✩ 2022 ✩

Legacy of the Antitrust Exemption

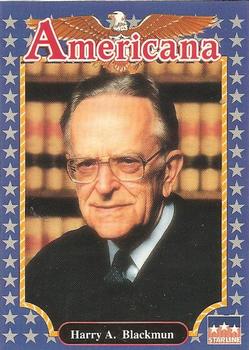

One hundred years ago, the United States Supreme Court’s decision in Federal Baseball Club v. National League on May 29, 1922, was the last gasp for the short-lived Federal League — which challenged the National League and American League as a self-appointed third “major league” — and a lasting gift to Major League Baseball into the twenty-first century.

This ruling granted Major League Baseball exemption from the antitrust laws of the United States, effectively making MLB a legal monopolist and monopsonist.

A monopsonist is a firm that acts as the only purchaser in a market – the opposite of a monopoly, in which a market has only one producer of the product. MLB is the only professional sports league in North America that continues to hold blanket immunity, although others enjoy limited immunity in regard to television rights.1

The Supreme Court building in Washington, DC. (Photo: Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States)

Since 1922, MLB’s antitrust exemption has been upheld in Toolson v. New York Yankees, Inc. (1953) and Flood v. Kuhn (1972). In 1998 Congress passed the Curt Flood Act, which eliminated MLB’s antitrust exemption for labor relations with players.2 The act had little noticeable impact, as Marvin Miller and the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) had already dramatically changed the balance of power in labor relations.

The 1922 Supreme Court decision did not change the behavior of the owners, who already behaved like monopolists. But it did embolden their anti-competitive behavior. The most famous example of this was the reserve clause, which had been in place since 1879.

The half-century following Federal Baseball Club v National League saw the players organize, hire Marvin Miller, and grow into a powerful union. Until 1975, when arbitrator Peter Seitz — who held that role thanks to collective bargaining between the players and owners — ruled that the reserve clause was not infinitely renewable, MLB was granted free reign to impose whatever conditions they wanted in their contracts. The effect, unsurprisingly, was players who were paid far less than what they would have earned on the open market.3

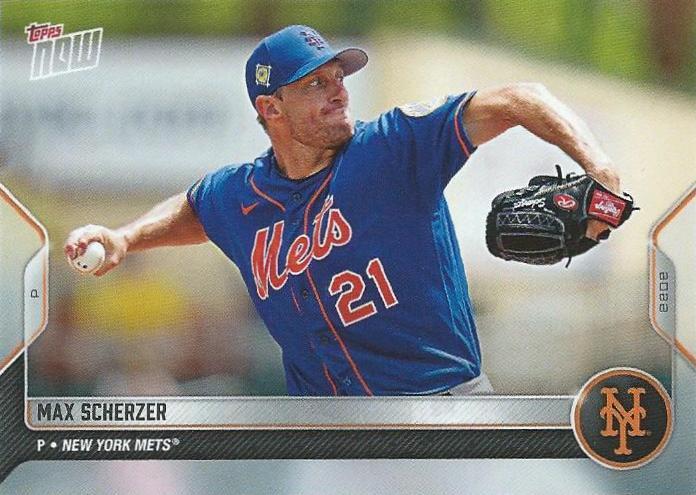

Max Scherzer was one of the top free agents available before the 2022 season. The 37-year-old pitcher signed a record-setting three-year, $130 million contract with the New York Mets. (Photo: Trading Card Database)

Despite the increased bargaining power made possible by the player’s union, players are still not entirely free to pick and choose their terms of employment today.

Collective bargaining has resulted in free agency, but only after six years for most players. In addition, players are still subject to an amateur draft, which limits their choice of initial employer. The inequity of this pay gap between younger and older players was one of the hot-button issues in baseball’s labor dispute during the 2021-22 offseason.

While free agency is the most famous result of MLB’s legal monopoly status, it is not the only one. Because it is exempt from antitrust laws, MLB is able to write contracts and enforce agreements that make it virtually impossible for a competitor league to exist. MLB can threaten to blackball broadcasters who contract with competing baseball leagues, and they can prevent municipally owned stadiums from leasing their MLB-occupied ballparks to competitors, even during off days and the off-season. These tactics would not be possible in a truly competitive market.

The National Football League provides an example of what kind of competition baseball may have faced had the Supreme Court ruled differently in any one of its three baseball cases.

Since 1922, the NFL has had to face off against no fewer than 14 competing leagues.4 In 1986, the United States Football League even successfully sued the NFL for monopolistic practices. MLB’s antitrust exemption has made it virtually impossible for another league to compete. There has been no serious attempt since the demise of the Federal League in 1915. But if the exemption were revoked, we could see more expansion as a way to fend off competition.

Principal Park in Des Moines, Iowa, home of the Iowa Cubs. The minor leagues were drastically altered in 2020, when Major League Baseball eliminated 42 minor league teams, reducing the number of affiliated clubs by 26% overnight. (Photo: Scott Sailor)

What would happen if Congress or the Supreme Court were to strip MLB of its monopoly privilege?

Some argue that revoking MLB’s antitrust exemption would prohibit it from supporting farm systems and could lead to the collapse of the minor leagues.5 This seems unlikely, however.

At the start of the 2022 season, there were 69 professional baseball teams in seven leagues that are not affiliated with MLB. History also suggests that farm systems, while efficient, are not necessary for the provision of future talent. Prior to the rise of the farm system, which MLB originally fought, there were hundreds of independent minor league teams that served as a training ground for future MLB talent.

In December 2020, MLB axed 42 minor league teams, reducing the number of affiliated clubs by 26% overnight. And while the long-term implications of that move are still unknown, the immediate impact was little noticed beyond the affected communities. This diminution of the minor leagues took place despite (or because of?) MLB’s antitrust exemption.

Without its antitrust exemption, MLB could not enforce geographic exclusivity for teams, nor prevent them from moving without league permission. Contrast that with the NFL, which saw the Raiders move from Oakland to Los Angeles, and then back again, despite the league’s protestations. And that was only the beginning of teams that unilaterally decided there were greener pastures in other cities.

Antitrust exemptions allow sports leagues to package broadcasting rights, implement blackouts, and share broadcast revenues in order to shore up weak (i.e. small market) teams. This makes it more difficult for competing leagues to move into markets or secure television contracts of their own.

If MLB was not a legal monopoly, it could not impose standard pay on minor leaguers across all teams and levels, nor would the league be able to impose a limit on the number of minor league franchises with which an MLB team affiliates, or the number of players it employs.

Antitrust exemption paves the way for MLB to bundle the licensing of all team memorabilia into exclusive contracts and strike league-wide sponsorship deals. Without such protection, potential vendors would have 30 different MLB teams with which to negotiate, instead of the MLB monopoly.

Exemption from antitrust laws reaches far more areas of the baseball business than just player contracts. So while players have largely unfettered themselves from the reserve clause chains, MLB still profits handsomely from its status as a legal monopoly. In no small part, it helps explain why the value of its franchises collectively tops an estimated $60 billion.6

Sports leagues argue that they cannot exist without restricting competition among their members. While there is some truth to that, it is also a convenient reality that being a monopolist is quite profitable.

— Michael Haupert

Sources and Notes

Sources

Farzin, Leah, “On the Antitrust Exemption for Professional Sports in the United States and Europe,” Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal, Vol. 22, No. 75, 2015.

Grow, Nathaniel, “In Defense of Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption,” American Business Law Journal, Vol. 49, No. 2, Summer 2012: 211-273.

Haupert, Michael, “Pay, Performance, and Race During the Integration Era,” Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1, Spring 2009a: 37-51.

Haupert, Michael, “Player Pay and Productivity in the Reserve Clause and Collusion Eras,” Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Social Policy Perspectives, Fall 2009b: 63-85.

Ozanian, Mike, and Justin Teitelbaum, “Baseball’s Most Valuable Teams 2022: Yankees Hit $6 Billion As New CBA Creates New Revenue Streams,” Forbes Magazine, March 24, 2022.

Scully, Gerald W., “Pay and Performance in Major League Baseball,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 64, No. 6, December 1974: 915-30.

Scully, Gerald W., The Business of Major League Baseball (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989).

Zimbalist, Andrew, “Salaries and Performance: Beyond the Scully Model,” in Diamonds Are Forever: The Business of Baseball, ed. Paul M. Sommers, ed. (Washington, DC: Brookings, 199a2: 109-33).

Zimbalist, Andrew, Baseball and Billions: A Probing Look Inside The Big Business Of Our National Pastime (New York: Basic Books, 1992b.

Notes

1 For an overview of professional sports and antitrust legislation, see Farzin (2015).

2 This applied only to players, and not any other labor groups, such as umpires.

3 This has been demonstrated in numerous studies. See, for example, Haupert (2009a, 2009b), Scully (1974, 1989), and Zimbalist (1992a, 1992b)

4 The competitors: the AAFC, APFA, WFL, USFL, UFL, Alliance of American Football, two different versions each of the XFL and arena football leagues, and three different versions of the AFL before merging with a fourth in 1966.

5 Grow (2012).

6 Ozanian and Teitelbaum (2022).