on this day—and Gibson delivered a 5–1 victory. As had become all too commonplace in their now-eight game losing streak, the Phillies had great difficulty with runners in scoring position, going 0-for-7 in this game. (See table 5.) Philadelphia was now in third place, 1½ games behind idle Cincinnati.

The next day, September 29, the Phillies got only one hit in nine at-bats with runners in scoring position—a two-run single with the bases loaded by pinch-hitter Gus Triandos—as they lost for the ninth straight time, 4–2. Bennett, starting with five days’ rest for his sore pitching shoulder, was much less effective than in his previous start. He got out of the first inning giving up only one run before being saved by a linedrive double play, but he gave up three consecutive hits and a sacrifice in the second before he could go no further. The Phillies lost no ground in the standings as the Reds lost to the Pirates; the Cardinals were now tied for first.

(Click image to enlarge.)

With only three games left and a game and a half back, the final game in St. Louis was critical for the Phillies. Once again, Gene Mauch asked Bunning, his ace, to pitch on two days’ rest. His only other option was Art Mahaffey, who had pitched into the eighth inning four days before, giving up only three runs against the power-hitting Braves. And the game before that, Mahaffey had given up only one run in 6.2 innings against Cincinnati, the game he lost, 1–0, because he failed to pay attention to the remote possibility (which became reality) that Chico Ruiz might try to steal home with two outs and Frank Robinson (Frank Robinson!) batting. Mahaffey was rested and he was pitching well, but for whatever reason Mauch did not trust him and chose to go with the worn-out Bunning, now making his fifth start in 15 days.

As was becoming predictable when he pitched on short rest, Bunning was battered around, giving up a two-run home run in the second, allowing five consecutive batters to reach base (one on an error) to start the third though only surrendering two runs, and leaving with one out in the fourth after consecutive singles. Both baserunners scored. After four innings, the Cardinals had an 8–0 lead on their way to an 8–5 win. They took a one-game lead over the Reds, who lost for the second straight time to the Pirates.

Then, blessedly for the Philadelphia Phillies, came their first day of rest since August 31. They had played 31 games in the first 30 days of September.

TOO LATE FOR A HAPPY ENDING

The day off on October 1 and another offday scheduled for October 3 meant that, in the final two games of the season, in Cincinnati, Mauch could start his two best pitchers, Short and Bunning, on their normal three days’ rest. Now in third place, trailing St. Louis by 2½ games and Cincinnati by two, Philadelphia could still finish the 162-game schedule tied for first if they won both their games against the Reds, and the Cardinals lost all three of theirs against the lowly Mets, which would create a three-way tie. Their only possibility of making the World Series, which ten consecutive losses ago seemed such a sure thing, would be to win a never-before three-way playoff series with the Reds and Cardinals to determine the pennant winner. It could have even been a four-way tie for first at the end of the scheduled 162-game regular season, but only if the Giants, who were now three games back, won all three of their remaining games against the Cubs in San Francisco and if the Cardinals were swept by the Mets and if the Phillies won both of their games against the Reds.

None of those things happened, except for the Phillies ending their 10-game losing streak by winning their final two games of the regular season against the Reds. In the first game, Short left in the seventh, trailing 3–0, but Dick Allen tied the socre with an eighth-inning triple and then scored what proved to be the winning run. The Cardinals, meanwhile, lost two games to the Mets, setting up a final-day scenario for a three-way tie (the Giants having already been eliminated by losing on Saturday to the Cubs). Pitching on normal rest, Jim Bunning hurled a six-hit masterpiece to shut out the Reds, 10-0, never allowing a runner past second base. Allen hit two home runs.

The Phillies were now tied with the Reds, both teams awaiting the outcome of the Cardinals game with the Mets in St. Louis. The Mets had a 3–2 lead in the fifth, but the score proved deceiving, as the Cardinals brought in Gibson in relief to shut down the Mets and scored three times in the fifth, the sixth, and the eighth on their way to an 11–5 victory and the 1964 National League pennant. For good measure, St. Louis went on to win the World Series that Philadelphia had seemed sure was theirs to play.

WAS GENE MAUCH GUILTY OF OVER-MANAGING?

Certainly Mauch’s strategic miscalculation in starting Bunning and Short on short rest against Milwaukee— before, arguably, he needed to resort to that, even if his starting rotation was in disarray because of the injuries to Culp and Bennett—and his hitters’ inability to take advantage of scoring opportunities contributed to the Phillies’ colossal collapse, which haunts Philadelphia to this day. But the question remains whether the manager may have cost his team the pennant by his penchant for overmanaging in game situations. Baseball can be unforgiving, quick to smack down those who think they can master the flow of the game. Mauch was an intense baseball man who prided himself on his intimate knowledge of the game. As a manager, he tended to be very hands-on.

Managerial brilliance can be a tricky thing. Managers are both strategists and tacticians in the dugout. They must navigate a delicate line between managing too much and managing too little. At the game level, managing too little could mean not anticipating how the game might play out given the current situation. Or it could mean not trying to force the action when the game situation might suggest that it should be forced. Managing too much, on the other hand, could mean trying so hard to force the action that the natural flow and rhythm of the game for the players is interrupted. The one managerial style could convey a lack of urgency, with the result that players lose focus and fail to execute or to exercise subtle skills. The other style, over-managing, could convey too much urgency, even panic, with the result that players play tight and do not follow, or in some cases even develop, their instincts for the game. This was a criticism that Dick Allen in particular made, according to Halberstam, Kashatus, and, in his autobiography, Allen himself. Over-managing is not necessarily indicative of managerial brilliance in game situations. It can, rather, indicate a manager’s overwhelming desire to maintain tight control over each game, perhaps for fear of the second-guessing that comes with losing. Or it can indicate that he does not fully trust his players’ instincts and ability or even (dare we say?) that he has some wish to prove his relevance to the outcome of games when it’s the players’ performance that is the obvious determinant.

Managers must understand what is most appropriate for their team and make adjustments to their styles and strategies when necessary. The 1964 Phillies probably would not have been in a position to win the pennant without Mauch as their manager, but his intensity (often manifested as sarcasm and the belittling of his players when things didn’t work out) and constant maneuvers to try to wrest the advantage in games may have caught up with him in the final weeks of the season. When it was all over, Mauch blamed himself for the debacle. This was telling not so much because he attempted to remove the stigma of the collapse from his players but because, in the final weeks, he may have put on himself too much of the burden to win games instead of allowing the games to play out with less urgency.

(Click image to enlarge.)

First he was in a rush to clinch the pennant, and he quite likely began preparing for the World Series prematurely when, with a 6-game lead, he started Bunning in Houston on short rest, probably so he would be aligned for Game 1 of the World Series. Then he overreacted to a string of defeats, especially to the Reds, that still left the Phillies in control of the pennant race with fewer than ten games remaining—if no longer in commanding control. Then, as the defeats piled on, he panicked as he tried desperately to pick up wins by starting his two best pitchers twice consecutively on short rest, wearing them down, when they, and especially Bunning, would have been more effective with normal rest.

The Phillies lost the pennant by one game. Even if Mauch had lost all of those games where he had no obvious starting pitcher (with Culp unable to pitch because of his elbow and Bennett badly hampered with a bum shoulder), Bunning and Short would have been more likely to pitch effectively and gain a victory on normal rest, as Bunning proved in both of his stretch-drive victories. Just one additional win by both, or two by either, could have changed the outcome of the pennant race. In effect, it may be that Mauch turned possible wins into losses by panicking rather than simply accepting losses for the sake of maximizing the odds of winning when his two best pitchers started.

If Mauch made his decision to start his ace on September 16 in Houston on only two days’ rest in order to line Bunning’s remaining starts up with Game 1 of the World Series—this appears to be the only plausible explanation, if you study the calendar—it suggests that at that point he took the pennant for granted. Joe McCarthy, by contrast, when he was managing the Yankees in the 1930s and 1940s, led pennant-winning teams that typically finished strong and with a huge lead at the end of September.

Mauch apparently was willing to risk a loss by Bunning on short rest, for the purpose of setting him up for the World Series. But the National League pennant had not yet been clinched. Perhaps Mauch should have waited for his Phillies to officially clinch the pennant before trying to arrange the rotation so that Jim Bunning would be able to start Game 1 of the World Series with the appropriate rest between his final regular-season starts. There likely would have been time enough for that.

While one could argue that the impact of his starting Bunning in Houston on September 16 could have been mitigated had Mauch thereafter kept Bunning on a normal schedule, this decision of his had a devastating cascading effect as the Phillies went into their 10-game losing streak, because Bunning turned out not to be available to pitch against one of the remaining contending clubs, the Reds. In trying to prepare for the World Series, Mauch forgot the importance of starting his best pitchers in their appropriate turn. Baseball has a way of punishing hubris.

BRYAN SODERHOLM-DIFATTE, who lives and works in the Washington, D.C., area, is devoted to the study of Major League Baseball history.

Notes

1 David Halberstam, October 1964 (New York: Villard Books, 1994); William C. Kashatus, September Swoon: Richie Allen, the ’64 Phillies, and Racial Integration (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2004); Steven Goldman, ed., It Ain’t Over ’Til It’s Over: The Baseball Prospectus Pennant Race Book (New York: Basic Books, 2007).

2 Clifford Corcoran, “There Is No Expedient to Which a Man Should Not Avoid to Avoid the Real Labor of Thinking,” in It Ain’t Over ’Til It’s Over, ed. Goldman, 134.

3 Corcoran, 141.

4 Kashatus, 118.

5 Halberstam, 303.

6 Kashatus, 119; Halberstam, 303.

7 Kashatus, 119.

8 Kashatus, 124.