Minnesota Twins team ownership history

This article was written by Gary Olson

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

The Minnesota Twins have called Target Field home since 2010. (COURTESY OF STEW THORNLEY)

The Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul have long been a baseball mecca. The Minneapolis Millers and St. Paul Saints were Triple-A mainstays, and each had a long and distinguished history, being the two teams with the most wins since the founding of the American Association in 1902. In the early 1950s, it seemed that this might be a permanent situation, as the 16 major-league teams were located in just 10 cities — New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Cleveland, Detroit, Boston, and Washington — with four of these having two teams and New York having three. The major leagues had a decidedly Northeastern slant.

Several things happened in the 1950s that gave the Twin Cities hope. One was demographic. In the 1950 Census for the first time the combined population of Minneapolis and St. Paul, including its growing suburbs, was over a million. The Twin Cities were now seen as one of the major population centers, but were noticeably without a major-league team, along with Los Angeles, San Francisco, Baltimore, and Buffalo, all in the top 15 in population.1 The Twin Cities had the Minneapolis Lakers, to be sure, but the NBA in the 1950s was still a backwater league, as were the NFL and the NHL. Only baseball was really “major league.”

In reaction to the demographics, the stability of the 16-team baseball pantheon began at long last to change. The Boston Braves gave up competing with the Red Sox and moved to Milwaukee in the spring of 1953. Later that year, the St. Louis Browns moved to Baltimore and became the Orioles for the 1954 season. In the fall of 1954, the Philadelphia Athletics announced they were moving to Kansas City for the 1955 season. The A’s and the Browns did sound out the Twin Cities option, but looked elsewhere when it was clear that there was no adequate ballpark for their teams to play in.2 Later in the decade, of course, the major change in baseball took place when in 1957 the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants moved to the West Coast for the 1958 season. But that gets us a bit ahead of our story.

After World War II there were those in the Twin Cities who felt that the Minneapolis-St. Paul area should have a major-league baseball team. By the early 1950s, what got the attention of those most serious about this was that both Milwaukee and Baltimore had succeeded in attracting major-league clubs because they had major-league-caliber ballparks to offer.3 So the effort to attract major-league baseball to the Twin Cities turned its focus toward creating a suitable ballpark. Both the Millers and the Saints played in old, entirely inadequate facilities that would not attract any major-league club.

Still, in the 1950s the long-standing animosity between Minneapolis and St. Paul was still very much alive. While St. Paul was the slightly older city, and was the state capital, Minneapolis had emerged as a much more vibrant commercial center, and by the 1950s was the larger of the two cities. This led to the ironic situation of the two cities independently pursuing the ballpark strategy.

The option pursued by St. Paul was, in some ways, an ideal one. It was focused on the Midway District, an area west of downtown St. Paul and, interestingly, close to downtown Minneapolis. In November of 1953, Walter Seeger, who owned a St. Paul refrigeration company, led a group of St. Paul boosters to get a $2 million referendum passed for a ballpark to be built in the district.4 Midway Ballpark, as it was called, opened in 1957, with a capacity of 10,250, and was used by the St. Paul Saints until 1960.5

The action that would eventually pay off in drawing major-league baseball to the Twin Cities occurred in Minneapolis. In the summer of 1952, Charles Johnson, Gerald Moore, and Norman McGrew began the long process of organizing an effort to attract a team to the area.6 Johnson was a sports editor and columnist for the Minneapolis Star and Tribune. Moore, a sales manager for a moving and storage company, was the president of the Minneapolis Chamber of Commerce and later the head of the Minneapolis Downtown Council. McGrew had been hired by the Chamber of Commerce with two initial responsibilities: keep Northwest Orient Airlines in town, and lure a big-league team to the area.7 While many others would eventually get involved, these were the founders of the drive to get a major-league team. The discussions among these founders soon focused on where and how to build a ballpark.

The efforts focused on a site near the Minneapolis-St. Paul Airport, in Bloomington. Their thinking was influenced by the emerging need for adequate parking, now that fans overwhelmingly came to games by car. The site was equally distant from both downtowns, though it was not close to either.

In 1954 a Metropolitan Sports Area Commission was formed to carry on the business of creating a ballpark that would attract a major-league franchise. An organization called the Minute Men was formed to raise funds for the ballpark. They put together a bond program worth $4.5 million to provide the initial funding, though in the end the facility as built would require double this amount. The plan was to create a ballpark seating 20,000 that would initially be used for minor-league baseball, but could easily be expanded to 40,000 if a major-league team committed to coming to the area.8

The proposal for the ballpark, used to attract investors, emphasized the greater Bloomington site as a community resource. There were many ideas for uses of the land beyond just a ballpark and its vast parking lots. The investment prospectus even spoke optimistically of a team committing to move to the area in time for the 1956 season, when it was expected that the ballpark would be ready for occupancy. Interestingly, the proposal for a ballpark emphasized that the community would share in the income from ballpark activities. Ticket sales, concessions, even parking, would be shared between the occupying baseball team and the community. There was even language about sharing future television income, to help to service the bond debt. Though the initial plans were to hold the City of Minneapolis harmless in this bond drive, in the end the city had to agree that it would step in to cover the debt service if income from the ballpark did not meet the need. And later, when the ballpark needed to be expanded from 20,000 seats to 40,000, the city had to step in to refinance the entire package.9

Ground was broken for the new ballpark in Bloomington on June 20, 1955, on 160 acres of land just south of what would later become Interstate 494. It took less than a year to build. The first game was played on April 24, 1956, with the Minneapolis Millers facing the Wichita Braves. It was only in July that the ballpark picked up its official name: Metropolitan Stadium. It affectionately came to be known as The Met. Its seating capacity at opening was 18,200; later during the Millers’ occupancy, it settled at 21,000. Now the Twin Cities had a ballpark. Well, actually, two, as St. Paul went ahead with the construction of Midway Stadium; but Midway was never a serious option in the attempt to lure a major-league team.

During the early phases of trying to attract a team, there were multiple indications that the team that moved to the Twin Cities would be the New York Giants. The Millers were the Giants Triple-A farm club. Giants owner Horace Stoneham attended an early Millers game at the Met, and said it was one of the best ballparks in all of baseball. In May of 1956 he had said publicly that he was considering a move to Minneapolis.10 All kinds of signals encouraged the Minneapolis organizers to have high hopes that this was really going to happen. In later discussions Stoneham and Minneapolis representatives talked through details of the move, even discussing the price of popcorn at the ballpark.11

The fall of 1956 saw fateful events in the saga to land a team. During the 1956 World Series, representatives of the Los Angeles effort to land a team had a conversation with Calvin Griffith about moving the Washington Senators to Los Angeles.12 Griffith was quite attracted to the idea. In the end the Senators decided that they did not want to leave Washington, though one rumor was that during the 1956 World Series, Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley had scribbled a note to Kenneth Hahn, who was representing Los Angeles, asking him not to proceed with Griffith because he wanted to bring the Dodgers to LA.13 But regardless of the accuracy of this story, it is interesting that later, as we shall see, O’Malley played an important role in getting the Senators to move to the Twin Cities.

The fall of 1956 saw fateful events in the saga to land a team. During the 1956 World Series, representatives of the Los Angeles effort to land a team had a conversation with Calvin Griffith about moving the Washington Senators to Los Angeles.12 Griffith was quite attracted to the idea. In the end the Senators decided that they did not want to leave Washington, though one rumor was that during the 1956 World Series, Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley had scribbled a note to Kenneth Hahn, who was representing Los Angeles, asking him not to proceed with Griffith because he wanted to bring the Dodgers to LA.13 But regardless of the accuracy of this story, it is interesting that later, as we shall see, O’Malley played an important role in getting the Senators to move to the Twin Cities.

Stoneham and the Giants were eyeing the Twin Cities quite apart from the Bloomington ballpark effort. In 1948 Stoneham had purchased 40 acres of land in St. Louis Park, west of Minneapolis, as a site for a potential new ballpark for the Millers, an act that no one knew about during subsequent ballpark discussions.14 Though no ballpark was built on that site, if one had been there, it might have put the Twin Cities in the running for the relocation of the Browns and A’s.15 Stoneham’s interest persisted. On a drunken evening in early 1954, he told the Millers’ general manager, George Brophy, that he would move the Giants to Minneapolis and that Cincinnati would move to New York to compensate for the Giants move.16 Obviously, hopes were raised.

As late as March 23, 1957, Horace Stoneham told Walter O’Malley in a private conversation that he had made a commitment to move the Giants to Minneapolis.17 O’Malley asked Stoneham if he might be interested in San Francisco, and Stoneham replied that he “was not at all impressed by that location.”18 In April of 1957 several members of the Sports Area Commission met with Stoneham in New York to discuss details of what a deal would look like, and came away with high hopes that a deal was soon to be consummated for a Giants move to Minneapolis.19 However, as events transpired, the possibility that the Giants would move to Minneapolis diminished. There is a lot of mythology about O’Malley’s role in changing Stoneham’s mind.20 However, the primary impetus came from the new mayor of Stan Francisco, George Christopher.21 O’Malley helped Christopher in arranging contact with Stoneham, but it was Christopher’s hard work with the leaders in San Francisco and his persuasiveness with Stoneham that cemented the deal.22

In May the Giants announced to the world that they would move to the West Coast, and Cincinnati would move to New York, to restore a National League team to the area.23 By August the Giants board of directors approved the move. The Giants, in contrast to the earlier moves of the Browns/Orioles, Braves, and Athletics, cut a very attractive deal. San Francisco promised to build a ballpark seating 40,000 to 45,000, with parking for10,000 to 12,000 cars. Concession revenues would go to the Giants. Rent for the ballpark would be capped at 5 percent of revenue. The team would control the venue for all other events. The Giants would get to approve the ballpark’s design.24 In return for these attractive terms, the Giants signed a 35-year lease.25 These terms were beyond what the Twin Cities operators had been considering.

This left the Twin Cities out in the cold. There were brief discussions with the Cleveland Indians, but legal issues concerning the Indians’ ballpark lease put an end to that.26 The Twin Cities group then turned their attention to Calvin Griffith and the Senators. The Senators’ situation was grim. Griffith was one of the last of the traditional baseball owners and the Senators were his only source of income. They had done poorly on the field for many years, and attendance lagged. By the summer of 1958 Griffith was seriously interested in moving, and the Twin Cities were his primary target. But the other American League owners opposed this. They were particularly anxious about hearings taking place in the US Senate just then over revoking baseball’s antitrust exemption. The feeling was that it would be a huge political disaster to take the team out of the Washington area. Indeed, Griffith even testified before the Senate committee that he would never leave DC as long as he could make ends meet.27

However, Griffith continued his overtures to the Twin Cities. The Senators and the Phillies played an exhibition game at the Met just after the All-Star game in 1958, and Griffith made his first visit to the Twin Cities for that game. He had previously worried about Minnesota, thinking it was a cold backwater. But Griffith was impressed by what he saw and heard. He liked the Met as a venue, and found the area in the middle of the summer to be quite lovely.28 Now the Twin Cities boosters once again felt they had a live one on the line. What would it take to confirm the deal?

The Twin Cities group took up one key issue: making the Met ready for a major-league occupant. The Millers were still playing there, though in December of 1957 the Boston Red Sox took over the ownership of the Millers. During the negotiations for the lease of the Met, the Red Sox insisted on an option for a major-league team. Joe Cronin, general manager of the Red Sox, was Calvin Griffith’s brother-in-law, and likely he was acting as a stalking horse for the Senators.29

In the second half of 1958 there were complex machinations involving the boosters, the Board of Estimate and Taxation, and the investors in the ballpark. The boosters realized they could not raise the total amount needed to expand the ballpark, so they wanted to buy out the earlier investors and refinance the entire deal for an expanded ballpark (estimated to cost $9.5 million) through general-obligation bonds backed by the taxpayers of Minneapolis.30 The Minneapolis City Council passed a resolution to sell such bonds, but put a sunset clause in it. If there was no commitment from a major-league team by January 1, 1959, there would be no bond sale and no ballpark expansion. Despite the Minnesotans’ guarantee of 750,000 fans a year for at least three years, Griffith once again balked.

So once more things were at a standstill. But several major developments finally broke the logjam. The first was Branch Rickey’s proposal to form a third major league, the Continental League.31 A number of large US cities wanted major-league baseball, and Rickey was able to gather together commitments from the Twin Cities, Houston, Denver, New York, and Toronto to form the initial franchises for the Continental League. The Minnesota lead on this venture was merchant banker Wheelock Whitney, who soon formed a close and enduring bond with Rickey. Wheelock’s partnership group included Bob Short, George Pillsbury, members of the Dayton family (Dayton-Hudson stores and Target) the Minneapolis Star & Tribune and Hamm’s Brewing. Throughout the summer of 1960 a series of negotiations both within the Continental League and with the existing leagues took place. To succeed, Rickey had to get Organized Baseball to recognize the new league, which he hoped would allow him to stock Continental League teams with real major-league players. But major-league baseball was reluctant to do this.

The other development was the proposal to create a new professional football league, the American Football League. The logic underlying this effort was similar to Rickey’s: create new franchises as a threat to the existing league, and either get them to expand, or else create viable franchises in up-and-coming urban areas not currently covered by the existing league. The Twin Cities were one of the original sites for a new AFL franchise.

These developments put enormous pressure on baseball’s major leagues. And particularly, it highlighted the dire straits of the Washington Senators. There were active discussions again in late 1959 about a move to the Twin Cities, but again the American League owners refused to grant their permission.

However, 1960 “would be the most historic year in Twin Cities sports history.”32 The Continental League organizers met in the Twin Cities in January and created local enthusiasm for the idea that maybe the path to major-league status went in this direction. Just the previous November the first full meeting of the AFL had been held in Minneapolis, and it seemed that this was the best path to a professional football franchise, as the established National Football League had shown reluctance to expand.

In the wake of those meetings, things moved quickly. On January 28, 1960, the NFL awarded the Twin Cities a new franchise, beginning with the 1961 season, with games to be played at the Met. The Met’s capacity would increase from 22,000 to over 30,000 in 1961, and later, when the Vikings would add double-decked stands in left field, to over 45,000.33 In March, the Minneapolis Lakers of the NBA announced that they were moving to Los Angeles.

Metropolitan Stadium in Bloomington, Minnesota, served the American League’s Minnesota Twins for 21 seasons. However, it was originally the home of a minor-league team, the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association. (COURTESY OF STEW THORNLEY)

Baseball soon followed. In July the two expansion committees of baseball, chaired by Walter O’Malley of the Dodgers and Del Webb of the Yankees, contacted Rickey and said they were considering expansion. After discussions, the two chairs announced that the major leagues would expand. The American League would create two new franchises, in Washington and Los Angeles, and allow Griffith to move to Minnesota for the 1961 season. The National League would expand to Houston and New York in 1962. Rickey of course noted the irony that only Houston and Minnesota were new areas. But this was enough to result in the death of the Continental League, which was one of the conditions laid down by the two major leagues.34

When it came to naming the new major-league franchises, both the football and baseball owners in the Twin Cities chose the novel idea of using the state name rather than the city. The Twins had actually proposed that the name be Twin Cities, but the American League rejected this. The owners at least allowed the Twins to use the interlocking “TC” on their caps.35 Using the Minnesota name was, of course, a way of appeasing the Minneapolis and St. Paul interests. This set a precedent for later sports franchises in other states, but the NFL Minnesota Vikings and the Minnesota Twins were the first.

By October of 1960 the deal was in place. The old Senators (the new Washington team would assume the Senators name) would be moving to Minnesota. The form of the deal was not quite what the Giants had received from San Francisco, but Griffith was pleased. He signed a 15-year lease. He got 90 percent of the concession revenues. The Sports Area Commission got 7 percent of ticket revenues as rent for the ballpark. No rent was required for the remainder of the lease if the Twins didn’t draw at least 750,000 fans in each of the first three years. The Twins also controlled concessions for other events at the Met, including Vikings games. This would come back to color relations between the Twins and Vikings later when a new ballpark was under consideration. Griffith also got a $600,000 broadcast deal for radio and TV, more than twice what he had in Washington. The other issue to be negotiated was indemnity payments to the Millers and Saints owners. The local community pledged $225,000 toward these fees. Interestingly, Walter O’Malley, who still controlled the Saints, allowed a generous grace period for the payment of his indemnity fee.36 So the Twin Cities had a major-league baseball team, beginning with the 1961 season.

Calvin Griffith was welcomed to the Twin Cities with open arms. After all the deals were in place, he showed up on November 4, 1960, to an enthusiastic reception. He was met at the airport by both the mayor of Minneapolis and the governor of Minnesota. The story made the front-page in the Minneapolis and St. Paul newspapers. He bought a home in the tony community of Wayzata on Lake Minnetonka, and even that was covered in the papers, with profiles of both Calvin and his wife, Natalie.37

Calvin Griffith’s history in baseball was somewhat unusual. He was born into a large family In Montreal in 1911. The family struggled with father James Robertson’s alcoholism, which led to his early death in 1923. In the summer of 1922, Calvin and his younger sister, Thelma, moved to Washington to live with Clark Griffith, whose wife, Addie, was James Robertson’s sister. The youngsters were raised as members of the Griffith family, and though they were never formally adopted by the Griffiths, both took their surname. Calvin began his baseball involvement as a batboy with the Senators in 1922, and he continued for several years, before entering Staunton Military Academy in 1928. He graduated in 1933, and then spent two years at George Washington University. He played baseball at both schools. He left George Washington in 1935 to become the secretary-treasurer of the Senators’ Chattanooga farm team. He had a series of increasingly important positions with the Senators’ farm clubs before returning to Washington in 1941 to become assistant secretary of the Senators. He began taking on more and more responsibilities with the Senators, and in 1955, when Clark Griffith died, he was elected president of the Senators.38

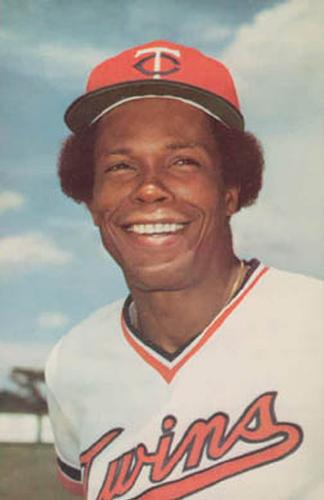

Several aspects of the franchise’s player roster were encouraging. Griffith had developed the Senators farm system, and it was beginning to pay off, with promising young players like Harmon Killebrew, Bob Allison, Jim Kaat, Jimmie Hall, and Rich Rollins.39 The Senators’ long interest in Cuba had also paid off, with their great scout Joe Cambria working his connections to sign promising young players like Camilo Pascual, Pedro Ramos, Zoilo Versalles, Sandy Valdespino, and Tony Oliva.40 The investments made during the late Senators era began to mature as the team relocated in Minnesota. Good attendance gave Griffith money to work other key trades, and hire such important on-field talent as Johnny Sain and Billy Martin.41

The 1960s turned out to be perhaps the best decade in Twins history, though the first decade of the twenty-first century had a lot to offer as well. The young Twins team in 1961 was entertaining, and the Minnesota fans responded by filling the seats to the tune of 1,256,723 attendance. This was much better than the 750,000 promised by the boosters, and coupled with the sale of Senators assets (like Griffith Stadium in Washington), gave Griffith a profit better than he had seen in years. He was able to adjust salaries in the front office, the latter largely populated by the Griffith family. He also began serious investments in the minor-league system, which over the years would be one of the crown jewels of the Twins franchise. The Twins also spent $400,000 on improvements to Met Stadium, which also was being upgraded to host the Vikings.

The 1962 Twins were even more exciting, finishing in second place with a 91-71 record, the best record in the franchise since 1945, and drawing an American League high attendance of 1,433,116. Emotions were running high that perhaps the Twins were on the verge of championships. This was not to be. The 1963 Twins got off to a slow start but were able to finish in third place with a 91-70 record. But the ’64 team fell to 79-83, and attendance dropped, though still above a million.

One staff move that would color much of the rest of the decade was hiring Billy Martin as manager. He had played for the Twins under Sam Mele during the 1961 season, and was very popular with the fans. Martin turned down a lucrative contract offer to play in Japan, and instead settled for a lot less money to work for the Twins as a scout. He was a good scout, and landed some players who would help the Twins in coming years. One major miss by the Twins was when Billy advocated the signing of a young pitcher named James Palmer, but Griffith balked. Palmer became a Hall of Fame pitcher with the Orioles.42 Martin behaved well as a scout. Even though he signed a contract as a sales rep with Grain Belt Brewery, he never got in trouble. After the 1964 season the Twins hired him as their third-base coach. He brought many innovations to player training and strategy.43 He would get a lot of credit from the press and the fans. In particular, he had a lot to do with the development of Zoilo Versalles, who was the American League MVP in 1965.

The 1965 season was the major breakthrough. The franchise won its first pennant since 1933. The Twins also hosted the 1965 All-Star Game. Minnesota was clearly on the national stage. Despite losing the World Series to the Dodgers in seven games, they were an exciting and attractive franchise. The Twins again had a record attendance, 1,463,258. Game Seven of the World Series drew 50,596, unprecedented in the history of the franchise. Sandy Koufax broke their hearts with a masterful 2-0 shutout on two days of rest. But baseball excitement in the region was at an all-time high.

In 1965, the Minnesota Twins won their first American League pennant and narrowly lost the World Series to the Los Angeles Dodgers. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

The 1966 season did start out well. Many of the core players were in decline because of age or injuries. By midseason the Twins had fallen to seventh place, 19 games out of first. However, the second half of the season was much better, and the Twins eventually finished second, though nine games out of first. One further episode colored the season. Martin and Howard Fox, the traveling secretary, got into a shouting match on the flight after a game, and then engaged in fisticuffs when they arrived at the hotel.44 It was Martin’s first serious breach of conduct with the Twins. While the Twins would continue to be upbeat about the possibility of Martin becoming manager, it at the very least colored his relationship with a key staff person.

The Twins again started slowly in 1967, and as a result, Griffith decided to let manager Sam Mele go. There were rumors that Billy Martin was next in line to manage the Twins, but the recent dust-up with Fox was still in Griffith’s mind, so he chose Cal Ermer. After Ermer took over, the Twins started playing much better, and going into the last weekend needed just one win in a two-game set in Boston to win the pennant. They failed. Boston won both games, and when the Tigers lost on the last Sunday, the Red Sox were the pennant winners. But the Twins were an exciting team, and they set a franchise attendance record that year, 1,483,547, topping even their pennant-winning year.

In 1968, the Twins Triple-A farm club, the Denver Bears, started out slowly. After their record fell to 8-22, the Twins fired John Goryl as manager and offered the job to Billy Martin.45 Martin thought this was a move to get him out of the Twins organization, but his wife convinced him that it would be a chance to show off his managerial talent, and increase his odds of getting a major-league job.46 Martin turned the team around, and they went 65-50 the rest of the way, playing “Billy Ball,” which featured such things as aggressive baserunning, lots of attention to details, and “punishments” for counterproductive play such as pitchers giving up too many walks or fielders throwing to the wrong base.47 This performance would result in Martin being hired to manage the Twins in 1969, though as Calvin Griffith said of Martin, “I feel like I’m sitting on a keg of dynamite.”48

Under Martin the 1969 Twins won the American League’s Western Division by a handy nine games. But in the new divisional format for the first time, they lost three straight playoff games to the surging Baltimore Orioles. At the end of the season, Calvin Griffith decided he could no longer put up with Martin’s antics, and fired him. Most notably, Martin had gotten into a fight with Twins pitcher Dave Boswell outside a bar in Detroit in August.49 Such shenanigans followed Martin’s career as manager with Detroit, Texas, Oakland, and, notoriously, with the New York Yankees. Interestingly, while Griffith was unhappy with Martin, the fans loved him, and the “Win! Twins!” bumper stickers of the 1960s were replaced with “Bring Billy Back.”50

Martin was replaced by Bill Rigney for the 1970 season. Rigney had played and managed the Minneapolis Millers, so was a familiar figure in the Twin Cities. His 1970 Twins also won the American League West, but were swept again by the Orioles in the postseason. The 1970 Twins drew more than a million fans to make the decade a clean sweep of million-plus attendance years.

That first decade in Minnesota was a great time for the franchise. They had drawn over a million fans each year. They had played in the World Series. The franchise was in the best financial shape it had been in for a long time. The success at the end of the decade, with two division titles, was encouraging, even if the playoffs had been disappointing.

But there were troubles on the horizon. Their co-occupants of the Met, the Vikings, were unhappy with the venue. They had invested their own money in creating a double-deck stand in left field. But the ballpark was clearly designed for baseball, not football, and the Twins got the concession revenue even when the Vikings played. As the 1970s began, the Vikings were starting to rattle cages about getting a new ballpark. Both the Vikings and Twins had signed 15-year leases, which would expire in the mid-’70s, giving both franchises leverage on the ballpark front. Even for the Twins the Met was odd. When they moved to the Twin Cities, permanent stands had been built down the right-field line, extending both the main level and the second deck. But down the left-field line there was still an unsatisfying single-decked temporary stand, and there was no prospect of permanent stands being built there, as the Twins couldn’t afford it and the Vikings had no interest in stands that would be in the end zone for football. So though the Met was only 15 years old as the new decade began, both tenants were unhappy.

The ’70s would be a dismal decade for the Twins on the field. They drew more than a million fans only twice, in 1977 and 1979. The decade was dominated by the ballpark drama locally, and the changes in the financial situation in baseball nationally. There was considerable turnover in managers. Bill Rigney was replaced in midseason of 1972 by Frank Quilici, who was in turn replaced by Gene Mauch in 1976. In 1980 Johnny Goryl replaced Gene Mauch late in the season. Such managerial instability continued into the mid-’80s.

Calvin Griffith was always tight with his money. A commercial that had new catcher Butch Wynegar saying he loved baseball so much he would play for nothing cut to the smiling Calvin Griffith who said, “I sure do love that kid.”51 But of course this was in the midst of a dramatic change in baseball contracts. Free agency had arrived, and it immediately impacted the Twins. Their rising star pitcher, Bert Blyleven, was traded to the Texas Rangers in 1976 so Griffith would not have to deal with his impending free agency. The Twins got Mike Cubbage and Roy Smalley III in that trade, who would be mainstays of the team for a while. The 1977 Twins provided excitement on the field, with Rod Carew flirting with .400 and Larry Hisle and Lyman Bostock hitting with gusto. The Twins drew over a million fans again for the first time since 1970. But they lost Hisle and Bostock to free agency the next year.

In September of 1978 Calvin Griffith poisoned the waters for his star player, Rod Carew. He gave a speech to the Lions Club in Waseca, where he was unaware that a reporter for the Minneapolis Tribune was in the audience. He made numerous outrageous statements, such as “Carew was a damn fool to sign that contract. He only gets $170,000 and we all know damn well that he’s worth a lot more than that, but that’s what his agent asked for, that’s what he gets.”52 Even worse: “I’ll tell you why we came to Minnesota. It was when I found out you had only 15,000 blacks here. Black people don’t go to ballgames, but they’ll fill up a rassling ring and put up such a chant it’ll scare you to death. We came here because you’ve got good, hard-working white people here.”53

In September of 1978 Calvin Griffith poisoned the waters for his star player, Rod Carew. He gave a speech to the Lions Club in Waseca, where he was unaware that a reporter for the Minneapolis Tribune was in the audience. He made numerous outrageous statements, such as “Carew was a damn fool to sign that contract. He only gets $170,000 and we all know damn well that he’s worth a lot more than that, but that’s what his agent asked for, that’s what he gets.”52 Even worse: “I’ll tell you why we came to Minnesota. It was when I found out you had only 15,000 blacks here. Black people don’t go to ballgames, but they’ll fill up a rassling ring and put up such a chant it’ll scare you to death. We came here because you’ve got good, hard-working white people here.”53

These comments totally upset Rod Carew, and it led to his being traded to the California Angels in anticipation of his coming free agency. The Waseca speech also led to criticism of the Twins’ small number of black players, including trades involving outspoken black players (Ken Landreaux and Gary Ward) for white players.54 In addition, the Twins scouting focused on the Midwest and the Deep South, where they would not encounter that many outstanding black players. While in subsequent years many black players were signed, including Kirby Puckett from inner-city Chicago in 1982, Griffith never escaped the reputation established by the Waseca speech.

The emergence of free agency coincided with a changing landscape in baseball owners. Many owners now had considerable wealth from other lines of work. George Steinbrenner, who bought the Yankees in 1973, was the iconic owner of this new generation. He had access to a lot of money, much of it that of his ownership partners, and eventually a lot of power to negotiate good deals for TV and radio rights.55 As a result, he was able to land top players in the emerging free-agent market. Calvin Griffith, whose only income came from the Twins, was, in the words of Jon Kerr, “baseball’s last dinosaur.”56 Interesting, though, when Jim “Catfish” Hunter became available in late 1974 as baseball’s first free agent, allegedly Griffith was one of the owners who expressed an interest in signing him.57 Hunter signed with the Yankees. As Jay Weiner, sports reporter for the Minneapolis Star Tribune, put it, “Griffith couldn’t keep up with his 1970s competitors at the 1950s Met using 1930s strategies.”58

But the dominant story of the 1970s was the ballpark. The Met was no longer competitive with ballparks being built all over the major-league landscape. Starting with Dodgers Stadium in 1962, 13 new ballparks had been built for major-league teams, in many cases for joint residence with professional football. Many of them were built as circles, with movable stands to adjust the seating for football and baseball. In many ways, these circles were not ideal for either sport, since many fans were now farther away from the action. Only Kansas City built two ballparks, one for baseball and one for football, both of which continue to be lauded as ideal venues for their sports. New amenities, including luxury boxes, opened up new revenue streams. The Met was already obsolete, and there were no funding streams available for upgrades.59 The next ballpark in the Twin Cities, the Metrodome, would also be a latecomer to the joint football/baseball phase of construction, and would be behind the curve as well.60

Investigations into the possibility of a new ballpark started in 1970 with the Metropolitan Sports Area Commission. There were only six years remaining on the Twins’ and Vikings’ 15-year leases, so time was of the essence. Early discussions focused on a downtown Minneapolis ballpark, primarily for the Vikings. Vikings owner Max Winter was a huge fan of the idea, including having the ballpark covered.61 When Griffith got wind of these discussions, he was interested in joint tenancy. The idea of a covered ballpark was attractive to him too, although initially he wanted a movable roof so baseball could be played in the open air when the weather was good.

Meanwhile, Bloomington, the site of The Met, had ideas. The Met Sports Center arena opened in 1966 for the Minnesota North Stars, near Metropolitan Ballpark. Bloomington’s idea was to upgrade The Met for the Twins, and build a new ballpark for the Vikings.62 Despite these grand plans, Bloomington had no idea for how to finance this, and instead was going to rely on Minneapolis for support.63 In the end The Met was torn down to make way for the Mall of America, and even the Met Center was torn down not long after the North Stars moved to Dallas in 1993. The landscape for future professional sports was now tilted to downtown Minneapolis (though in the case of professional hockey, the new Minnesota Wild got an area in downtown St. Paul).

The impetus for a downtown ballpark was led by John Cowles Jr., the head of the Minneapolis Star and Tribune. He had many motives. Unlike other cities, the downtowns of Minneapolis and St. Paul were not plagued by white flight or other related issues. Natural economic forces had pulled people and business to the ring of suburbs surrounding the cities. Downtown Minneapolis retail sales had fallen by 5 percent by the early 1980s, while the comparable figure in the suburbs had risen by 12 percent because of the emergence of large shopping malls. A number of corporations had moved their headquarters to the suburbs: Prudential Insurance, General Mills, 3M, and Cargill. Cowles wanted the new ballpark to be built downtown to counteract these trends.64

But it wasn’t easy. There was resistance to the idea of spending public money on facilities for highly paid professional athletes. During this period it was common to hear comments like “If the jocks want a new ballpark, then the jocks can pay for it.”65 The Twin Cities were already investing in other cultural amenities: the Guthrie Theater in 1963, the Nicollet Mall in 1967, a new facility for the Walker Art Center in 1971, a new Orchestra Hall in 1974. It took seven years to get a stadium bill passed in the Minnesota legislature. But the forces for a new ballpark were inexorable. The new governor, Rudy Perpich, made its a priority.66 In 1977 a bill was enacted to construct a new facility; it required that there be no more than $55 million in public financing. The bill was “site neutral,” and a new agency, the Metropolitan Sports Facilities Commission, was set up to find a location for the dual-purpose facility.67 Perpich filled the new commission with a slate of seven Minnesotans who broadly represented the state.68

In 1978 an outdoor-baseball enthusiast, Julian Empson, organized a campaign group called “Save the Met.” It was largely populated by a political community centered on the West Bank of the University of Minnesota campus. They created quite a ruckus. In many ways, in the words of Jay Weiner, “For all time, they injured the image and spirit of the Dome.”69 Empson even went so far as to develop plans for the state to buy the Vikings and Twins and keep them at The Met. In the end it went nowhere, and the forces behind the building of the Metrodome went forward.

There was a stipulation in the legislation that the site for the ballpark would have to be donated or funded through private fundraising efforts. Cowles led the effort to raise the $15 million that was needed to purchase a downtown site. He and his business colleagues succeeded.70 The vote by the commission to decide on a location was as close as could be, 4 to 3 in favor of the downtown site vs. Bloomington.71 The original bill had stipulated that the occupants — the Twins and the Vikings — had to sign 30-year leases. Griffith balked at this. So in 1979 the commission working on lease agreements with the Vikings and Twins modified Griffith’s contract to allow him to vacate the lease if during a three-year period the average annual attendance was below the lesser of 1.4 million or the average attendance for the American league.72 There followed a number of legal challenges, but in the end the courts backed the plan and the stadium project proceeded.73

There was a lot about the Metrodome that was unfavorable for the Twins. It was designed primarily for the Vikings. The baseball field would be nestled in a corner of the structure, with seats facing away from the diamond, so that many spectators would have to crane their necks to see the infield action. Only about 8,000 seats were in the lower deck between first base and third base, not ideal for the sale of baseball tickets. In contrast to The Met, the Vikings were in the driver’s seat about revenue. The Vikings would control the sale of luxury boxes. They would get the majority of concession income, though they offered the Twins better terms than the Twins had offered to them at The Met. Business leaders even had to raise funds to pay for Griffith’s offices in the Metrodome because he didn’t have money given the Twins’ poor attendance in the ’70s as well as the emergence of free agency.74 All of this led to Griffith’s obstinacy about the terms of the lease.

The Minnesota Twins played in the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome from 1982 through 2009. (COURTESY OF THE MINNESOTA TWINS)

Construction of the Metrodome began in December of 1979, and under the brilliant leadership of Donald Poss, it was built on time and under budget.75 The original superstructure was finished in 1981, and in June of that year the construction of the roof began. The roof had to be weatherproof, coated by Teflon, and inflated by 20 large fans. It was inflated for the first time in October of 1981, raising the center of the dome 186 feet above the playing surface.76 When the ballpark opened in April of 1982, it could seat up to 55,000 for baseball and 63,000 for football. Both the Vikings and the University of Minnesota Gophers used the field for football. The first season there was no air-conditioning in the ballpark, and the midsummer games were unbearable. Air-conditioning was added for the 1983 season.

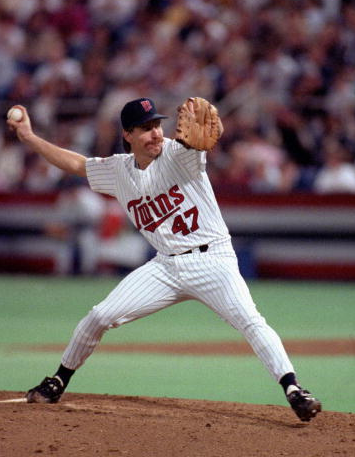

The Metrodome was a terrible place to play baseball. The ceiling led players to lose sight of popups and fly balls during night games, leading to the installation of upward pointing lights toward the roof, which helped some.77 The springy artificial turf led balls to bounce over outfielders’ heads. A popup by Dave Kingman of Oakland in May of 1984 disappeared through a vent in the ceiling. He was credited with a ground-rule double. And the roof collapsed several times due to weather. Even before it opened, it collapsed from the weight of snow in November 1981. During the 1983 season this happened again when the California Angels were scheduled to play the Twins. In April of 1986 a severe windstorm ripped a hole in the roof, showering fans in the right-field stands with water. The game was delayed.78 And later, when the Twins had success in the World Series in 1987 and 1991, the noise levels inside became unbearable. Twins players wore earplugs in defense.

The Twins were not very good in these early years of the Metrodome, and attendance was poor. In 1982 they drew only 921,186, and in 1983 only 858,939. It was clear to the city fathers that Griffith’s escape clause was about to be enacted. So for the 1984 season, the local business community organized a ticket buyout program. They bought unused tickets for many games, mostly midweek when the prices were lower. Their efforts to distribute them were not very successful. For example, a May game against the Toronto Blue Jays had a listed attendance of 26,761, but fewer than 10,000 people were actually there. The next day, the paid attendance was 51,863, but again, fewer than 10,000 fans were in attendance. When the Twins began listing both actual attendance and tickets sold, a court fight ensued about which would be the official figure that determined whether Griffith could exercise his escape clause. But before the issue could be resolved, he sold the team to a local banker, Carl Pohlad.79

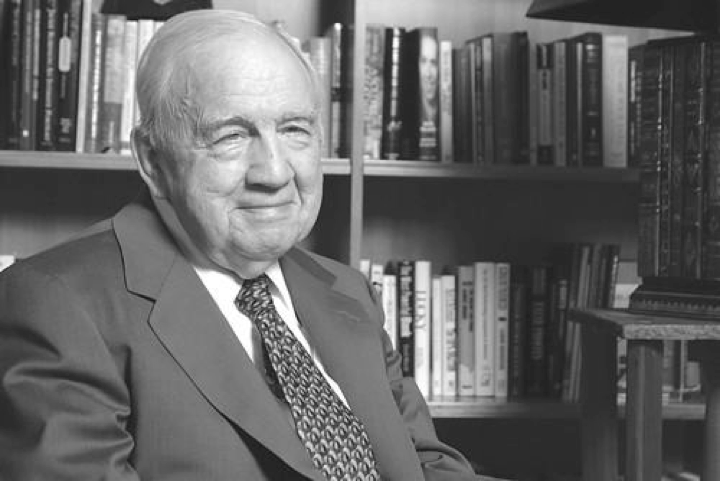

Who was Carl Pohlad? He could not have been more different than Calvin Griffith. Pohlad, like Griffith, had humble beginnings. Born in rural Iowa, he was a self-made businessman. While he was a good-enough high-school football player to earn an athletic scholarship to Gonzaga University, he left the university before graduating, and returned to Iowa to pursue a career in banking. He served in Europe during World War II, earning three Purple Hearts and two Bronze Stars.80 He and his brother-in-law initially had a business that helped banks manage their affairs. This led ultimately to their gaining control of Marquette National Bank in Minneapolis. The bank was profitable enough to allow Pohlad and his wife to move to the tony suburb of Edina. By 1955 he was president of the bank. He became very active in the banking industry, and established himself as a maker of deals that led to repeated profitable partnerships. In many of Pohlad’s business deals he pushed the limits and consorted with dubious partners.81 By the time negotiations for a new ballpark were reaching a frenzy, Pohlad’s reputation in the Twin Cities was tarnished, to say the least. Pohlad was interested in owning a major-league team, and had explored options for a variety of other teams before purchasing the Twins.82 He liked the publicity associated with team ownership.

Who was Carl Pohlad? He could not have been more different than Calvin Griffith. Pohlad, like Griffith, had humble beginnings. Born in rural Iowa, he was a self-made businessman. While he was a good-enough high-school football player to earn an athletic scholarship to Gonzaga University, he left the university before graduating, and returned to Iowa to pursue a career in banking. He served in Europe during World War II, earning three Purple Hearts and two Bronze Stars.80 He and his brother-in-law initially had a business that helped banks manage their affairs. This led ultimately to their gaining control of Marquette National Bank in Minneapolis. The bank was profitable enough to allow Pohlad and his wife to move to the tony suburb of Edina. By 1955 he was president of the bank. He became very active in the banking industry, and established himself as a maker of deals that led to repeated profitable partnerships. In many of Pohlad’s business deals he pushed the limits and consorted with dubious partners.81 By the time negotiations for a new ballpark were reaching a frenzy, Pohlad’s reputation in the Twin Cities was tarnished, to say the least. Pohlad was interested in owning a major-league team, and had explored options for a variety of other teams before purchasing the Twins.82 He liked the publicity associated with team ownership.

Pohlad was a more typical owner for his time. He did not depend on the Twins for his income. Griffith had explored several sales options, but decided in the end to sell to Pohlad because it was the first serious offer he got that met his terms. (Earlier in the year Donald Trump had approached Griffith about buying the team, but that exchange went nowhere.) A Minneapolis-based group led by Marv Wolfenson and Harvey Ratner offered $27 million in cash, but Griffith turned them down.83 There were complexities in the buyout, because at this time Griffith family owned just 52 percent of the team, and this was split in half with his sister, Thelma Haynes.84 The other 48 percent was owned by H. Gabriel Murphy of Tampa, a carryover from the Senators era.85 While Pohlad was able to buy the Griffths’ shares over time for $24 million, Murphy wanted his total share upfront. He got it, and Pohlad had 100 percent ownership of the team.86

Unlike Griffith, Pohlad was not a hands-on owner. He hired people who would manage the day-to-day operations of the club, including contract negotiations, trades, and other matters. But he did understand the business side of baseball ownership. He knew that a favorable stadium deal was a key to the profitability of a team. Even as he purchased the team from Griffith, he pushed for a better deal at the Metrodome. He got a better deal for concession revenue and more favorable rental terms, and kept the terms of Griffith’s escape clause.87

It’s ironic that several of the most successful years of the Twins franchise occurred in the midst of Pohlad’s negotiations and threats. The Twins won their first World Series in 1987, and repeated in 1991. In 1988 the Twins became the first American League franchise to draw over 3 million fans. This was helped by a late-season campaign to buy out tickets organized by a local radio station when it became clear that the 3-million mark was within reach. It’s ironic that the Twins, who would later face a possible contraction, achieved this attendance landmark before such American League juggernauts as the Yankees and Red Sox. It was later legitimately exceeded by the Twins during the first two years in Target Field, 2010 and 2011.

It’s ironic that several of the most successful years of the Twins franchise occurred in the midst of Pohlad’s negotiations and threats. The Twins won their first World Series in 1987, and repeated in 1991. In 1988 the Twins became the first American League franchise to draw over 3 million fans. This was helped by a late-season campaign to buy out tickets organized by a local radio station when it became clear that the 3-million mark was within reach. It’s ironic that the Twins, who would later face a possible contraction, achieved this attendance landmark before such American League juggernauts as the Yankees and Red Sox. It was later legitimately exceeded by the Twins during the first two years in Target Field, 2010 and 2011.

Despite success on the field, Pohlad continually used threats to move the team out of Minnesota to leverage a local movement to build a new ballpark. After the 1987 season he threatened to use his escape clause after the 1988 season unless a new lease was in place for the 1989 season. As Jay Weiner points out, a lot of the subsequent negotiations involved creative accounting on Pohlad’s behalf.88 He claimed huge losses. Despite skepticism by the Sports Facilities Commission, in 1988 Pohlad received a new 10-year lease with substantial improvements for the franchise. The lease included no rent at all, higher concession revenues, the right to sell advertising in the Metrodome, and a much more favorable escape clause. And while the Metrodome was originally built for the Vikings, the football team now had a much less favorable deal than the Twins, leading to ongoing enmity between the two franchises.

The 1990s and beyond were occupied by Pohlad’s push to get a new ballpark. There were two distinct phases, one that ended in a disastrous defeat and a second that led to the financing of what became Target Field. The Twins on the field were not very good after the 1991 World Series championship, and Pohlad complained about losing money. This in large part drove the push for a new stadium. By the mid ’90s, attendance had fallen to close to the 1 million mark, a figure that in the salary market of that era was not sufficient to sustain the team’s finances.

Much of the national enthusiasm for building new ballparks was inspired by Baltimore’s Camden Yards, which opened in 1992. While it was brand-new and had all the amenities of the times, it had a retro look to its baseball-specific design that was very appealing. Following Camden Yards’ opening, new retro-style ballparks were built in no fewer than 15 major-league cities. Pohlad himself visited Jacobs Field in Cleveland not long after it opened, and declared, “This is what I need.”89

The first major push for stadium financing began shortly thereafter, in July of 1994. Pohlad had designs on a ballpark with a retractable roof on a site along the Mississippi River not too far from the Metrodome. Public sentiment was running strongly against any public financing of a new stadium. It was not a good time for such an initiative in Minnesota.90 Not long before, in 1993, the North Stars NHL team had moved to Dallas. The new Timberwolves had overreached and built a new arena, the Target Center, that had to be bailed out by the City of Minneapolis and the State of Minnesota. Then the 1994 baseball season itself was a disaster: Not long after Pohlad announced his intention to seek a new ballpark, a players strike led to the cancellation of the rest of the season, including the World Series. It also didn’t help that a number of well-paid athletes for the Vikings and Timberwolves were having run-ins with the law. The citizens of Minnesota were in a foul mood concerning public support of professional teams.

All of this came to a head in the 1996-97 time frame. Governor Arne Carlson was eager to work out a deal between Pohlad and the state legislature that would enable the construction of a new baseball stadium. His stated goal was to get the legislature to pass a supporting bill during the 1997 session. However, he regretted his approach. He later said, “The vision and public buy-in should have come before the financing and the politics.”91 But it didn’t work that way. What at first looked like a good deal turned into a public-relations disaster. It appeared that Pohlad had committed $82.5 million of his own money to the ballpark’s proposed $350 million cost. In return, the state would get a 49 percent interest in the ballclub for coming up with the remaining money. But the details of the alleged agreement were murky, and when tough questions about the deal began to be asked, it turned out that Pohlad’s offer was really a loan that would have to be paid back. In the climate of the time, there could not have been a bigger blunder. When the vote came up in the legislature, it failed. As Jerry Bell, who oversaw the team’s new-ballpark effort, said, “It was the biggest mistake in all of the 13 years.”92 (The 13-year time noted by Bell was the total time from Pohlad’s 1994 announcement to the breaking of ground for Target Field in 2007.)

It was not long after this that the Twins threatened to move to North Carolina. A group led by businessman Don Beaver was eager to bring major-league baseball to the Greensboro area. Pohlad made an agreement to move the Twins if a stadium referendum could be passed in the Greensboro area. In May of 1998 Greensboro voters rejected the plan, and the prospect of a move was off.93

The situation for the Twins was not good. Steve Berg, in his account of the origins of Target Field, reviewed the situation in 1999:94 The Twins were in the midst of a prolonged series of losing seasons, and were 29th of the 30 major-league teams in attendance, 30th in payroll, and 30th in wins. Their revenues from ballpark income and broadcasting contracts were 29th in the league, “ten times lower than the Yankees’ revenues and four times lower than the major league average.” The memories of drawing more than 3 million fans and winning two World Series were very distant. All this happened when other cities were enjoying new ballparks while Twins fans were still dealing with the baseball-poor Metrodome.

Then St. Paul re-entered the picture. Its mayor, Norm Coleman, made an attempt to solve the Twins’ problem. He had already lured the NHL back to Minnesota by landing the Wild and, with the state’s help, was building them a new arena, the Xcel Energy Center, in downtown St. Paul. Five different sites in St. Paul were explored for a new ballpark; one near the intersections of Interstates 35E and 94 emerged as the favorite. But these plans lost their drive when the voters of St. Paul refused to approve a sales-tax hike that would have paid for a third of the cost.95

While all of this was going on, Major League Baseball, at the initiative of Commissioner Bud Selig, explored reducing the leagues by two teams. Just after the 2001 World Series, the owners voted 28 to 2 (the 2 being the targets of this reduction) to eliminate two teams. Cal Pohlad’s son Jim wrote to Twins employees that the team was willing to consider contraction due to “a feeling of hopelessness.”96 The landlords of the Metrodome took the issue to court, arguing that the Twins were still bound by a lease to play in the Metrodome. Hennepin County District Judge Harry Crump blocked any move to shut down the Twins franchise. His ruling was upheld in the Court of Appeals. This whole process came to be known as “Homer Hankie Jurisprudence.”97 Jerry Bell, the Twins president, later said he doubted Pohlad would have accepted the $250 million contraction offer if it had been legal.98 However, Pohlad continued to threaten to move the team, and another court decision that freed the Twins from their Metrodome lease after 2006 led to the series of actions resulting in a new ballpark for the Twins.

As the twenty-first century began, two important things happened. First, the Twins’ long streak of dismal performances ended. They made a strong showing in 2001, and in 2002 decisively won the Central Division, defeated the Oakland A’s in the Division Series, and lost to the eventual World Series champion Anaheim Angels in the American League Championship Series. The second development was that attendance at Twins games surged, starting with the 2001 season. The Twins had a raft of emerging stars, and were an exciting team. All of this rejuvenated the search for a new ballpark.

A series of downtown locations were put forward as possible ballpark sites. The original riverfront site was gone, having been committed to the construction of a new Guthrie Theater. One idea was to either update or replace the Metrodome. But a favored site emerged in the Warehouse District, pushed by two Minneapolis businessmen, Bruce Lambrecht and Rich Pogin. And a different approach was taken. Rather than focus first on the Twins’ needs, the group looked at the effect a ballpark would have on the community. As the Warehouse District site was small, the model the planners took was Wrigley Field in Chicago, which was fit into a tight space and was a centerpiece for the surrounding community, known as Wrigleyville. Lambrecht and Pogin dubbed their idea Twinsville. This site had a number of other advantages. It was near highways, light rail, and bicycle paths, making access easy. There were already substantial amounts of parking in the area, in part because the Timberwolves’ Target Center was nearby. There were many nearby hotel rooms, and the area was emerging as an entertainment district with restaurants, bars, and shops.99

The group formed an organization called New Ballpark Inc. When their initial plans to raise private funding didn’t go anywhere, they approached Hennepin County (Minneapolis and suburbs) as a potential partner. Two county commissioners, Mike Opat and Peter McLaughlin, had taken leadership roles in engaging the county in a wide range of issues. Under Opat’s leadership, the proposal for stadium development was taken to the state legislature. Somewhat oddly, the legislature approved in principle such a move, but excluded Hennepin County from the legislation, pointing instead to St. Paul. However, this move failed to take into account the rich transportation infrastructure in the Warehouse District site and the lack of it in the preferred St. Paul site near the Excel Energy Center. The idea of a St. Paul site died again.

Next came a complex, improbable, even heart-stopping series of events that led to final approval of a new ballpark. One key player was the new governor of Minnesota, Tim Pawlenty. Though he had not supported the Twins’ efforts in the past, his political instincts led him to explore what could be done if indeed Hennepin County played a key role in the financing. In April of 2005 the Twins and Hennepin County put forth a partnership plan for a ballpark. The Twins would pay one-third (really, this time), and the county would raise the rest through a sales-tax increase. In a contentious vote, four of the county commissioners voted to approve the tax hike. But then the question arose as to whether this tax hike should be approved through a voter referendum. Governor Pawlenty convened a meeting in October 2005 to put the matter up for a decision. The Twins wanted assurance from the leaders of both the House and the Senate that they would go ahead with a vote without a referendum requirement. The leaders agreed.100

On May 21, 2006, the bill passed in both houses of the legislature. But there was one final problem. The owners of the land on which the new ballpark would be built had offered the land for $12 million, but their offer had expired. Now they wanted more. The two sides were far apart, so the matter went to court, and a final settlement of $29 million was agreed to. The legislature had set a $90 million limit on the cost of the land and infrastructure needed (such as walkways, bridges, transit stations, etc.). With the big jump in the cost of the land, the Twins stepped in and offered an additional $24 million for these costs. The deal was finally done.

On May 21, 2007, ground was broken for construction of the new ballpark. An official ground-breaking ceremony was held on August 30, with a quite enfeebled Carl Pohlad turning over a spade of dirt. He would not see the field completed. He last visited the construction site on June 20, 2008, and died on January 5, 2009. By then his son, Jim Pohlad, had taken over the primary owner’s role of the Twins, though both of Carl’s brothers, Bill and Bob, serve on the team’s executive board. The Twins front-office directory lists the Carl R. Pohlad Family as the owners of the team.101 Dave St. Peter was president and chief executive officer.

The ballpark itself was designed by HOK, which in 2009 changed its name to Populous. The firm had designed many of the best of the new US sports venues, including NFL stadiums as well as baseball parks. Sixteen of the 21 new-generation ballparks were HOK-designed, including Camden Yards. Fitting the ballpark into the tight Warehouse District site presented numerous challenges. Steve Berg’s insightful account can be consulted for details of the design process.102 One of the key early decisions was to eschew a roof. Given the site, a roof would have added at least $130 million to the cost. When no extra funds were forthcoming, the idea was dropped. Big-league baseball in Minnesota would be played out of doors again, always. This was indeed the first time major-league baseball fans had been moved from a purely indoor facility to a purely outdoor one.103 Subsequent attendance figures showed that the fans loved being outdoors again.

The Minnesota Twins drew more than 3 million fans in the first two seasons at Target Field in 2010 and 2011. (COURTESY OF THE MINNESOTA TWINS)

Target Field opened for business in March of 2010, with a college baseball game between the University of Minnesota and Louisiana Tech, and 37,757 fans attended. The Twins played two exhibition games against the St. Louis Cardinals on April 2 and 3. The ballpark’s regular-season opener was against the Boston Red Sox on April 12, 2010, to a sellout crowd of 38,145. The Twins drew more than 3 million fans the first two years at Target Field, and only in 2016, when the Twins lost 103 games — a Twins franchise record — did attendance fall below 2 million. Unlike the Metrodome, the Twins controlled all the revenue at Target Field, and the lusty attendance figures gave them some operating room. On the field, they weren’t quite so fortunate. Their streak of nine winning seasons in 10 years ended in 2011. They had losing records from 2011 to 2014, then a surprising winning year in 2015 before having the worst record in their history in 2016. The Twins’ fortunes reversed in 2017, with a winning record and a wild-card playoff spot. (They lost again to their playoff nemesis, the Yankees, in the one-game wild-card playoff.)

During Calvin Griffith’s ownership of the Twins, they relied heavily on developing their own players through their farm system. While they did occasionally sign veteran players, most of their best-known players of that era were home-grown. But free agency changed that. While Griffith was not a buyer as free agency arrived, his lineups were often raided, and he also engaged in trades to forestall free-agency losses (e.g., Rod Carew). During Pohlad’s ownership, this changed somewhat. The better financial fortunes of the Twins, especially since the turn of the century, allowed them to make investments in the free-agent market. They never became a major player in the free-agent market, and as has so often happened, some of those signings worked, and others didn’t.

One of their more interesting moves came in March of 2010 when they signed Joe Mauer to an eight-year contract extension valued at $184 million, taking effect in 2011 and running through 2018, the largest contract in Twins history. While many fans greeted this move approvingly, as Mauer was clearly the face of the franchise during this era, others were concerned that this might limit their ability to sign other valuable players later. As with so many longer-term contracts with a somewhat older player, Mauer’s performance leveled off and declined slightly during the period of the contact, in part due to injuries. In 2018, after completing the last year of his contract, Mauer retired.

By 2017 the Twin Cities area had done something nobody back in the 1990s could have imagined. The Twins and the Vikings each had new, single-purpose ballparks. The Vikings built their new stadium on the site of the old Metrodome. The Minnesota Gophers football team, which had played in the Metrodome for many years, also had a new stadium, one that the Vikings played in while their new digs were under construction. The Twin Cities now had four professional franchises in relatively new facilities. Going forward, it’s not clear whether this will be a stable situation. As Jay Weiner has argued, the Twin Cities are an improbable market for hosting four major-league-caliber professional sports teams, not to mention major-league soccer, and major college sports (football, basketball, hockey).104 The mathematics of ticket sales, luxury boxes, and other fan-based costs are a stretch for a population the size of the Twin Cities metropolitan area.

It’s not immediately clear which of the four franchises is the most vulnerable. The Twins still struggle with the small-market issues that have plagued them throughout the post-free-agency era. If their farm system can keep delivering exciting young talent, they may be able to navigate their way through the challenges of their small-market status. But given all this, the Pohlad family is apparently uninterested in giving up ownership of the team.105

The Twins ownership history has several notable characteristics. First, in their 59-year history, they have had only two owners, Calvin Griffith and the Carl Pohlad family. Second, both ownerships were family-oriented, a bit more so for Griffith, who packed the front office with relatives. (The Pohlad family has stepped up following Carl’s death.) Third, the ownership history has focused on ballparks. The building of Metropolitan Stadium in Bloomington was essential for attracting the interest of both Horace Stoneham and Calvin Griffith, a lesson the Twin Cities learned from the experiences of other franchise moves in the 1950s. Then, with the Vikings in the lead, the focus shifted to improving or replacing Metropolitan Stadium; the result was the Metrodome. But the Twins, despite winning two World Series and breaking the 3-million mark in attendance at the Metrodome, lobbied for more than a decade to get what in the end was Target Field. Threats to move the franchise were used by both Griffith and Pohlad in their efforts to get a new venue, and baseball itself threatened the Twins with contraction, ironically saved by the courts via the stadium lease. Given the so-far-satisfying experience of the Twins at Target Field, it could be that the Twins face a period of contentment under the leadership of the Pohlad family.

Acknowledgements

A number of SABR colleagues read draft versions of this history. Andy McCue, the overall editor of this series, provided early and continuing feedback. Stew Thornley, Dan Levitt, and Lloyd Keppel read and commented on the entire draft. Rod Nelson provided helpful information about Billy Martin. Jay Weiner provided helpful input early in the process. Judy Olson provided valuable editorial feedback. I am grateful for all this help. Of course, any errors that remain are my fault.

Sources

Besides the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following:

Vince Gennaro, Diamond Dollars: The Economics of Winning in Baseball (Hingham, Massachusetts: Maple Street Press, 2017).

Bob Showers, The Twins at the Met (Edina, Minnesota: Beaver’s Pond Press, 2009).

Stew Thornley, Minnesota Twins: Hardball History on the Prairie (Charleston, South Carolina: History Press, 2014).

Notes

1 Jay Weiner, Ballpark Games: Fifty Years of Big League Greed and Bush League Boondoggles (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 3.

2 Weiner, 7.

3 Ibid.

4 Weiner, 9.

5 Wikipedia, “Midway Ballpark” (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Midway_Ballpark), viewed May 22, 2018.

6 D. Brackin and P. Reusse, Minnesota Twins: The Complete Illustrated History (Minneapolis: MVP Books, 2010), 10.

7 Weiner, 1-5.

8 Weiner, 12-15.

9 Weiner, 15.

10 Weiner, 24-5.

11 Weiner, 25.

12 Ibid.

13 Andy McCue, Mover and Shaker: Walter O’Malley, the Dodgers and Baseball’s Westward Expansion (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 143.

14 Weiner, 10.

15 Stew Thornley, personal communication.

16 Weiner, 11.

17 Walteromalley.com, March 23, 1957.

18 Ibid.

19 Weiner, 26.

20 Robert F. Garratt, Home Team: The Turbulent History of the San Francisco Giants (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2017), 21-24.

21 Garratt, 13-21.

22 Ibid.

23 Weiner, 27. Weiner also notes that this announcement triggered the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce to look into a new ballpark to replace Crosley Field.

24 Garratt, 20.

25 Weiner, 28.

26 Weiner, 29.

27 Weiner, 31.

28 Weiner, 30.

29 Ibid.

30 Weiner, 33.

31 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 544-556.

32 Weiner, 46.

33 Wikipedia, “Metropolitan Ballpark,” viewed May 24, 2018.

34 Lowenfish, 557-578.

35 Steve Berg, Target Field: The New Home of the Minnesota Twins (Minneapolis: MVP Books, 2010), 43. From 1987 to 2009 they used an “M” on the hat as their primary uniform. They reverted to the “TC” as primary in 2010, though the “M” was used as an alternative for a while.

36 Weiner, 53.

37 Jon Kerr, Calvin: Baseball’s Last Dinosaur (Minneapolis: Wisdom Editions, 2016, 2nd Edition), 97.

38 Shirley Povich, “Senators’ New President Started as Batboy,’ Sporting News, Nov. 9, 1955, 2.

39 Dan Levitt and Mark L. Armour, “The Last of the Family Owners: The Griffiths Build Their Lone Minnesota Pennant Winner,” in Gregory H. Wolf, ed., A Pennant for the Twin Cities: The 1965 Minnesota Twins (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2015), 16.

40 Levitt and Armour, 15-17.

41 Levitt and Armour, 19.

42 Bill Pennington, Billy Martin: Baseball’s Flawed Genius (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015), 150.

43 Pennington, 152.

44 Pennington, 154-55.

45 Pennington, 155.

46 Pennington, 156.

47 Pennington, 156-160.

48 Pennington, 160.

49 Pennington, 167-169.

50 Stew Thornley, Baseball in Minnesota: The Definitive History. Minneapolis: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2006), 196.

51 Thornley, 198.

52 Nick Coleman, “Griffith Spares Few Targets in Waseca Remarks,” Minneapolis Tribune, October 1, 1978.

53 Ibid.

54 Kerr, 172.

55 Details in Bill Madden, Steinbrenner: The Last Lion of Baseball (New York: HarperCollins, 2010).

56 Kerr.

57 Madden, 74.

58 Weiner, 64.

59 Weiner, 63.

60 Weiner, 61.

61 Weiner, 65.

62 Weiner, 67.

63 Stew Thornley, personal communication, June 19, 2918.

64 Weiner, 66-69.

65 Weiner, 74.

66 Amy Klobuchar, Uncovering the Dome (Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland Press, 1982, Reissued in 1986 with changes), 68-72.

67 Weiner, 77.

68 Klobuchar, 86-107.

69 Weiner, 79.

70 Weiner, 92.

71 Klobuchar, 106.

72 Klobuchar, 135-138.

73 Klobuchar, 138-141.

74 Weiner, 96.

75 Klobuchar, 141-144.

76 Thornley, Baseball in Minnesota, 224-5.

77 Thornley, personal communication, June 19, 2018.

78 Thornley, Baseball in Minnesota, 226-7.

79 Thornley, Baseball in Minnesota, 227.

80 Weiner, 119.

81 Minneapolis Star & Tribune, April 20, 1997, A1, A12, A13.

82 Minneapolis Star & Tribune, April 20, 1997, A13.

83 Weiner, 105-106.

84 New York Times obituary, October 12, 1995.

85 Washington Post obituary, November 4, 2001.

86 Weiner, 105-7.

87 Weiner, 127-8.

88 Weiner, 128-129.

89 Weiner, 189.

90 Berg, 49.

91 Berg, 49.

92 Berg, 50.

93 Berg, 52.

94 Ibid.

95 Berg, 54-59.

96 Berg, 59.

97 Berg, 60.

98 Ibid.

99 Berg, 62.

100 Berg, 64-67.

101 mlb.com/twins/team/front-office, opened March 28, 2019.

102 Berg, 74-125.

103 Berg, 98.

104 Weiner, 467-471.

105 twinkietown.com/2017/2/2/14471290/owner-jim-pohlad-family-not-selling-mlb-baseball-minnesota-twins-ever, Opened March 28, 2019.