✩ 1972 ✩

Flood v. Kuhn

Introduction

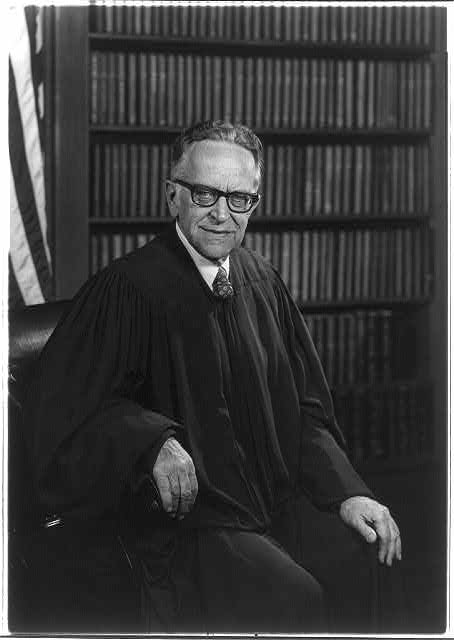

By designating Organized Baseball as an intrastate, rather than interstate, activity, the 1922 Supreme Court decision in Federal Baseball granted the major leagues an exemption from federal antitrust laws. Since 1895, state and federal courts had been protecting the nation’s monopolies in most other industries (sugar, railroads, etc.) In 1937, however, when the Supreme Court signaled it would no longer undermine Congressional legislation, baseball’s antitrust exemption was thrown into question.

From the ballplayers’ perspective, the exemption’s most serious injustice was the reserve clause. Just as ballplayers in the National and American Leagues jumped to the Federal League in 1914-1915 to escape that clause — which bound them to their teams and suppressed their wages — others jumped in 1946 to the Mexican League. To deter or punish jumpers, Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler imposed a blacklist, banning them from rejoining Major League Baseball (MLB) for five years.

The first to jump was Giants outfielder Danny Gardella. After playing the 1946 season for the Veracruz Blues, Gardella was blocked from returning to play in MLB. He sued, claiming in Gardella v. Chandler that club owners were operating in interstate commerce, and were colluding and restraining trade in violation of the antitrust laws. In a federal Court of Appeals in 1949, two of America’s most eminent judges, Jerome Frank and Learned Hand, condemned MLB labor practices. Sensing its vulnerability if the case reached the Supreme Court, MLB settled with Gardella, thus ending the threat.

Besides the Supreme Court, MLB’s antitrust exemption could also be jeopardized by Congressional legislation. Despite MLB lobbying against such investigations, New York Rep. Emanuel Celler launched a Congressional inquiry in 1951. Rather than a threat, however, it allowed repeated testimony — even from some ill-informed players — attesting to the necessity of the reserve clause. MLB’s failure to expand to more US cities received greater scrutiny, but ultimately the Committee refused to revoke baseball’s antitrust exemption.

In 1953, MLB’s reserve clause and antitrust exemption were threatened again in Toolson v. New York Yankees. In 1949, George Earl Toolson was pitching for Triple-A Newark. When the Yankees dropped their affiliation with the team, he was reassigned to Single-A Binghamton, well below his talents. When Toolson refused to report and instead sought a position with a Triple-A Pacific Coast League team, he was blocked, blacklisted, and made ineligible. Toolson sued MLB, claiming it restrained trade in violation of antitrust laws by limiting player movement to other teams. In Federal Baseball the Supreme Court shielded MLB by its narrow definition of interstate commerce, and in Toolson it refused to overrule precedent, claiming Congress had never intended antitrust to cover baseball.

In 1957, Toolson was reaffirmed in Radovich v. National Football League. While the Supreme Court refused to extend an antitrust exemption to professional football, it reasserted baseball’s special status. The Court claimed that overruling Federal Baseball would do more harm than good — siding with the owners rather than the ballplayers.

Other challenges to the MLB exemption emerged in the late 1950s, but they focused on business rather than labor. They were derailed when MLB added four more cities and teams in 1961 and 1962. No further Congressional challenge to baseball’s exemption emerged through the late 1960s.

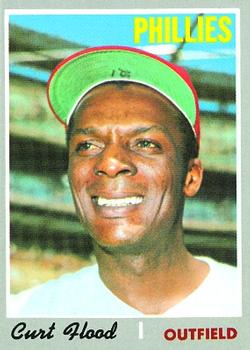

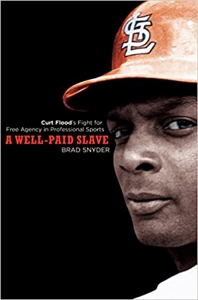

In 1969, however, when Curt Flood was traded without his permission from the St. Louis Cardinals to the Philadelphia Phillies, he refused to report. Playing a dozen years for the Cardinals, Flood had been a three-time All Star, seven-time Gold Glove winner, and perennial .300 hitter, for which he earned an impressive salary. But under the reserve clause, he could be bought and sold. While he might have been (in Flood’s own words) a “well-paid slave,” he was still a slave. He sued MLB, but in Flood v. Kuhn in 1972, the Supreme Court again reaffirmed both Federal Baseball and Toolson. The Court acknowledged the ways baseball operated in interstate commerce, but claimed only Congress could rescind MLB’s antitrust exemption.

While Flood lost, his self-sacrificing initiative inspired other ballplayers, and led by player’s union president Marvin Miller, the reserve clause — which Flood sacrificed his career to challenge — was finally broken via contract law by the Seitz arbitration decision in 1975, and free agency finally emerged in baseball and then all other professional sports.

— Robert Elias

Listen: Curt Flood’s full SABR Oral History Collection interview from August 9, 1992

Curt Flood’s career statistics

| Year | Age | Tm | G | R | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | BA | OBP | SLG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1956 | 18 | CIN | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | .000 | .000 | .000 |

| 1957 | 19 | CIN | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | .333 | .333 | 1.333 |

| 1958 | 20 | STL | 121 | 50 | 17 | 2 | 10 | 41 | 2 | .261 | .317 | .382 |

| 1959 | 21 | STL | 121 | 24 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 26 | 2 | .255 | .305 | .418 |

| 1960 | 22 | STL | 140 | 37 | 20 | 1 | 8 | 38 | 0 | .237 | .303 | .354 |

| 1961 | 23 | STL | 132 | 53 | 15 | 5 | 2 | 21 | 6 | .322 | .391 | .415 |

| 1962 | 24 | STL | 151 | 99 | 30 | 5 | 12 | 70 | 8 | .296 | .346 | .416 |

| 1963 | 25 | STL | 158 | 112 | 34 | 9 | 5 | 63 | 17 | .302 | .345 | .403 |

| 1964 | 26 | STL | 162 | 97 | 25 | 3 | 5 | 46 | 8 | .311 | .356 | .378 |

| 1965 | 27 | STL | 156 | 90 | 30 | 3 | 11 | 83 | 9 | .310 | .366 | .421 |

| 1966 | 28 | STL | 160 | 64 | 21 | 5 | 10 | 78 | 14 | .267 | .298 | .364 |

| 1967 | 29 | STL | 134 | 68 | 24 | 1 | 5 | 50 | 2 | .335 | .378 | .414 |

| 1968 | 30 | STL | 150 | 71 | 17 | 4 | 5 | 60 | 11 | .301 | .339 | .366 |

| 1969 | 31 | STL | 153 | 80 | 31 | 3 | 4 | 57 | 9 | .285 | .344 | .366 |

| 1971 | 33 | WSA | 13 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | .200 | .300 | .200 |

| CAREER | 1759 | 851 | 271 | 44 | 85 | 636 | 88 | .293 | .342 | .389 |

A Life in Baseball

Born in 1938, Curt Flood grew up primarily in Oakland, California, where he was a pupil under the tutelage of legendary coach George Powles, who also helped train future big-leaguers Frank Robinson, Vada Pinson, and Joe Morgan. After Flood graduated from high school in 1956, he signed a contract with the Cincinnati Redlegs for $4,000.

Flood endured segregated living quarters, hostile fans, and discrimination during his first spring training and in his first minor-league stop in the Deep South, but the 18-year-old phenom led the Class B Carolina League with a .340 average and 133 RBIs, and he was called up to make his major-league debut as a pinch-runner on September 9, 1956.

Traded to the St. Louis Cardinals in 1958, Flood blossomed into a star center fielder, winning the first of seven Gold Glove Awards in 1963 and helping the Redbirds win a World Series championship one year later. He and the Cardinals won another World Series title in 1967 and a National League pennant in ’68 — when he appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated with the caption, “Baseball’s Best Center Fielder.”

- Read more: Curt Flood’s SABR biography, by Terry Sloope

- Read more: “Curt Flood’s Baseball Cards,” by John Racanelli and Nick Vossbrink

The Trade

On October 8, 1969, a sportswriter phoned Curt Flood to break the news that his employer for twelve seasons, the St. Louis Cardinals, had assigned his contract to the Philadelphia Phillies as part of a seven-player trade. He had no notice that the Cardinals planned a trade and no desire to go to Philadelphia.

Like every major league contract for more than 80 years, Flood’s contract contained provisions that he, like the other players, believed bound him to his team for the rest of his playing days. He could not escape the contract except by retiring, nor could he prevent his team from selling or trading him. This was known as the reserve system.

Rather than retire, Flood decided to challenge this system. On December 13, 1969, Flood went to the MLB Players Association’s executive committee meeting in Puerto Rico to discuss suing major league baseball in a challenge to the reserve clause. Afterward, the MLBPA executive committee voted unanimously to back Flood — including paying his legal expenses — and Flood filed his lawsuit against major league baseball, seeking to be declared a free agent.

- Read more: “Curt Flood’s 1969 Trade to the Philadelphia Phillies,” by Alan B. Cohen

- Read more: “Flood v. Kuhn: A Summary,” by Mike McCullough