Cleveland Guardians team ownership history

This article was written by David Bohmer

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

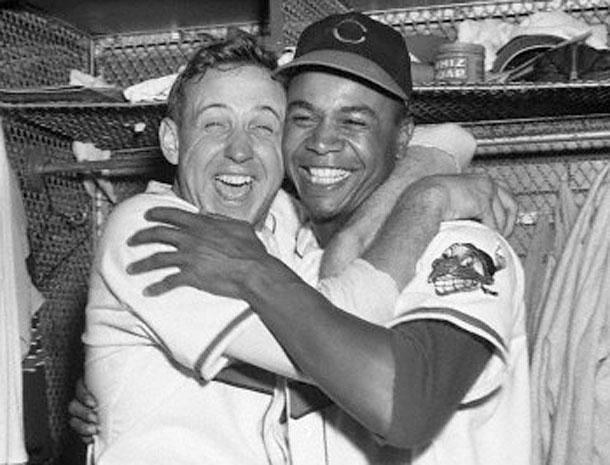

Steve Gromek, left and Larry Doby celebrate after Cleveland’s win in Game Four of the 1948 World Series. Cleveland would go on to win the championship in six games, and the franchise is still looking for its first World Series title since. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

Introduction

Cleveland had a history of major-league franchises long before the American League club now known as the Guardians was moved there in 1900.

The Cleveland Forest Citys were one of the original teams in the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players in 1871, though the club folded after the 1872 season. While not a part of the original National League, the Cleveland franchise was established in 1879 when the league expanded. The Blues were to last six years in the NL, folding after the 1884 season. A new franchise was established in the American Association in 1887, lasting two seasons and departing only two years before the Association itself ended. In 1890, two new franchises emerged in the Forest City, the Spiders name returning as a National League entry and the Infants representing the ill-fated Players League. The latter team, along with the league, lasted only one season. The Spiders were one of the better teams in the what now was a 12-team National League, finishing second three times and almost always ending up in the first division — until 1899. In possession of two NL franchises, the Spiders owners decided to strengthen the St. Louis team at the expense of Cleveland, causing the weakened club to finish with a 20-134 record — the worst in major-league baseball history. Not surprisingly, the team was one of four eliminated in the National League before the start of the 1900 season.

It was into this vacuum that Ban Johnson, president of the Western League, moved his Grand Rapids team to Cleveland in 1900. Johnson renamed his minor-league circuit the American League. That same year, he relocated his St. Paul franchise to Chicago, striking a deal with the owners of the NL Chicago club. His league was still “Western,” with franchises from Buffalo to Kansas City. The Chicago and Cleveland moves had not changed that regional designation, but they had placed in league in two of the seven largest cities in the country, foreshadowing Johnson’s intent to compete with the NL monopoly. A year later, he moved into four major Eastern markets and officially declared the Americans a major league, directly taking on its National counterpart.

The early positioning of the Cleveland and Chicago clubs did little to benefit those two original American League franchises, at least as far as long-term success was concerned. Of the eight initial teams, Cleveland has won the fewest World Series, only two. While the Chicago franchise has won three, only one of those successes has come in the last 90 years and Cleveland has actually appeared one more time in the Series (6) than has Chicago. They are, in that regard, the two least successful original American League clubs.

At the same time, Cleveland has had some notable accomplishments in its American League history. Twice the franchise has established major-league attendance records, first for a single season and later for consecutive sellouts. The fans have witnessed some of the game’s superstars, including Napoleon Lajoie, Shoeless Joe Jackson, Bob Feller, and Satchel Paige. Then known as the Indians, they were the first club to integrate the American League, in 1947. And later, Cleveland fans also witnessed one of the longest droughts — 35 years — during which the team was never in serious contention for the pennant. Over the history of the franchise, there have been 12 different owners or syndicates that have shaped the history — notable or not — of the American League baseball club in Cleveland.

Charles W. Somers, 1900-1915

Ban Johnson’s Chicago move positioned the league in the country’s second largest city, but it was the Cleveland relocation that proved to be far more instrumental to Johnson’s ultimate success in becoming an equal of the National League. Johnson initially approached Davis Hawley, who had been one of the local owners of the Spiders, to see if he had any interest in purchasing the Grand Rapid Rustlers and moving them to his city. Hawley declined interest but set up a meeting for Johnson with Charles Somers, owner of a large coal company, and Jack Kilfoyl, owner of a popular downtown men’s clothing store and a major investor in Cleveland-area real estate. That meeting not only secured Somers’ and Kilfoyl’s investment; it also led to the purchase of League Park, the last home of the Spiders, for $10,000.1 The new Cleveland team would not only have owners, but also a place to play ball, located at the end of an established streetcar line at the corner of Lexington Avenue and 66th Street on the east side.

Ban Johnson’s Chicago move positioned the league in the country’s second largest city, but it was the Cleveland relocation that proved to be far more instrumental to Johnson’s ultimate success in becoming an equal of the National League. Johnson initially approached Davis Hawley, who had been one of the local owners of the Spiders, to see if he had any interest in purchasing the Grand Rapid Rustlers and moving them to his city. Hawley declined interest but set up a meeting for Johnson with Charles Somers, owner of a large coal company, and Jack Kilfoyl, owner of a popular downtown men’s clothing store and a major investor in Cleveland-area real estate. That meeting not only secured Somers’ and Kilfoyl’s investment; it also led to the purchase of League Park, the last home of the Spiders, for $10,000.1 The new Cleveland team would not only have owners, but also a place to play ball, located at the end of an established streetcar line at the corner of Lexington Avenue and 66th Street on the east side.

Somers, born in Newark, Ohio, in 1868, quickly proved to be the more important partner. His family moved to Cleveland in 1884. His father owned a major coal-mining and -distribution company that Charles took over and grew.2

Even more instrumental to Johnson and his league, however, was the enthusiasm and financial support that Somers provided. Essentially, Somers helped to finance the move of Charles Comiskey’s team to Chicago. He also provided monetary support to Connie Mack’s team in Philadelphia when it was established in 1901 and was the primary investor in setting up the new franchise in Boston that same year. In fact, the early Boston club was called the “Somersets” after him, the local paper declaring that Somers “is amply able to finance a club here.”3 On his trip to Cleveland, Johnson had found someone “eager to throw his all into the fight to make the American League’s ambitious dreams become actual realities.” Somers put hundreds of thousands, likely well over a million, dollars at the league’s disposal.4 In fact, Johnson’s main biographer has concluded that if Somers “had not financed several of the clubs in the first few years, the loop’s history would have been brief.”5 In Charles Somers, Johnson had the gold mine that ensured the longevity of the American League. His move of a team to Cleveland proved far more beneficial than he had initially expected.

Ironically, Somers’ investments in other teams proved to be more fruitful than was his backing of the Cleveland club. In the first five years of the American League, from 1901 to 1905, Somers’ three major investments besides Cleveland — Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago — were the only pennant winners in the league. Cleveland during that period never finished higher than third place. That pattern was to hold true throughout Somers’ ownership of the club; the team came close only in the 1908 season when it finished a half-game game behind the Detroit Tigers. One can only wonder what might have been in 1908 had Somers agreed a year earlier to trade outfielder and future Hall of Famer Elmer Flick, near the end of his career, for a young Ty Cobb. The Cleveland magnate asserted after he had rejected the offer that “maybe (Flick) isn’t quite as good a batter as Cobb, but he’s much nicer to have on the team.”6 Further, had the club been able to make up a game that had been rained out that season, it may well have tied the Tigers and faced them in a playoff game. The club was a victim of now-defunct rules in the AL, along with Somers’ own reservations on Cobb.7

While Somers never had the success in Cleveland that he did with the other clubs he had financed, he did receive some early payback for his broader support. In 1902, in the midst of the battle between the NL and the still upstart AL, Napoleon Lajoie jumped from the NL’s Philadelphia Phillies to the Athletics. A Pennsylvania judge banned Lajoie from playing any games for the A’s in that state, which would have caused him to miss half the season. To prevent that, Johnson transferred Lajoie to the Cleveland club, with little compensation in return, so he would only have to miss the 11 games the team played in Pennsylvania.8 The deal would give Cleveland its first player inducted into the Hall of Fame and its manager for part of his tenure in Cleveland, as well as the longest continuous club nickname — the Naps — until they were renamed the Indians after Lajoie was sold.

In fact, it was during Somers’ ownership that that club had been given all six of its nicknames, the last one, Indians, enduring until the present. When the team first arrived from Grand Rapids, the sportswriters referred to it as the Lake Shores, perhaps reflecting the city’s proximity to Lake Erie. The name was somewhat ironic since the actual ballpark was more than a mile from the lake. They then became the Bluebirds in 1901, for their blue uniforms, quickly shortened to the Blues, perhaps reflecting the nickname given to the original National League club from 1879-1884. The name was again changed in 1902 to the Broncos, for no apparent reason, until the writers again changed it to the Naps in 1904, playing off the first name of their star second baseman. After Somers sold Lajoie, the writers came up with the Indians, perhaps remembering and honoring Louis Sockalexis, the first Native American to play in the major leagues (Spiders, late 1890s.)9 It’s equally possible both writers and front office thought the name presented a more warrior-like image. In either case, they have remained the Indians since.

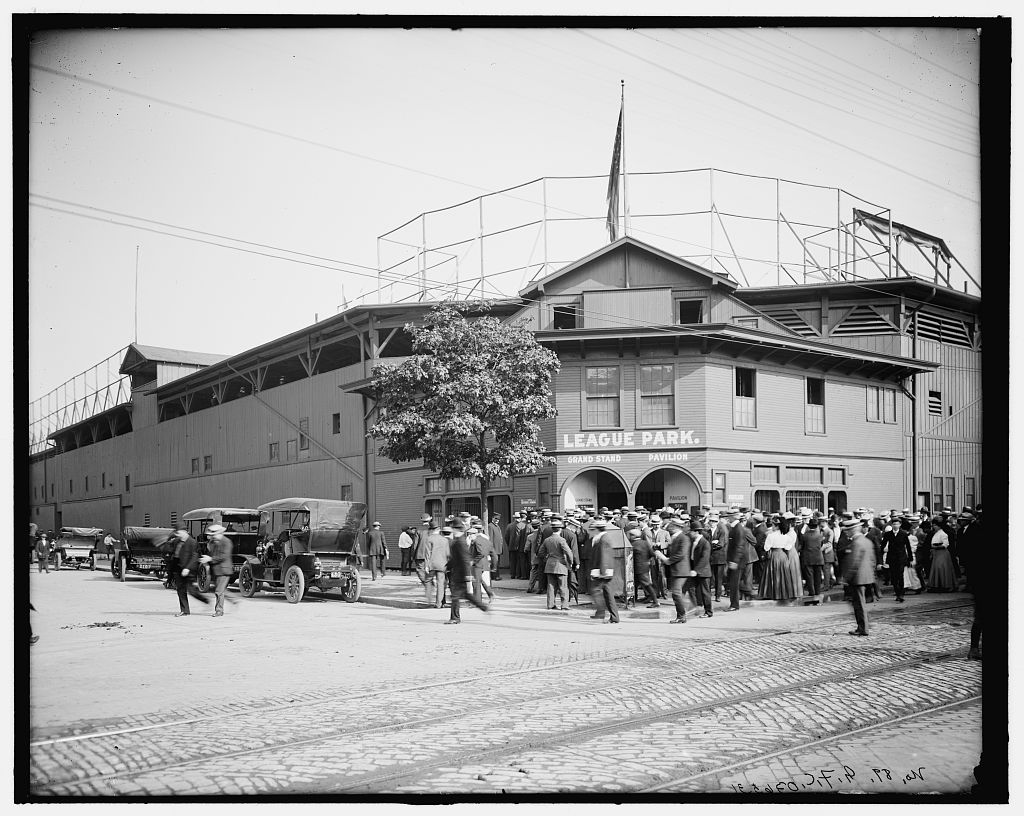

While Somers did not have any involvement with any of the team’s nicknames, he was instrumental in upgrading the ballpark he had purchased in 1900. League Park was built for the NL Spiders in 1890 and, as was common at the time, wood was used for much of the edifice, including its support beams. Such ballparks were fire hazards. Between the 1909 and 1910 season, League Park was essentially rebuilt, using concrete and steel in place of the wooden beams and other supports. The dimensions of the old park, with its unique contours, were largely maintained. The new park had a seating capacity of 19,200, although up to 20,000 could be accommodated with standing-room areas. Ernest S. Barnard, at the time secretary/treasurer of the Naps and much later the president of the American League, played a major role in renovating the park.10 The new structure was, from all indications, financed entirely by Somers. It would remain the primary home of the ballclub for another 36 years.

Somers was solely responsible for that financing largely because Jack Kilfoyl decided to sell his interest in the ballclub. There is no evidence to indicate that the new ballpark precipitated the departure, but the timing would suggest that the added cost may have been a factor in his decision. Whatever the reason, Somers bought out Kilfoyl’s interest around the time the construction began and later named Barnard the club’s vice president, perhaps rewarding him for his efforts and success in overseeing the renovation of the ballpark.11

Along with the renovation, the 1910 season also saw the arrival of one of Cleveland’s best-known players. Joseph Jefferson Jackson — Shoeless Joe — was traded by the Athletics to Cleveland in midseason, after two failed efforts on his part to make the club in Philadelphia. Having rejected the deal for baseball’s greatest hitter in 1907, Somers now brought to the Naps the player who would produce the third highest batting average of all time. In his first full season in Cleveland, 1911, Jackson batted .408, the best average of his career. He quickly became an idol of fans during his five-year tenure with the Naps.12

Jackson’s success and fan admiration, however, could not alone produce a successful team, let alone help Somers’ other business investments. After a competitive season in 1913 in which the team drew a record 500,000-plus fans, last-place and seventh-place finishes in 1914 and 1915 brought fewer than 200,000 to League Park in each of those years. A wealthy Charles Somers could have readily survived the struggling ballclub, but his coal-delivery business was in serious decline as more Cleveland homes converted to electricity. He attempted to maneuver out of the situation by selling some of his players, including dealing Jackson to the White Sox for $31,500.13 But that did little to offset Somers’ financial woes, with his business debts now estimated to be as large as $2 million.14 He was forced to turn to Ban Johnson for assistance in selling the ballclub.

While Somers was never successful in producing a Cleveland pennant winner, he was instrumental in the survival of the American League. His money had enabled the establishment of franchises in Chicago, Boston, and Philadelphia. He was even able to help fund the creation of a franchise in New York, the Highlanders, in 1903. Chicago, Boston, and Philadelphia all won pennants quickly. For whatever reason, perhaps because Somers was too much a micromanager, his own club never produced such results.15 At the same time, beyond ensuring the success of the American League through his money, he also helped negotiate the National Agreement, which brought peace to major-league baseball in 1903, and served for most of his ownership as a vice president of the league.16 While he may have been too much of a micromanager to produce a winning ballclub in his hometown, his macro involvement, especially his money, unquestionably enabled the American League to survive and prosper. Somers lived into the 1930s. He recovered some of his wealth. When he died at his summer home on a Lake Erie island in June of 1934, during the thick of the Great Depression, he was worth over $2 million. He remained a fan of the Indians, witnessing their first championship in 1920 and following them until his death.17

James C. “Sunny Jim” Dunn, 1916-1927

Somers’ need to sell the Cleveland club in late 1915 came at a convenient time for Ban Johnson. For a variety of reasons, the Federal League folded at the end of the 1915 season. The owners of the eight clubs in the “outlaw” league were all prospective buyers of major-league teams, if available, and at least two besides the Indians — the Cubs and the Browns — were purchased by Federal League magnates. Supposedly the owners of the Pittsburgh Rebels were interested in purchasing the Indians, but along with a Cleveland group they were rejected in their effort to acquire the team.18 Instead, Johnson chose to award the franchise to a fellow Chicago businessman already well known to him, Jim Dunn. The deal did not go through until March, but was completed before the start of the 1916 season.

Somers’ need to sell the Cleveland club in late 1915 came at a convenient time for Ban Johnson. For a variety of reasons, the Federal League folded at the end of the 1915 season. The owners of the eight clubs in the “outlaw” league were all prospective buyers of major-league teams, if available, and at least two besides the Indians — the Cubs and the Browns — were purchased by Federal League magnates. Supposedly the owners of the Pittsburgh Rebels were interested in purchasing the Indians, but along with a Cleveland group they were rejected in their effort to acquire the team.18 Instead, Johnson chose to award the franchise to a fellow Chicago businessman already well known to him, Jim Dunn. The deal did not go through until March, but was completed before the start of the 1916 season.

There is no record to indicate why Johnson rejected both the local offer and that from a Federal League owner, especially since the offers from Charles Weeghman and Philip Ball to buy the Cubs and Browns were accepted. Johnson was at the time in some difficulty with some of the magnates after he negotiated the deal to end the Federal League, largely because it would cost the 16 owners collectively hundreds of thousands to buy out the league’s investors. Perhaps he rejected the first two offers because he could not be assured of support from the potential buyers that he had received from Somers, not so much financially as in the assurance that they would back his decisions. It was clear that some of Johnson’s strength was beginning to erode after the Federal League deal. Awarding the franchise to Dunn, a close friend, would ensure that Johnson had another owner as supportive as Somers had been. According to The Sporting News, Dunn also seemed suited for the job. “He is a big person, physically and mentally, and his disposition can best be indicated by the fact that he likes to have everyone call him Jim.” That informality, while notable, was probably the least important reason for the turnaround Dunn generated with the team.19

Dunn had made his money in the railroad construction business. A native of Marshalltown, Iowa, he had moved to Chicago to take advantage of the larger opportunities afforded by the booming city.20 Even with his personal wealth, he either could not afford or would not pay the Indians’ price tag of $500,000 by himself. After bringing in other Chicago businessmen, Dunn was still dependent upon $100,000 loans from both Johnson and Charles Comiskey.21 Those loans would cause some problems later, especially during the Carl Mays controversy, but did not in any way impede the operation of the franchise, which Dunn quickly rebuilt and promoted, largely making the decisions on his own.

One of Dunn’s earliest moves was to rehire most of the front-office staff and meet personally with Charles Somers for his input, assuring a smooth transition. Somers was certainly impressed. He gave his support to Dunn, calling him “a real live wire (who) will … give Cleveland a good ball club.”22 His most significant early move was the acquisition of Tris Speaker, star center fielder for the Boston Red Sox. The deal was expensive, costing the Indians two players, including a solid pitcher, as well as $55,000 in cash. Dunn asserted: “A tail-ender will not pay in Cleveland, but a first division team will draw big. … I would not have thought of entering baseball if I had intended to be content with a second division outfit.”23 It is likely the deal was motivated in part to replace the loss of local hero Shoeless Joe in a salary-dump trade by Somers in late 1915. During his first season in Cleveland, Speaker led the league in hits, doubles, and batting average. While it did not move the team up much in the standings — the Indians finished in sixth place — his overall efforts did restore fan interest. With the acquisition, Dunn claimed that “the purchase of Speaker will, I believe, show fans that I am making good on my promise to give them a good ball club.”24 He clearly succeeded. Dunn more than tripled attendance from the previous season with his efforts at rebuilding and marketing the ballclub.

The team continued to improve during the next two seasons, finishing third in 1917 and second in 1918. The latter season was plagued by the entry of the United States into World War I. Some players were lost to the draft and others were seeking jobs in war-related industries to avoid being sent to the front lines. Dunn became one of the first advocates among the owners of ending the 1918 season early, believing that with the loss of players he could not give Cleveland fans the brand of baseball they deserved.25 Both leagues did agree, under pressure from the federal government, to end the season early, beginning the World Series soon after Labor Day. Dunn demonstrated his concern for his players by giving them notice of the decision before it was officially announced so they could quickly move to find war-related jobs.26 A drop in attendance during the season may also have encouraged Dunn to advocate its early end, though the team still fared better than it had during the last two years of the Somers regime.

While the 1919 season started late, again due to the war, the Indians drew over 500,000 for only the second time in its history and again finished in second place. While the team was profitable, Dunn had yet to deliver on his early promise of a championship in Cleveland. During the season manager Lee Fohl was fired and was replaced by Speaker. Equally notable during the season was the Carl Mays issue, which demonstrated, more than a year before the Black Sox scandal became public, the extent of the rift between American League owners.

Carl Mays, who had helped the Red Sox win the World Series in 1918, was dissatisfied and asked to be traded. Boston obliged with a late July 1919 deal with the Yankees. At the time, Mays had been suspended from baseball by Ban Johnson, who for that reason attempted to block the deal. He was supported by five of the AL owners, including Dunn. However, the league’s Executive Committee that year was made up of Dunn and the three owners who now opposed Johnson and his control over baseball. Those three, Charles Comiskey of the White Sox, Harry Frazee of the Red Sox, and Jacob Ruppert of the Yankees, overruled the league president and allowed Mays to return to baseball and report to the Yankees.27 It was the first time Johnson had been rejected on a major decision, but Dunn, by his support, had provided the payback Johnson had hoped for when he recruited him to purchase the Indians. The fact that Johnson still held stock in the club sullied Dunn’s backing and may have hampered his effectiveness with the other owners for the rest of his time in baseball.28

There was a further irony to the Mays deal during the 1920 season when the Indians met the Yankees in New York in August. Mays was the pitcher and Ray Chapman the batter when an errant pitch struck Chapman in the temple. He died later that evening, the only fatality caused directly by an incident during a major-league game. Dunn must have wondered at the time how history might have been different had the majority of AL owners had had their way on the Mays trade to New York. That wasn’t the only somber event of the season. Ace pitcher Stan Coveleski’s wife died earlier in the year, producing what was unquestionably a remorseful year for the organization.29

In spite of those tragedies, 1920 also proved to be the season Dunn had promised Cleveland fans when he purchased the club, delivering its first pennant, followed by a World Series championship. The club finished two games ahead of the White Sox and three ahead of the Yankees in a close pennant race, largely aided by the exposure and suspension for the last week of the season of seven White Sox players accused of fixing the 1919 World Series. When the Indians clinched the pennant, Dunn sought and quickly gained approval to flip the games in the Series. The first three of the best-of-nine Series were supposed to be played in Cleveland, as well as the final two if necessary. Instead, Dunn requested that the Series open in Brooklyn so he would have time to add more good seats in League Park.30 The risky move paid off, both in success on the field and at the box office. After losing two of the first three games in Brooklyn, Cleveland won the last four to win the Series in seven games. In a ballpark that usually accommodated 20,000 fans, the Indians drew over 107,000 for the four games in Cleveland.31 A crowning touch was provided before the players scattered after the final game. Dunn signed each of them to a 1921 contact, providing all with a 10 percent increase over the previous season’s salary.32

That generosity was not out of character for Dunn. He was an unusual magnate in the way he cultivated relations with his players. As Henry Edwards, a sportswriter for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, observed, “Jim Dunn does not regard his players as employees. They are his boys, his pals. Neither do the players regard Dunn merely as an employer. To them, he is … their colleague.”33 When Dunn died, Smoky Joe Wood, one of his players, referred to him as “the brightest man who was ever owner of a baseball club … a great man.”34 That level of praise from a player toward an owner was and even now remains relatively uncommon.

There was little time for Dunn to bask in the glory of the Series results, however. The Black Sox Scandal brought demands from many magnates to restructure the game, particularly at its top, as a way to bring gambling under control. Major emphasis was placed on naming an independent commissioner who would not be tied to either league or to the owners in any fashion. The most popular proposal, the Lasker Plan, essentially created an independent commissioner. Ban Johnson was adamantly opposed to the plan and Dunn remained one of five AL owners loyal to Johnson until outside pressure as well as internal strife forced Johnson to agree to the appointment of Kenesaw Mountain Landis as commissioner.35 Dunn was likely not happy with the result, but it did prevent the possible breakup of the American League, and the 1921 season was thus guaranteed to begin as usual.

League Park in Cleveland, circa 1910s. (DETROIT PUBLISHING COMPANY, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

The 1921 season was another good one for Cleveland. The team was only four games off its 1920 performance and League Park, now named Dunn Park, drew almost 750,000 fans.36 That did not match the 900,000-plus fans of the season before and the team’s performance was not good enough to prevent the beginning of the first Yankees dynasty, featuring Babe Ruth in his second year in New York. Cleveland finished second, 4½ games removed from another pennant.

The 1921 season was also Dunn’s last full one as owner of the Indians. He fell ill with influenza shortly after the 1922 season started and succumbed on June 9. His will left the team to his widow, Edith. She thus became one of the rare women who owned a baseball team of any kind, although she had virtually no involvement in the day-to-day operation of the club. That responsibility fell to Ernest Barnard, whom Dunn had named president of the team in his will. Speaker remained manager until an alleged gambling scandal that also involved Ty Cobb forced his departure from the team in 1927. The club reached as high as second only once after Dunn’s death and finished in the second division three times. The major reason for the decline in performance was that money to invest in players and marketing was less plentiful after Dunn’s death. His estate was far less willing to provide resources to the club than Dunn himself had been. When Edith Dunn remarried, the team was put up for sale after the 1927 season and was purchased by a Cleveland syndicate headed by Alva Bradley.37

It is, of course, difficult to surmise how well the Indians would have done had Dunn not died. He was obviously successful at promoting baseball to the city of Cleveland, not the least because he was able and willing to invest in player talent. Overall, Somers’ teams had played just under .500 baseball and managed only one season as high as second place. Dunn’s squads produced a .545 percentage, finished second four times and won a pennant and World Series. His teams averaged 550,000 fans a year — a 76 percent increase over Somers’ clubs. The 912,000 fans who crossed through the turnstiles in 1920 remained an attendance record until Bill Veeck purchased the team. Part of that success certainly seemed to stem from Dunn’s relationship with his players. It’s clear they liked playing for Dunn and probably were more committed to the team’s success as a result. It’s also clear that although Dunn was part of a syndicate, he had full control over his ballclub, on matters of both personnel and finances. As we will see with future owners, especially Alva Bradley, that did not always happen. Dunn may have been an outsider to Cleveland, but he brought a level of success to the ballclub that fans wouldn’t see again for more than two decades.

Alva Bradley II, 1928-1946

Cleveland fans had reason for optimism in 1928. The sale of the Indians was consummated and the new owners prepared for the coming season. After the death of Jim Dunn, the team had languished under the ownership of his estate. There was little new investment and the results, only one second-place finish, demonstrated that lack of support. Even worse, popular manager Tris Speaker had resigned and then was forced to leave the team. The sixth-place finish in 1927 seemed to show how far removed the glory days of 1920 were.

The new syndicate that purchased the Indians for $1 million, however, gave reason for the city to be optimistic. Unlike Dunn’s group, all of the partners were Clevelanders with deep business interests in the city. Alva Bradley, whose investments included banking, real estate, and transportation, quickly emerged as the leading partner. The other major investors included Alva’s brother, Charles, along with bankers Joseph Krause and John Sherwin.38 Bradley gave more reason for encouragement by stating that his group “believed that a winning baseball team was a big asset to the development of a city.” He added that the syndicate would “make every endeavor to put (the team) into the winning class.”39 There was good reason to take Bradley’s words at face value since the syndicate was thought to be the wealthiest owner group in the American League.40 Before the year ended, Bradley named Billy Evans as vice president of the team. For many years Evans had been an umpire in the American League and was, Bradley declared, “one of the best-informed baseball men in the business.”41 Bradley also indicated that the club would establish a farm system, a new trend in the major leagues, looking seriously at New Orleans and Terre Haute as locations and also inviting offers from other cities.42

Finally, there was serious talk in the city about building a new ballpark, far larger than League Park, which came to fruition in November of 1928 when the proposal received strong approval in a referendum. While often thought to have been an effort to attract the Olympics, in fact it was part of a major effort to upgrade Cleveland’s lakefront.43 Even though the 1928 team fared worse than the year before, there was reason for fans to be upbeat. The reality with the syndicate, however, proved to be considerably different than those expectations.

Although the 1929 season, which produced a much improved third-place finish, gave further reason for optimism, the onset of the Depression in October would prove to be a major setback. Members of the syndicate no longer had the extensive wealth they had possessed when they purchased the Indians, and became far more conservative in their willingness or ability to put money in the club. The partners’ reactions were reinforced by a decline in attendance from 1931 through 1935, even though the Indians continued to finish in the first division. Even the new ballpark failed to generate much additional fan interest during the depths of the Depression.

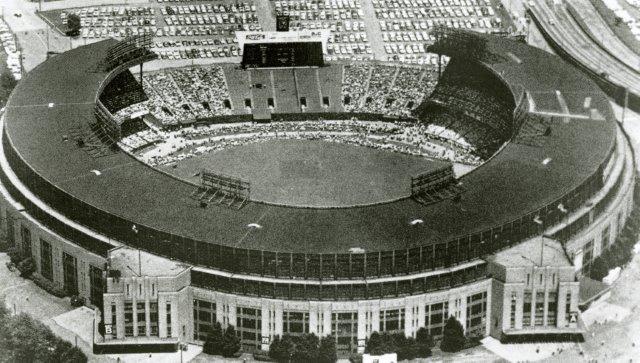

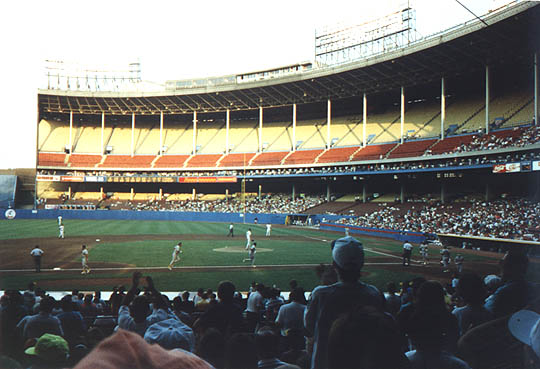

Municipal Stadium in Cleveland opened in 1932; a crowd of more than 80,000 watched the Indians’ first game there on July 31. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

The new ballpark, in fact, would prove to be an ongoing issue, at times even an albatross, for as long as the syndicate owned the team. Troubles began even before the ballpark, capable of seating over 80,000, was finished in 1931.44 Plans had been made and tickets sold for a gala opening in July, but all of that came to a screeching halt when the city and the club were unable to reach a deal on a lease. Bradley expressed his frustration in The Sporting News, saying, “[W]e have made one concession after another to the city, until now we come to the point where we can go no further.” The club had to refund $20,000 received from the advance sale of tickets for the grand opening.45 The Sporting News followed two weeks later with an editorial stating, “Now we have the spectacle of the city of Cleveland turning down a good offer from a responsible tenant that would reflect credit on the city and give it a permanent and profitable revenue.”46 As negotiations dragged on well into 1932, Bradley demonstrated further frustration by saying negotiations had been hampered “by the fact that too many city officials have the power to disrupt the result of weeks of careful thought and business-like dealings.”47 A deal was finally reached with the city and the new stadium opened to a crowd of more than 80,000 on July 31, 1932, a year after originally planned. Fans witnessed a 1-0 loss to the Athletics in a pitching duel between Lefty Grove and Mel Harder.48

That explosion of fans was short-lived, and even with the cavernous ballpark and the massive turnout for the opening game, the club failed to achieve the previous year’s attendance for the season. That caused Bradley to reconsider using Municipal Stadium at all. The Indians still owned League Park and paid no rent for any games played there. They began to play all their games at League Park in 1935, with the exception of the All-Star Game, which drew over 65,000 fans at Municipal Stadium.49 Otherwise, the new ballpark sat vacant for the baseball season.

In spite of the All-Star Game draw, 1935 was another bad year financially for the Indians. For the third year in a row, attendance fell under 400,000, even though the team finished in the first division in each season. General manager Billy Evans resigned after having his salary cut twice, a decision that was made not by Bradley but by his syndicate partners.50 Shortly after Evans’s departure, Bradley indicated that in the eight years he had been president of the Indians, the team had lost a total of $241,000.51

As the losses continued, the club began to play more games at Municipal Stadium, even with its obvious shortcomings: rental cost, fewer home runs and a lack of intimacy. The center-field fence was almost 500 feet away and, with extensive foul territory, fans were further removed from the playing field.52 In spite of those drawbacks, Bradley began to increase the number of games played at Municipal Stadium during the rest of his tenure. Opening Day, with its huge crowd, was a natural, as were Sundays and holidays. Bradley was also one of the first in the AL to receive approval for night games, so the seven allowed were also played there. No lights were installed at League Park. By the 1940s, close to half of the season schedule was played at the larger park.53 Only with the arrival of Bill Veeck, however, was League Park rendered obsolete.

On the issue of night games, Bradley proved to be a pioneer in the American League, though he was hardly a pacesetter in that regard for major-league baseball overall. As late as 1935 both Bradley and Evans declared that there would never be night baseball in Cleveland since there was already too much competition in the evening.54 The success of night baseball for Ohio’s other major-league club, Cincinnati, apparently caused Bradley to reassess his thinking, and he petitioned the other owners at the winter meetings in 1937 to allow the team to play seven games under the lights. They rejected his request by 5 to 2, with Clark Griffith of the Washington Senators leading the opposition, claiming there was “no emergency financial status” demonstrated and thus no reason to allow such games. The Tribe president was bitter over the refusal.55 He was not deterred, however, coming back the next year at the owners’ meeting and getting approval for seven night games in 1939. The club had to incur the cost of installing lights at Municipal Stadium, but the investment paid dividends for the first game, when 55,000 fans came to witness the new feature.56 In spite of that huge crowd, however, attendance overall declined for the 1939 season, ending up almost 100,000 lower than in 1938, even though the team finished in third place in both seasons.

Night baseball was not the only area when Bradley spoke in favor of innovation. In 1933 William Veeck Sr., then president of the Chicago Cubs, came out strongly in favor of interleague play, largely as a way to increase fan interest and attendance during the height of the Depression. Bradley gave Veeck strong support on the American League side. Like Veeck in the National League, however, both were in the minority.57 Implementation of interleague play was still more than five decades away.

While Bradley was somewhat progressive on lights and interleague play, he was totally the opposite on radio broadcasts and the development of a farm system. As early as 1931, when many clubs were experimenting with broadcasts as a means of increasing fan interest, Bradley was adamantly opposed, even though he charged for broadcasting rights. In effect, he was rejecting another potential revenue source.58 When Bill Veeck Jr. purchased the Indians during the 1946 season, there were still no radio broadcasts of Indian games in Northern Ohio.59 Bradley was also reluctant to build a farm system. Even though he claimed to have spent $128,000 on the minors, new talent, and scouting in 1938, he was actually lobbying Commissioner Landis, whom he strongly supported, to eliminate the farm system. When Landis decided not to abolish major-league team control of minor-league clubs, Bradley negotiated an agreement with Baltimore for the 1942 season. However, the lack of such arrangements earlier with lower-level teams was and would continue to be detrimental to the ballclub.60 It cannot be determined, of course, how much better Cleveland might have been with a richer farm system, or how much more interest radio might have generated, but there is little doubt that both decisions were detrimental to the team before the club was sold.

Even without a farm system, however, Bradley was responsible for two highly significant player signings that shaped the team’s history in important ways. Bob Feller was signed in 1936 and made his major-league debut that year at age 17. He proved to be a sensation, striking out 17 batters in his last game before returning for his senior year in high school in Iowa. Perhaps he was too successful, for other teams questioned whether his signing was legitimate and appealed to Landis to nullify his contract. If the commissioner had followed the pattern on other rulings he had made, Feller could have readily been declared a free agent. Instead, thanks in part to a direct appeal by Feller’s father, Landis allowed him to remain with the Indians and instead fined the club $7,500. In the aftermath, Bradley asserted, “Our rights to his services probably never would have been challenged if we had kept him in the minors instead of rushing him straight to the big leagues.”61 The other significant player move came as an indirect byproduct of the 1940 team revolt, which led to the firing of the manager at the end of the season. After an interim manager for a year, Bradley named Lou Boudreau, age 24, the player-manager. Boudreau had signed with the Indians out of college and had played three full seasons when he became the youngest manager in baseball history.62 He grew to be very popular with Cleveland fans, and as of 2018 remained the last manager to win a World Series for the Indians.

As mentioned, the major event leading to Boudreau’s hiring was the player revolt of 1940. During the 19 years of Bradley’s tenure, 1940 was the only year the Indians came close to winning the pennant. Oscar Vitt had managed the team for two full seasons before and there already were rumblings among some players who felt he was autocratic and uncaring. Bradley, although aware of the complaints, didn’t take them too seriously until well into the 1940 season, when things came to a head. On June 16, the majority of players, including Mel Harder and Feller, presented Bradley with a petition demanding that Vitt be fired immediately. The petition stated that “Vitt ridiculed them publicly … that he had been insincere in his dealings with them … that his words and actions in the dugout were of such a nature that the manager’s own jitters were transferred to the players, making it impossible to play their best ball.” Even Vitt admitted that he may have been too severe with the team.63 Bradley persuaded the players to rescind the petition, and the season continued, albeit with considerable friction. The Indians stayed in contention, but fell off near the end of the season, leading one sportswriter to refer to the players as “crybabies” and criticizing Bradley for interfering and undermining his manager.64 The team finished a game out of first and Vitt was fired in October. It was generally thought that Bradley had overstepped his bounds with the players and that as a result the revolt had cost the team a pennant.

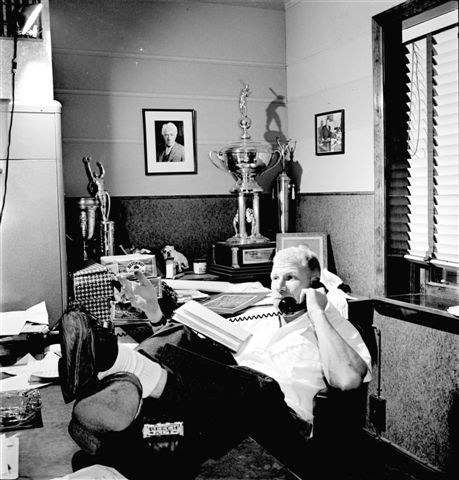

Cleveland Indians star Bob Feller, center, signs his 1941 contract as general manager Cy Slapnicka, left, and owner Alva Bradley look on. It would be Feller’s last contract until he returned from military service in World War II four years later. (CLEVELAND PRESS COLLECTION, CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY)

Shortly after the 1941 season ended, Bradley faced his next major challenge. Just days after Boudreau had been named manager, the bombing of Pearl Harbor plunged the country into World War II. Bradley’s first response was to organize an all-star game during the coming season between major leaguers already in the service and the winner of the annual All-Star Game. The event drew over 62,000, with all proceeds going to assist the war effort. It was perhaps small consolation to a club that would have one of the lowest attendance levels during the 1942 season. Beyond attracting fans, Bradley was also challenged with keeping enough players to maintain a team. To do so, he encouraged them to seek war-related jobs during the offseason, to keep them from being drafted. As the war continued and the number of talented players decreased even further, he advocated that the ballparks be padlocked for the remainder of the war rather than sell “below standard baseball.”65 While Bradley made his views known publicly, he never pushed his idea at the annual meeting in December and it’s likely it would not have been well received had he done so.

For the most part, in fact, Bradley was not a major force in the major-league meetings. Often attorney Joseph Hostettler, a minor partner, was the main spokesman for the club. Bradley did play one very important role during his years in baseball, however, in the selection of a replacement for Landis after his sudden death in November 1944. Bradley was one of four owners named to the search committee, joining Don Barnes of the Browns, Phil Wrigley of the Cubs, and Sam Breadon of the Cardinals. Bradley and Barnes were strongly opposed to Ford Frick, the National League president, who initially had been considered the leading candidate to replace Landis. They were joined by Wrigley in preferring to hire an outsider. Bradley chaired the session that offered the name of US Senator Albert Benjamin “Happy” Chandler but made no official recommendation to the full meeting of the magnates on who should be chosen.66 The owners did, in fact, select Chandler as the new commissioner.

Bradley’s involvement with the naming of Chandler was the zenith of his tenure with Cleveland. The team continued to languish, finishing in the second division in 1945 and heading for the same the next year. Attendance was lackluster. Rumors of a sale had been floating around since early 1944, but Bradley denied them. They grew stronger in June of 1946, when one article even mentioned Bill Veeck Jr. as the buyer. Bradley again denied the rumors, even giving detailed reasons why such a deal would never happen.67 In fact, a number of owners in the ownership syndicate, especially John and Francis Sherwin, the largest investors and sons of an original partner, had grown tired of cash calls to keep the team afloat, along with little, if any, expectation of profits. Bradley was the only partner who still remained from the original syndicate. Many of the newer members had limited interest, if any, in baseball as a business and thus were less willing to pour more of their money into the team. As a consequence, Bradley was one of the last to learn that a group led by Veeck was buying the Indians. The deal was closed on June 22, 1946, for $1,539,000, only a short time after Bradley had learned about it.68 There wasn’t even time for him to form a group to purchase the club on his own.

The fans of Cleveland, and much of the baseball world for that matter, were excited by the deal, as was usually the case when a new buyer emerged for a weak club. Ed McAuley of the Cleveland News summarized the reaction succinctly in The Sporting News: “The former owners and stockholders were conservative, calm, patient and backwards when it came to innovations in the game. (Veeck) is the direct contrast — a glad hander, a congenial guy, an extrovert who has what the people would term ‘the common touch’!’” In the same issue of The Sporting News, J.G. Taylor Spink, the editor, summed up the change by saying: “It may be expected that the hitherto sedate club by the shores of Lake Erie will undergo quite a face lifting. … Veeck hadn’t been in charge two hours before the customers had accepted him unreservedly as a bright hope for better days. … The A.L (with) its lack of showboat tactics and the offering of baseball as 100% of its daily attraction, is due for a seasoning with tabasco.”69 Cleveland fans did not have to be patient this time. They would immediately witness a new and very different era of leadership in running the club. The tabasco seasoning would begin!

By almost any standard, Alva Bradley’s tenure with the Indians would be considered at best a mediocre one. Only a single second-place finish, numerous managers until Boudreau, a lack of publicity, including no broadcast of games, and lackluster attendance were the main characteristics of his time overseeing the club. The team did play better than .500 ball under his ownership, but attendance averaged 50,000 a season below that of the Dunn era. Born in February 1884, Bradley was, for the most part, a fairly typical businessman of his generation — somewhat aloof, leaning to the status quo, not wanting to make waves. He lived a fairly typical lifestyle of the well-to-do — golf, tennis, bridge, and horseback riding, reflecting his upbringing as well as his Ivy League education at Cornell. His wealth had come from coal and real estate, not from owning the Indians. He was generally hesitant to innovate. He also wanted deeply to be liked, even being known to fire his managers on “the friendliest of terms.”70 Even had he been more innovative, he may well have been hampered by a syndicate that tightly controlled the financial side of the business, in which he had little input. Bradley may have lacked imagination, but he also had limited access to the resources needed to innovate during the Depression and World War II, a problem that was not unique to the Indians. After the sale, he rarely attended a baseball game, even though he remained a fan of the Indians. He died in Delray Beach, Florida, in 1953.71

Bill Veeck Jr., 1946-1949

The new owner of the Indians was a hurricane compared with the previous management, as The Sporting News had forecast. In what J.G. Taylor Spink referred to as “a stiff workout — or a talk with Bill Veeck,” the new Cleveland owner summed up his philosophy: “Baseball has to be promoted, it has to be sold. …” As Ed McAuley summed up in the same issue, the Indians were “sadly in need of the hypodermic needle with which Veeck and his associates have stabbed it.”72 It was, indeed, to be a true shot in the arm for Cleveland baseball fans. Born in Chicago in February 1914, Veeck had grown up around baseball as his father was president of the Chicago Cubs until his death in 1933. His son spent countless hours at the ballpark, doing numerous jobs. Between his experience at Wrigley and his ownership of the Milwaukee minor-league team in the early 1940s, Veeck had gained considerable experience in building and promoting a ballclub.

The new owner of the Indians was a hurricane compared with the previous management, as The Sporting News had forecast. In what J.G. Taylor Spink referred to as “a stiff workout — or a talk with Bill Veeck,” the new Cleveland owner summed up his philosophy: “Baseball has to be promoted, it has to be sold. …” As Ed McAuley summed up in the same issue, the Indians were “sadly in need of the hypodermic needle with which Veeck and his associates have stabbed it.”72 It was, indeed, to be a true shot in the arm for Cleveland baseball fans. Born in Chicago in February 1914, Veeck had grown up around baseball as his father was president of the Chicago Cubs until his death in 1933. His son spent countless hours at the ballpark, doing numerous jobs. Between his experience at Wrigley and his ownership of the Milwaukee minor-league team in the early 1940s, Veeck had gained considerable experience in building and promoting a ballclub.

Veeck undertook numerous strategies to draw fans to the ballpark. Promotions were a huge part of it. He immediately signed a contract with a local radio station to broadcast all home and away games. He re-established Ladies Day on a regular basis. He purchased new uniforms for 150 ushers and raised the number of night games to 21 from 14. He talked with cab drivers and bartenders, both of whom he would frequently encounter, to get a sense of what was wrong with the team. He carried that over to games, at which he mingled with fans to get their sense of how to improve the experience while watching the teams play. One of his early promotions was a highly publicized event to honor trainer Lefty Weisman, who had been with the Indians for 25 years. To add entertainment and comedy to the experience of the game itself, he hired Max Patkin as a coach and Jackie Price as a player. While both knew baseball, they were far better known as comedians. When not playing, which was most of the time, Price would entertain fans between innings with numerous bat and ball tricks. Patkin, while coaching, would go through a variety of gyrations, once even getting on the nerves of Red Sox manager Joe Cronin. Veeck’s efforts paid huge dividends. While the 1946 team finished in sixth place, it drew over a million fans, breaking the attendance record set by the 1920 pennant winners.73 At the time Veeck took control of the team in June, it had drawn 289,000 fans. For the remainder of the season, a little over half of the remaining 77 home games, his promotions brought in almost 800,000.74

Veeck almost got in the way of his efforts, however. Rumors began shortly after his syndicate gained ownership that the new magnate was looking to remove Boudreau as manager at the end of the season. Veeck later claimed to have Casey Stengel waiting in the wings to take over as soon as Boudreau was removed or traded.75 Local sportswriters responded with a highly publicized campaign to keep the popular manager, drumming up huge support from fans and forcing Veeck to back down from any managerial change. He concluded that “Lou was so popular that if I traded him away, I would have the whole city down my neck.”76 Instead, the owner hosted a night for Boudreau, drawing another large crowd and rewarding the manager with a raise and a new contract that would carry through the 1948 season.77 In the end, Boudreau remained as manager of the Indians longer than Veeck owned the team.

While both Price and Patkin had proved to be part of the attraction at home games, neither would return in 1947. A small part of the problem was that Price was a shortstop like Boudreau, though he certainly was no competition for the future Hall of Famer. The larger issue came in spring training in 1947, the club’s first year in the new Tucson, Arizona, facility, chosen so Veeck could be close to his ranch and family during that time. On a train with the rest of the team, Price walked through a car where a number of women were seated, carrying a number of snakes. The obviously disturbed women complained to the conductor, who was told by the Indians’ players, intending a practical joke, that it was Boudreau who was carrying the snakes. The accused manager had to explain his way out of the mess, which he did not find particularly humorous. He turned on Price and Patkin, exclaiming that he “was hired to manage a ball team and not a circus.”78 At the manager’s insistence, there would be no more appearances in Cleveland of either entertainer. But Veeck quickly found other ways to attract the fans.

Among his many tactics, Veeck became his own personal speaker’s bureau. He traveled to any community in Ohio, Pennsylvania, or New York considered in the Indians drawing area to speak. Veeck estimated that he gave up to 500 such speeches a year.79 While that number seems unlikely, he also added little gimmicks to make his appearances even bigger draws. At a Jaycee meeting in Ashland, Ohio, where he was to speak, the required uniform for admission was a sport shirt like the ones Veeck wore.80 He also found other ways to make the games more attractive to fans in outlying communities. The Indians now played all of their home games in cavernous Municipal Stadium with its exceptionally deep outfield stands. Recognizing that fans wanted more home runs, he installed temporary fences to bring the home-run distance closer to that of other major-league ballparks, shortening much of the outfield by up to 70 feet.81 He continued his special attractions, the most notable a celebration of Cy Young’s 80th birthday on June 11, at which Young’s entire community of Newcomerstown, Ohio — population 4,564 — was hosted for free.82 With all of his efforts, Veeck was well on his way to increasing attendance in 1947 by almost 50 percent, smashing the record set the previous year.

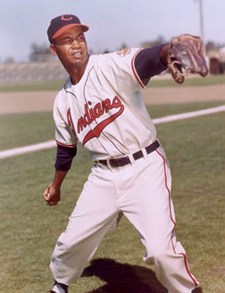

Veeck had another major promotional trick up his sleeve in 1947, although he denied it was such, and subsequent years would demonstrate that it was far more than a short-term stunt. After watching both the success of Jackie Robinson with the Dodgers and noting the larger crowds that Brooklyn was drawing both at home and on the road, Veeck signed Larry Doby to a contract, paying Effa Manley’s Newark Negro League club $5,000. Doby became the first black player in the American League. Veeck told The Sporting News that “Robinson has proved to be a real big leaguer, so I wanted to get the best Negro boy while the getting was good.” He added, “I am operating under the belief that the war advanced us in regard to racial tolerance.”83 Veeck also asserted that Doby was signed to build a stronger, pennant-contending team, not as a publicity stunt.84 Unlike Rickey with Robinson, Veeck had done nothing to prepare either Doby or his teammates for his arrival. While Doby’s first season in the majors was not successful, he was still generally well received by the club. His biographer has attributed that largely to Boudreau, the coaches, the players, and traveling secretary Spud Goldstein rather than to the owner.85 In any case, the American League was now integrated like the National. That unquestionably also helped draw fans to the ballpark in 1947.

Veeck had another major promotional trick up his sleeve in 1947, although he denied it was such, and subsequent years would demonstrate that it was far more than a short-term stunt. After watching both the success of Jackie Robinson with the Dodgers and noting the larger crowds that Brooklyn was drawing both at home and on the road, Veeck signed Larry Doby to a contract, paying Effa Manley’s Newark Negro League club $5,000. Doby became the first black player in the American League. Veeck told The Sporting News that “Robinson has proved to be a real big leaguer, so I wanted to get the best Negro boy while the getting was good.” He added, “I am operating under the belief that the war advanced us in regard to racial tolerance.”83 Veeck also asserted that Doby was signed to build a stronger, pennant-contending team, not as a publicity stunt.84 Unlike Rickey with Robinson, Veeck had done nothing to prepare either Doby or his teammates for his arrival. While Doby’s first season in the majors was not successful, he was still generally well received by the club. His biographer has attributed that largely to Boudreau, the coaches, the players, and traveling secretary Spud Goldstein rather than to the owner.85 In any case, the American League was now integrated like the National. That unquestionably also helped draw fans to the ballpark in 1947.

Veeck was encouraged when Doby got off to a strong start in 1948 and by July, with the team in the thick of a pennant race, he made a roster change that garnered even more publicity. Satchel Paige, the best known pitcher in the Negro Leagues, was signed in July, when Veeck became convinced the club had a chance to win the pennant.86 The signing was costly, totaling $55,000, of which $25,000 went to Paige, $15,000 to the Kansas City Monarchs, and $15,000 to Abe Saperstein, with whom Veeck had contracted to help recruit black talent.87 The signing was not well received by sportswriters. Dan Daniel claimed Paige was already 50 and he found little excitement in New York about the pitcher joining the majors.88 Spink was even more vocal in his editorial, stating, “To sign a hurler at Paige’s age is to demean the standards of baseball in the big circuits. Further complicating the situation is the suspicion that if Satchell were white, he would not have drawn a second thought from Veeck. Will Harridge … would have been well within his rights if he refused to approve the Paige contract.”89

Paige quickly proved the skeptics wrong. He was hardly a travesty who generated little interest or failed to help the team. The Indians won the pennant in 1948, winning a tiebreaking game with the Red Sox. They were unquestionably helped by Paige’s 6-1 record, mostly as a starting pitcher. He drew huge crowds at home and on the road when he pitched, including more than 72,000 in Washington who came to see him win a game.90 Paige’s performances and his draw as a gate attraction prompted Veeck to telegraph J.G. Taylor Spink with his response to the earlier editorial: “Paige pitching — no runs, three hits. Definitely in line for TSN rookie of the year award.”91 Paige did not become rookie of the year, but he certainly made a major impact on the Indians and baseball in his rookie season.

While Paige, at 42 not 50, was near the end of his career, Doby was just beginning. And their success prompted Veeck to recruit even more black ballplayers. By the end of the next season, Veeck had 14 such players under contract, scattered throughout the minors.92 They included Minnie Miñoso, Al Smith, and Luke Easter, two of whom contributed directly to the success of the Indians in the 1950s. The aggressive signing of black talent was one of the ways Veeck laid the groundwork for the continued success of the team on the field long after he sold the Indians after the 1949 season.

Along with the aggressive effort to bring in new talent, Veeck also fortified both the minor-league organizations controlled by the team and the scouting of prospective players. He signed affiliation contracts with Triple-A San Diego and Double-A Oklahoma City.93 San Diego was especially important since it provided a city where the newly signed black players would not face the racial issues encountered in many Southern communities.

Veeck also brought in new front-office management that would help the Indians well after he sold the team. Hank Greenberg was ready to retire from his Hall of Fame career after one season with the Pirates in 1947. Cleveland’s owner offered Greenberg $50,000 to play and $25,000 to coach.94 The former star opted for the latter, thinking his playing days were over, but instead of coaching, he became an assistant to Veeck, enabling him to learn the front-office side of the business. After the 1948 season ended with the club’s second World Series win, Veeck put him in charge of the team’s minor-league system. At the time, the team had 16 minor-league teams and over 400 players in the system.95 It would be a natural transition for Greenberg to become the club’s general manager after Veeck departed, a job he would end up holding through the 1957 season.

While Greenberg would prove to be successful as the Indians’ general manager, he would be no match for Veeck’s ability to relate to the players. Perhaps that simply reflected Veeck’s generosity. He negotiated attendance-related contracts with Bob Feller, making him close to the highest-paid player in the majors, if not the highest.96 By 1949, the club had the highest player payroll in baseball, perhaps reflecting its success both on the field and at the ticket office.97 Years later, Veeck acknowledged that he preferred to be generous with his players, saying, “I would just as soon give a player what he thinks he deserves if I can afford it.”98 Clearly, he could afford it with the Indians. He also added a personal touch, often spending time in the dugout after games and giving out bonuses when players were signed. He was even known to give newly acquired players cash so they could purchase new suits.99 Larry Doby went so far to call Veeck “the greatest humanitarian that I have ever known,” adding, “The man wasn’t a hypocrite. He didn’t have one set of values in the church and another outside the church.”100 Many of his players would have agreed with Doby’s assessment.

The largess of the Tribe’s owner did not carry over to the 1949 season’s outcome, however, at least not in terms of the team’s ability to again make it to the World Series. For a variety of reasons, the team could finish no better than third. That did not stop Veeck, always looking for publicity, from capitalizing on the team’s decline in performance. When the Indians were mathematically eliminated from the pennant race, he promoted the next home game as a wake. The 1948 Series pennant was placed in a casket and driven in a hearse around Municipal Stadium by Veeck. The casket was then buried beyond the left-field fence.101 Ironically, the event would also serve to symbolize the end of the owner’s time with the Indians. The writing on the wall came even before the 1949 season had started, when Veeck’s first wife, Eleanor, filed for divorce in February.102 It is unclear how quickly Veeck realized he needed to sell his interest in the team to achieve a settlement, but he announced the sale in late October.103 The ultimate sale would return the club to local ownership, but without the continuous fanfare that had been generated by Veeck during his 3½ years in the city. Veeck would prove to be a very tough act to follow.

His achievements were certainly not limited to the ball field. Many of his promotions went beyond luring fans in to watch games. Some were actual fundraisers meant to benefit the community. He made a deal with Branch Rickey to have the Indians and Dodgers play two exhibition games during the 1948 season, one in each city, with the proceeds going to the sandlot baseball programs in both towns. In late July, Veeck presented a check for almost $80,000 to the Cleveland Baseball Federation from the game played in Municipal Stadium.104 Once the club had passed a record 2.5 million in attendance in 1948, Veeck announced that the take from the last home game of the season would be donated to the Community Chest, the forerunner of the United Way. It raised over $55,000 for the agency, which was right in the middle of its campaign.105 Nor were his fundraisers limited to organizations. During the championship season, Don Black, one of the team’s starting pitchers, collapsed on the mound, stricken with a brain hemorrhage that hospitalized him for weeks and ended his baseball career. Veeck held a night in honor of the recovering pitcher and awarded his family over $40,000 in proceeds from the gate.106 The citizens of Cleveland, as well as the Indians players, were true beneficiaries of Veeck’s promotions.

So was the front office of the club. The finances of any privately held baseball club are difficult to obtain, but there were enough hints provided from the time of Veeck’s tenure to obtain a general sense of the profitability or the organization. An article in The Sporting News in early 1948 indicated that the team needed to draw a million fans at home to break even. The article then mentioned that the club had 782 people on its payroll: 179 ticket takers,187 ushers, 132 special police, 20 office workers, 5 dining room employees, 117 scorecard boys, 28 scouts, 58 players and 56 ground crew.107 A later issue reported that the club made a profit of $1.5 million in 1947 when the team drew 1,521,978 paid admissions.108 Since the team drew over 2.6 million in 1948 and over 2.2 million in 1949, it is reasonable to assume both years were also extraordinarily profitable, even with normal increases in expenses. As an example of costs, the 1948 payroll was announced to be $400,000 for player salaries.109 At the same time, Veeck announced that profits from the first season and a half he had owned the club had already paid off his investment.110 It is likely the Indians were baseball’s best-performing club financially during Veeck’s tenure, even with his generosity to players and to local charities. Unlike with the previous syndicate, there were no cash calls during the entire period Veeck owned the team, not surprising given the owner’s ability to draw crowds to the Stadium.

The club was sold by Veeck for $2.2 million to a Cleveland syndicate headed by Ellis W. Ryan, CEO of the W.F. Ryan insurance company. Veeck and his Chicago partners sold their interest, but some Cleveland members of the earlier syndicate, including comedian Bob Hope, had maintained their partial ownership in the club. Veeck netted $700,000 before taxes and it’s fair to assume the other investors profited equally as well from the deal.111 The magnate summed up his success both operationally and financially by saying, “My philosophy as a baseball operator … is to create the greatest enjoyment for the greatest number of people … draw people to the park and make fans out of them.”112 He certainly succeeded during his short stay in Cleveland.

The Indians were certainly not Veeck’s last baseball endeavor. He remarried and purchased the St. Louis Browns in 1951, continuing to conduct outrageous promotions in an attempt to revive the franchise. He later twice owned the White Sox, again making a name with his innovations and ways to bring fans to the ballpark. He died in Chicago on January 2, 1986, less than five years after selling the White Sox for the second time. He is the only major owner of the Indians to be inducted in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Ellis W. Ryan, 1950-1952

Ellis Ryan was certainly not a Bill Veeck. In public, Ryan was always immaculately dressed. Veeck wouldn’t be caught dead in a suit. Veeck loved to take part in the many promotions he used to bring fans to the ballpark. Ryan was less enthralled with promotions and always remained behind the scenes when they were done. Most importantly, Veeck grew up around baseball, his father having been the president of the Chicago Cubs for two decades. He had also operated a very successful minor-league franchise in Milwaukee before purchasing the Indians in 1946. Ryan, on the other hand, was a casual baseball fan, his expertise and money coming from the insurance business. He had actually been more involved with football and hockey in Cleveland than he had baseball before heading the group that purchased the Indians.113 His lack of background in the sport empowered Hank Greenberg, giving him more latitude to run baseball operations. While he was no longer officially a vice president in the new regime, Greenberg was named general manager and was given basic control over the day-to-day operations of the ballclub as well as player personnel. For the most part, Ryan stayed out of the limelight as well as the general operations.

Like Alva Bradley, Ryan was a native Clevelander, born in the city in June 1904. He graduated from The Ohio State University in Columbus and went into the insurance business after graduation. By the time he became the major partner in the purchase of the Indians from Veeck, his owned one of the more successful insurance companies in the Cleveland area.114

The syndicate Ryan headed, with his 20 percent ownership, did have three partners who would play important roles in the ballclub well past the tenure of Ryan. John Hornbeck, a partner in the Miller and Hornbeck law firm, was strong on legal matters and political connections. George A. Medinger, president of Fostoria Industrial Service, was named a vice president and director of the Indians. He would remain with the club long after Ryan had departed and frequently represented the team at league meetings. He had major authority over radio and television contracts, which would prove to be a significant revenue source. Nate Dolin, manager of the Cleveland Arena box office, would, like Medinger, remain with the club into the next decade. He was placed in charge of the box office and named operations chief, and also approved player salaries and daily promotions.115 His major contribution, however, was the introduction of a new accounting procedure that would have a major impact on the finances of sports franchises. Essentially, Dolin devised a method that enabled a major-league club to depreciate players over a five-year period. The new ownership had to possess 75 percent ownership of the club and assign most of the purchase price to the player contracts. The club also had to reorganize as a completely new business or else the previous book value of the team would be applied. If such a procedure were implemented, the earnings of the team could often actually be reduced to a loss on the books, which could in turn eliminate or at least reduce the need to pay taxes by a franchise.116 The new depreciation procedure would ultimately save numerous sports franchises a considerable amount of money in the future and had immediate benefits to the Indians’ organization.

Ryan did make a contribution during his three years of directing the Indians that turned out to have a major impact on the club’s remaining in Cleveland. Early in his tenure, he negotiated a 25-year deal with the city to lease Municipal Stadium. The city would receive 7 percent of the gate, up from the previous 3 to 5 percent. The club would get 55 percent of the concession sales and would agree to spend $300,000 on improvements. The city would be responsible for the maintenance of the facility while the club would tend to the upkeep of the field. The city agreed to purchase League Park from the club with the intent of tearing down the stands and converting it to a city park. The Indians would continue to have sole control over its radio and television contracts.117 While it did not appear to have much significance at the time to either the club or the city, the long-term lease of the ballpark was likely the decision most responsible for the franchise remaining in Cleveland.

Ryan’s tenure as president was not without controversy. Popular players, including Satchel Paige, were let go before the start of the 1950 season. When the team dropped from third to fourth place in the 1950 season, Lou Boudreau, still very popular as manager, was fired, creating a negative reaction from many fans. While Greenberg was largely responsible for the firing, Ryan supported him on the decision and took much of the heat. The announcement was coupled with the introduction of the new manager, Al Lopez, who had been managing the Indianapolis farm team. Ryan said, “[W]e would not consider replacing Lou Boudreau unless we were able to obtain the services of a man who we felt might do a better job. … That man is Al Lopez.”118 While the firing brought many violently-worded threats from Indians fans, Ryan was to prove prophetic in his statement. In Lopez’s five years with Cleveland, the Indians never finished below second place. No other manager has produced such consistent results for the Indians.

Although the firing of Boudreau was not solely related to the team’s performance, the drop in the standings was coupled with a decrease in attendance of almost 500,000 from 1949. The club was still profitable, reporting a net income of $460,000 after expenses of $3,427,000, including $550,000 of player and coach salaries.119 Obviously unknown at the time, the attendance in 1950 of 1,727,464 fans would actually end up being the largest single-season draw by the franchise until 1993. In all likelihood, the decline in attendance had less to do with the performance of the team than other changes going on in the country, including suburbanization, the increasing use of the automobile, and the rapidly growing prevalence of television as a major entertainment source in the household. The competitive performances of the Indians over the next five years on the field could not offset those societal and demographic trends.

While Ryan noted that the team was profitable, the decline in attendance did have an impact on the club’s overall operations. Initially, Ryan was optimistic about building on the momentum Veeck had created in fortifying the scouting and minor-league affiliations of the franchise. Shortly after the purchase, he declared that the team needed to spend money to make money, including higher salaries and the hiring of 12 new scouts.120 During the 1951 season, he announced the purchase of the Triple-A franchise in Indianapolis, the first such franchise ever owned outright by the Indians. In the aftermath of the 1952 season, however, in which attendance dropped over 250,000 from the previous year, even though the team again finished in second place, Ryan changed direction. The club cut costs, reducing its minor-league affiliates from 13 to 8 and laying off three scouts.121 Ryan and Greenberg had already argued over the acquisition of the Indianapolis franchise, and their dispute grew stronger with these cutbacks. In response to those disagreements, Ryan began to assert even more control over the team, with the intention of firing Greenberg and his $60,000 salary and assuming the general manager duties for himself, just as Veeck had done before him.122

Unfortunately for Ryan, the key members of his board of directors did not support his effort to gain more control of the club. Medinger, Hornbeck, and Dolin led the opposition to Ryan and attempted to gain control of the board by bringing in other investors. Part of their opposition stemmed from not being consulted on the Indianapolis purchase, but their larger concern was the possible removal of Greenberg. None of the three felt Ryan was capable of running the club. Initially when approached by the three, Ryan agreed to sell his stock, but he soon changed his mind and offered to buy out their interests at $500 a share. The three directors rejected his offer and took the issue of control of the organization to the entire board. Ryan lost the battle by a very slim 62-vote margin with all shares of stock cast, and thus agreed to sell his interest in the club at $600 a share. Having bought in at $100 a share in 1949, Ryan netted $200,000 to $250,000 on his initial investment of $55,0000. As 1952 ended, the Indians would again be under new ownership.123 In reality, since Greenberg remained as general manager and Medinger, Hornbeck, and Dolin continued on the board, there would be little noticeable change in how the club was run. If anything, Greenberg was now even more empowered than before.

For the short period in which Ryan was in charge of the Indians, he did have some impact on both the club and on baseball. As the leading partner, he attended all of the owners meetings and was directly involved in the controversy over not renewing the contract of Happy Chandler as commissioner. Initially, Ryan voted against renewing Chandler, then switched his vote in favor, enabling the commissioner to get a 9-to-7 majority of the owners behind him. But Chandler needed support from 12 owners to be retained. Ryan was then named to the search committee for a new commissioner along with Del Webb, Phil Wrigley, and Lou Perini. After some resistance from American League owners, including Ryan, National League President Ford Frick was named the new commissioner.124 While his role in Chandler’s dismissal and Frick’s selection was at best indecisive and vacillating, he had been given a major role of responsibility by the other owners rather quickly during in his short time with the Indians. On the local level, the team reported a profit after each of the three years Ryan was in charge and won over 60 percent of its games, things that would be looked back upon with admiration and envy by later owners. Ryan did not leave the Cleveland sports scene, investing in the Browns after his sale of Indians stock was accomplished. He died in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, in August 1966.

The Baxter Brothers and Myron Wilson, 1953-1956

Myron H. Wilson is often listed as the lead owner of the Indians after Ryan’s interest in the team was bought out. In fact, Wilson owned only 3 percent of the stock in the team and was mostly uninvolved in the club’s operations during his tenure as the titular head. His selection was actually an effort to placate Ryan. While Wilson had voted against Ryan, the two had been and were to remain good friends. Wilson’s title as president was merely a way to keep the peace internally after the deal was consummated.125 Like Ryan, Wilson was a native Clevelander who made his money in the insurance business. Unlike Ryan, he possessed an Ivy League education from Yale.126 The primary owners of the team were actually the Baxter brothers, Charles “Wing” and Andy, who had made their fortune in investment banking. Little is known about them although it is clear their interests remained on the investment side as neither took any kind of a role in managing the club.127 They may have viewed the Indians as a short-term investment since they sold most of their stock less than three years later. The major players on the board remained Medinger, Hornbeck, and Dolin, but in reality the Indians were largely directed by Hank Greenberg, who had even more control in running the club than he had before.